Relationship Between Use of Psychiatric Services and Five-Year Alcohol and Drug Treatment Outcomes

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study was to examine the relationship between use of psychiatric services and alcohol and drug treatment outcomes five years after such treatment. It was anticipated that receipt of psychiatric services would predict long-term abstinence. METHODS: A sample of 604 outpatients from a managed care organization's chemical dependency program was interviewed about substance use and severity of psychiatric symptoms at baseline and at five years. Patients were required to have at least three years of membership in the health plan during the five years after intake. Severity of psychiatric symptoms was categorized as zero, low, middle, or high. Use of psychiatric services was ascertained on the basis of administrative data from the health plan. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between receipt of psychiatric services during the five years after intake and abstinence at five years. Results were adjusted for individual, treatment, and extra-treatment characteristics; severity of psychiatric symptoms at baseline; and other contacts with the health system. RESULTS: Patients who received a threshold level of psychiatric services (an average of at least 2.1 hours a year) were significantly more likely to be abstinent at five years than patients who received less than 2.1 hours a year. CONCLUSIONS: The use of psychiatric services among patients with chemical dependency is associated with enhanced long-term outcomes.

Co-occurring psychiatric problems are common among persons who enter alcohol and drug treatment, ranging from secondary symptoms of substance use disorders to primary conditions (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13). Outcome studies suggest that individuals with co-occurring problems fare less well in treatment (11,14,15).

Although the literature indicates that the provision of services that address patients' psychiatric problems improves short-term outcomes of substance abuse treatment (7,16,17,18,19,20,21,22), the effect of such services on long-term outcomes is less well understood. Several long-term studies have focused on patients with severe mental illness as well as alcohol and drug use disorders. However, these studies involved populations in the public mental health system (23,24) or college students (25) or had small samples of persons with alcohol or drug problems (23,24). An exception was a study of Irish inpatients, which showed that those who received psychiatric services during the year after initial inpatient treatment for alcoholism were more likely to be abstinent at their five-year follow-up (2,26). On the other hand, a study of men with chemical dependency in Department of Veterans Affairs medical settings found that receipt of outpatient psychiatric services was not associated with five-year outcomes, even among veterans with a diagnosed comorbid psychiatric illness (27).

We know of no studies that specifically addressed the role of use of psychiatric services in long-term alcohol and drug treatment outcomes in private managed care populations. Persons with substance use problems are costly consumers of health care (15,28,29), and services that improve outcomes may improve these patients' quality of life and benefit health plans financially. Health plans would like to know whether to invest in psychiatric services for patients who have chemical dependency as well as whether services would be effective for long-term members of the health plan.

Drawing on the literature of treatment trajectories (30,31,32,33,34,35), we examined the relationship between use of psychiatric services and five-year outcomes in the context of individual characteristics, treatment characteristics, and extra-treatment characteristics. Within these domains, our own previous research with this sample—the primary aim of which was to determine the relationship between short-term and long-term outcomes—showed that age, gender, motivation, dependence on only alcohol, treatment readmission, participation in 12-step programs, and having recovery-oriented social networks were significant predictors of long-term abstinence (36). Other researchers have found the following characteristics within these domains to be independent predictors of long-term improvement in alcohol and drug problems: female gender (37,38), older age, motivation (30), lower severity of psychiatric symptoms (37,39), treatment readmission and longer stays (30), participation in 12-step programs (40), and having recovery-oriented social networks (37,38,41).

Taking these known predictors into account, we used self-reported data and health plan administrative records to examine the association between psychiatric service use and five-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes in a managed care population. The sample had been admitted to a chemical dependency program and in the five years after intake had at least three years' membership in the health plan. This three-year requirement ensured that the sample was representative of persons who retained membership and also ensured that we had a sufficient period over which to capture information about psychiatric services.

Methods

Study sample

The study participants were adults who were admitted to the Kaiser Permanente Sacramento chemical dependency recovery program between April 1994 and April 1996. Northern California Kaiser Permanente is a large integrated health care delivery system that provides addiction and psychiatric services internally. Patients were offered random assignment to day treatment or a less intensive outpatient program. Research staff interviewed the patients by telephone six months, one year, and five years after intake. The pool of participants for the study reported here included all patients who were recruited at intake, whether or not they agreed to be randomly assigned or actually began treatment (N=1,204). We then selected those individuals who responded to the interview at five years, who provided responses to questions that were used as covariates in our model, and who had been members of Kaiser Permanente for at least three years between intake and five years (N=604). We examined data from the pretreatment evaluations and the five-year posttreatment interviews. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Kaiser Research Foundation Institute and the University of California, San Francisco. Written informed consent was also obtained.

Treatment programs

The original study assigned participants to a day hospital or a traditional outpatient program. The day hospital program provided four times the intensity of the outpatient program during the first three weeks, but services and program duration were the same; both programs were followed by five weeks of treatment of similar intensity. Aftercare consisted of one outpatient session a week for ten months. The philosophy of the program was based on total abstinence. Two staff psychiatrists were available to address psychiatric problems during treatment. More information about the original study has been reported elsewhere (15).

Measures

Outcome. The outcome measure was alcohol and drug abstinence for the previous 30 days, measured at the five-year follow-up.

Psychiatric services. Psychiatric services were defined as visits to the department of psychiatry or to one of the two staff psychiatrists from the chemical dependency recovery program. As a measure of intensity of service use, we used visit lengths from Kaiser Permanente databases (42) to calculate hours of psychiatric services per member year. We initially stratified the sample according to the amount of services patients received by collapsing hours of services per member year into four categories: zero, lowest one-third of nonzero distribution (range, .05 to <.7; mean=.4), middle one-third (range, .7 to <2.1; mean=1.3), and highest one-third (range, 2.1 to 34; mean=6.9). Bivariate analysis showed very little difference in abstinence between persons in the lowest three groups. Furthermore, it seemed unlikely that receipt of as few as two hours of services per year would affect long-term abstinence. We therefore dichotomized psychiatric service into two groups to be used in all analyses: at least 2.1 hours of service per year, and less than 2.1 hours of service per year.

Individual characteristics. Our conceptual model hypothesized that individual, treatment, and extra-treatment characteristics would be associated with change in substance use. Past studies of this treatment sample identified variables within these domains that were important predictors of abstinence (36). We included these variables, along with baseline psychiatric severity (described below), age, ethnicity, education, and income, in our multivariate model as covariates. Although abstinence at six months was also an important predictor of abstinence, we did not include that variable in this model, because it likely would have obfuscated the true impact of receipt of psychiatric services, given that receiving those services during the first six months could influence later abstinence.

We used questions from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Psychoactive Substance Dependence to ascertain a DSM-IV diagnosis for alcohol and drug dependency (11 substance types). For each substance, we established whether three of seven symptoms of dependency were present (15,43,44). Patients were categorized into one of four dependency types: alcohol only, drug only, alcohol and drug, and not dependent.

To assess severity of psychiatric symptoms at intake, we used the psychiatric composite score of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI). The ASI is a valid and reliable instrument (45) that examines severity of psychiatric symptoms and provides a score from 0 to 1, with higher scores designating greater severity. As we did in our previous study and consistent with work by other researchers (2,43,46), we stratified patients by collapsing psychiatric ASI scores into four categories: zero, lowest one-third of nonzero distribution (range, .001 to .406), middle one-third (range, .407 to .591), and highest one-third (range, .592 to 1).

Motivation was measured at intake by asking whether the patient identified abstinence as his or her treatment goal (44).

Treatment readmissions. Readmissions were identified from the Kaiser Permanente databases and self-reported data (for out-of-plan services) from the five-year interviews. Readmission within the health plan was defined as having at least three visits—with no more than a 30-day gap between each visit—to a chemical dependency program between one and five years after intake. This dichotomous measure indicated whether the person had a readmission.

Extra-treatment characteristics. At five years, we assessed the self-reported number of 12-step meetings attended in the previous year. Because 65 percent of persons attended no such meetings, the 12-step variable was dichotomized to reflect whether the person attended at least one meeting. To assess social support networks, respondents were asked the following questions: Among persons you talk to when you worry about personal problems, how many of these currently have a drug or alcohol problem? How many of your family members or friends have been actively supporting your efforts to reduce your drinking or drug use? How many of your family members or friends encourage you to drink or use drugs? We converted each of these measures into a dichotomous variable with 1 indicating at least one person and 0 indicating zero persons.

Nonpsychiatric, non-chemical dependency visits. Because the receipt of higher levels of psychiatric services might be a proxy for other contacts with the health system, and these other contacts may be strongly related to abstinence at five years, we extracted all office visits that were nonpsychiatric and not related to the chemical dependency recovery department (including emergency department visits) for the cohort and calculated the number of visits per member year for each patient. We included this continuous variable (range, 0 to 46; mean=6.7) in all multivariate models.

Data analysis

We used logistic regression to determine whether psychiatric services were associated with abstinence at the five-year interview. On the basis of our previous study (36), we adjusted for the following variables: gender, age, dependency type, whether abstinence was a goal at intake, readmission to a chemical dependency program, attendance at 12-step meetings in the previous year, and the three social support measures. We also adjusted for baseline severity of psychiatric symptoms, ethnicity, education, income, and number of office visits per member year that were nonpsychiatric and not related to the chemical dependency recovery program department. Other variables, including treatment type and randomization status, were not found to be independent predictors of five-year abstinence in the previous study (36).

Our primary analysis consisted of a logistic regression model with the dichotomous psychiatric services measure as the main independent variable. To determine whether the effect of receiving at least 2.1 hours of psychiatric service per year was different depending on the severity of psychiatric symptoms at baseline, we created a model that included the interaction of psychiatric services and severity of psychiatric symptoms.

Results

Patient characteristics

The study recruited 1,204 persons (92 percent of those entering the program); data for 589 persons were excluded from our analyses because these individuals had not been members of Kaiser Permanente for at least three of the five years after intake (N=443), did not respond to the five-year interview request (N=114), or had data missing on one of the model's covariates (N=43). The final cohort consisted of 604 persons averaging 57 months of Kaiser Permanente membership during the 60-month follow-up period. Compared with persons who were included in the study, those who were excluded were more likely to be men (70 percent compared with 65 percent), to be aged 17 to 29 years (29 percent compared with 18 percent), to have not completed high school (18 percent compared with 11 percent), to have had annual incomes of less than $40,000 (65 percent compared with 49 percent), and to have been dependent on drugs or drugs and alcohol rather than alcohol only (52 percent compared with 42 percent). We controlled for these variables in the multivariate analyses.

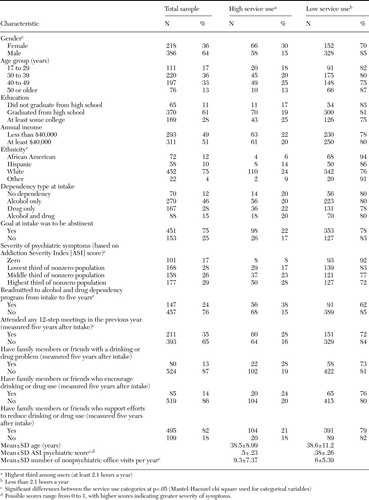

The mean±SD age of our sample was 39±9 years, and 36 percent were women (Table 1). A majority of the sample had completed high school (61 percent), had annual incomes greater than $40,000 (51 percent), and were white (75 percent). Nearly half were alcohol dependent only (46 percent), although many in this group used other substances. The most prevalent substances of dependence were alcohol (367 patients, or 61 percent), stimulants (140 patients, or 23 percent), marijuana (85 patients, or 14 percent), and cocaine (47 patients, or 8 percent). Among persons who were not dependent on any substance (N=70), 26 (37 percent) met criteria for alcohol or drug abuse. Seventy-five percent identified abstinence as their treatment goal. Twenty-four percent were readmitted to a chemical dependency program between one and five years after intake, and 35 percent had attended at least one 12-step meeting in the year before the five-year interview.

Persons who received at least 2.1 hours of psychiatric services per year accounted for 21 percent of the sample (N=124). In this group, the average person received 23 percent of services during the first year after intake, 22 percent during the second year, 20 percent during the third year, 15 percent during the fourth year, and 20 percent during the fifth year (data not shown). About 16 percent of psychiatric visits were to psychiatrists within the chemical dependency program and thus were made during initial treatment or a readmission.

In unadjusted analyses, women were more likely than men to receive the higher level (at least 2.1 hours) of psychiatric services, as were those who had a treatment readmission, and those who attended 12-step programs. Use of psychiatric services also differed among ethnic groups, with white individuals the most likely to receive the higher level. Severity of psychiatric symptoms at baseline was also highly correlated with the subsequent use of psychiatric services—the greater the initial severity, the more likely the patient was to be a high user of psychiatric services.

Unadjusted predictors of abstinence

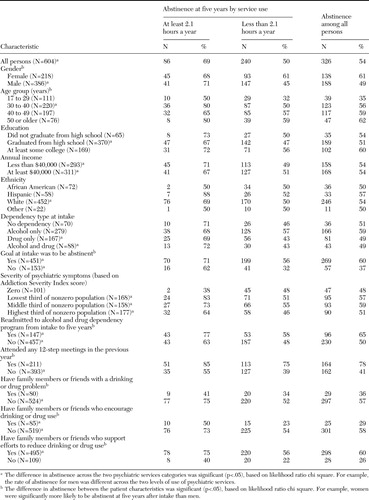

Table 2 shows the relationship between patient characteristics, use of psychiatric services, and 30-day abstinence at five years. The far right-hand column shows abstinence by patient characteristics regardless of receipt of psychiatric services. Among all persons in our sample, 54 percent reported abstinence for the 30 days before their five-year interview, and the rate of abstinence was highest for those who used the most psychiatric services (69 percent). Female gender, older age, and having abstinence as a goal at intake were also positively related to abstinence at five years, as was treatment readmission between one and five years, attendance at 12-step meetings, and the three social support variables.

Table 2 also shows the percentage of persons who were abstinent by level of psychiatric services and patient characteristics. For many patient characteristics, the relationship between greater use of psychiatric services and abstinence was significant, and, in every case but one, persons who received at least 2.1 hours of psychiatric services per year were more likely to be abstinent than those who received less than 2.1 hours. The one exception was among persons with a zero baseline ASI psychiatric score, but only eight persons in this group received the high level of psychiatric services.

Adjusted predictors of abstinence at five years

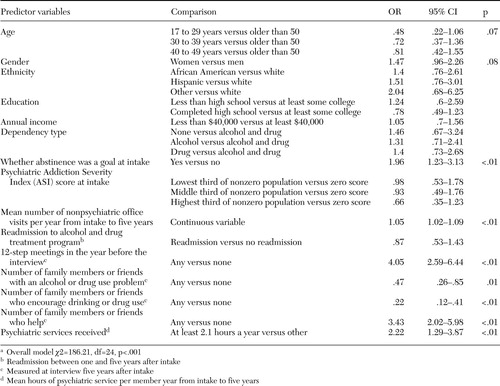

In adjusted analyses (Table 3), persons who received at least 2.1 hours of psychiatric services a year were more likely to be abstinent than those who received less than 2.1 hours. Other significant predictors of abstinence (at p=.05) were having abstinence as the goal of treatment, attending any 12-step meetings, and the three social support variables. A significant positive relationship was also observed between the number of health plan office visits (outside of the psychiatry and chemical dependency recovery program departments) and abstinence.

To determine whether the benefits of receiving the threshold level of psychiatric services were different depending on severity of psychiatric symptoms at baseline, we revised the model to include an interaction term between symptom severity and services. Including the interaction term did not improve the model fit, and the type 3 chi square for the interaction term was not significant. Thus we did not detect a statistically significant difference in the effect of use of psychiatric services among persons with different levels of severity of psychiatric symptoms at baseline. The one group that did not seem to benefit from receiving psychiatric services were those who had no psychiatric symptoms at baseline, but this result was not significant.

Discussion and conclusions

Providing services that address patients' addiction-related problems produces better short-term alcohol and drug treatment outcomes (17,19). The high rates of co-occurring psychiatric problems among individuals entering chemical dependency treatment (47) and the poor outcomes associated with co-occurring disorders argue for particular attention to the provision of psychiatric services.

We found that persons who received an average of more than two hours of psychiatric services per year during the five years after intake to chemical dependency treatment were more likely to be abstinent five years after intake. Receiving this threshold amount of psychiatric services was an important predictor of abstinence, independent of characteristics otherwise associated with outcomes, including gender, age, motivation, involvement in 12-step programs, social support, readmission to chemical dependency treatment, and other contacts with the health plan. Even among those who were not motivated at treatment intake—that is, those who did not have abstinence as their goal—receipt of the threshold level of psychiatric services was associated with abstinence. We did not find a difference in the effect of psychiatric services among persons with different levels of severity of psychiatric symptoms at baseline. It was encouraging to find that the group with the greatest severity also benefited from ongoing psychiatric services.

Psychiatric services may be an important component of a continuing-care model of treatment. Ongoing contacts offer providers an opportunity to note patients' potential for relapse. In addition, depression and other unresolved mental health problems might contribute to relapse. Analogously, our short-term findings indicate that ongoing receipt of medical services may help prevent relapse (43), and the findings of other research suggest that receipt of services in other problem areas, such as employment counseling and family therapy, would have similar effects (17).

A limitation of this study is that it was conducted in a private-sector managed care organization, and the results may not be generalizable to other health sectors. However, managed care is a major organizational model for public and private health care. Because we used the health plan's utilization data, the analysis was limited to patients who had at least three years' membership during the five years of follow-up. Thus the study findings are not generalizable to the entire baseline treatment sample. Nevertheless, our follow-up rate compares favorably with those of other studies, and, importantly, our method ensured a reliable measure of use of psychiatric services.

Finally, as with all observational studies, our results cannot be interpreted as causal. The relationship of threshold psychiatric services to abstinence may also be a result of the fact that those who receive such services are more connected to chemical dependency services or 12-step groups as well; however, we did control for chemical dependency readmissions and participation in 12-step programs.

As the addiction and mental health fields argue for a continuing-care service model, and mental health parity increasingly affects medical care, integrated and continuing chemical dependency and psychiatric care warrants a long-term intervention study. Although these data are observational, they suggest that adding psychiatric services to follow-up may be a better treatment model than usual care.

The authors are affiliated with the division of research of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2000 Broadway, Oakland, California 94612 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Weisner is also with the department of psychiatry of the University of California, San Francisco. Ms. Mertens is also with the department of psychiatry and mental health of the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

|

Table 1. Patient characteristics and use of psychiatric services among 604 persons who were admitted to an alcohol and drug treatment program between 1994 and 1996

|

Table 2. Abstinence from drug and alcohol use in the 30 days before a five-year follow-up interview, by patient characteristic and use of psychiatric services, among persons who were admitted to an alcohol and drug treatment program between 1994 and 1996

|

Table 3. Relationship between hours of psychiatric services received per member year during the five years after intake and odds of abstinence from drugs or alcohol in the past 30 days as reported five years after intake by 604 persons who were admitted to an alcohol and drug program between 1994 and 1996a

a Overall model χ2=186.21, df=24, p<.001

1. Drake RE, Mueser KT: Alcohol-use disorder and severe mental illness. Alcohol Health and Research World 20:87–93, 1996Google Scholar

2. McKay JR, Weiss RV: A review of temporal effects and outcome predictors in substance abuse treatment studies with long-term follow-ups: preliminary results and methodological issues. Evaluation Review 25:113–161, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Alterman AI, Cacciola JS: The antisocial personality disorder diagnosis in substance abusers: problems and issues. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179:401–409, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Helzer JE, Pryzbeck TR: The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 49:219–224, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hesselbrock MN: Gender comparison of antisocial personality disorder and depression in alcoholism. Journal of Substance Abuse 3:205–219, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Montoya ID, Atkinson J: Psychiatric diagnoses of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:43–51, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McLellan AT, Arndt IO, Metzger DS, et al: The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. JAMA 269:1953–1959, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: Predicting response to alcohol and drug abuse treatments: role of psychiatric severity. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:620–625, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Powell BJ, Penick EC, Nickel EJ, et al: Outcomes of co-morbid alcoholic men: a 1-year follow-up. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 16:131–138, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Haller DL, Knisely JS, Dawson KS, et al: Perinatal substance abusers: psychological and social characteristics. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:509–513, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rounsaville BJ, Dolinsky ZS, Babor TF, et al: Psychopathology as a predictor of treatment outcome in alcoholics. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:505–513, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Schuckit MA: The clinical implications of primary diagnostic groups among alcoholics. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:1043–1049, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Caetano R, Weisner C: The association between DSM-III-R alcohol dependence, psychological distress, and drug use. Addiction 90:351–359, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Moos RH, Brennan PL, Mertens JR: Diagnostic subgroups and predictors of one-year re-admission among late-middle-aged and older substance abuse patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 55:173–183, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Weisner C, Mertens J, Parthasarathy S, et al: The outcome and cost of alcohol and drug treatment in an HMO: day hospital versus traditional outpatient regimens. Health Services Research 35:791–812, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

16. Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Shifman RB: Do substance abuse patients with more psychopathology receive more treatment? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:576–582, 1993Google Scholar

17. McLellan AT, Weisner C: Achieving the public health and safety potential of substance abuse treatments: implications for patient referral, treatment "matching," and outcome evaluations, in Drug Policy and Human Nature: Psychological Perspectives on the Prevention, Management, and Treatment of Illicit Drug Abuse. Edited by Bickel WK, DeGrandpre RJ. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

18. McLellan AT, Hagan TA, Levine M, et al: Supplemental social services improve outcomes in public addiction treatment. Addiction 93:1489–1499, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, et al: One-year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence: delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:989–997, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Montoya ID, Svikis D, Marcus SC, et al: Psychiatric care of patients with depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:698–705, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Gonzalez G, Rosenheck RA: Outcomes and service use among homeless persons with serious mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 53:437–446, 2002Link, Google Scholar

22. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Clark RE, et al: The course, treatment, and outcome of substance disorder in persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:42–51, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Noordsy DL: Treatment of alcoholism among schizophrenic outpatients:4–year outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:328–329, 1993Google Scholar

24. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA: Long-term course of substance use disorders among patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:248–251, 1995Link, Google Scholar

25. Kwapil TR: A longitudinal study of drug and alcohol use by psychosis-prone and impulsive-nonconforming individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 105:114–123, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Patterson DG, Macpherson J, Brady NM: Community psychiatric nurse aftercare for alcoholics: a five-year follow-up study. Addiction 92:459–468, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ritsher JB, McKellar JD, Finney JW, et al: Psychiatric comorbidity, continuing care, and mutual help as predictors of five-year remission from substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 63:709–715, 2002Medline, Google Scholar

28. Edmunds M, Frank R, Hogan M, et al: Managing Managed Care: Quality Improvement in Behavioral Health. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1997Google Scholar

29. Parthasarathy S, Weisner CM, Hu T-W, et al: Association of outpatient alcohol and drug treatment with health care utilization and cost: revisiting the offset hypothesis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 62:89–97, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

30. Hser Y-I, Anglin MD, Grella C, et al: Drug treatment careers: a conceptual framework and existing research findings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 14:543–558, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Hser Y-I, Shen H, Chou C-P, et al: Analytic approaches for assessing long-term treatment effects: examples of empirical applications and findings. Evaluation Review 25:233–262, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Maddux JF, Desmond DP: Careers of Opioid Users. New York, Praeger, 1981Google Scholar

33. Simpson DD, Sells SB: Opioid Addiction and Treatment: A 12-Year Follow-Up. Malabar, Fla, Robert E Krieger, 1990Google Scholar

34. Booth BM, Yates WR, Petty F, et al: Patient factors predicting early alcohol-related readmissions for alcoholics: role of alcoholism severity and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 52:37–43, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Vaillant GE: The Natural History of Alcoholism Revisited. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1995Google Scholar

36. Weisner C, Ray GT, Mertens JR, et al: Short-term alcohol and drug treatment outcomes predict long-term outcome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 71:281–294, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Schutte KK, Byrne FE, Brennan PL, et al: Successful remission of late-life drinking problems: a 10-year follow-up. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 62:322–334, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Brennan PL, Moos RH: Late-life problem drinking: personal and environmental risk factors for 4-year functioning outcomes and treatment seeking. Journal of Substance Abuse 8:167–180, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM: A national 5-year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:538–544, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Timko C, Moos RH, Finney JW, et al: Long-term treatment careers and outcomes of previously untreated alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 60:437–447, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

41. Bond J, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C: The persistent influence of social networks and Alcoholics Anonymous on abstinence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 6:579–588, 2003Google Scholar

42. Selby JV: Linking automated databases for research in managed care settings. Annals of Internal Medicine 127:719–724, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Weisner C, Mertens J, Parthsarathy S, et al: Integrating primary medical care with addiction treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 286:1715–1723, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Mertens JR, Weisner CM: Predictors of substance abuse treatment retention among women and men in an HMO. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 24:1525–1533, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. McLellan TA, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:199–213, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Gottheil E, McLellan AT, Druley KA: Length of stay, patient severity, and treatment outcome: sample data from the field of alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 53:69–75, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

47. Compton WI, Cottler LB, Jacobs JL, et al: The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:890–895, 2003Link, Google Scholar