Special Section on Relapse Prevention: Relapse of Substance Use Disorder and Its Prevention Among Persons With Co-occurring Disorders

Abstract

This article summarizes the scientific literature on the relapse process, describes the basic principles of relapse prevention treatment, highlights the major empirical studies, and offers suggestions for future research and application, especially in terms of ongoing care for persons with co-occurring disorders. Relapse prevention treatments have a well-established efficacy and effectiveness for persons with substance use disorders. Key ingredients include reducing exposure to substances, fostering motivation for abstinence, self-monitoring, recognizing and coping with cravings and negative affect, identifying thought processes with relapse potential, and deploying, if necessary, a crisis plan. Relapse prevention approaches may be best suited for persons in the action of maintenance stages of treatment or recovery. Further research is needed to examine relapse prevention therapies as a key component to continuing care for persons with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders.

The scientific approach to relapse of substance use can be credited to the early work of Brownell and colleagues (1) as well as Marlatt (2). Consistent with behavioral and cognitive-behavioral psychology, these authors carefully studied the relapse process, using the methods of functional analysis of the antecedents and consequences of substance use. This model articulated and studied relapse as a process, not simply an event or a "breakdown of willpower" (2).

On the basis of a number of studies of relapse antecedents, attempts to categorize them and develop predictive schemes, limitations to the original model of relapse have been identified (3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11). Among these are the nonlinearity of the true relapse process, limited emphasis on culture and context, and, perhaps most significantly, lack of attention to neurobiology, particularly the fundamental brain changes inherent in the addiction process (12,13,14,15). The most current relapse prevention model is less linear and hierarchical as well as more complex, developmental, recursive, and dynamic (16).

Core ingredients of relapse prevention therapy

Relapse prevention therapy as a specific intervention is one of a number of evidence-based practices for substance use disorders and now has a well-documented track record of producing positive outcomes (17,18,19). Recent reviews have shown relapse prevention therapy to be "empirically supported" (20) and evidence based (21). Relapse prevention therapy, a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy, consists of a number of key ingredients (22,23): reducing exposure to substances, fostering motivation for abstinence (decisional balancing of pros and cons of use and abstinence and processing ambivalence), self-monitoring (situations, settings, and states), recognizing and coping with cravings and negative affect, identifying thought processes with relapse potential, and deploying, if necessary, a crisis plan.

Aspects of relapse prevention therapy have evolved to become core ingredients in nearly all psychosocial treatments for substance use disorders, including traditional 12-step model rehabilitation programs (24). In an analysis of 24 randomized controlled trials of relapse prevention, Carroll (23) concluded that relapse prevention was an effective treatment for disorders related to nicotine, alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, and other drugs. Minimal differences in effectiveness were found across classes of substances. Compared with a control condition, relapse prevention demonstrated effectiveness approximately 50 percent of the time; more often than not, the effects were sustained at follow-up. Compared with alternative active psychotherapeutic treatments, relapse prevention results were comparable but not significantly better.

In a second review, Irvin and colleagues (25) conducted a meta-analysis of 26 relapse prevention therapy studies (total N=9,504). The overall treatment effect size was .14, with a relatively small 95 percent confidence interval (.10 to .17). For alcohol use, the effect size was .37; polysubstance use, .27; cocaine use (effect derived from only three studies), -.03; and tobacco smoking, .09. The finding of differential effects by substance was contrary to those in the earlier review by Carroll. Effect sizes were not significant for individual format (.10) compared with group treatment (.16) and for inpatient treatment (.11) compared with outpatient treatment (.16).

Application of relapse prevention therapy within a stagewise model

Relapse prevention approaches may be best suited for persons in the action or maintenance stages of treatment or recovery. In the action stage, the individual is exposed to a functional analysis of the antecedents to and consequences of his or her substance use. Personal knowledge about this process helps to enhance motivation and facilitate initial abstinence. In the maintenance stage, however, the individual has achieved some stability in his or her abstinence from substances and is focusing on lifestyle change and on dealing with changes in family and social relationships. The availability of ongoing professional care and monitoring is often less emphasized but remains important during this stage.

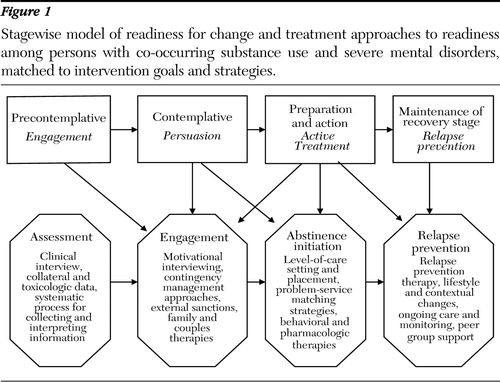

Within a context of the stagewise approach to continuing care, as shown in Figure 1, addiction treatment may be conceptualized in stages based on readiness for change. Indeed, assessment provides the basis for appropriate interventions at all stages. Therapeutic approaches can be aligned to readiness on the basis of assessment findings. Specific evidence-based practices are indicated at each of these stages (21). In other words, the therapeutic task varies according to the stage of treatment readiness (26,27).

For example, for persons at the precontemplative stage, motivational enhancement therapies or contingency management approaches promote therapeutic engagement, increased readiness, and movement toward the action stage. Offering active treatments (that is, those directed at achieving and stabilizing abstinence) at this juncture is premature, poorly received, and likely to be met with noncompliance (18). In contrast, persons at the action stage seek tools and skills to stop using substances and are motivated to receive such help. As with the reductionistic limitations to any linear model of human processes, including the newer model of relapse prevention (16), this stagewise model is, in reality, dynamic, recursive, and essentially chaotic. Nonetheless, it serves as a framework within which relational goals and treatment services may be organized.

The stagewise model for integrated dual diagnosis treatment (26) is highly consistent with the chronic disease model for addiction as developed by McLellan and associates (15). These authors noted that the traditional approach to both treatment of and research on addiction has been naively based on an acute condition paradigm. In this paradigm, a single episode of treatment is hypothetically required to "fix" a relatively circumscribed problem. It is as though a single course of treatment will result in long-term abstinence. In contrast, McLellan and associates compared the etiology, course, outcomes, and treatment compliance for substance use disorders with those for other chronic medical conditions, such as asthma, hypertension, and diabetes. The similarities are striking. In the case of substance use, both the clinical reality and longitudinal studies show that treatment duration, continuing care, and monitoring are likely to be associated with positive outcomes more than is the type or amount of the index treatment at the acute phase (15,28,29).

Evolving conceptions of relapse prevention services extend beyond the index episode and are conceptualized as ongoing routine care—much like an internist would monitor and treat expected variability in the blood pressure of a person with hypertension over the course of a long-term relationship (15). As part of ongoing positive lifestyle changes, the focus becomes recovery, not just remission. In fact, the self-help recovery model has long recognized this—for example, by emphasizing the benefits of service to others in securing one's own abstinence and improving quality of life (30). Likewise, for persons with chronic and persistent mental illness, developing a meaningful life becomes the larger ongoing goal that supports the proximate objective of symptom remission. These are in fact core principles of evidence-based practice in the areas of illness management and recovery (31,32).

Relapse prevention with co-occurring disorders

Within the stagewise model, during maintenance of the recovery stage for persons with substance use disorders, monitoring and treating co-occurring psychiatric disorders that are not substance related is clinically essential. Individuals who have more severe and persistent disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and severe mood disorders, should be receiving integrated treatments (26). The form and timing of treatments for disorders of the mild to moderately severe type, such as depression, anxiety, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and axis II disorders, are less certain, although these too will require ongoing monitoring and care (33).

In fact, few studies have specifically examined relapse prevention therapies for persons with substance use and other psychiatric disorders. Given that co-occurring psychiatric disorders are common among persons with substance use disorders, and these are typically associated with negative outcomes, this area of research remains critically important. A more complete review of this subject is provided in one of the other articles in this special section (34).

The rapidly developing research literature on integrated mental health and addiction treatment for persons with dual disorders has focused on the engagement and persuasion stages of the therapeutic relationship. The goals of these stages involve engaging clients in treatment and initiating abstinence rather than on the prevention of relapse to substance use. Longitudinal data about correlates of remission and recovery for persons with dual diagnoses have only recently become available, but no interventions have been formally tested during the maintenance stage (34). Three recent reviews found 26 controlled trials of integrated dual disorder treatments and verified the paucity of research during the maintenance phase of treatment (35,36,37).

One promising approach to integrated group therapy (as opposed to integrated treatment services) for relapse prevention was developed by Weiss and colleagues and is currently being tested in stage III effectiveness trials (38). This integrated group therapy focuses on relapse prevention skills for co-occurring substance use and bipolar disorders and addresses triggers and relapse risks for both disorders during the course of a structured manual-guided psychotherapy (39). However, studies of this approach focus only on symptom change and substance use associated with the index treatment (40).

In summary, no studies of relapse prevention therapies have been reported for the maintenance stage or within the context of ongoing or continuing professional care for persons with co-occurring disorders.

Conclusions

Relapse prevention treatments have well-established efficacy and effectiveness for persons with substance use disorders. As a generic approach, relapse prevention strategies are found in most treatments and services for persons with substance use disorders. Models of the relapse process have evolved from being purely cognitive-behavioral and linear toward a more dynamic interplay among dispositions, contexts, and past and current behaviors. The emergence of physiological measures and neuroimaging technology provide compelling neurobiological evidence for the nature of addiction and relapse as a process (41,42). Biological, social, and cultural factors, as well as the influence of other co-occurring psychiatric disorders, must now be key features to models and studies of the relapse to substance use and its prevention.

Relapse risk and protective factors associated with neurobiologic factors, management of psychiatric symptoms, and environmental and social contexts are important topics for future research for persons with co-occurring disorders. Relapse prevention therapy can be more broadly conceptualized and focused on lifestyle change and recovery rather than simple substance use or abstinence. Furthermore, relapse prevention therapies can easily be targeted to both the action and maintenance stages of treatment. This approach is highly consistent with the chronic disease model that recommends routine ongoing professional monitoring and continuing care for persons suffering from co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of Dartmouth Medical School, 2 Whipple Place, Suite 202, Lebanon, New Hampshire 03766 (e-mail, [email protected]). This article is part of a special section on relapse prevention among persons with co-occurring substance abuse and other mental disorders. Robert E. Drake, M.D., Ph.D., served as guest editor of the section.

Figure 1. Stagewise model of readiness for change and treatment approaches to readiness among persons with co-occurring substance use and severe mental disorders, matched to intervention goals and strategies.

1. Brownell KD, Marlatt GA, Lichtenstein E, et al: Understanding and preventing relapse. American Psychologist 41:765–782,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Marlatt GA, Gordon JR: Relapse Prevention. New York, Guilford, 1985Google Scholar

3. Lowman C, Allen J, Stout RL, and the Relapse Research Group: Replication and extension of Marlatt's taxonomy of relapse precipitants: overview of procedures and results. Addiction 91:S51-S71, 1996Google Scholar

4. Donovan DM: Assessment issues and domains in the prediction of relapse. Addiction 91:S29-S36, 1996Google Scholar

5. Kadden RM: Is Marlatt's relapse taxonomy reliable or valid? Addiction 91:S139-S145, 1996Google Scholar

6. Greenfield SF, Hufford MR, Vagge LM, et al: The relationship of self-efficacy expectancies to relapse among alcohol dependent men and women: a prospective study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 61:345–351,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cohen LM, McCarthy DM, Brown SA, et al: Negative affect combines with smoking outcome expectancies to predict smoking behavior over time. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 16:91–97,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM: Does urge to drink predict relapse after treatment? Alcohol Research and Health 23:225–232,1999Google Scholar

9. Rohsenow DJ, Niaura RS, Childress AR, et al: Cue reactivity in addictive behaviors: theoretical and treatment implications. International Journal of the Addictions 25:957–993,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, Guilford, 1991Google Scholar

11. Beattie MC, Longabaugh R: General and alcohol-specific social support following treatment. Addictive Behaviors 24:593–606,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kadden RM: Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatments for alcoholism: research opportunities. Addictive Behaviors 26:489–507,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Vastag B: Addiction poorly understood by clinicians: experts say attitudes, lack of knowledge hinder treatment. JAMA 290:1299–1303,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Margolis RD, Zweben JE: Treating Patients With Alcohol and Other Drug Problems: An Integrated Approach. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1998Google Scholar

15. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, et al: Drug dependence: a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA 284:1689–1695,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA: Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: that was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist 59:224–235,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Allsop S, Saunders B, Phillips M, et al: A trial of relapse prevention with severely dependent male problem drinkers. Addiction 92:61–74,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Chaney EF, O'Leary MR, Marlatt GA: Skill training with problem drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 46:1092–1104,1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. O'Farrell TJ, Choquette KA, Cutter HSG: Couples relapse prevention therapy after behavioral marital therapy for male alcoholics: outcomes during the first three years of starting treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 59:357–370,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. McCrady BS: Alcohol use disorders and the division 12 task force of the American Psychological Association. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 14:267–276,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. McGovern MP, Carroll KM: Evidence-based practices for substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 26:991–1010,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Carroll KM, Schottenfeld R: Nonpharmacologic approaches to substance abuse treatment. Medical Clinics of North America 81:927–944,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Carroll KM: Relapse prevention as a psychosocial treatment: a review of controlled clinical trials. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 4:46–54,1996Crossref, Google Scholar

24. McGovern MP, Fox TS, Xie H, et al: A survey of clinical practices and readiness to adopt evidence-based practices: dissemination research in an addiction treatment system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 26:305–312,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, et al: Efficacy of relapse prevention: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67:563–570,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Mueser KT, Noordsy DL, Drake RE, et al: Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

27. McHugo GS, Drake RE, Burton HL, et al: A scale for assessing the stage of substance abuse treatment in persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:762–767,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, et al: The effectiveness of telephone-based continuing care in the clinical management of alcohol and cocaine use disorders:12–month outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 72:967–979,2004Google Scholar

29. Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R: An experimental evaluation of recovery management checkups (RMC) for people with chronic substance use disorders. Evaluation and Program Planning 26:339–352,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Pagano ME, Friend KB, Tonigan JS, et al: Helping other alcoholics in Alcoholics Anonymous and drinking outcomes: findings from Project MATCH. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 65:766–773,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton D, et al: Illness management and recovery for severe mental illness: a review of the research. Psychiatric Services 53:1272–1284,2002Link, Google Scholar

32. Gingerich S, Mueser KT: Illness management and recovery, in Evidence-Based Mental Health Practice: A Textbook. Edited by Drake RE, Merrens MR, Lynde DW, New York, Norton, 2005Google Scholar

33. Cacciola, JS, Alterman AI, McKay JR, et al: Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with substance use disorders: do not forget axis II disorders. Psychiatric Annals 31:321–331,2001Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Drake RE, Wallach MA, McGovern MP: Future directions in preventing relapse to substance abuse among clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 56:1297–1302,2005Link, Google Scholar

35. Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Drake RE: A review of research on residential programs for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review, in pressGoogle Scholar

36. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF, et al: Review of treatments for persons with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:360–374,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Sigmon S, et al: Psychosocial interventions for adults with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders: a review of specific interventions. Journal of Dual Disorders, in pressGoogle Scholar

38. Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Greenfield SF, et al: Group therapy for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence: results of a pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:361–367,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Weiss RD, Najavits LM, Greenfield SF: A relapse prevention group for patients with bipolar and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 16:47–54,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Weiss RD: Treating patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence: lessons learned. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 27:307–312,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Leshner AI: Science-based views of drug addiction and its treatment. JAMA 282:1314–1316,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Cami J, Farre M: Mechanisms of disease, drug addiction. New England Journal of Medicine 349:975–986,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar