Perceived Reasons for Loss of Housing and Continued Homelessness Among Homeless Persons With Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study was to examine the reasons for the most recent loss of housing and for continued homelessness as perceived by homeless persons with mental illness. METHODS: A total of 2,974 currently homeless participants in the 1996 National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients (NSHAPC) were asked about the reasons for their most recent loss of housing and continued homelessness. The responses of participants who had mental illness, defined both broadly and narrowly, were compared with responses of those who were not mentally ill. The broad definition of mental illness was based on a set of criteria proposed by NSHAPC investigators. The narrow definition included past psychiatric hospitalization in addition to the NSHAPC criteria. RESULTS: A total of 1,620 participants (56 percent) met the broad definition of mental illness, and 639 (22 percent) met the narrow definition; 1,345 participants (44 percent) did not meet any of these criteria and were categorized as not having a mental illness. Few differences in reasons for the most recent loss of housing were noted between the participants with and without mental illness. Both groups attributed their continued homelessness mostly to insufficient income, unemployment, and lack of suitable housing. CONCLUSIONS: Homeless persons with mental illness mostly report the same reasons for loss of housing and continued homelessness as those who do not have a mental illness. This finding supports the view that structural solutions, such as wider availability of low-cost housing and income support, would reduce the risk of homelessness among persons with mental illness, as among other vulnerable social groups.

An increased risk of homelessness among persons with mental illness has been noted for many years (1). However, the reasons for this increase—and appropriate solutions to the problem—are still being debated (2,3,4). Some argue that vulnerability to homelessness in this group is the result of the symptoms of mental illness (3,5). Symptoms such as persecutory delusions, auditory hallucinations, bizarre behavior, and neglect of personal hygiene interfere with normal interpersonal relationships and cause conflicts with housemates and landlords. According to this view, mental illness represents a specific vulnerability factor for homelessness, and the reasons for homelessness among persons with mental illness are different from those in other groups.

Yet homeless persons with mental illness often attribute their housing problems to economic and social factors rather than to their psychiatric problems (6,7), a view that is also shared by some investigators (4,8). From this point of view, poverty, stigma, and limited job opportunities are at the root of homelessness among persons with mental illness, as they are in other vulnerable social groups. According to this view, mental illness represents a general vulnerability factor for homelessness, and the reasons for homelessness among persons with mental illness are mostly the same as in other groups (4).

These contrasting views have different implications for policy and service planning. The specific vulnerability hypothesis calls for more investment in psychiatric treatment of homeless persons who have mental illness (9) and for a linear or step-by-step housing program that requires treatment of psychiatric and substance use problems before independent housing is provided (10,11). The general vulnerability hypothesis, on the other hand, calls for the same structural solutions to the problem of homelessness for persons with mental illness as for other vulnerable groups (8,12), such as increasing the availability and accessibility of low-cost housing (13,14).

Better understanding of the reasons for loss of housing among persons with mental illness could inform this debate. If these individuals lose their housing because of a distinct set of factors related to symptoms of mental illness, such as disturbed behavior and interpersonal conflict, then the specific vulnerability hypothesis would be supported. However, if the immediate reasons for homelessness among persons with mental illness are mostly similar to those among non-mentally ill homeless persons, then the general vulnerability hypothesis would be supported.

The study reported here used data from the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients (NSHAPC) (15) to test these contrasting hypotheses. Two specific questions were addressed. First, how do the perceived reasons for the most recent loss of housing differ between persons who are mentally ill and those who are not? Second, how do the perceived reasons for continued homelessness differ between these two groups?

Methods

The NSHAPC methods have been described in detail elsewhere (15,16,17,18). Briefly, a nationally representative sample of more than 4,200 persons who used homeless services in 52 metropolitan and 24 nonmetropolitan areas in the United States between October 18 and November 14, 1996, was randomly selected and surveyed; the response rate was 96 percent. Services included emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, permanent housing programs for homeless persons, migrant workers' camps, centers for distribution of vouchers for shelter, soup kitchens, food pantries, drop-in centers, mobile food programs, and street outreach programs. Six to eight clients were interviewed in person during each of approximately 700 program visits. Semistructured interviews were conducted by trained Census Bureau field-workers. Each interview lasted about 45 minutes, and participants were paid $10 for their participation. NSHAPC was funded by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Participants

This article focuses on 2,974 currently homeless NSHAPC participants. Participants were rated as currently homeless if they reported staying in an emergency shelter, a transitional housing program, a hotel or motel paid for by a shelter voucher, an abandoned building, a place of business, a car or another vehicle, or any other nonresidential space on the day of the survey or during the seven-day period before being interviewed; reported that the last time they had a place of their own for at least 30 days in the same place was more than seven days ago; said that their last period of homelessness ended within the previous seven days; were identified for inclusion in the NSHAPC client survey at an emergency shelter or a transitional housing program, or at a voucher distribution program, but only if there was at least one other indicator of current homelessness; reported getting food from the shelter where they lived within the previous seven days; or reported staying in their own or someone else's place on the day of the interview but said they "could not sleep there for the next month without being asked to leave."

Assessments

Mental illness. Accurate diagnosis of mental illness in surveys of homeless populations is difficult (19,20,21). Following the suggestion of Susser and colleagues (20), two methods for defining mental illness were used in this study: a broad definition based on meeting the NSHAPC criteria for lifetime mental illness, used in previous NSHAPC reports (16,18), and a narrow definition that requires meeting the NSHAPC criteria for lifetime mental illness and a history of psychiatric hospitalization. NSHAPC criteria include scoring at least .25 on the psychiatric problems domain of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (22), ever having been treated for psychiatric problems, ever having taken prescribed medications for psychiatric problems, having any history of treatment and at least one ASI psychiatric problem, and having stayed in a psychiatric hospital or a group home for persons with mental illness. Meeting any of these criteria qualifies for the designation of mentally ill in the NSHAPC.

The NSHAPC criteria also include self-report of "a mental health condition" as the most important factor contributing to the individual's continued homelessness. However, because this study examined perceived reasons for continued homelessness among mentally ill persons, this criterion was not used for defining mental illness.

The ASI is a semistructured interview for assessing problems in seven domains—psychiatric, medical, legal, employment, family and social, illicit drug abuse, and alcohol abuse. Ratings on psychiatric problems, drug abuse, and alcohol abuse were used in this study. The psychometric properties of ASI ratings in various populations have been extensively studied and were generally found to be in the acceptable range (22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29). For example, in a sample of homeless persons, the alpha coefficients of internal consistency for ratings of psychiatric problems, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse were .89, .87, and .70, respectively (28). Also, ratings on these domains correlated strongly and specifically with other measures of each domain. For example, for psychiatric problems, the correlation coefficients with the Beck Depression Inventory (30) exceeded .50 and with the 90-Item Symptom Checklist (SCL-90) (31) exceeded .60.

Alcohol and drug abuse. Alcohol and drug abuse were rated on the basis of the NSHAPC criteria. Past-month alcohol abuse is ascertained by the NSHAPC when any of the following criteria are met: a score of at least .17 on the ASI alcohol abuse domain, treatment for alcohol abuse during the previous month, getting drunk at least three times a week during the previous month, and having any history of treatment and drinking at least three times a week during the previous month. Past-year and lifetime alcohol abuse were defined similarly by extending the time qualifiers. Persons who reported at least three alcohol-related difficulties during their lifetime from a list of eight difficulties adopted from the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) (32) were also categorized as having a lifetime alcohol problem.

Reasons for loss of housing and continued homelessness among currently homeless participants in the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients

Reason for most recent loss of housing

Financial problems

Couldn't pay the rent

Lost your job or the job ended

Rent increased and you couldn't afford to pay it

Someone who paid the rent or mortgage stopped paying it

Lost welfare or other cash assistance benefit

Not enough money for habitation

Interpersonal problems

You or your children were abused or beaten; violence in the household

Pushed out or kicked out

Didn't get along with people there

The people you were staying with asked you to leave

The landlord made you leave

Moved out because of a problematic relationship or the end of a relationship with a partner or relative

Had roommate or landlord problems

Health-related reasons

Went into a hospital or a treatment program

HIV, AIDS, or AIDS-related complex (ARC)

Was pregnant or had just had a baby

Became sick or disabled (other than ARC or AIDS related)

Drug or alcohol abuse

Was drinking

Was taking drugs

Miscellaneous reasons

Had a problem with the residence or the area in which the residence is located

Was displaced because the building was condemned, destroyed, or subject to urban renewal

The lease expired or the building was sold

Was looking for work or was forced to relocate to keep your current job

Had problems abiding by the rules of the current residence or program time ran out

Was released, dismissed, or discharged

Moved in with a significant other, a friend, or a relative

Death or illness in the family

Went to jail or prison

Went into the military

Left town

Needed a change of scenery or climate

Other reasons

Reason for continued homelessness

Insufficient income

Lack of employment

Lack of suitable housing

Drug or alcohol addiction

Insufficient education, skills, or training

Physical condition or disability

Mental health condition

Family or domestic instability

Insufficient services or lack of information about available services

Other reasons

Past-month drug abuse is ascertained by the NSHAPC when any of the following criteria are met: a score of at least .10 on the ASI drug abuse domain, treatment for drug abuse in the previous month, current intravenous drug use, and use of drugs at least three times a week during the previous month. Past-year and lifetime drug abuse were defined similarly by extending the time qualifiers. Individuals who reported having at least three drug-related difficulties during their lifetime from a list of eight that were adopted from the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) (33) were also rated as having a lifetime drug problem.

Medical conditions. Ratings of medical conditions were based on self-reports of diabetes, anemia, hypertension, heart disease or stroke, liver disease, arthritis, cancer, and HIV infection or AIDS.

Perceived reasons for loss of housing and homelessness. The study participants were asked about 32 reasons for leaving the last place of their own, such as a house, apartment, room, or other housing where they stayed for at least 30 days. They were then asked to identify which was the main reason. For this study, the responses were categorized by the author into five broad categories, described in the box on this page: financial problems, interpersonal problems, health-related reasons, drug and alcohol abuse, and miscellaneous reasons. Categorization of these items by a second mental health researcher who was blinded to the aims of the study and the author's original categorization produced very similar results (88 percent agreement, kappa=.83, p<.001). Respondents were also asked to select the most important reason for their continued homelessness from a list of ten reasons.

Statistical analysis

Two sets of analyses were conducted. First, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants with mental illness and those without mental illness were compared. Second, the perceived reasons for the most recent loss of housing and continued homelessness were compared among these two groups by using a series of binary logistic regressions in which mental illness was the dependent variable and the reasons for loss of housing and continued homelessness were the independent variables. Each category of reasons for loss of housing was rated dichotomously: 1 if a reason in that category was reported by the participant and 0 if not. Analyses adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics that had been found to be significantly different between groups in the first set of analyses.

Statistically significant logistic regression coefficients associated with any of the reasons for the most recent loss of housing or for continued homelessness would indicate significant differences between the study participants who were mentally ill and those who were not mentally ill on that reason or category of reasons. If individuals with mental illness lose their housing or remain homeless for a distinct set of reasons related to symptoms of mental illness, such as disturbed behavior and interpersonal conflict, the regression coefficients associated with these reasons would be statistically significant. In contrast, if the reasons for loss of housing and continued homelessness are similar between persons who are mentally ill and those who are not, few or none of the regression coefficients would be statistically significant.

Analyses were conducted once by using the broad definition of mental illness and another time by using the narrow definition. The comparison group of persons without mental illness for both analyses comprised the study participants who did not meet the broad criteria for mental illness.

Probability weights provided by the Census Bureau were used in all analyses to make percentages nationally representative. The complex sampling design of the NSHAPC requires adjustment using design elements (strata and primary sampling units). However, because of confidentiality concerns, these data are not made available. Instead, the Census Bureau recommended adjusting standard errors by using an approximation of the design effect (square root of 3) (18). All statistical tests reported in this article are thus adjusted. Analyses were conducted by using the logit routine of Stata 8.0 software (34) using probability weights provided by the NSHAPC.

Results

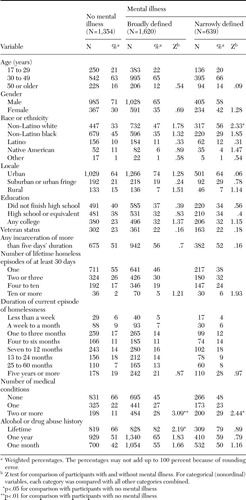

Overall, 1,620 (56 percent) of the 2,974 participants met the broad definition of mental illness, and 639 (22 percent) met the narrow definition. Few differences were noted between the group with mental illness and the comparison group of participants without mental illness (Table 1). Compared with those who were not mentally ill, participants who met the broad definition were more likely to have multiple medical conditions and lifetime alcohol or drug abuse; whereas participants who met the narrow definition were more likely to be non-Latino white and to have multiple medical conditions.

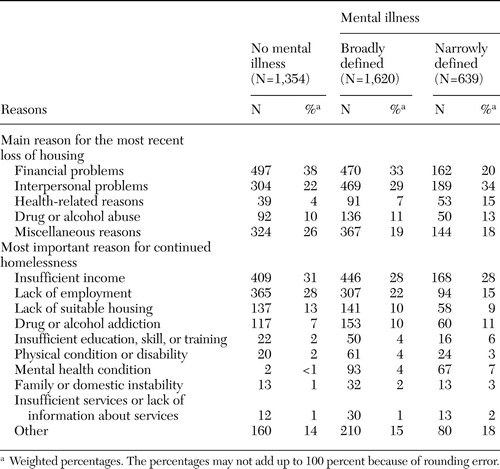

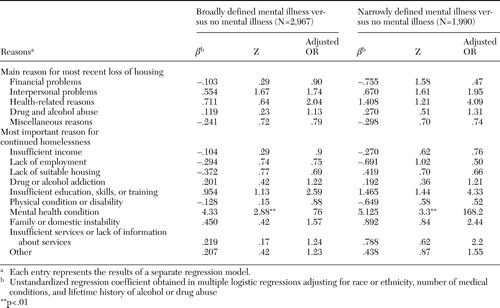

Few differences were noted between participants who were mentally ill, however defined, and those who were not mentally ill on the perceived reasons for loss of housing or continued homelessness (Tables 2 and 3). Financial and interpersonal problems were the most commonly perceived reasons for the most recent loss of housing and insufficient income, followed by unemployment and lack of suitable housing, the most common perceived reasons for continued homelessness. Although persons with mental illness were more likely than those without mental illness to give "a mental health condition" as the reason for continued homelessness, only 7 percent of those who met the narrow criteria and 4 percent of those who met the broad criteria for mental illness stated that reason.

Discussion

The findings of this study are constrained by a number of limitations. First, the data are based on self-report. Errors and biases in causal attribution are common with self-reported data, especially among individuals with severe mental disorders, who may lack insight into their illness and its social impact (35). To further explore this possibility, the perceived reasons for the most recent loss of housing were examined among participants who stated that mental illness was the main reason for their continued homelessness. Presumably, these individuals have more insight into the relationship between their illness and homelessness. However, even in this group, 28 percent reported financial problems as the major reason for the most recent loss of housing, 19 percent reported interpersonal problems, 12 percent reported health problems, and 17 percent reported alcohol and drug abuse. Nevertheless, reliance on self-report and lack of objective measures remain the major limitation of this study.

Second, the use of the same correction method for standard errors obtained in the different analyses might have inordinately reduced the power of some of the statistical tests. Thus the results of the statistical analyses should be viewed with caution. Third, the sampling frame of the NSHAPC included institutions that typically serve chronically homeless individuals. Furthermore, the NSHAPC was a prevalence survey. Persons with longer episodes of homelessness are overrepresented in prevalence samples. Thus the findings may not apply to the larger group of persons who experience only transient homelessness (36).

Despite these limitations, the NSHAPC data provide useful information about the chronically homeless persons who are the most vulnerable group in the homeless population. The perceived reasons for loss of housing and continued homelessness among persons with mental illness were mostly similar to the reasons reported by those without mental illness. Only a small fraction of the mentally ill individuals reported mental illness as the main reason for their continued homelessness. These findings support the general vulnerability hypothesis.

The findings are consistent with consumer surveys of homeless individuals with mental illness (7,37) in which the participants attribute their success or failure in obtaining and maintaining housing more to financial factors and housing availability than to mental illness and its treatment. The findings are also consistent with results of recent studies of risk factors of homelessness among persons with mental illness (12,38). Comparing homeless and nonhomeless individuals who had mental illness and those who did not, Sullivan and colleagues (12) concluded that mental illness does not represent a "distinctive pathway to homelessness," but rather an added disadvantage.

However, the findings are at odds with the results of a number of other studies (5,39) that showed a specific association between symptoms of mental illness and homelessness. These studies may have focused on individuals who had more severe illnesses, for whom mental health problems may be more significant determinants of housing instability (40). The divergent results of the studies may also be due to differences in raters' perspectives (41). Studies based on providers' assessment (5,39) often indicate a larger role for psychiatric factors than studies based on self-report (4,7,37).

Conclusions

Findings from this study support the general vulnerability hypothesis for loss of housing and continued homelessness among the homeless mentally ill. Treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders is only one of the needs of these individuals. To achieve housing stability, some mentally ill individuals may need assistance in obtaining public benefits. Others may need third-party money management (42), vocational assistance (43), and, on occasion, mediation to resolve emerging conflicts with housemates or landlords. These elements have been successfully implemented in case management programs designed specifically for homeless individuals with severe and persistent mental disorders (44). While anticipating implementation of such comprehensive case management programs in various health care and social agencies that serve the homeless mentally ill, these individuals could benefit from wider availability of low-cost housing, improved job opportunities, and income support programs (45)—the same structural initiatives that have been proposed to prevent homelessness in other vulnerable social groups.

The predominant service delivery models in many large urban areas make mental health and substance abuse treatment a prerequisite for housing placement. These service delivery models imply that mental illness is a specific vulnerability factor for homelessness. However, the results of this study support alternative service delivery models that do not distinguish between the housing needs of persons with and without mental illness and in which access to housing is not contingent on receipt of mental health or substance abuse treatment. The results of recent studies that compared these models further support the benefits of direct-access service models (46,14).

Dr. Mojtabai is affiliated with the department of psychiatry of Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City. Send correspondence to him at 10 Waterside Plaza, Apartment 5J, New York, New York 10010 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of currently homeless persons with and without a lifetime history of mental illness in the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients

|

Table 2. Perceived reasons for loss of housing and continued homelessness among currently homeless persons with and without a lifetime history of mental illness in the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients

|

Table 3. Results of logistic regression analysis of perceived reasons for loss of housing and continued homelessness among currently homeless persons with and without a lifetime history of mental illness in the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients

1. Susser E, Moore R, Link B: Risk factors for homelessness. Epidemiological Review 15:546–556, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, et al: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565–573, 2002Link, Google Scholar

3. Nelson SH: A second opinion. Psychiatric Services 53:573, 2002Link, Google Scholar

4. Cohen CI, Thompson KS: Homeless mentally ill or mentally ill homeless? American Journal of Psychiatry 149:816–823, 1992Google Scholar

5. Lamb HR, Lamb DM: Factors contributing to homelessness among the chronically and severely mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:301–305, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Roth D, Bean GJ Jr: New perspectives on homelessness: findings from a statewide epidemiological study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:712–719, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Tanzman B: An overview of surveys of mental health consumers' preferences for housing and support services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:450–455, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Mossman D, Perlin ML: Psychiatry and the homeless mentally ill: a reply to Dr Lamb. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:951–957, 1992Link, Google Scholar

9. Lamb HR: Will we save the homeless mentally ill? American Journal of Psychiatry 147:649–651, 1990Google Scholar

10. Outcasts on Main Street: Report of the Federal Task Force on Homelessness and Severe Mental Illness. DHHS pub ADM 92–1904. Washington, DC, Interagency Council on the Homeless, 1992Google Scholar

11. Korman H, Engster D, Milstein B: Housing as a tool of coercion, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

12. Sullivan G, Burnam A, Koegel P: Pathways to homelessness among the mentally ill. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:444–450, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF: Pathways to housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 51:487–493, 2000Link, Google Scholar

14. Metraux S, Marcus SC, Culhane DP: The New York-New York housing initiative and use of public shelters by persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:67–71, 2003Link, Google Scholar

15. US Department of Housing and Urban Development: Homelessness: Programs and the People They Serve: Summary. Dec 1999. Available at www.huduser.org/publications/homeless/homelessness/contents.htmlGoogle Scholar

16. US Department of Housing and Urban Development: Homelessness: Programs and the People They Serve: Technical Report. Dec 1999. Available at www.huduser.org/publications/homeless/homeless_tech.htmlGoogle Scholar

17. US Census Bureau: National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients (NSHAPC). Technical Documentation. March 2000. Available at www.census.gov/prod/www/nshapc/nshapc4b.htmlGoogle Scholar

18. Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS: Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA 285:200–206, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Robertson MJ: The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless, in Homelessness: A Prevention-Oriented Approach. Edited by Jahiel RI. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992Google Scholar

20. Susser E, Conover S, Struening EL: Problems of epidemiological method in assessing the type and extent of mental illness among homeless adults. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:261–265, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

21. Bellavia CW, Toro PA: Mental disorder among homeless and poor people: a comparison of assessment methods. Community Mental Health Journal 35:57–67, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:199–213, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al: New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 173:412–423, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Alterman AI, Brown LS, Zaballero A, et al: Interviewer severity ratings and composite scores of the ASI: a further look. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 34:201–209, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hodgins DC, El-Guebaly N: More data on the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity with the mentally ill substance abuser. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:197–201, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Cary KB, Cocco KM, Correia CJ: Reliability and validity of the Addiction Severity Index among outpatients with severe mental illness. Psychological Assessment 9:422–428, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Zanis DA, McLellan AT, Canaan RA, et al: Reliability and validity of the Addiction Severity Index with a homeless sample. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 11:541–548, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Argeriou M, McCarty D, Mulvey K, et al: Use of the Addiction Severity Index with homeless substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 11:359–365, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al: An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 4:53–63, 1961Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L: The SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 9:13–28, 1973Medline, Google Scholar

32. Moore R: The diagnosis of alcoholism in a psychiatric hospital: a trial of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST). American Journal of Psychiatry 128:1565–1569, 1972Link, Google Scholar

33. Skinner HA: The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behavior 7:363–371, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. StataCorp: Stata Release 8.0 User's Guide. College Station, Tex, 2003Google Scholar

35. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, et al: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:826–836, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Link BG, Susser E, Stueve A, et al: Lifetime and five-year prevalence of homelessness in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 84:1907–1912, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Crowded Out: Homelessness and the Elderly Poor. New York, Coalition for the Homeless, 1984Google Scholar

38. Odell SM, Commander MJ: Risk factors for homelessness among people with psychotic disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:396–401, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Gelberg L, Linn LS, Leake BD: Mental health, alcohol and drug use, and criminal history among homeless adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:191–196, 1988Link, Google Scholar

40. Clark C, Rich AR: Outcomes of homeless adults with mental illness in a housing program and in case management only. Psychiatric Services 54:78–83, 2003Link, Google Scholar

41. Rosenheck R, Lam JL: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381–386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

42. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al: Characteristics of third-party money management for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 54:1136–1141, 2003Link, Google Scholar

43. Min S-Y, Wong YLI, Rothbard AB: Outcomes of shelter use among homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:284–289, 2004Link, Google Scholar

44. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, et al: Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a 'critical time' intervention after discharge from a shelter. American Journal of Public Health 87:256–262, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Meyer IH, Schwartz S: Social issues as public health: promise and peril. American Journal of Public Health 90:1189–1191, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M: Housing first: consumer choice and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health 94:651–656, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar