A Longitudinal Perspective on Monitoring Outcomes of an Innovative Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The use of outcome assessment to evaluate the performance of programs over many years of operation is becoming an increasingly important aspect of health care management. Over a five-year period of program monitoring, this study examined changes in individual client outcomes three months after discharge from a residential work therapy program for veterans with severe substance use disorders. The study also examined the relationship between these outcomes and changing program features, such as staffing, treatment variables, and follow-up rates. METHODS: Data on admissions characteristics, services delivered during treatment, and status at discharges were collected for 3,390 veterans who were treated in 25 sites in the Department of Veterans Affairs' Compensated Work Therapy/Transitional Residence program. Follow-up data were gathered three months after discharge for 1,771 veterans (52.2 percent). Hierarchical linear modeling was used to examine the association between year of discharge, site-level measures of program staffing and follow-up rate, and individual patient-level treatment variables and outcomes. RESULTS: Over the five-year monitoring period, site staff-to-bed ratios and follow-up rates dropped substantially, and veterans attended more Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings and had more toxicology screens. Higher staff-to-bed ratios were associated with more positive employment outcomes, and higher follow-up rates were associated with poorer outcomes in substance abuse and lower total income. However, no significant outcome trends were observed in clinical follow-up measures after the analyses adjusted for these factors, suggesting that program effectiveness did not deteriorate during a period of program change. CONCLUSIONS: Long-term evaluations of program process and follow-up status can usefully document sustained program effectiveness over many years. Such efforts should enhance their value by examining and adjusting for the impact of factors such as changing staffing levels and follow-up rates.

There has been a growing emphasis in recent years on accountability and performance assessment in mental health care (1,2,3). Major accrediting agencies require that programs systematically monitor clients' health status during and after treatment. However, few providers collect systematic data in an ongoing way (4), and few examples of sustained monitoring of health status have been presented in the literature (3).

Most research of performance monitoring has presented data from relatively small, time-limited clinical samples identified primarily for research purposes (5). Because one of the primary goals of performance monitoring is to ensure that the quality and effectiveness of a given program is maintained over extensive periods, data must be gathered by using the same methods over many years. It is inevitable that programs change over time as a result of internal reengineering efforts, changes in external administrative conditions, or reduced resource availability. Thus an important additional task for outcomes monitoring is to determine whether follow-up status of clients gets better or worse over time and why.

We know of only one empirical report on an effort to examine changes in follow-up status over an extended period (3). However, that study was purely descriptive and did not address the potential impact of staffing changes on program performance, nor did it address the potentially biasing effect of variability in follow-up rates (the proportion of program participants whose health status was successfully evaluated). Follow-up rates may vary considerably over the years, because outcome-monitoring data are often collected by administrative staff, who are subject to reductions in tight fiscal environments. It is possible that with fewer staff available to interview clients, follow-up rates are likely to be lower and that better- functioning clients will be preferentially interviewed.

In 1990 the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) established the Compensated Work Therapy/Transitional Residence (CWTTR) program, an innovative program that serves as a rehabilitative bridge to independent community living for veterans with refractory substance abuse and other complicating problems (6,7). The CWTTR program provides community-based residential treatment, while requiring participation in a vocational therapy program and personal responsibility for paying rent and maintaining the residence. Systematic follow-up monitoring has been legislatively required and is an ongoing feature of program administration.

We considered whether changes in follow-up status were correlated with changes in staffing, treatment variables, or follow-up rates. We hypothesized that reduced staffing would be associated with poorer follow-up status and that programs with lower follow-up rates would show spuriously superior health status at follow-up, because patients who are available for follow-up interviews are likely to be doing better than others, especially in the case of substance abuse programs in which patients who relapse often drop out of treatment.

Methods

Program description

The CWTTR is a rehabilitative program that puts a strong emphasis on responsible community living and workplace collaboration in the treatment of severe substance abuse. Entry requirements include evidence of a substance use problem along with a comorbid psychiatric disorder, disability, or homelessness. Clients are referred primarily from other VA substance abuse programs to address severe addiction problems that require intensive and prolonged treatment in a structured setting. The average length of stay is about six months, but stays may extend to two years. The program includes three key services: residential treatment, provided in community settings where veterans live together and share responsibility for paying their rent and maintaining their residence; required participation in a therapeutic work-for-pay program; and outpatient treatment for substance abuse at the residence (where urine toxicology screening is typically required as part of the treatment), at VA outpatient clinics, and at Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings (6,7).

Sample

As part of a national CWTTR follow-up initiative all veterans are assessed by program administrative staff with a structured interview at entry and three months after discharge—in person whenever possible and by phone if necessary.

Measures

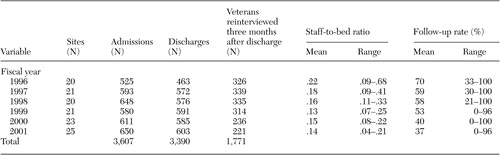

Staffing levels. At the end of each fiscal year each CWTTR site submits a structured report that documented information about the number of operational beds and the total number of full-time-equivalent employees who work in the program. This information was used to calculate staff-to-bed ratios for each fiscal year for fiscal years 1996 through 2001. Over the six fiscal years studied, annual average program-wide staff-to-bed ratios declined from .22 to .14 (Table 1).

Follow-up rates. Follow-up rates were determined by dividing the number of veterans reinterviewed three months after discharge by the total number of veterans discharged within each fiscal year. Average follow-up rates across all sites declined over the study period, from 70 to 37 percent.

Treatment variables. We documented summary information on services delivered to individual veterans for the entire episode of residential treatment: the average number of hours worked per week, the average total weekly employment earnings, the average number of toxicology screens performed per week (reflecting close monitoring of substance use), and the average number of AA and NA meetings attended per month. On discharge clinicians also documented each veteran's length of stay and mode of program discharge (successfully completed program, asked to leave the program because of an infraction of program rules, or dropped out of program).

Clients' subjective experiences of the residence were assessed with the 40-item version of the Community-Oriented Programs Environment Scale (COPES), which was administered one month after admission to the program (8). Mean scores on nine of the ten subscales were combined to form a single COPES score (Cronbach's alpha=.80).

The Work Environment Scale, a social environment instrument similar to the COPES, was used to assess the veterans' experience with the therapeutic work-for-pay component of the program one month after admission (Cronbach's alpha=.85) (9).

Follow-up measures

Self-report outcome data were available for 1,771 veterans who were reinterviewed three months after discharge. Status was assessed at baseline and follow-up in three clinical domains and included psychiatric status, community adjustment, and residential status.

Psychiatric status. Alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems were assessed with composite indexes from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (10). This index is widely used and well validated for measuring substance abuse; however, it is not well validated for measuring psychiatric symptoms. An additional dichotomous measure was used to represent whether the veteran had been sober (no use of alcohol or drugs) in the past three months.

Community adjustment. Employment was measured by a single question that asked the number of days each veteran had worked for pay in the past 30 days. Income was assessed with two measures, employment income in the past 30 days and total income from all sources in the past 30 days. The size of each veteran's social network was evaluated with questions about the number of people in various categories that the veteran felt close to. A social contact scale determined the frequency of face-to-face contact with people that the veteran felt close to.

Residential status. Residential status was assessed by a series of questions specifying where the veteran slept during the 180 days before the admission assessment and during the 90 days before the follow-up interview. To accommodate the discrepancy in time frames, the number of days the veteran spent in any setting during the 180 days before admission to the program was halved in pre-post comparisons.

Analyses

First, a series of paired t tests were used to test the magnitude and significance of overall change in mental health measures, community adjustment, and residential status from the baseline to the follow-up interview.

Second, bivariate correlations were examined between site-level measures of program staffing (staff-to-bed ratio) and follow-up rates and the year in which each veteran was discharged from the program, represented by a continuous measure ranging from 1996 to 2001.

Third, hierarchical linear modeling was used to examine the association between year of discharge, site-level measures of program staffing and follow-up rates, and individual patient-level treatment variables for the entire sample (N=3,390) and follow-up status three months after discharge (N=1,771). In standard regression analyses the assumption is made that the observations are independent. However, data from individuals discharged from the same program may be correlated, thus violating the assumption. Such correlation is especially problematic in the case of site-level data in which all individuals from a given site in a given year have the same value (for example, for follow-up rate or staffing). Hierarchical linear modeling is used to adjust the standard errors for the correlated nature of the data—that is, for the fact that the observations from a given site in a given year are not independent (11). The PROC MIXED procedure of SAS software system (12) was used for these analyses and included covariates to adjust for the risk of potentially confounding admission characteristics that were correlated with year of discharge (age, race or ethnicity, days homeless, employment status, income, incarceration, social contacts, and ASI composite scores for problems with alcohol, drugs, and psychiatric symptoms).

Results

Sample

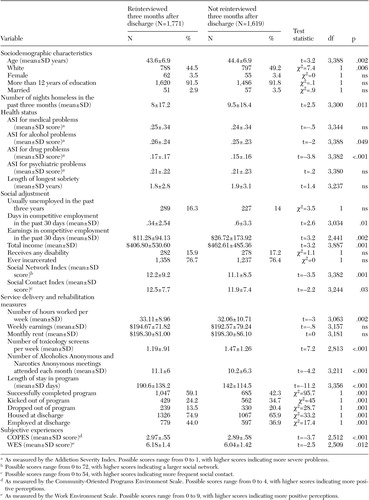

As shown in Table 1, from October 1995 to September 2001 a total of 3,390 veterans completed an episode of treatment at 25 sites across the country. Follow-up data were available for 1,771 veterans (52.2 percent). As shown in Table 2, compared with veterans who were not reinterviewed, those who were had somewhat different baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Veterans who were reinterviewed were slightly younger, were more likely to be nonwhite, had lower total monthly incomes, and had more serious alcohol and drug problems. They also had longer stays and were more likely to have had a mutually agreed discharge. Reinterviewed veterans had greater need of VA assistance and may have been more committed to recovery.

Clinical status

Veterans reinterviewed three months after discharge experienced statistically significant improvement in all outcomes: psychiatric status, community adjustment, and residential status (data available on request).

Program staffing, follow-up, and year of discharge

Correlations of year of discharge with site follow-up rates and staffing ratios revealed that from fiscal year 1996 to fiscal year 2001 site follow-up rates and staff-to-bed ratios dropped significantly (Pearson correlation coefficient for year of discharge and site follow-up rates=-.42, p=.001; Pearson correlation coefficient for year of discharge and site staff-to-bed ratios=-.39, p=.001). A statistically significant positive correlation was also seen between site staff-to-bed ratios and site follow-up rates (Pearson correlation coefficient=.27, p=.003). Thus, as staffing declined over time, so did the follow-up rates. This finding is not surprising because administration of follow-up interviews were the responsibility of program staff who were likely to have given greater priority to delivering clinical services than to locating veterans and administering follow-up questionnaires.

Year of discharge, staff-to-bed ratio, and treatment variables

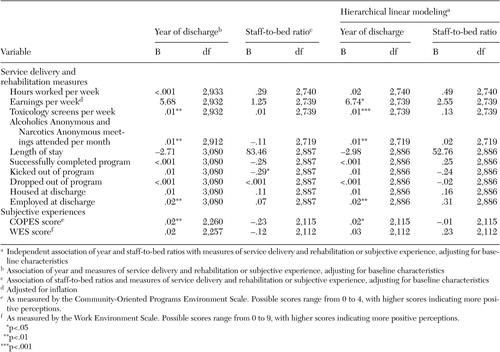

As shown in Table 3, year of discharge was significantly associated with three treatment variables at the level of individual clients. Over the course of the study, more toxicology screens were performed each week, more AA and NA meetings were attended each month, and veterans had a more favorable perception of the residential treatment environment, as measured by the COPES index.

The staff-to-bed ratio was negatively associated with the proportion of veterans released from the program prematurely as a result of infraction of program rules but not with other measures of treatment variables (Table 3).

When the year of discharge and staff-to-bed ratio were both entered in the hierarchical linear models, no significant associations were found between staffing and any of the measures of the treatment variables (Table 3). However, year of discharge remained associated with all four treatment measures. In addition, weekly earnings in the work-for-pay program were found to have increased over the years, when analyses controlled for inflation. Thus reductions in staff did not seem to adversely affect service use, because the significant relationship between year of discharge and service use was not altered when the staff-to-bed ratio was included as a covariate.

Follow-up status

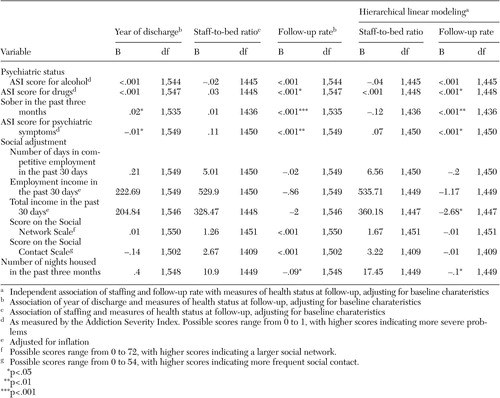

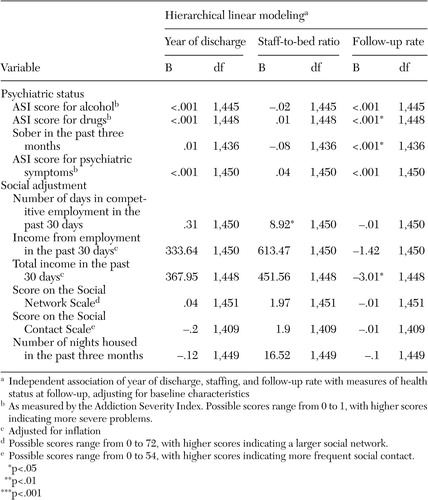

The first set of follow-up analyses separately examined the relationship of year of discharge, staff-to-bed ratio, and follow-up rates with each of the ten follow-up measures. Over the years a larger proportion of veterans were sober three months after completing treatment and experienced significantly greater improvement in their psychiatric symptoms. As shown in Table 4, no associations were noted between staffing and these measures. As hypothesized, higher follow-up rates were associated with poorer status on measures of psychiatric symptoms, substance abuse, and housing.

In the second set of analyses, staff-to-bed ratios and follow-up rates were both included in the hierarchical linear models (Table 4). Again, no associations were noted between staffing and follow-up status. Higher follow-up rates were still associated with poorer status on measures of psychiatric and substance abuse symptoms and housing. In addition, higher follow-up rates were negatively associated with total income at follow-up.

In the last set of outcome analyses, year of discharge, staff-to-bed ratio, and follow-up rates were included in the hierarchical linear models to examine the independent relationships of each of these measures to follow-up status. As shown in Table 5, no significant associations were observed between year of discharge and any of the measures examined. However, the staff-to-bed ratio had a positive association with competitive employment. Higher follow-up rates were associated with poorer follow-up status on measures of substance abuse and total income. Thus the apparent improvement in clients' follow-up status over these five years reflected lower follow-up rates rather than true improvement.

Discussion

Over a five-year period, this study examined the status of veterans three months after discharge from an innovative residential work therapy program for veterans with severe substance use disorders. Although previous studies have examined factors that can influence health status after treatment (6), few studies have examined changes in performance in a large, multisite treatment program for an extended period (3). Measuring changes in clinical outcomes is of great importance in the evaluation of sustained health-system performance. After establishing that significant clinical improvements were observed in all domains three months after discharge from the CWTTR program, we evaluated simple linear trends and found significant reductions over the five years in staffing levels and follow-up rates. Nevertheless, we also found evidence of greater use of toxicology screens, increased attendance at self-help groups, and increasingly positive perceptions of the social climate of the residences. It is notable that these interventions do not require intensive staff resources and reflect greater reliance on technology, in the form of toxicology screens, and on self-help activities. We expected that sites with higher staffing ratios would have higher scores on COPES (8), but we did not find any significant relationships.

In our initial analysis of follow-up status, which adjusted only for baseline characteristics of the clients, we found two significant and positive trends that suggested increased sobriety and decreased psychological distress after discharge over the study period. However, once we adjusted our multivariate models for site-level changes in staffing levels and follow-up rates, we found that these temporal relationships were no longer statistically significant. Thus the apparent longitudinal gains reflected declining success in obtaining follow-up assessments, especially, it seems, among clients who were doing poorly. In the final analysis, which adjusted for both staffing levels and follow-up rates, no significant trends were found in the year of discharge, but higher levels of staffing were associated with better employment status.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the relationships between follow-up rates, staffing levels, treatment variables, and follow-up status are associational in nature and cannot be interpreted to demonstrate causality. Second, mental health status and substance use were assessed with self-report measures whose validity was not demonstrated. Also, the ASI is a relatively unsophisticated measure of psychiatric symptoms, although it accurately measures substance abuse. Finally, it would have been useful to have information on the reasons follow-up data were not collected and on the reasons for changes in program staffing or service delivery.

However, this study has both substantive and methodologic implications. Methodologically it demonstrates that sustained monitoring efforts after discharge can be used to demonstrate that client follow-up status is maintained through periods of major change. In addition, site-level data on staffing and follow-up rates can be used to expand the range of issues that are addressed. Although it is now widely recognized that observational follow-up data must be adjusted for the risks of differences in client characteristics at the time of program entry, this study demonstrates that additional adjustment for changes in the follow-up process may be necessary.

Conclusions

An important substantive finding of this study is that, contrary to clinical intuition, reduced staffing over the years, even to the substantial degree observed here, does not necessarily result in proportionate declines in clients' follow-up status. We found some evidence that programs adapted to reduced staffing levels by increasing technological monitoring through toxicology screens and encouraging the use of self-help services. We believe that a limit surely exists in which staff reductions would compromise the effectiveness of treatment, but we did not identify such a limit in this investigation. We did find that more intensively staffed programs had superior employment outcomes, an especially important finding in view of the emphasis on work restoration in this program.

Dr. Rosenheck is affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System, Northeast Program Evaluation Center (182), 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Seibyl is with the departments of psychiatry and public health at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

|

Table 1. Data on the Department of Veterans Affairs' Compensated Work Therapy/Transitional Residence program, by fiscal year

|

Table 2. Baseline characteristics, program participation, and discharge status of veterans who participated in the Compensated Work Therapy/Transitional Residence program, by whether or not they were interviewed at follow up

|

Table 3. Multiple regression of the relationship between treatment process measures and year-of-discharge and staffing among 1,771 veterans interviewed at follow up

|

Table 4. Multiple regression of the relationship between follow-up measures and year of discharge, staffing, and follow-up rate among 1,771 veterans interviewed at follow up

|

Table 5. Multiple regression of the relationship between follow-up measures and year of discharge, staffing, and follow-up rate among 1,771 veterans interviewed at follow up

1. Improving Mental Health Care: Commitment to Quality. Edited by Dickey B, Sederer L. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001Google Scholar

2. Greenberg G, Rosenheck RA: National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 2002 Report. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 2003Google Scholar

3. Rosenheck RA, Fontana A: Impact of efforts to reduce inpatient costs on clinical effectiveness: treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Medical Care 39:168–180, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Merrick EL, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, et al: Quality measurement and accountability for substance abuse and mental health services in managed care organizations. Medical Care 40:1238–1248, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Eisen SV, Wilcox M, Leff HS, et al: Assessing behavioral health outcomes in outpatient programs: reliability and validity of the BASIS-32. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:5–17, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Rosenheck R, Seibyl CL: Effectiveness of treatment elements in a residential-work therapy program for veterans with severe substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 48:928–935, 1997Link, Google Scholar

7. Rosenheck R, Seibyl CL: Participation and outcome in a residential treatment and work therapy program for addictive disorders: the effects of race. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1029–1034, 1998Link, Google Scholar

8. Moos R: Evaluation Treatment Environments. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1974Google Scholar

9. Moos R: Work Environment Scale Manual, 2nd ed. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1986Google Scholar

10. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW: Hierarchical Linear Models. Newbury Park, Calif Sage Publications, 1992Google Scholar

12. Singer J: Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 24:323–355, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar