Identification and Treatment of Substance Misuse on an Inpatient Psychiatry Unit

Abstract

This chart review study examined identification and treatment of substance misuse on an inpatient psychiatry ward before and after the hospital's administration made changes to increase attention to patients' substance misuse. Before the ward changes, 113 of 250 inpatients (45 percent) were identified as misusing substances. Misusers were significantly more likely to be younger, male, single, and cigarette smokers. After the ward changes, substance misuse was more than twice as likely to be addressed in treatment planning and discharge diagnoses, and referrals to substance abuse treatment were nearly twice as likely to be made. Changes in assessment of and treatment planning for psychiatric inpatients may increase attention to substance misuse.

The misuse of alcohol and drugs is prevalent among people with mental illnesses and is associated with poor prognosis (1). Coordination in the treatment of mental illness and substance misuse is recommended (2). The American Psychiatric Association's (APA) treatment guidelines for substance use disorders address comprehensive assessment, intoxication and withdrawal prophylaxis, and development and implementation of an overall treatment strategy including appropriate referrals (3). National data, however, indicate that few patients receive adequate treatment (4). In the Healthcare for Communities Survey only 8 percent of individuals with co-occurring disorders received treatment for both disorders in the previous 12 months, and 72 percent did not receive any treatment at all. When treatment was received, most often it was for the mental disorder alone (23 percent).

Individuals with co-occurring disorders often require high-cost services such as inpatient and emergency care, yet little is known about addictions treatment services in these acute settings (5). A study conducted at a Department of Veterans Affairs hospital and a state hospital revealed underdiagnosis of substance use disorders and low rates of treatment planning and referrals for inpatients who met research criteria for schizophrenia and a substance use disorder (6).

This study used a naturalistic design to examine the identification and treatment of substance misuse in a teaching hospital with a general psychiatric inpatient sample. In 2002 the hospital administration implemented changes in ward procedures to improve diagnosis and treatment of substance misuse as recommended in the APA's treatment guidelines for substance use disorders (3). The retrospective study reported here used chart review to examine clinical services before and after the ward changes were made.

Methods

The study was conducted at a 22-bed adult inpatient psychiatric service in a teaching hospital in northern California, where patient evaluation, treatment planning, and service delivery are conducted by multidisciplinary teams. Data for this study were collected by chart review. Before the hospital implemented changes in ward management in 2002, the charts of 250 patients hospitalized from 1998 to 2001 were randomly selected, and the most recent hospitalization was reviewed. The sample was representative of the larger patient population and was described previously (7).

Systematic chart review gathered data on admission date, commitment status, demographic characteristics, substance use, and DSM-IV discharge diagnoses. Alcohol abuse and illicit drug use were assessed on intake and charted by the clinician as current, former, or never. Urine drug screens used standard immunoassays and cutoff concentrations. For the purposes of this report, substance misuse was defined as current alcohol abuse or any current illicit drug use, based on evidence that people with severe mental illness may be vulnerable to adverse effects from even low levels of drug use (1,5). The definition was anticipated to capture a wide range of substance use patterns, including substance abuse and dependence, and was based on the way in which the information was charted by the clinical team. Charts of patients with identified substance misuse were further reviewed for inclusion of alcohol or drug use in the master treatment plan, referral to dual diagnosis groups on the unit, prescription of medications to treat intoxication or withdrawal, discharge diagnosis of DSM-IV substance abuse or dependence, clinician advice to abstain from drugs or alcohol, and discharge referrals for addictions treatment.

Two years later, a second chart review was conducted after changes in management on the ward. The changes included new clinical leadership, the adoption of a more detailed addiction assessment specifying different classes of drugs as well as use history, and the adoption of a separate treatment planning protocol for substance misuse. By using the same data collection procedures, charts were reviewed for patients consecutively admitted to the unit, and 78 patients with substance misuse were obtained. (The 78 patients were a subsample of cigarette smokers recruited from the unit as part of another study.)

The study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco institutional review board. Data were anticipated to be fairly complete given that medical records staff audited approximately 93 percent of the inpatient charts. For both chart reviews, the first ten charts were double-coded to ensure adherence to the coding system. Interrater reliability was assessed with 10 percent of charts. Overall agreement and substance misuse classification were 96 percent at both time points.

Results

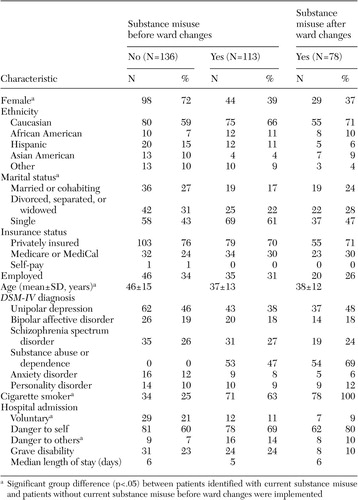

Before the hospital implemented the ward changes, of the 250 charts reviewed, 113 (45 percent) had current substance misuse identified: 66 patients (27 percent) with alcohol abuse and 92 patients (37 percent) with illicit drug use. Forty-five patients (18 percent) misused both alcohol and drugs. Drugs used included marijuana by 47 patients (19 percent), stimulants by 41 (16 percent), opioids by 18 (7 percent), and other by 25 (10 percent). Urine drug tests were ordered for 152 patients (61 percent). One chart lacked substance use information and was dropped from further analysis. Of the 136 patients not currently misusing substances, 28 patients (21 percent) formerly abused alcohol and 36 patients (26 percent) formerly used illicit drugs. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients with current substance misuse were significantly more likely to be younger, never married, male, cigarette smokers, and hospitalized involuntarily, often for danger to others.

Of the 113 patients currently misusing substances, fewer than half had substance use identified in treatment planning (49 patients, or 43 percent) or discharge diagnoses (53 patients, or 47 percent), were advised to abstain from drugs or alcohol (42, or 37 percent), or were referred for addictions treatment (46, or 41 percent). Although therapy groups were held four times daily, specific dual diagnosis groups, which addressed substance misuse, were held infrequently; such groups were offered to only 37 patients (33 percent), of which 19 patients (17 percent) attended. Withdrawal prophylaxis was provided to ten of 21 patients (48 percent) with alcohol abuse or dependence and to three of 18 patients (17 percent) misusing opiates.

The second chart review two years later examined the records of 78 patients who were identified with substance misuse (Table 1). Analyses indicated significant improvements in treatment planning (odds ratio [OR]=2.3, p<.01), in discharge diagnoses (OR=2.5, p<.01), and with referrals to addictions treatment (OR=1.8, p=.05). A majority of patients had substance misuse attended to in treatment planning (50 patients, or 64 percent), discharge diagnoses (54 patients, or 69 percent), and treatment referrals (43 patients, or 55 percent). Clinical advice to abstain from drugs and alcohol improved, but not significantly. Seventeen patients (22 percent) received all four of these treatment components. Inclusion of substance misuse in the treatment plan was associated with greater odds of diagnosing substance use disorders (OR=4.0, p<.01) and providing referrals for addictions treatment (OR=3.5, p<.01).

Discussion and conclusions

This naturalistic study examined clinical attention to substance misuse on an inpatient psychiatry unit before and after changes in ward management. The changes included new clinical leadership, the adoption of a more detailed addiction assessment specifying different classes of drugs as well as use history, and the adoption of a separate treatment planning protocol for substance misuse. A chart review by independent investigators indicated that before the hospital implemented changes, 45 percent of the general psychiatric inpatient sample misused substances. Although this estimate is high, it may still underestimate the proportion of patients with current substance misuse. In a study of patients in the public mental health system, 60 percent met criteria for comorbidity based on research diagnostic interviews (8). Substance misuse in inpatient psychiatry needs to be the expectation, not the exception, and mental health treatment providers need to be prepared to deliver appropriate services (2).

Before ward changes were made, fewer than half of patients identified with substance misuse had it addressed in treatment planning, discharge diagnoses, or treatment referrals. Dual diagnosis groups met for one hour weekly. During the chart review it was noted that the group was often held on Sunday, one of the lowest census days, and attendance required a physician referral. Consequently, only 17 percent of patients who misused substances attended a dual diagnosis group during their stay.

After ward changes were made, the identification of substance misuse on the treatment plan and as a discharge diagnosis improved significantly. Referrals to addictions treatment also increased. Although a majority of patients received clinical attention to their substance misuse, a sizeable minority remained untreated, and improvement in clinician advice to abstain from drugs and alcohol was not significant.

Limitations of this study included restriction to one clinical site and reliance on chart documentation, which may underestimate actual practice. Assessment of substance misuse likely varied by clinician, and details on substance misuse were limited. Generalizability of the findings beyond the study site is unknown; however, the site is a nationally recognized psychiatric hospital and teaching center, and the findings are comparable to those in previous reports from Veteran Affairs and state hospital psychiatric units (6).

Attention to patients' misuse of addictive substances is critical for informing appropriate psychiatric diagnoses, pharmacologic regimens, and treatment referrals and for reducing the risks for rehospitalization, suicidality, and acts of violence (5,9). The findings reported here suggest that changes in assessment and treatment planning methods may provide a simple intervention for increasing clinical attention to patients' misuse of addictive substances. Inclusion of substance misuse in the treatment plan is a relatively simple intervention for raising staff awareness and attention to addictive substances in clinical care. Similarly, discharge diagnoses serve to communicate treatment needs to referral clinicians. Additional quality assurance strategies may include in-service staff training, chart prompts and ongoing chart monitoring, greater availability of dual diagnosis groups during hospitalization, and greater coordination with referrals for addictions treatment (10). Comprehensive integrated services for individuals with co-occurring disorders are emerging as an evidence-based practice (2). Self-study evaluations can help elucidate the extent to which these integrated services are put into clinical practice.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, 401 Parnassus Avenue, TRC 0984, San Francisco, California 94143-0984 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of two samples of psychiatric inpatients whose charts were reviewed before and after the hospital made changes to a psychiatric ward to increase attention to substance misuse, by whether they currently misused substances

1. Miles H, Johnson S, Amponsah-Afuwape S, et al: Characteristics of subgroups of individuals with psychotic illness and a comorbid substance use disorder. Psychiatric Services 54:554–561, 2003Link, Google Scholar

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Report to Congress on the Prevention and Treatment of Co-Occurring Substance Abuse Disorders and Mental Disorders. Washington, DC, US Dept. of Health and Human Services, 2002Google Scholar

3. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders: alcohol, cocaine, opioids. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1–59, 1995Link, Google Scholar

4. Watkins KE, Burnam A, Kung FY, et al: A national survey of care for persons with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 52:1062–1068, 2001Link, Google Scholar

5. RachBeisel J, Scott J, Dixon L: Co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: a review of recent research. Psychiatric Services 50:1427–1434, 1999Link, Google Scholar

6. Kirchner JE, Owen RR, Nordquist C, et al: Diagnosis and management of substance use disorders among inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 49:82–85, 1998Link, Google Scholar

7. Prochaska JJ, Gill P, Hall SM: Treatment of tobacco use in an inpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiatric Services 55:1265–1270, 2004Link, Google Scholar

8. Havassy BE, Alvidrez J, Owen KK: Comparisons of patients with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders: implications for treatment and service delivery. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:139–145, 2004Link, Google Scholar

9. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Clark RE, et al: The course, treatment, and outcome of substance disorder in persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:42–51, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, et al: Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:469–476, 2001Link, Google Scholar