Patterns and Quality of Treatment for Patients With Schizophrenia in Routine Psychiatric Practice

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study provided generalizable national data on the treatment of adult patients with schizophrenia in the United States and assessed conformance with the practice guideline treatment recommendations of the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team and the American Psychiatric Association. METHODS: National data from the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's 1999 Practice Research Network study of psychiatric patients and treatments were used to examine treatment patterns for 151 adult patients with schizophrenia. Analyses were performed and adjusted for the weights and sample design to generate nationally representative estimates. RESULTS: Findings indicated that patients with schizophrenia who were treated by psychiatrists had complex clinical problems and were markedly disabled. Forty-one percent of patients had a comorbid axis I disorder, and 75 percent were currently unemployed. Thirty-five percent were currently experiencing medication side effects, and 37 percent were currently experiencing problems with treatment adherence. Although most patients received guideline-consistent psychopharmacologic treatment, treatment was characterized by significant polypharmacy. Rates of conformance with the guideline recommendations were significantly lower for psychosocial recommendations than for psychopharmacologic recommendations. Although 69 percent of patients received at least some psychosocial treatment, none of the unemployed patients received vocational rehabilitation services in the past 30 days. CONCLUSIONS: These data suggest unmet need for psychosocial treatment services among individuals with schizophrenia. These findings raise questions about whether currently available antipsychotic medications are being used optimally or whether they offer limited effectiveness for patients with complex clinical problems who are treated in routine psychiatric practice.

The treatment of schizophrenia has changed dramatically in recent years with the development of new pharmacologic treatments and the accumulation of evidence for effective psychosocial treatments. Six second-generation antipsychotics are now available, increasing treatment options for patients with schizophrenia (1,2). In addition, antidepressants, antianxiety medications, and mood stabilizers are commonly used adjunctive medications (3,4,5), which has resulted in polypharmacy treatment practices, including the use of two or more antipsychotics (6). Also, evidence that supports the use of psychosocial interventions, such as family therapy and social skills training, has increased the number of treatment options for physicians to consider (7).

To improve and standardize quality of care for patients with schizophrenia and to guide clinical decisions, practice guidelines and treatment recommendations have been developed, including the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team's (PORT's) recommendations and the American Psychiatric Association's (APA's) practice guideline (8,9,10,11). The PORT recommendations provide concise, rigorously derived statements that aim to represent unbiased summaries of available scientific research that covers a range of treatments. Similarly, the APA has published and recently revised a summary of available data as a practice guideline (2,8).

Studies have analyzed patterns of treating patients with schizophrenia in specific regions or service settings and conformance with selected practice guideline recommendations (12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19). Analyses of conformance with evidence-based practice guideline recommendations are of particular interest because these recommendations provide accepted measures of quality (20). Because of concerns that recommended evidence-based treatments may not be effective for a significant portion of patients in routine practice, there is particular interest in studying patterns and outcomes of treatments in routine practice (21).

The primary aims of this study were to obtain national data on the treatment of adult patients with schizophrenia in the United States, including the diagnostic and clinical characteristics of patients treated by psychiatrists in routine practice settings, the types and combinations of psychopharmacologic and psychosocial treatment provided, and the patterns of conformance with key PORT and APA practice guideline recommendations (8). Because psychiatrists treat an estimated 77.9 percent of patients with schizophrenia, our data reflect most patients with schizophrenia who are treated in the United States (22).

Methods

Population and data collection

This study used cross-sectional data from the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's 1999 Practice Research Network (PRN) study of psychiatric patients and treatments (SPPT). A detailed description of the methods used in the 1997 SPPT, which were replicated in this study, are described elsewhere and summarized here (23). Our study sample included 784 psychiatrists who were APA members and spent at least 15 hours per week in direct patient care. A total of 378 psychiatrists (48 percent) were randomly selected and recruited from the APA membership (58 percent of those targeted agreed to participate), and 406 psychiatrists (52 percent) were APA members who volunteered through a nationwide recruitment.

Psychiatrists who are members of the APA represent a majority of psychiatrists in the United States; at the time of this study an estimated 71 percent of the psychiatrists listed in the American Medical Association's (AMA's) Masterfile of physicians were members of the APA. Although APA members' sociodemographic characteristics are comparable to those of psychiatrists in AMA's Masterfile, APA members are more likely to be U.S. graduates and board certified.

A total of 615 psychiatrists (78 percent) completed the 1999 SPPT. Participants implemented the study on a randomly assigned start day and time and provided general information on the next 12 consecutive patients seen in treatment. More clinically detailed data were provided for three of these 12 patients. The study was reviewed by the APA's institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from the participating psychiatrists. All patients were passively informed about the PRN and data collection activities. No personal identifying patient information was collected with the SPPT. Psychiatrists provided detailed clinical data on 1,843 patients. A total of 127 psychiatrists reported data on 151 adults (9.7 percent of the total adult patient sample) who were given a diagnosis of schizophrenia by the participating psychiatrists. The adult patients with schizophrenia were the focus of the study presented here.

Study measures

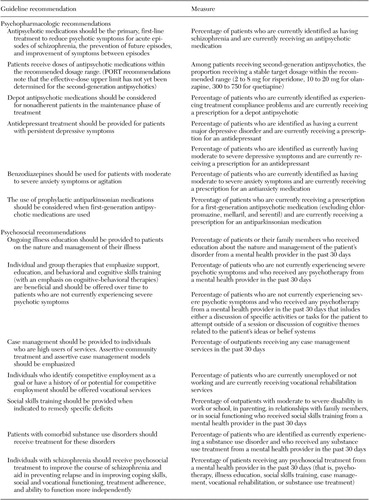

The 1999 SPPT database was used to select key psychopharmacologic and psychosocial guideline recommendations that could be used or approximated to examine related treatment patterns. Table 1 provides a summary of these guidelines. Tables 2, 3, and 4 list the variables examined in this study, including psychosocial treatments provided by the psychiatrist and other providers in the past 30 days. To assess conformance with practice guidelines, we used evidence-based treatment recommendations that were available when the 1999 SPPT was implemented: the 1998 PORT guideline and the 1997 APA guideline.

Statistical analysis

To generate national estimates, three-stage propensity score weights were used. The first stage adjusted for discrepancies between a random sample of APA members who responded to the 1998 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice (NSPP) and the APA membership population profile on variables known to the APA about all members—for example, age, sex, race or ethnicity, and certification (24). The NSPP provides the best available national practice data source to weigh the data. The second stage adjusted for discrepancies between the PRN psychiatrists and the NSPP sample profile of APA member psychiatrists on relevant demographic information and the extensive set of characteristics assessed in the NSPP. The third stage adjusted for the inverse probability of patient selection by patient volume of the treating psychiatrist. To reduce the effect of outliers, quintile medians were used at each stage of the weighting.

Analyses were performed with use of SUDAAN to adjust for the weights and the nested sample design to generate nationally representative estimates (25).

Results

Sociodemographic and health plan characteristics

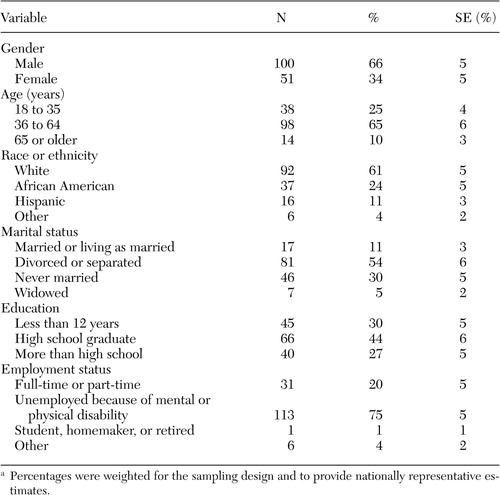

As shown in Table 2, most patients with schizophrenia in our study sample were white, middle aged and male and had a high school education or less. Most patients were not married or living as married. The most commonly used source of payment was Medicaid, followed by other government or public insurance. Only 4 percent of the patients in our sample used private insurance.

Diagnostic and clinical characteristics

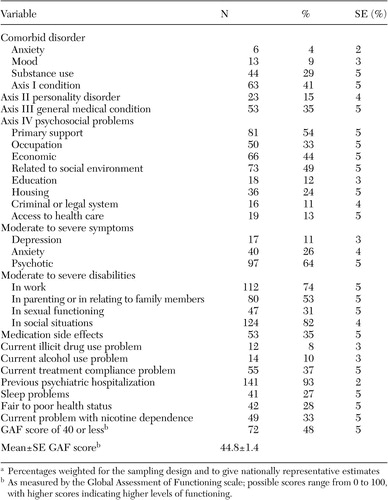

As Table 3 shows, 41 percent of the patients had comorbid axis I conditions, most commonly alcohol or other substance use disorders, followed by mood and anxiety disorders. Although 33 percent of the patients were reported to currently have problems with nicotine dependence (twice the rate of patients who did not have schizophrenia), only four patients (9 percent) were currently receiving treatment for nicotine dependence. Fifty-three patients (35 percent) had a comorbid general medical condition.

Sixty-four percent of the patients with schizophrenia were reported to currently be experiencing moderate to severe psychotic symptoms; 26 percent, moderate to severe anxiety symptoms; and 11 percent, moderate to severe depressive symptoms. The mean score on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale for patients in the study sample was 45, which indicates serious symptoms or impairment. Ninety-three percent of patients had at least one previous hospitalization for a mental disorder. Mental or physical disability precluded employment for 75 percent of the patients. A majority were reported to have moderate to severe disability in social functioning (82 percent) and in parenting or in relationships with family members (53 percent). The most common axis IV psychosocial problems were problems with the primary support group (54 percent), problems related to social environment (49 percent), and economic problems (44 percent). Current medication side effects were reported for 35 percent of the patients with schizophrenia, and treatment compliance problems were reported for 37 percent. Twenty-seven percent experienced sleep problems.

Patterns of psychosocial and psychopharmacologic treatment

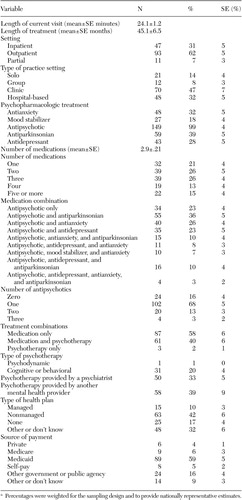

As shown in Table 4, most patients were treated in outpatient settings. The mean length of time the patients were in treatment with the psychiatrist was 45 months, and the mean length of the current visit was 24 minutes. Treatment most commonly consisted of medications alone (58 percent) and combined medications and psychotherapy (40 percent). One patient received electroconvulsive therapy. Virtually all patients (99 percent) received at least one antipsychotic, 32 percent received antianxiety medications, 39 percent received antiparkinsonian medications, 28 percent received antidepressants, and 18 percent received mood stabilizers. The mean number of psychopharmacologic medications prescribed per patient was 2.9. Sixteen percent of the patients were taking two or more antipsychotics, 82 (54 percent) were taking only second-generation antipsychotics, 47 (31 percent) were taking only first-generation antipsychotics, and 21 (14 percent) were taking both first- and second-generation antipsychotics. Table 4 lists the most commonly prescribed combinations of medications; as can be seen, 79 percent of the patients received two or more medications.

Conformance with key psychopharmacologic guidelines

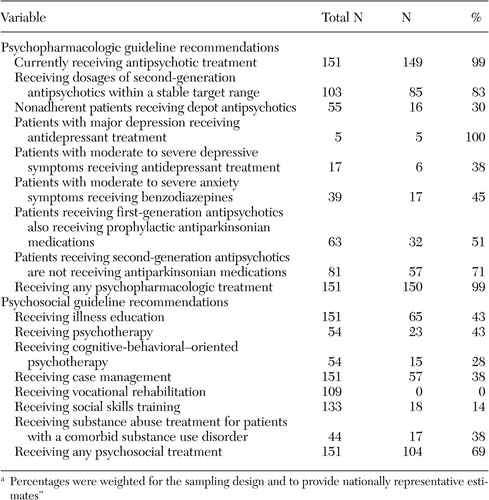

As shown in Table 5, conformance rates were relatively high for most of the psychopharmacologic recommendations studied. An exception was the infrequent use of depot antipsychotic medications. Twenty-seven patients with schizophrenia (18 percent) received depot antipsychotics, and 30 percent of patients with current treatment compliance problems received depot antipsychotics. In addition, a significant proportion of patients who were currently experiencing moderate to severe psychotic symptoms and received an antipsychotic also received mood stabilizers or benzodiazepines; however, these patients did not receive clozapine, which is recommended for patients with treatment-resistant psychotic symptoms.

Most of the patients with schizophrenia received second-generation antipsychotic dosages within the recommended maintenance ranges (83 percent). However, ten (10 percent) received stable target dosages that were greater than the recommended range, and seven (7 percent) received dosages that were less than the recommended range.

Thirty-two patients (51 percent) who received first-generation medications (excluding chlorpromazine, thioridazine, and mesoridazine because of their favorable side effect profiles) also received antiparkinsonian medications. However, 24 patients who received only second-generation antipsychotics (29 percent) (excluding patients receiving risperidone, because of the side effects associated with higher dosages of this medication) also received antiparkinsonian medications, even though antiparkinsonian medications were not recommended for patients who are taking second-generation antipsychotics (26). Although only a small sample of patients had major depressive disorder, all these patients received an antidepressant. However, only six patients with moderate to severe depressive symptoms (38 percent) received antidepressants.

Conformance with key psychosocial guideline recommendations

As indicated in Table 5, rates of conformance with the guideline recommendations were significantly lower for psychosocial recommendations than for psychopharmacologic recommendations: for psychosocial recommendations rates ranged from 0 percent to 43 percent, whereas for psychopharmacologic recommendations rates ranged from 30 to 100 percent. Overall, 69 percent of the patients received at least some psychosocial treatment. However, among patients who were currently unemployed as a result of a mental or physical disability, none received vocational rehabilitation. Among patients with deficits in social skills functioning, only 14 percent received social skills training in the past 30 days. Although 43 percent of patients or their family members received illness education from a mental health provider and 43 percent of the patients received psychotherapy from a mental health provider, only 28 percent of the patients received cognitive-behavioral oriented psychotherapy from their treating psychiatrist.

Thirty-eight percent of the patients were reported to have received some form of case management in the past 30 days. Although substance use disorders were the most commonly reported axis I disorder, only 38 percent of patients with such disorders received treatment for their substance use disorder.

Discussion

Study strengths and limitations

Although this study provided clinically detailed nationally representative data that reflect patients with schizophrenia who are treated by APA member psychiatrists in the full range of treatment settings, the study had several limitations. First, the study relied on psychiatrist-reported data and had limited data on the clinical context of treatment in terms of phase of illness, treatment history, and response to treatment. These limitations make it difficult to determine and model the extent to which psychiatrists are providing treatment that is consistent with many of the guideline recommendations. For example, for a majority of patients currently experiencing moderate to severe psychotic symptoms, we know the percentage of patients currently receiving clozapine; however, we do not know the proportion who ever received an adequate trial of another antipsychotic and whether these patients were ever offered or prescribed clozapine. Because of these limitations many of our guideline-conformance measures are somewhat crude. Because we do not have data on the indications for which medications were prescribed, we do not know whether benzodiazepines were prescribed for anxiety, agitation, sleep problems, or treatment-resistant psychotic symptoms. APA and PORT recommendations caution against using benzodiazepines for treatment-resistant psychotic symptoms.

We also did not have data on consumer preferences and the extent to which treatments were ever offered or provided to patients—for example, depot medications, psychotherapy, and vocational rehabilitation. With respect to the psychosocial recommendations studied, we did not have data on the type of case management or on the indications for vocational rehabilitation. Reliance on psychiatrist-reported data of treatments provided in the past 30 days may also significantly underestimate some measures, including side effects, treatment adherence, and substance use.

Because of the clinical caveats surrounding the guidelines, it was difficult to determine whether many of the recommendations were followed appropriately. In addition, our data did not clearly specify the intensity, frequency, and duration of treatments. Consequently, we were able to examine only general treatment patterns related to the PORT and APA recommendations.

Summary of key findings and implications

Overall, these data indicate that patients with schizophrenia who are treated by psychiatrists have highly complex clinical problems and are markedly disabled; 75 percent of our sample were unemployed because of a mental or physical disability. Psychiatrists reported that a significant proportion of the patients were experiencing medication side effects (35 percent) and had problems adhering to treatment (37 percent).

Most patients generally appeared to be receiving guideline-consistent psychopharmacologic treatment, and rates for this type of treatment were consistent with the previous PORT research findings reported by Lehman and Steinwachs (12). Our findings showed that the psychopharmacologic treatment was characterized by significant polypharmacy, with a mean of three medications prescribed per patient. A significant proportion of patients were also receiving two or more antipsychotics, a practice that is not endorsed by the guidelines that were used for this study. In addition, a notable proportion of patients who received second-generation antipsychotics were receiving dosages above the recommended range. This study also found that a majority of patients experienced moderate to severe psychotic symptoms, even though almost all patients in our sample received at least one antipsychotic and received treatment from their psychiatrists for three years on average.

These findings raise questions about whether available antipsychotic medications are used optimally or whether available antipsychotic treatments offer limited effectiveness (as demonstrated in randomized clinical trials) for clinically complex patients treated in routine practice. Some questions about the effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments may be answered through the National Institute of Mental Health's clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness study, which is being conducted in a wide range of routine practice settings to assess the long-term effectiveness and tolerability of first- and second-generation antipsychotics.

As for whether currently available medications for the treatment of schizophrenia are being optimized in routine clinical practice, we do not have longitudinal data to characterize the extent to which patients received an adequate trial and dosage of one antipsychotic before another was added. We also do not know the extent to which clozapine was offered to or tried among patients who were receiving an adequate antipsychotic dose and actively experiencing moderate to severe psychotic symptoms.

Depot medications may be underused: 70 percent of the patients with current treatment adherence problems were not receiving depot antipsychotics. Rates of depot antipsychotic use in our study were consistent with those found by Citrome and colleagues (27). In that study rates ranged from 12 to 39 percent in 21 psychiatric hospitals in New York State. Our data also indicate that a significant proportion of patients (29 percent) who received second-generation antipsychotics may be receiving antiparkinsonian medications unnecessarily. This issue warrants follow up in light of findings that show that several second-generation antipsychotics prescribed at higher dosages may have greater than expected side effect profiles (28). In these areas clinical practice may be ahead of evidence-based guidelines.

The data that showed limited access to the psychosocial treatments that are recommended by the evidence-based guideline raises concerns. Our findings are consistent with those of Young and colleagues (29), who studied 224 patients at two public mental health clinics and found that 52 percent received inadequate psychosocial care. The rates of psychotherapy that we found in our sample were consistent with those in the PORT study (12). Although rates of vocational rehabilitation in our study were significantly lower than in the PORT study (no patients in our study compared with 23 percent), the PORT study included patients who reported looking for work or participating in a vocational rehabilitation program and patients for whom vocational rehabilitation was part of the treatment plan, regardless of whether vocational rehabilitation services were provided.

Vocational rehabilitation services for unemployed patients in our sample appeared to be nonexistent; no unemployed patients were currently receiving these services, although 14 percent of the employed patients were. This finding is particularly disturbing because of the high rates of unemployment among individuals with schizophrenia. Studies suggest that vocational rehabilitation can be effective in significantly increasing employment rates and levels of earned income in this population (14,30). Cohort and cross-sectional studies indicate that the relationship between employment outcomes and symptoms is complex, and symptom severity alone does not determine a patient's suitability for vocational rehabilitation services (31,32). A growing number of clinicians, patient advocates, and researchers have called for expanded vocational and psychosocial rehabilitation services to improve functional outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia (33,34).

The patterns that we identified are troubling for two major reasons. First, patients who are already receiving treatment from a psychiatrist would be expected to represent patients with greatest access to needed treatments. Second, for patients with public insurance, access to psychosocial treatment appears to be particularly limited: only 8 percent of patients with Medicare and 41 percent of patients with Medicaid received psychotherapy from a mental health care provider in the past 30 days. Provision of substance use treatment for this population was also strikingly low. Collectively, these data suggest considerable unmet need for psychosocial treatment services among individuals with schizophrenia.

Future research

Several future studies are being conducted or planned that can help illuminate the patterns of treatment for schizophrenia and the reasons for these patterns. In addition to the study described above on clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness, we are currently completing a study of medication management decisions in schizophrenia. Using a large, nationally representative sample of psychiatrists in routine psychiatric practice, this study will evaluate the extent to which routine medication management of schizophrenia conforms to other evidence-based treatment recommendations. Furthermore, this study will identify factors affecting clinical decision making and modifiable factors associated with not conforming with these treatment recommendations.

To assess patterns of treatment and the extent to which treatments provided are consistent with evidence-based practice guideline treatment protocols, PRN studies are now being pilot tested to capture longitudinal data on the treatment history of psychiatric patients, patient preferences, treatment adherence, and patient response and outcomes of treatment. These studies will assess the extent to which specific subgroups of patients—such as patients with different severity levels, specific comorbid axis I disorders, or significant psychosocial problems who receive different types, combinations, intensity, and duration of treatment—have superior outcomes. These data will help in assessing the extent to which some of the current clinical practices identified in this study, which are not consistent with evidence-based guideline recommendations, are associated with favorable outcomes of treatment.

Conclusions

These study findings indicate that patients with schizophrenia who are treated by psychiatrists have complex clinical problems and are markedly disabled. Although most patients received guideline-consistent psychopharmacologic treatment, it was characterized by significant polypharmacy and a majority of patients experienced moderate to severe psychotic symptoms despite receiving antipsychotic medication. These findings also suggest significant unmet need for psychosocial treatment services among individuals with schizophrenia in the United States; rates of conformance with the psychosocial practice guideline recommendations studied ranged from 0 to 43 percent.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by contract 280-01-8056 from the Center for Mental Health Services and by grant funding from the American Psychiatric Foundation. Practice Research Network (PRN) psychiatrists contributed their time to participate in the 1999 PRN Study of Psychiatric Patients and Treatments study. The authors thank Ilze Ruditis, M.S.W., and Caroline Kaufman, Ph.D., for their thoughtful comments and input.

Dr. West, Dr. Wilk, Mr. Rae, Dr. Narrow, and Dr. Regier are affiliated with the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's (APIRE's) Practice Research Network, 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825, Arlington, Virginia 22209 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Olfson is with the department of psychiatry at Columbia University in New York City. Dr. Marcus is with the School of Social Work at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Dr. Pincus is with the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and the RAND-University of Pittsburgh Health Institute.

|

Table 1. Psychopharmacologic and psychosocial recommendations for treating schizophrenia from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) and the American Psychiatric Association practice guideline

|

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of 151 patients with schizophrenia in routine psychiatric practicea

a Percentages were weighted for the sampling design and to provide nationally representative estimates.

|

Table 3. Diagnostic and clinical characteristics of 151 patients with schizophrenia in routine psychiatric practicea

a Percentages weighted for the sampling design and to give nationally representative estimates

|

Table 4. Treatment and health plan characteristics of 151 patients with schizophrenia in routine psychiatric practicea

a Percentages were weighted for the sampling design and to provide nationally representative estimates.

|

Table 5. Rates of conformance with practice guideline treatment recommendations for 151 patients with schizophrenia in routine psychiatric practicea

a Percentages were weighted for the sampling design and to provide nationally representative estimates"

1. Chakos M, Lieberman J, Hoffman E, et al: Effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:518–526, 2001Link, Google Scholar

2. Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. American Psychiatric Press, Arlington, Va, 2004Google Scholar

3. Siris SG, Bermanzohn PC, Mason SE, et al: Maintenance imipramine therapy for secondary depression in schizophrenia: a controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:109–115, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wolkowitz OM, Pickar D: Benzodiazepines in the treatment of schizophrenia: a review and reappraisal. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:714–726, 1991Link, Google Scholar

5. Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wassef AA, et al: Effect of divalproex combined with olanzapine or risperidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 28:182–192, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. McCue RE, Waheed R, Urcuyo L: Polypharmacy in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:984–989, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Huxley NA, Rendall M, Sederer L: Psychosocial treatments in schizophrenia: a review of the past 20 years. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorders 188:187–201, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(suppl 4):1–63, 1997Google Scholar

9. Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn D: The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 12B):1–58, 1996Google Scholar

10. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl, Buchanan RW, et al: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193–216, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Rush AJ, Rago WV, Crismon ML, et al: Medication treatment for the severely and persistently mentally ill: the Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:284–291, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initials results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–20, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Walkup JT, McAlpine D, Olfson M, et al: Patients with schizophrenia at risk for excessive antipsychotic dosing. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:344–348, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Evidence-based psychosocial treatment practices in schizophrenia: lessons from the patient outcomes research team (PORT) project. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry 31:141–154, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Johnson PB, Ramirez PM, Opler LA, et al: Relationship between neuroleptic dose and positive and negative symptoms. Psychological Reports 74:481–482, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Krakowski MI, Kunz M, Czobor P, et al: Long term high-dose neuroleptic treatment: who gets it and why? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:640–644, 1993Google Scholar

17. Segal SP, Cohen D, Marder SR: Neuroleptic medication and prescription practices with sheltered-care residents: a 12-year perspective. American Journal of Public Health 82:846–852, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Baldessarini RJ, Katz B, Cotton P: Dissimilar dosing with high-potency and low-potency neuroleptics. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:748–752, 1984Link, Google Scholar

19. Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: Use of pharmacy data to assess quality of pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia in a national health care system: individual and facility predictors. Medical Care 39:907–909, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance: Vol 1. Edited by Lohr KN. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1990Google Scholar

21. Zarin DA, Pincus HA, Marcus SC: The Generalizability of Findings from Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) to Routine Clinical Settings. Boca Raton, Fla, National Clinical Drug Evaluations Unit, 1998Google Scholar

22. Olfson M, Klerman GL, Pincus HA: The roles of psychiatrists in organized outpatient mental health settings. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:625–631, 1993Link, Google Scholar

23. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, Tanelian TL, et al: Psychiatric patients and treatments in 1997: findings from the American Psychiatric Practice Research Network. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:441–449, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Zarin DA, Pincus HA, Peterson BD, et al: Characterizing psychiatry with findings from the 1996 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:397–404, 1998Link, Google Scholar

25. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS: SUDAAN User's Manual, Release 7.5 ed. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1997Google Scholar

26. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, et al: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated Treatment Recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193–216, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Citrome L, Levine J, Allingham B: Utilization of depot neuroleptic medication in psychiatric inpatients. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 32:321–326, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

28. Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, et al: Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. British Medical Journal 321:1371–1376, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al: Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:611–617, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Twanley EW, Jest DV, Lehman AF: Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorder 191:515–523, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Bryson G, Bell MD: Initial and final work performance in schizophrenia: cognitive and symptoms predictors. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorder 191:87–92, 2003Medline, Google Scholar

32. Hoffman H, Kupper Z, Zbinden M, et al: Predicting vocational functioning and outcome in schizophrenia outpatients attending a vocational rehabilitation program. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:76–82, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Bellack AS, Brown SA: Psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry Reports 3:407–412, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Voit S: Intervention options: participation in work activities for people with schizophrenia. Work 16:139–151, 2001Medline, Google Scholar