Brief Reports: Impact of the Wait for an Initial Appointment on the Rate of Kept Appointments at a Mental Health Center

Abstract

Failure to keep initial appointments at a community mental health center results in a burden on the staff and the center's financial resources. The authors studied referrals to an outpatient program and found that delay in scheduling appointments had a significant impact on rate of kept appointments. The impact was significant during the first week of delay and appeared to stabilize after day seven. Age influenced the rate but differed in influence between the adult and child programs. Changes aimed at reducing wait time for initial appointments may favorably affect rate of kept appointments and ultimately preserve staff and financial resources.

In an era of budget constraints, community mental health centers strive to increase their proficiency to provide services that are both cost-effective and of high quality. In particular, the problem of missed initial appointments continues to have a significant impact on these programs and challenges fiscal and staff resources.

Many studies have attempted to explain the phenomenon of missed appointments to remedy this problem. In 1980, Hochstadt and Trybula (1) commented on the relevance of research to reduce missed appointments and help preserve the resources of the centers. Studies have examined patient characteristics, including demographic and diagnostic variables (2,3,4), as well as administrative and procedural issues (5,6,7,8), with the hope of improving attendance at the first appointment. Strategies have included using telephone and letter prompts before the first visit (9), having mental health staff establish contact with patients before the scheduled appointment (10), and other interventions to improve compliance with the initial visit.

Although there are some similarities in the findings and recommendations from these studies, there are differences in results with regard to patient characteristics and clinic administrative issues that require more work and clarification. In particular, a procedural issue that needs further study is the impact of the time until an appointment, or appointment delay, on the rate of kept appointments. Disparate results from earlier studies (5,8) and our impression that this was a significant factor that led to missed initial appointments in our clinic led to the study reported here. Because many of the previous studies used data from small samples of patients over a short referral period, we sought to study a large sample of referred patients over a five-year period. In addition, some patient characteristics appeared to influence the rate of kept appointments for the first appointment, and we attempted to identify these patient characteristics in this large sample of referrals.

Methods

The sample consisted of 5,901 consecutive patients who were referred or sought out an initial appointment in the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center community psychiatry adult or child and adolescent outpatient programs between January 2, 1995, and October 18, 2000. A total of 3,137, or 53 percent, of the patients were males, and 2,764, or 47 percent, were females. A total of 4,247, or 72 percent, of the patients were in the adult program, and 1,629, or 28 percent, were in the child and adolescent program. The age range of the adult patients was 19 to 94 years; patients in the child and adolescent program were less than 19 years old.

The community psychiatry program is a public mental health clinic operating on the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center campus in Baltimore. An intake specialist fields telephone calls from the referral line and gathers information on the patient's chief complaints, insurance status, and other demographic information. The intake specialist is a nonclinician who is supervised by the administrative staff. If the patient is appropriate for an outpatient program, an appointment is given, and the patient is informed about how long the evaluation process is expected to take. A letter is sent to the patient, and a reminder phone call is made one day before the appointment.

The outcome of interest was whether the patient missed the appointment because of a cancellation or because he or she simply failed to show up. The major predictor of interest was appointment delay or the number of days between the initial contact and the appointment. Age, sex, and program (child and adolescent or adult) were considered potential confounding variables. The chi square test for trend was used to assess the univariate relationship between appointment delay and missed appointment. The chi square test or Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to evaluate univariate relationships between the potential confounders and appointment delay or missed appointment. Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate the magnitude of the relationships between the predictors and missed appointments, with control for the other variables in the model; an age-by-program interaction term was included in the model.

Results

The delay between initial contact and the scheduled appointment ranged from 0 to 47 days (mean=4.3±4.2 days). The appointment delay was greater, on average, for males (mean=4.6±4.5 days; range, 0 to 40) than for females (mean=4±3.9 days; range, 0 to 47) (t=4.9, df=5,886, p<.001). The appointment delay was greater for patients in the child and adolescent program (mean=6.2±5.7; range, 0 to 47) than in the adult program (mean=3.5±3.2; range, 0 to 28) (t=23.0, df, 5,893, p<.001). Age was inversely related to appointment delay (Pearson's r=-.20, p<.001).

Of the 5,901 patients scheduled for an appointment, 1,829 (31 percent) cancelled or did not show. The rate of cancellations and no-shows was slightly but significantly higher for males than for females (1,004 patients, or 32 percent, and 802 patients, or 29 percent, respectively; χ2=4.03, df=1, p=.045) and for patients in the adult program than for those in the child and adolescent program (1,359, or 32 percent, and 456, or 28 percent; χ2= 5.80, df=1, p=.02).

A strong linear relationship was found between appointment delay and cancellations and no-shows (χ2 [trend]=95.4, df=1, p<.001). The rate of cancellations and no-shows was 12 percent (20 patients) for the 173 patients who were given an appointment the same day as the initial contact but 23 percent (311 patients) for the 1,376 patients who were given an appointment the day after the initial contact. The rate rose to 42 percent (100 patients) among the 241 patients whose appointment was delayed for seven days and reached a maximum of 44 percent (18 patients) among the 41 patients for whom the delay was 13 days.

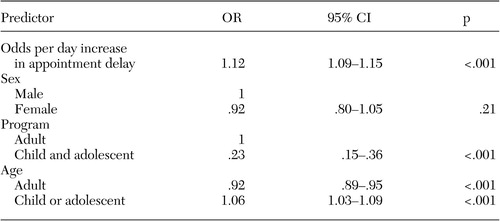

Table 1 shows the results of the multivariate logistic regression model predicting cancellations and no-shows. The odds of cancellations or no-shows increased by 12 percent for every day of delay between the initial contact and the appointment, with control for the other variables in the model. Patients in the child program were about one-fourth as likely as those in the adult program to miss an appointment. The relationship between age and cancellations and no-shows was significantly different for patients in the different programs. The model predicted that for the patients in the adult program, the odds of missing the appointment decreased by 8 percent with each year of increase in age. In contrast, for patients in the child program, the odds of missing the appointment increased by 6 percent with each year of increase in age (interaction term, beta=.07, p<.001).

Discussion and conclusions

Our findings, based on a large sample of patients consecutively referred for treatment over an extended five-year period, support our impression that increased wait time for an initial appointment for services at a community mental health center will adversely affect the rate of kept appointments. More important, the rate of kept appointments will be affected most significantly with each day of delay during the first week until the scheduled appointment. These results suggest that clients who are able to quickly obtain psychiatric services will more likely appear for their initial appointment, and the failure to keep the intake appointment will increase linearly with each day of appointment delay. Consequently, the centers might benefit from efforts that attempt to provide clients with a first appointment closer to the time of referral. Because the rate of kept appointments for initial appointments tended to stabilize after the first week, interventions after this period are less likely to improve the rate of kept appointments. Centralizing the intake process and using a dedicated staff to accept referrals and accommodate more timely appointments for the initial intake may help reduce the rate of no-shows and cancellations.

The other findings from the study suggest that some client characteristics influence whether someone keeps an initial appointment for psychiatric treatment and that these characteristics may differ across adult and child and adolescent programs. More specifically, age affects the rates of no shows and cancellations differently in our two programs. Younger children in the child program and older adults in the adult program have better rates for kept appointments. One reason might be that care providers may ensure that clients arrive at the first appointment by accompanying them to the clinic. Because older children, or adolescents, and younger adults are more likely to arrive alone for their appointments, they may lack the support of an interested companion, spouse, or care provider who might encourage their attendance for the initial evaluation and treatment. To improve the rate of kept appointments, during the referral process the intake specialist might suggest that the client use the support of other concerned individuals to help him or her get to the initial appointment, if possible.

Although age and sex were variables we looked at as predictors of the rate of kept appointments, we did not use or did not have access to a variety of demographic and diagnostic variables that could have influenced our outcome of interest. A more rigorous analysis that included some of those variables would perhaps provide a better assessment of the problem of no-shows and cancellation of initial appointments for psychiatric treatment at community mental health centers. In addition, the centers with longer wait times to initial appointments might experience different rates of kept appointments for first appointments than the initial rate of kept appointments in our center. Although we were unable to differentiate no-show patients from patients who cancelled and rescheduled their initial appointments, we recognize that there might be differences between these two groups that would be interesting to assess.

In conclusion, understanding other potential predictors and the important influence related to appointment delay should help improve the rate of kept appointments and ultimately help preserve staff and financial resources for the centers.

Dr. Gallucci, Mr. Swartz, and Ms. Hackerman are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, 4940 Eastern Avenue, D2 East, Baltimore, Maryland 21224 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Multivariate logistic regression model of relationship between selected predictors and appointment cancellations and no-shows for initial appointments at community mental health centers

1. Hochstadt NJ, Trybula J Jr: Reducing missed appointments in a community mental health center. Community Psychology 8:261–265, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hershorn M: The elusive population: characteristics of attenders versus non-attenders for community mental health center intakes. Community Mental Health Journal 29:49–57, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Allan AT: No-shows at a community mental health clinic: a pilot study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 34:40–46, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Otero J, Lugue A, Conde M, Jimenez C, Serrano C: Factors associated to non-attendance to psychiatric first visit. Actas Espanolas de Psiquiatria 29:153–158, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

5. Glyngdal P, Sorensen P, Kistrup K: Non-compliance in community psychiatry: failed appointments in the referral system to psychiatric outpatient treatment. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 56:151–156, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Greeno CG, Anderson CM, Shear MK, Mike G: Initial treatment engagement in a rural community mental health center. Psychiatric Services 50:1634–1636, 1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Kluger MP, Karras A: Strategies for reducing missed initial appointments in a community mental health center. Community Mental Health Journal 19:137–143, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Peeters FP, Bayer H: "No-show" for initial screening at a community mental health centre: rate, reasons, and further help-seeking. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:323–327, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Swenson TR, Pekarik G: Interventions for reducing missed initial appointments at a community mental health center. Community Mental Health Journal 24:205–218, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Stickney SK, Hall RC, Garnder ER: The effect of referral procedures on aftercare compliance. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 31:567–569, 1980Abstract, Google Scholar