Construct Validity of a Measure of Subjective Satisfaction With Life of Adults With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In a multisite study, the authors examined the construct validity and utility of a brief self-report Satisfaction With Life scale, an expanded 21-item version of one of the earliest measures of subjective satisfaction with life used with individuals with serious and persistent mental illness. The Satisfaction With Life scale measures satisfaction in four domains: living situation, social relationships, work, and self and present life. METHODS: Satisfaction With Life scale data were gathered from consumers receiving community treatment at two sites in Los Angeles (N=166 and N=172, respectively) and one in Wisconsin (N=146). A confirmatory factor analysis of a hypothesized four-factor structure using data from the pooled Los Angeles samples revealed that several items were less than optimal indicators of the underlying domain. On the basis of an analysis of each item, the Satisfaction With Life scale was reduced to 18 items, and the factor structure and factor loadings of the revised scale were cross-validated with data from the Wisconsin sample. The 18-item scale was further validated by testing hypotheses regarding the relationship between the instrument's four domains, or subscales, and clinically important life conditions of clients in the areas of symptoms, living and employment situations, and social relationships. RESULTS: The findings provided excellent support for the construct validity of the 18-item Satisfaction With Life scale, which assesses an individual's subjective satisfaction with his or her current life in the four domains: living situation, social relationships, work, and self and present life. CONCLUSIONS: The brief, easily completed 18-item Satisfaction With Life scale is a useful tool in evaluation research for assessing the subjective satisfaction with life of adults with serious mental illness.

Evaluations of clinical and services interventions for persons with serious mental illness ideally include investigation of a broad range of outcomes, such as clinical, functional, quality-of-life, social benefit, and economic outcomes (1). Such evaluations also need to encompass multiple perspectives, such as those of treatment providers, consumers, family members, and society, because mental health interventions typically affect a variety of stakeholders who often have differing interests and needs and who are likely to view or value a treatment program or outcome in different ways (1,2,3). In this regard, a 2001 report of the Institute of Medicine (4) addressed the need to develop more opportunities for the voices of consumers to be heard and for consumers to be full participants in their treatment. Therefore, and consistent with the consumer empowerment and recovery movements, we believe it is imperative to gain the consumer's perspective in outcome measurement (5,6,7).

Although a number of reliable and valid self-report measures of clinical symptoms exist, psychometrically sound measures assessing consumer views of nonclinical dimensions of outcome—which are deemed extremely important by consumers—are less well developed. The term "quality of life" is often used to refer to these nonclinical domains, but unfortunately this phrase is rarely well defined in the mental health field and is inconsistently used. "Quality of life" may be used to refer both to "objective" life conditions—such as current or recent functioning, external living conditions, and access to resources and opportunities in various domains—and to "subjective" indicators of well-being, including current satisfaction with various life domains and with one's overall life (8,9,10).

One of the earliest measures of subjective satisfaction with life of persons with serious and persistent mental illness was developed in 1971 as part of the seminal evaluation of the Training in Community Living model (now called assertive community treatment) as an alternative to the mental hospital (11). Because treatment in the community as an alternative to the hospital represented a dramatic change and because deinstitutionalization efforts often resulted in deplorable community living conditions, we believed it was critical to compare standard hospital treatment with community treatment not only in terms of objective conditions of consumers' lives, but also in terms of individuals' subjective satisfaction with their lives and life conditions. The initial version of the Satisfaction With Life scale (12) drew from innovative work by Fairweather and associates (13), who had developed four Likert-type self-report items to investigate clients' satisfaction with their living conditions, leisure activity, community living, and job. The initial Satisfaction With Life scale consisted of eight items that assessed the client's satisfaction with the "place where you live," the "people with whom you live," "the food you eat," "the recreational facilities in or near the place where you live," the "number of friends you have," "your job situation," "your present life," and the extent to which "you have as much freedom as you want."

In 1978 some of us embarked on a new research project to evaluate the effect of ongoing long-term community treatment of young adults with schizophrenia (14,15). The key goals of treatment were sustained community living as well as improved social and work functioning and quality of life. To measure consumers' subjective satisfaction with their lives, we modified and expanded the original Satisfaction With Life scale to create a 21-item scale that might yield satisfaction ratings for various life domains rather than simply an overall life satisfaction score. Toward this end, we expanded the living situation section to include additional dimensions of quality of residence, such as amount of privacy and space. We added a second item regarding work. We also provided a more thorough assessment of the social relationships and leisure area, because consumers indicated the critical importance of this domain. Finally, we expanded coverage of the individual's personal well-being by including two items that assessed the extent to which one's problems are interfering with life.

The scale is administered during a research staff person's face-to-face follow-along assessment of fully informed, consenting participants. Individuals are presented with a copy of the Satisfaction With Life scale and are read these directions, which are printed at the top of the form: "Below are some questions about how you like your present life. Put an X through the words that best reflect your feelings about your life at this time." Each item is followed by five Likert-type response options. If an individual has difficulty with reading, attention, or concentration, the staff person reads the questions and response options to the participant.

During our research program over the past 25 years, we conducted several (unpublished) small studies to investigate various psychometric properties of both the early eight-item version of the Satisfaction With Life scale and the more recent 21-item version. Favorable results justified our continued use of this measure. Recently a multisite research opportunity enabled a large enough sample for a far more rigorous study of the construct validity of the 21-item scale. In this article, we report the methods and findings of this multisite study of the Satisfaction With Life scale's construct validity. In the discussion section we review and compare more recently developed measures of similar concepts, and we comment on cautions that must be taken in the use of satisfaction-with-life measures. We conclude with comments about anticipated directions in this measurement area.

Methods

Sources of data

Data for the study of the construct validity of the Satisfaction With Life scale came from three existing longitudinal studies investigating different approaches to the community care of adults with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-related disorders. Two studies were conducted in Los Angeles (16), and the other in Dane County, Wisconsin (14,15). In all three studies the Satisfaction With Life scale had been administered in face-to-face interviews with participants at their time of study entry (baseline) and at subsequent six-month intervals.

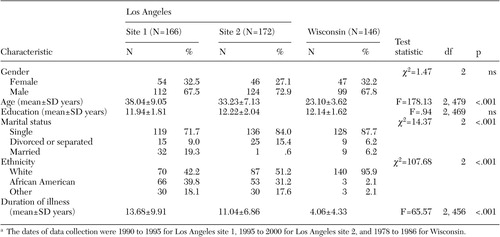

Characteristics of the samples at the time of study entry are summarized in Table 1. The samples were quite similar in gender and education. Because the Wisconsin project focused on young adults relatively early in the course of their disorder, the participants at this site were considerably younger and had shorter durations of illness than those at the Los Angeles sites. Reflecting the ethnic composition of the sites, there was little ethnic diversity among the Wisconsin participants, in contrast to considerable diversity in the Los Angeles samples.

Validation of hypothesized factor structure

As noted above, this 21-item scale represented an expansion of our original eight-item scale in an effort to assess life satisfaction in different domains. We developed our hypothesized conceptual model, or factor structure, on the basis of a review of notes made when the 21-item scale was developed as well as an independent review of the items by the first two authors. We classified each of the items as purportedly tapping "current satisfaction" with life in one of four domains or factors: living situation (five items), social relationships (six items), work (two items), and self and present life (eight items).

Methods to test and validate this hypothesized structure involved several sequential steps. First, we combined the two Los Angeles samples and then used this pooled Los Angeles sample at the baseline, or study entry, period to test the hypothesized four-factor structure, using LISREL 8.53 (17) to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis. Because this analysis indicated a less-than-optimal fit of the hypothesized structure to the data, our second step was to refine the Satisfaction With Life scale. On the basis of an analysis of the factor loadings, the LISREL modification indexes, and a theoretical analysis of the items by the authors, we reduced the number of scale items to 18. Third, we cross-validated the factor structure and factor loadings of the revised Satisfaction With Life scale by using data from the baseline period of the Wisconsin sample. Factorial invariance analysis, based on methods proposed by Joreskog (18), was conducted to cross-validate the Los Angeles factor structure and loadings with data from the Wisconsin sample.

Relationship with life conditions

Having gained confidence in the validity of the theoretical structure of the Satisfaction With Life scale through the steps described above, we then sought to further validate the instrument's subscales by testing a series of hypotheses about the relationship between the subscales and clinically important life conditions of clients. Consistent with the theories of Lehman (8) and others, we hypothesized that subjective satisfaction with life is contributed to by both personal factors, including mental health symptoms, and "objective" life conditions in the relevant domain, such as the client's living and employment situation and quality of social relationships. Meanwhile, Corrigan and Buican (19) and others (20,21) showed that the client's assessment of the subjective quality of his or her life is most strongly influenced by his or her symptoms.

These findings raised the concern that measures of subjective satisfaction or well-being are simply proxy measures for symptom severity. If such measures are to have evaluation utility, we need evidence that they are related to other hypothesized factors, such as objective life conditions, after control for the effects of symptoms. Therefore, the four hypotheses were generated and tested.

First, severity of affective symptoms will be negatively correlated with scores on all the Satisfaction With Life subscales but will have the strongest negative correlation with scores on the self and present life subscale, because affective symptoms are commonly associated with negative self-evaluations.

Second, clients who report having a greater number of symmetrical social relationships will show greater satisfaction with their social relationships and self and present life, compared with clients with fewer symmetrical social relationships, after the effects of affective symptoms are controlled for.

Third, clients living in independent living situations will report greater satisfaction with their living situation than those living in restricted living situations, such as nursing homes, prisons, and hospitals, after the effects of affective symptoms are controlled for.

Fourth, clients working in competitive jobs will report higher levels of work satisfaction than those who are not working, after the effects of affective symptoms are controlled for.

We used data from the Wisconsin sample to test these hypotheses, because the independent research interviewers who administered the Satisfaction With Life scale during face-to-face interviews at the Wisconsin site also collected data with additional measures, including the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (22), and obtained detailed information about clients' current living and employment situations and social relationships. The hypotheses were tested at three time points—at study entry and at 12 and 24 months after entry into the study—to enable examination of the consistency of the predicted relationships.

Results

Validation of hypothesized factor structure

Fit to data from the pooled Los Angeles sample. To evaluate the results of the confirmatory factor analysis that tested the fit of the hypothesized factor structure to the pooled Los Angeles sample data, we used the recommendations of Hu and Bentler (23) and established the following criteria for an acceptable model fit: comparative fit index (CFI) >.95, non-normed fit index (NNFI) >.95, and standardized root mean residual (RMR) <.08. The CFI is analogous to the change in R2 used in multiple regression. In confirmatory factor analysis, it provides an index of the improvement of the overall fit of a hypothesized factor structure, relative to an independence model, which assumes that the variables do not load on any factor and that the factors are uncorrelated. The NNFI is similar to the CFI but includes correction for the number of parameters being estimated—for example, for the number of factor loadings and factor correlations. The standardized RMR indicates the average of the standardized residuals derived from the fitting of the variance-covariance matrix for the hypothesized factor structure to the variance-covariance matrix of the sample data.

The structure provided a reasonably good fit. (A detailed table is available from the first author on request.) All the factor loadings were significant, with t values ranging from 2.28 to 17.31. The CFI was .95, the NNFI was .94, and the standardized RMR was .066. However, two items loading on the self and present life factor had substantially lower loadings (.14 and .13) than did the other items loading on that factor, and the reliabilities of these two items on this factor were unacceptably low (both .02). A possible contributor was that the response categories for these items were substantially different, in a likely confusing way, from the other items of the Satisfaction With Life scale. For these reasons we decided to delete these two items from the scale. The two items were "In all, considering your life situation now, how bothered are you by your problems?" and "How often do your problems prevent you from doing the things that you would like to do?"

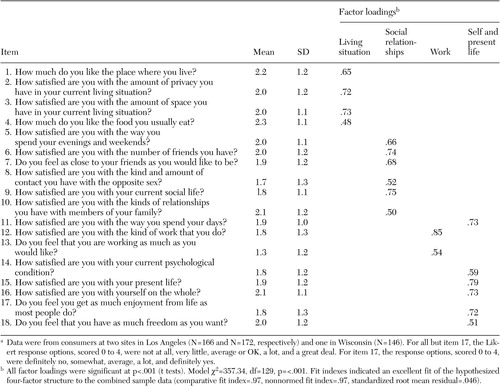

A further concern was that the modification indexes indicated that another item—"How much do you like the leisure time activities and facilities available to you?"—did not clearly load on any one factor. At the time the scale was originally constructed, many adults with serious mental illnesses lived in institutions or large group facilities that included recreational areas, leisure activities, or both. This type of living situation is now more rare. We therefore decided to drop this item from the Satisfaction With Life scale, because its "dated" nature results in its having poor content validity as an indicator of satisfying living arrangements. After these deletions, an 18-item scale resulted. The 18 items are displayed in the left column of Table 2. The Likert options from which the respondent chooses appear in a footnote to the table.

An additional consideration was the possibility of a second-order factor, because the factor analysis of the pooled Los Angeles data resulted in correlations among the first-order factors that ranged from .47 to .82. We thus examined whether adding a higher-order factor would significantly improve the fit of the hypothesized structure to the data. It did not. On the basis of theory as well as parsimony, we therefore chose to cross-validate the first-order structure.

Cross-validation with data from the Wisconsin sample. On the basis of methods proposed by Joreskog (24), we cross-validated the reduced 18-item factor structure from the pooled Los Angeles sample by using data from the Wisconsin sample. According to Joreskog's approach, a number of hypotheses may be tested in the evaluation of factorial invariance. The first hypothesis is that there are four correlated common factors in both samples. Assuming that the four dimensions or factors are supported in the two samples, one may refine the comparison by testing two more hypotheses. The first hypothesis assesses the equality of the factor loadings; the second assesses the equality of the factor loadings and the error terms.

The fit indexes for the test of the first hypothesis of four correlated common factors in both samples revealed strong support for this hypothesis (CFI=.97, NNFI=.96, standardized RMR=.068). The second hypothesis, that the four factors have equal factor loadings in both samples, was also supported (CFI=.97, NNFI=.96, standardized RMR= .073). There was marginal evidence that the influence of error variance on each item was the same across the two sites (CFI=.97, NNFI= .96, standardized RMR=.09). Given the likelihood of multiple sources of random error in administering an instrument across sites, it would be exceedingly difficult to find that the influence of such errors is operating in equivalent ways on items across sites (24).

Finding support for the cross-validation of the factor structure across the two study sites, we combined the Los Angeles samples and the Wisconsin sample and reran the confirmatory factor analysis. Table 2 reports the completely standardized factor loadings for the combined samples as well as the individual item means and standard deviations.

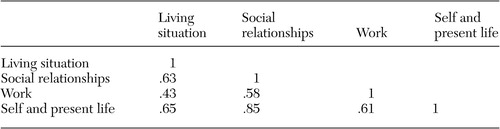

Table 3 reports the correlations between the factors using the combined Los Angeles and Wisconsin samples. Noteworthy in Table 3 is the high correlation (.85) between the satisfaction with social relationships and the satisfaction with self and present life factors. Despite the strength of this correlation, we believe that separate factors are appropriate, because satisfaction with social relationships and satisfaction with self and present life are conceptually distinct constructs. A high correlation between them is not unexpected given the reported importance of social relations to psychological and general well-being among both mental health consumers and the general population.

Internal reliability. Using Cronbach's alpha, we examined the internal reliability of the four subscales in the 18-item scale at baseline and six months in the Los Angeles and Wisconsin samples. Acceptable reliability was evident for three subscales: the alpha coefficients for living situation were .74 and .76; for social relationships, .80 and .81; and for self and present life, .83 and .82. The internal reliability of the work subscale was lower (alpha coefficients of .61 and .74), likely in part because this subscale has only two items.

Relationship with life conditions

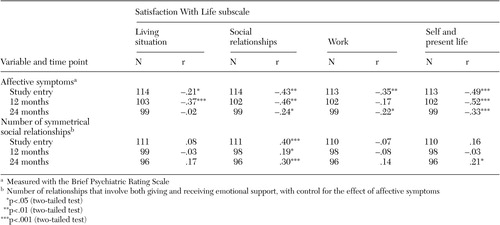

Affective symptoms. In the Wisconsin sample, affective symptoms had been measured at each six-month follow-up period by using the affective scale of the BPRS. The correlations of BPRS affective symptoms with each of the four Satisfaction With Life subscales at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months are shown in Table 4. The results support our hypothesis that affective symptoms are negatively correlated with all the Satisfaction With Life subscales and have the strongest negative relationship with the self and present life subscale.

Social relationships.Table 4 shows the results for the test of our hypothesis that clients who report a greater number of symmetrical relationships will demonstrate greater satisfaction with their social relationships and with self and present life than clients who report fewer symmetrical relationships. Symmetrical social relationships are those that involve both giving and receiving emotional support. After controlling for affective symptoms, we found that the number of symmetrical relationships was significantly correlated with satisfaction with social relationships at all three time points. The number of symmetrical relationships was not related significantly to other Satisfaction With Life subscales, except at 24 months, when it was positively related to satisfaction with self and present life.

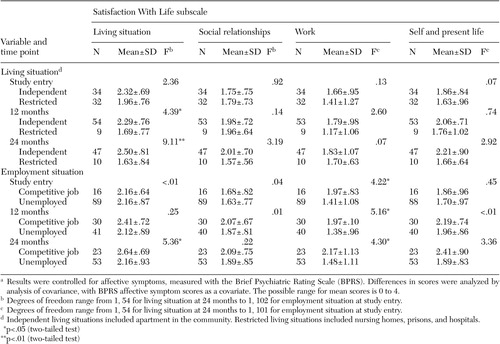

Living situation. To test our hypothesis, while controlling for affective symptoms, that clients living in independent situations, such as apartments in the community, will report higher satisfaction with their living situations than those living in restricted settings, such as nursing homes, prisons, and hospitals, we considered only the data from participants who were residing in these types of settings on the date of the interview. As Table 5 shows, at 12 months and 24 months, participants living in independent living situations reported significantly higher levels of satisfaction with their living situation than those residing in restricted settings. The results were in the same direction, although nonsignificant, at baseline. Type of living situation was not related to any of the other three satisfaction domains.

Employment status. Our third hypothesis, with control for affective symptoms, was that individuals who were employed in competitive jobs would express higher levels of work satisfaction than those who were unemployed. We did not expect that work status would be related to satisfaction with living situation, social relationships, or self and present life. As shown in Table 5, at all three time points, clients who were working in competitive jobs expressed significantly higher levels of work satisfaction than those who were unemployed. The only relationship of employment status to any of the other three Satisfaction With Life subscales was at the 24-month interview, when work status was also related to satisfaction with living situation. Clients who are in competitive employment may have more resources and therefore may have more control over where they live, which might lead to higher levels of satisfaction with their living situation.

Discussion and conclusions

Our results provide considerable support for the construct validity of the revised 18-item Satisfaction With Life scale administered to adults with schizophrenia or schizophrenia spectrum disorders. (The scale and its instructions may be viewed and downloaded by clicking the appropriate link from www.dhfs.state.wi.us/mh_mendota/programs/outpatient/pact/pact.htm.) The invariance of the scale's structure across samples of such individuals with quite different demographic characteristics (Table 1) bodes well for the instrument's potential generalization and use with other samples of individuals with these illnesses. The Satisfaction With Life scale assesses an individual's subjective satisfaction with his or her current life in four domains: living situation (items 1 to 4), social relationships (items 5 to 10), work (items 12 and 13), and self and present life (item 11 and items 14 to 18). A respondent's mean score for each of the four domains should be calculated. It is neither psychometrically nor theoretically appropriate to simply sum all 18 items of the scale to gain a measure of "overall" life satisfaction.

A next step in validating the Satisfaction With Life scale is to examine the temporal invariance of the scale's factor scales by studying their stability over time. Furthermore, validation of the scale with other client groups is necessary to extend its external validity beyond use with persons with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-related disorders. In addition, study of the ability of the subscales of the Satisfaction With Life scale to detect predicted changes in satisfaction across time is necessary. In this regard, it is encouraging that the means and standard deviations of the scale items (displayed in Table 2) suggest that ceiling effects are not a problem. Absence of ceiling effects is essential if an instrument is to have the ability to reflect positive change (25).

The Satisfaction With Life scale is one psychometrically supported measure that can be used for assessing aspects of subjective quality of life among persons with serious mental illness. From the range of tools now available for assessing the quality of life of persons with serious and persistent mental illness (9,26), at least four other instruments provide measurement of the construct of concern here, "subjective satisfaction with life": Lehman's Quality of Life Interview (8); the Lancashire Quality of Life Profile (27), which is based on Lehman's instrument; the Quality of Life Index for Mental Health (28); and Frisch's Quality of Life Inventory (29). These life satisfaction scales are based on an earlier scale developed in Andrews and Withey's 1976 study of general well-being in American life (30). Compared with the Satisfaction With Life scale, the four scales cover a much wider range of life domains—eight to 17 domains—and, therefore, provide superior "content validity." In addition, the first three—Lehman's Quality of Life Interview, the Lancashire Quality of Life Profile, and the Quality of Life Index for Mental Health—are embedded within a longer comprehensive assessment designed to measure additional, "objective" aspects of quality of life, including functioning and life conditions. A feature of the Quality of Life Index for Mental Health and Frisch's Quality of Life Inventory is the addition of questions asking the individual to weight the importance of each domain; these weightings are then taken into account in overall scoring. Finally, the Quality of Life Index for Mental Health also includes versions to measure the consumer's quality of life from the perspectives of family members and providers.

We applaud the advancements and enhancements made in these newer scales. At the same time, there remains a place for the Satisfaction With Life scale in clinical and services program evaluation research. The Satisfaction With Life scale is a brief, easily completed freestanding scale that adequately addresses several important domains of subjective quality of life; for measurement of other critical variables, such as psychiatric and psychosocial functioning and life conditions, investigators can choose from among a wide range of available instruments (31). In addition, the Satisfaction With Life scale's self and present life subscale appears to be unique among subjective satisfaction measures, because it captures some of the self-related concepts—including satisfaction with one's current psychological condition and with oneself as a whole, satisfaction with the current amount of enjoyment and freedom one experiences, and satisfaction with one's present life—that consumers are now reporting to be extremely important to them in their overall life satisfaction, well-being, and recovery (32,33).

The Satisfaction With Life scale, like all measures of subjective satisfaction with life, must be used thoughtfully in evaluation research. During hypothesis development, testing, and interpretation of findings, known issues with these instruments must be kept in mind. One such issue is the consistently found relationship between subjective satisfaction with life and present affective state (8,19,20,21). In addition, although existing measures of satisfaction with life have demonstrated expected increases or decreases after quite major interventions or environmental changes, their sensitivity to more subtle, or even moderate, changes remains in considerable question (34,35).

Taking a long-term perspective, we believe that adequate measurement of subjective quality of life among persons with severe and persistent mental illness is still very much a work in progress. Despite the seminal step by Lehman (8) in the 1980s to introduce theoretical considerations based on the work of Campbell, Converse, and Rodgers (36) and Andrews and Withey (30), theory concerning subjective quality of life among persons with mental illness remains poorly developed (10,37). In addition, little is known about the predictors of life satisfaction among persons with serious mental illness (37). Measures such as the Satisfaction With Life scale's self and present life subscale can be used to advance conceptual understanding by serving as a dependent variable in exploratory or theory-testing studies aimed at increasing our understanding of the variables that contribute to subjective quality of life among persons with severe mental illnesses (38,39).

The times indeed appear ripe for advancement. Investigators such as Rosenfield (38), Angermeyer and Kilian (40), and Barry (37) are putting forth more sophisticated models of the factors that contribute to and mediate perceived quality of life among persons with long-term mental illness. It is important to note that consumers are speaking out about what matters most to them. New variables are being emphasized, including empowerment and self-determination, a sense of control and ability to manage one's symptoms, a sense of meaning and purpose, a sense of hope, a feeling of being part of the community, and a positive sense of self (7,32,33,41). These developments are exciting and important, leading us to predict that in a decade or so, the content of measures to assess subjective quality of life among mental health consumers will be quite different from that of the measures that currently exist.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Mendota Mental Health Institute and the State of Wisconsin Division of Health and Family Services for their long-term support of Mendota's Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT). The Satisfaction with Life Scale was developed for use in the evaluation of Mendota's PACT program in Madison, Wisconsin, where the Wisconsin sample data in the analyses reported here were collected.

Dr. Test and Dr. Greenberg are affiliated with the School of Social Work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1350 University Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Greenberg is also with the Waisman Center at the University of Wisconsin. Dr. Long is with the research methodology program of the department of educational psychology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Dr. Brekke is with the School of Social Work at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Ms. Senn Burke is with the program of assertive community treatment at Mendota Mental Health Institute in Madison, Wisconsin.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of adults with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-related disorders receiving community treatment at three sites in a study of the construct validity of the Satisfaction With Life scalea

a The dates of data collection were 1990 to 1995 for Los Angeles site 1, 1995 to 2000 for Los Angeles site 2, and 1978 to 1986 for Wisconsin.

|

Table 2. Mean scores on items of the 18-item Satisfaction With Life scale of the 484 adults with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-related disorders in the combined Los Angeles and Wisconsin samples and standardized factor loadings from a confirmatory factor analysis of the hypothesized four-domain structure of the scale using the combined samplea

a Data were from consumers at two sites in Los Angeles (N=166 and N=172, respectively) and one in Wisconsin (N=146). For all but item 17, the Likert response options, scored 0 to 4, were not at all, very little, average or OK, a lot, and a great deal. For item 17, the response options, scored 0 to 4, were definitely no, somewhat, average, a lot, and definitely yes.

|

Table 3. Pearson product-moment correlations of factors from a confirmatory factor analysis of the hypothesized four-domain structure of the 18-item Satisfaction With Life scale

|

Table 4. Pearson product-moment correlation between Satisfaction With Life subscale scores and measures of affective symptoms and symmetrical social relationships at study entry and 12- and 24-month follow-ups among adults with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-related disorders receiving community treatment at the Wisconsin study site

|

Table 5. Scores on the Satisfaction With Life subscales of adults with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-related disorders receiving community treatment at the Wisconsin study site, by living situation and employment situation at study entry and at 12- and 24-month follow-upsa

a Results were controlled for affective symptoms, measured with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Differences in scores were analyzed by analysis of covariance, with BPRS affective symptom scores as a covariate. The possible range for mean scores is 0 to 4.

1. Attikisson C, Cook J, Karno M, et al: Clinical services research. Schizophrenia Bulletin 18:561–626, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kravetz S, Faust M, Dasberg I: A comparison of care consumer and care provider perspectives on the quality of life of persons with persistent and severe psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25:388–397, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Sainfort F, Becker M, Diamond R: Judgments of quality of life of individuals with severe mental disorders: patient self-report versus provider perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:497–502, 1996Link, Google Scholar

4. Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001Google Scholar

5. Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:11–23, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Bracke P: Measuring the subjective well-being of people in a psychosocial rehabilitation center and a residential psychiatric setting: the outline of the study and the measurement properties of a multidimensional indicator of well-being. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:222–236, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Corring DJ: Quality of life: perspectives of people with mental illness and family members. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25:350–358, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51–62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Lehman AF: Instruments for measuring quality of life in mental illness, in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

10. Katschnig H: How useful is the concept of quality of life in psychiatry? in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

11. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392–397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Test MA, Stein LI: Training in Community Living: research design and results, in Alternatives to Mental Hospital Treatment. Edited by Stein LI, Test MA. New York, Plenum, 1978Google Scholar

13. Fairweather GW, Sanders DH, Maynard H, et al: Community Life for the Mentally Ill: An Alternative to Institutional Care. Chicago, Aldine, 1969Google Scholar

14. Test MA, Knoedler WH, Allness DJ: The long-term treatment of young schizophrenics in a community support program. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 26:17–27, 1985Google Scholar

15. Test MA, Knoedler WH, Allness DJ, et al: Comprehensive community care of persons with schizophrenia through the Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT), in Toward a Comprehensive Therapy for Schizophrenia. Edited by Brenner HD, Boker W, Genner R. Seattle, Wash, Hogrefe & Huber, 1997Google Scholar

16. Brekke JS, Long JD, Kay DD: The structure and invariance of a model of social functioning in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 190:63–72, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Joreskog KG, Sorbom D: Lisrel 8 User's Reference Guide. Chicago, Scientific Software International, 1996Google Scholar

18. Joreskog KG: Similtaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika 57:409–426, 1971Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Corrigan PW, Buican B: The construct validity of subjective quality of life for the severely mentally ill. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:281–285, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, et al: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 29:321–326, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mechanic D, McAlpine D, Rosenfield S, et al: Effects of illness attribution and depression on the quality of life among persons with serious mental illness. Social Science and Medicine 39:155–164, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Overall JE, Klett CJ: Applied Multivariate Analysis. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1972Google Scholar

23. Hu LU, Bentler PM: Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods 3:424–453, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Joreskog KG: Advances in Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Models. Cambridge, Mass, Abt Books, 1979Google Scholar

25. Hyland ME: A brief guide to the selection of quality of life instrument. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 1:24, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Van Niewenhuizen C, Schene AH, Boevink WA, et al: Measuring the quality of life of clients with severe mental illness: a review of instruments. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 20:33–41, 1997Google Scholar

27. Oliver J, Huxley P, Bridges K, et al: Quality of Life and Mental Health Services. London, Routledge, 1996Google Scholar

28. Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F: A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Quality of Life Research 2:239–251, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Frisch MB, Cornell J, Villaneuva M, et al: Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory: a measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychological Assessment 42:92–101, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Andrews FM, Withey SB: Social Indicators of Well-Being. New York, Plenum, 1976Google Scholar

31. American Psychiatric Association: Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

32. Ridgway P: Restorying psychiatric disability: learning from first person recovery narratives. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 24:335–343, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Young SL, Ensing DS: Exploring recovery from the perspective of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 22:219–231, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Barry MM, Crosby C: Quality of life as an evaluative measure in assessing the impact of community care on people with long-term psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:210–216, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Cheng S: Subjective quality of life in the planning and evaluation of programs. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:123–134, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Campbell A, Converse PE, Rodgers WL: The Quality of American Life. New York, Russell Sage, 1976Google Scholar

37. Barry MM: Well-being and life satisfaction as components of quality of life in mental disorders, in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

38. Rosenfield S: Factors contributing to the subjective quality of life of the chronic mentally ill. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 33:299–315, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Rosenfield S, Neese-Tood S: Elements of a psychosocial clubhouse program associated with a satisfactory quality of life. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:76–78, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

40. Angermeyer MD, Kilian R: Theoretical models of quality of life for mental disorders, in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

41. Smith MK: Recovery from a severe psychiatric disability: findings of a qualitative study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:149–158, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar