Special Section on Relapse Prevention: Substance Abuse Relapse and Factors Associated With Relapse in an Inner-City Sample of Patients With Dual Diagnoses

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study documented rates of substance abuse relapse and explored factors associated with sustained remission among consumers with severe mental illness in a large, urban clinical sample. METHODS: Existing clinical records of consumers with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders who had achieved remission and who were interviewed at two or more subsequent follow-up points (12 months after remission) were reviewed. Consumers who relapsed within 12 months after remission were compared with those who maintained remission on demographic, clinical, and functional indicators. RESULTS: Of the 133 consumers who achieved remission, 91 (68 percent) had maintained remission at six-month follow-up, and 69 (52 percent) had maintained remission at 12-month follow-up. The strongest factors associated with maintenance of remission at 12 months were older age and living in Thresholds residential programs. Multivariate analysis showed that consumers who were older, held jobs, and lived in Thresholds residential programs at initial remission had a higher likelihood of maintaining remission at 12 months. To explore the potential impact of program dropout on the results, supplemental analyses using a third group without 12-month follow-up data were conducted. These analyses indicated that program dropouts were younger and less likely to live in Thresholds residential programs at initial remission. CONCLUSIONS: Age, therapeutic residential programming, and, to a lesser degree, employment appear to be potential factors to consider in the development of relapse prevention models.

Roughly half of consumers with severe mental illness experience co-occurring substance use disorders (1). Compared with consumers with severe mental illness alone, consumers with dual disorders typically exhibit poorer outcomes in a variety of domains—psychiatric relapse, hospitalization, suicide, incarceration, violence and victimization, physical health problems, quality of life, and homelessness (2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12). Consumers with dual disorders also have trouble engaging in traditional outpatient treatment, often because of the inherent difficulties in navigating sequential, parallel, or even contradictory mental health and substance abuse services (13). Fortunately, evidence-based models for integrated treatment programs have been developed and tested in a number of populations and settings over the past several decades. A review of 26 controlled studies indicates that integrated treatment approaches are superior to parallel treatment approaches for people with dual disorders (14).

Within integrated treatment, a number of structures and mechanisms have been shown to be effective in engaging and motivating consumers in their recovery. Effective integrated treatment usually is grounded in targeting the consumer's stage of readiness for clinical intervention. A substantial body of evidence supports the use of active engagement and outreach strategies for consumers in the early stages of treatment. Well-articulated models of case management, such as assertive community treatment, provide an integrated, multidisciplinary structure to engage consumers who might otherwise have difficulty linking with traditional, office-based services. For example, consumers who are served by high-fidelity assertive community treatment teams have shown greater reductions in substance use and increased rates of remission than consumers in lower-fidelity programs (15).

Likewise, motivational interventions have been adapted from the general substance abuse field (16) and applied successfully to consumers with severe mental illness as a method for increasing motivation to reduce or abstain from substance use (17,18). Ethnographers have also documented important factors that influence consumers' ability to reduce substance use: clinical relationships characterized by trust, meaningful activities, sober support networks, and stable housing (19).

Unfortunately, what remains unclear is what interventions are effective for consumers who have attained remission and need support to prevent relapse. A recent review of the literature for the general population detailed the cognitive-behavioral model of relapse prevention for substance use disorders (20). Many interventions within this model focus on intrapersonal determinants of relapse, such as self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, craving, motivation, coping, and emotional states. The cognitive-behavioral model also incorporates interpersonal determinants of relapse, such as social support. Within these approaches, a hallmark strategy of relapse prevention is to identify triggers for use and high-risk situations (21) and to prepare for such events or situations with coping mechanisms to prevent relapse—for example, relaxation to manage stress.

Some relapse prevention strategies involve lifestyle balance strategies that minimize the risk of relapse—for example, healthy eating and positive social relationships. Self-help approaches, such as 12-step programs, often emphasize social networks that reinforce positive aspects of sober living (22). Although these are excellent elements for building theory, a relapse prevention model for people with severe mental illness remains to be articulated. Another paper in this issue discusses the cognitive-behavioral models of relapse prevention and potential synthesis with neurobiological factors of relapse (23).

In the study reported here we aimed to document relapse rates and explore factors associated with relapse in a large urban rehabilitation agency by using an integrated treatment approach for consumers with dual disorders. Results from this clinical sample, although limited, can be combined with results from a more rigorously designed study of predictors of relapse in this special issue of Psychiatric Services (24) to contribute to the breadth of data sources available to generate preliminary hypotheses concerning relapse prevention for this population.

Methods

Overview and procedures

This study used archival clinical records in a naturalistic, between-group comparison of consumers who either relapsed or maintained remission after attaining initial remission from substance abuse in the program. The study compared records for each group on demographic, clinical, and other variables recorded as part of routine clinical care. Prospective clinician ratings of the severity of substance use disorder were recorded at six-month intervals and were used to classify consumers into the two groups.

Since 1998, Thresholds, a large psychiatric rehabilitation agency in Chicago, has implemented integrated dual disorders treatment with increasing model fidelity. In 1998 and 1999, Thresholds also implemented two residential treatment programs for consumers with dual disorders. Clinicians in these programs, and later in the agency as a whole, were trained to use validated scales to assess severity and treatment stages of substance use disorders to formulate stage-based interventions. These ratings also form a database for tracking consumers' substance use patterns in a large clinical sample. The substance use ratings of interest were isolated from a defined period beginning with the first use of standardized scale instructions in February 2000 until the cutoff point in July 2004.

The data set included consumers who entered Thresholds services at various points across the 54 months and who received services for varying durations. Because the study was approved by the Thresholds institutional review board as analysis of archival data collected for clinical and program evaluation purposes (and later deidentified after all pieces of the database were compiled), the institutional review board did not require written informed consent from consumers.

Individual records were selected for analysis if the consumer had active substance abuse or dependence, followed by a period of remission, and additional data for the patient were available for the subsequent six-month and 12-month follow-ups. Because of this required pattern, the sample represented only a subset of Thresholds consumers with dual disorders—that is, consumers who entered services in stable remission or who continued their substance abuse without remission were excluded. Because this study used clinical data, the initial comparison excluded consumers who dropped out of agency services before the requisite pattern was met. Supplemental analyses are presented by using dropouts as a third comparison group.

Participants

During the study period, 133 consumers met the study's criteria and were included in the main analyses. Most consumers were African American, male, and never married and had a high school education or more. A majority had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and substance dependence. Very few consumers in the sample were working at initial remission, and more than half lived in Thresholds housing (mostly dual disorders residential treatment).

Measures

Substance use ratings. The Alcohol Use Scale (AUS) and the Drug Use Scale (DUS) were designed to assess the severity of substance use disorder for this population (25,26). The Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS) was used to assess the consumer's stage of treatment progress (27). Clinicians were instructed to make ratings with these scales every six months (prompted by monthly reminders) with reference to the worst period of substance abuse in the previous six months and using multiple sources of information (for example, self-report, collateral reports, behavioral observations, and urinalysis results). Possible ratings on the AUS and DUS are 1, abstinence; 2, substance use without impairment; 3, substance abuse; 4, substance dependence; and 5, severe substance dependence. The eight possible ratings on the SATS are 1 or 2, engagement; 3 or 4, persuasion; 5 or 6, active treatment; and 7 or 8, relapse prevention. Previous research indicates high intraclass correlations for all scales: .94 for the AUS, .94 for the DUS, and .93 for the SATS (28).

To be included in the study, consumers had to receive either an AUS rating or a DUS rating of 3 or higher ("abuse"), followed by a rating period during which both AUS and DUS ratings were 2 or lower ("remission," inclusive of consumers' experiencing brief lapses without impairment during the previous six-month period). Coding abuse and remission in this manner has been established in previous research (15). The two subsequent rating periods (six and 12-month follow-ups) were coded in the same fashion to determine which consumers had relapsed or maintained remission. For 12-month relapse rates, consumers were coded as having relapsed if they scored 3 or higher on either the AUS or the DUS in either the six- or 12-month follow-up.

Demographic characteristics. Demographic data were obtained at intake and updated as the consumer's status changed, including age, gender, ethnicity, and marital status.

Functional indicators. Employment and educational attainment at initial remission were recorded for each consumer. Housing at initial remission was coded by comparing clinician-assigned residential codes, residential billing records, and, when unclear, consulting case notes or interviewing program staff for clarification. Housing codes were Thresholds housing, independent living, assisted or supported living, non-Thresholds supervised living, treatment institution, or homeless. There were four types of Thresholds housing: dual disorders residential treatment facilities, with 24-hour staffing and intensive, stage-based treatment focus; other non-dual disorders focused structured residential programs with 24-hour staffing; less structured residential settings with on-call staffing; and scattered homes or apartments with occasional staff support. Because exact dates of housing changes appeared to be recorded unreliably and were not discernable from case notes, tenure in housing was not computed. Functioning was assessed with the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (MCAS) (29,30), a community functioning measure that uses 17 items aggregated into four subscales with good interrater reliability: interference with functioning (.70), adjustment to living (.75), social competence (.75), and behavioral problems (.78).

Diagnoses. Psychiatric diagnoses were coded as schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder, bipolar disorder, other mood disorders, and other psychiatric disorders. Substance use diagnoses were coded as "abuse" if all disorders were labeled abuse and were coded as "dependence" if any were labeled dependence.

Data analysis

As described above, consumers in the study were coded into two groups based on AUS and DUS ratings: those who did not relapse (maintained remission for 12 months after initial remission) and those who relapsed (those who relapsed at some point within 12 months after initial remission). Statistical analyses using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences compared the two groups with use of t tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables. Binary logistic regression was used to analyze the impact of each significant variable (p value at or below .10, given the exploratory nature of these analyses), entered as a block in the regression analysis, in predicting sustained remission at 12-month follow-up. Additional analyses compared those who relapsed, those who did not relapse, and those who dropped out of the program.

Results

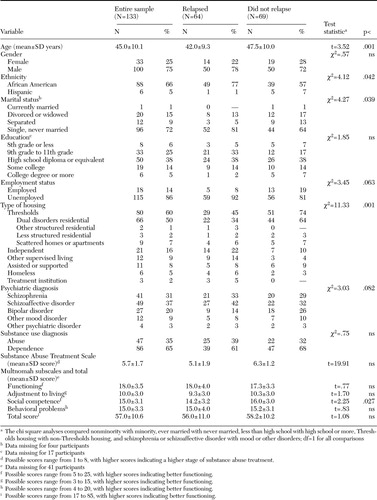

Of the 133 consumers who attained an initial remission, 91 (68 percent) had maintained remission at six-month follow-up, and 69 (52 percent) had maintained remission at 12-month follow-up. Table 1 compares the 69 consumers who maintained 12 months of remission with those who relapsed within 12 months on demographic, clinical, and other variables. Several demographic variables were associated with maintenance of remission, including older age, being white, and being married, widowed, divorced, or separated at initial remission. Living situation also was associated with maintenance of remission, with a greater percentage of the consumers who did not relapse living in Thresholds residential programs at initial remission. Employment at remission and having a psychiatric diagnosis other than schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were associated marginally with maintenance of remission. Gender, education, and type of substance use disorder were not significantly associated with remission.

Consumers who maintained remission also scored better on the MCAS social competence subscale than consumers who relapsed. No other differences were noted between the two groups on the MCAS. SATS scores are listed in Table 1 for descriptive purposes and, as expected, were significantly higher for consumers who did not relapse than for those who did relapse.

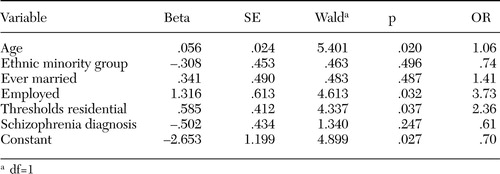

Using logistic regression, we explored the extent to which at least marginally significant variables predicted sustained remission. (Social competence was omitted because data were missing for 31 percent of the sample.) As can be seen in Table 2, older age, having a job, and living in a Thresholds residential program at initial remission were significant predictors of maintained remission. Consumers who held jobs at remission were almost four times as likely to have maintained remission at follow-up, and consumers who lived in Thresholds residential programs were more than two times as likely to have sustained remission. In this analysis, ethnicity, marital status, and psychiatric diagnosis did not predict maintenance of remission.

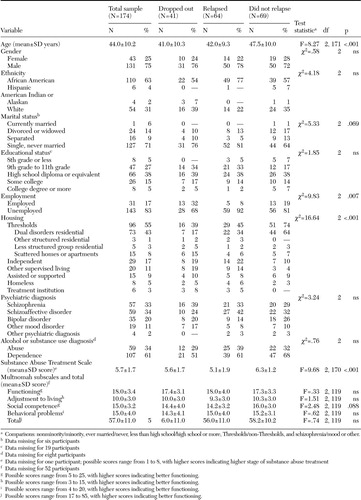

Because consumers who dropped out of the program were lost to follow-up in this sample, supplemental analyses were conducted to compare consumers who dropped out of the program (those who met entry criteria of abuse or dependence, followed by remission, but who dropped out before 12-month follow-up), those who relapsed, and those who did not. As can be seen in Table 3, those who dropped out were similar to those who relapsed in terms of younger age, being single, living outside Thresholds residential programs, and scoring lower on social competence. Effects for minority status and psychiatric diagnosis were lost in this comparison. Interestingly, those who dropped out were more likely to be employed at remission than those who relapsed and those who did not. Grouping those who dropped out with those who relapsed and comparing them with those who did not relapse produced similar results: effects for age, marital status, Thresholds residential programming, and social competence were in line with main analyses in both direction and strength of effect. Effects for minority status, psychiatric diagnosis, and unemployment on relapse were lost.

Discussion

After attaining initial remission, nearly one-third of the sample relapsed within six months, and nearly half the sample relapsed within one year, even while the participants were engaged in treatment. These rates of relapse are similar to those reported in other studies (24) and highlight the importance of developing relapse prevention strategies for this population.

Given this study's exploratory nature and limitations in terms of measurement issues and design (for example, inherent limitations with clinical records information, lack of intrapersonal variables in the data set, and limited information about those who dropped out of the program), the results should be viewed with caution. However, data from this clinical sample are a useful complement to data from more rigorous longitudinal studies of factors associated with relapse (24) that often omit consumers who choose not to participate in long research trials or do not meet strict study inclusion criteria. Each type of data presents inherent strengths and weaknesses in terms of internal and external validity. As a coherent theory for relapse prevention is developed, isolated findings from this particular study will be less important than the convergence of findings across a variety of studies, such as qualitative, experimental, and correlational studies.

For example, the demographic variable of younger age was associated strongly with relapse in this study and marginally associated with relapse in another study reported in this issue of Psychiatric Services (24). These findings are consistent with other research indicating attenuation of substance use disorders (31,32,33) and symptoms of schizophrenia (34) with age. From a stagewise, long-term perspective of substance abuse recovery, older consumers may have accumulated multiple opportunities over their lifetime to consider the benefits of sobriety or to practice relevant relapse prevention strategies, furthering their ability to maintain remission. Other demographic variables, such as ethnic minority status and being single, were associated with relapse in this study and typically are associated with poorer outcomes in substance use disorders (32,33).

Similar to the findings of Xie and colleagues (24) reported in this issue of the journal, consumers in this study who maintained remission were more likely to be living in Thresholds housing rather than in independent living environments, treatment institutions, or other supervised facilities. The vast majority of consumers in Thresholds housing lived in intensive dual disorders residential treatment programs (35). Supplemental analyses also indicated that consumers in Thresholds housing, particularly the dual disorders programs, were less likely to drop out of treatment.

Although our design prohibits causal inference, there could be several explanations for this finding that could be tested with more rigorous study designs. One possible explanation is that clinicians in the dual disorders residential programs have greater expertise and more time to focus on the treatment of dual disorders (staff caseloads in some programs average about six clients) than do clinicians in other programs. On the other hand, housing format could be a critical factor in the association. Most Thresholds housing is available on a long-term basis, with discharges supported and planned in close coordination with the consumer's needs and wants. Findings in this report are consistent with those of other studies indicating the effectiveness of long-term residential treatment with flexible entrance and exit mechanisms, compared with short-term residential treatment with more rigid rules and defined lengths of stay (36).

Despite being considered the highest level of functioning in the housing domain, independent living has been associated with poor outcomes in substance use disorders (37), including relapse (24). The reasons for this effect are unclear. One possibility is the unfortunate lack of housing options available to consumers with severe mental illness. In Chicago, many people with severe mental illness reside in areas noted for poverty, crime, and substance abuse. Living independently in these areas may offer fewer supports for sobriety compared with housing programs that offer built-in sober weekend activities, peer support, and professional counseling.

In ethnographic studies, social support is a critical element in reducing substance use (19). The results of this study corroborate the link between socialization and relapse prevention, because social competence was associated with sustained remission. Studies designed with more sophisticated measurement of social competence or social support may be better able to account for the impact of these factors on relapse, possibly as an intervening variable attenuating other results. For example, future studies might address whether consumers with strong social support show a greater likelihood of living independently without relapse.

Similarly, this study could not address whether rates of remission might be higher in nonresidential integrated dual disorders treatment programs (for example, assertive community treatment) that make concerted efforts to address the factors noted above (for example, social isolation and impoverished neighborhoods) in a supported housing approach, such as effective programs with these components in New York (38). Perhaps residential treatment programs are an "easier" alternative for structuring supportive relapse prevention environments than helping consumers acquire supports in their natural environments. More controlled studies are needed to address these questions and delineate clusters of consumers for whom one approach or the other is more effective. Other studies might also examine the effect of housing tenure on relapse prevention.

Although overall employment rates were low in this sample, having a job was associated with sustained remission in the main analyses. Ethnographic research has indicated that meaningful daily activity is a critical component in achieving abstinence for people with dual disorders (19). Combined with other evidence that employment has a role in preventing relapse (24), employment should be considered when interventions for relapse prevention are conceptualized.

Finally, there was some overlap between factors associated with relapse and factors associated with dropout (age, marital status, residential status, and social competence). However, employment was associated with dropout (opposite of findings for relapse). These results may indicate the complexities of program dropout in a clinical sample: that service dropout can denote a poor outcome (similar to relapse) or a positive transition to lower service needs (for example, gaining employment and recovering beyond the mental health program or to a less intensive service).

Conclusions

Because relapse is a common occurrence for people with dual disorders, researchers should identify and test relapse prevention strategies and interventions for this population. Age, therapeutic residential programming, and, to a lesser degree, employment appear to be factors to consider in the development of relapse prevention models. The data from this report alone should not be overinterpreted but, rather, should be included with other elements characterizing emerging relapse prevention models.

Dr. Rollins is affiliated with the Assertive Community Treatment Center of Indiana at Indiana University-Purdue University. Send correspondence to her c/o Roudebush VA Medical Center, 1481 West Tenth Street (11H), Indianapolis, Indiana 46202 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. O'Neill, Dr. Davis, and Mr. Devitt are affiliated with Thresholds in Chicago. This article is part of a special section on relapse prevention among persons with co-occurring substance abuse and other mental disorders. Robert E. Drake, M.D., Ph.D., served as guest editor of the section.

|

Table 1. Demographic, clinical, and other variables at initial remission among consumers with co-occurring disorders who relapsed at 12 months and those who did not

|

Table 2. Results of logistic regression of variables predicting sustained remission from substance abuse at one-year follow-up among 129 consumers with co-occurring disorders

|

Table 3. Characteristics at initial remission of consumers with co-occurring disorders by whether they relapsed at 12 months

1. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 264:2511–2518,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Swofford CD, Kasckow JW, Scheller-Gilkey G, et al: Substance use: a powerful predictor of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 20:145–151,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al: Predicting the "revolving door" phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856–861,1995Link, Google Scholar

4. Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT, et al: Prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders in persons making serious suicide attempts: a case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1009–1014,1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al.: Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 91:31–37,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dickey B, Azeni H: Persons with dual diagnoses of substance abuse and major mental illness: their excess costs of psychiatric care. American Journal of Public Health 86:973–977,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Bailey LG, Maxwell S, Brandabur MM: Substance abuse as a risk factor for tardive dyskinesia: a retrospective analysis of 1,027 patients. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 33:177–181,1997Medline, Google Scholar

8. Abram KM, Teplin LA: Co-occurring disorders among mentally ill jail detainees: implications for public policy. American Psychologist 46:1036–1045,1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Cuffel BJ, Heithoff KA, Lawson W: Correlates of patterns of substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:247–251,1993Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Goodman LA, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, et al: Physical and sexual assault history in women with serious mental illness: prevalence, correlates, treatment, and future research directions. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:685–696,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Drake RE, Mercer-McFadden C, Mueser KT, et al: Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:589–608,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Drake RE, Wallach MA: Substance abuse among the chronic mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1041–1046,1989Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Ridgely MS, Goldman HH, Willenbring M: Barriers to the care of persons with dual diagnoses: organizational and financing issues. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:123–132,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF, et al: A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:360–374,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Teague GB, et al: Fidelity to assertive community treatment and client outcomes in the New Hampshire dual disorders study. Psychiatric Services 50:818–824,1999Link, Google Scholar

16. Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, Guilford, 1991Google Scholar

17. Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, et al: The feasibility of enhancing psychiatric outpatients' readiness to change their substance use. Psychiatric Services 53:602–608,2002Link, Google Scholar

18. Carey KB, Purnine DM, Maisto SA, et al: Enhancing readiness-to-change substance abuse in persons with schizophrenia: a four-session motivation-based intervention. Behavior Modification 25:331–384,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Alverson H, Alverson M, Drake RE: An ethnographic study of the longitudinal course of substance abuse among people with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 36:557–569,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA: Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: that was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist 59:224–235,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Marlatt GA, George WH: Relapse prevention: introduction and overview of the model. British Journal of Addiction 79:261–273,1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Moos RH, Moos BS: Long-term influence of duration and frequency of participation in alcoholics anonymous on individuals with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 72:81–90,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. McGovern MP, Wrisley BR, Drake RE: Relapse of substance use disorder and its prevention among persons with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services 56:1270–1273,2005Link, Google Scholar

24. Xie H, McHugo GJ, Fox MB, et al: Substance abuse relapse in a ten-year prospective follow-up of clients with severe mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 56:1282–1287,2005Link, Google Scholar

25. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Clark RE, et al: Toolkit for Evaluating Substance Abuse in Persons With Severe Mental Illness. Cambridge, Mass, Evaluation Center at Human Services Research Institute, 1995Google Scholar

26. Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, et al: Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:57–67,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Burton HL, et al: A scale for assessing the stage of substance abuse treatment in persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:762–767,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Clark RE, et al: Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:201–215,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al: A community ability scale for chronically mentally ill consumers: I. reliability and validity. Community Mental Health Journal 30:363–383,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al: A community ability scale for chronically mentally ill consumers: II. applications. Community Mental Health Journal 30:459–472,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Warner LA, Kessler RC, Hughes M, et al: Prevalence and correlates of drug use and dependence in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:219–229,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Rosenberg SD, et al: Substance use disorder in hospitalized severely mentally ill psychiatric patients: prevalence, correlates, and subgroups. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:179–192,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Levinson DF, et al: Prevalence of substance abuse in schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:31–56,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Warner R: The Environment of Schizophrenia: Innovations in Practice, Policy, and Communications. Philadelphia, Taylor and Francis, 2000Google Scholar

35. McCoy ML, Devitt T, Clay R, et al: Gaining insight: who benefits from residential, integrated treatment for people with dual diagnoses? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:140–150,2003Google Scholar

36. Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Drake RE: A review of research on residential programs for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review 23:471–481,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Tolomiczenko GS, et al: Housing placement and subsequent days homeless among formerly homeless adults with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:674–679,1999Link, Google Scholar

38. Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF: Pathways to housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 51:487–493,2000Link, Google Scholar