Special Section on Relapse Prevention: Substance Abuse Relapse in a Ten-Year Prospective Follow-up of Clients With Mental and Substance Use Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study addressed the rate and predictors of substance abuse relapse among clients with severe mental illness who had attained full remission from substance abuse. METHODS: In a ten-year prospective follow-up study of clients with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders, 169 clients who had attained full remission, defined according to DSM-III-R as at least six months without evidence of abuse or dependence, were identified. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve was developed to show the pattern of relapse, and a discrete-time survival analysis was used to identify predictors of relapse. RESULTS: Approximately one-third of clients who were in full remission relapsed in the first year, and two-thirds relapsed over the full follow-up period. Predictors of relapse included male sex, less than a high school education, living independently, and lack of continued substance abuse treatment. CONCLUSIONS: After attaining full remission, clients with severe mental disorders continue to be at risk of substance abuse relapse for many years. Relapse prevention efforts should concentrate on helping clients to continue with substance abuse treatment as well as on developing housing programs that promote recovery.

Substance use disorder, or substance abuse, is a chronic, relapsing illness. Cross-sectional studies of clients with dual diagnoses consistently show that their substance use disorders are often in remission (1,2,3,4,5,6). Although this finding could be taken as evidence of recovery from substance use disorder, prospective longitudinal studies—some of which are presented in this special section of Psychiatric Services—indicate that remission and relapse represent dynamic processes (5,6,7). That is, although many clients who enter outpatient mental health or dual disorder programs achieve full remission within months, most of these clients relapse to active substance abuse. For example, two separate prospective longitudinal follow-up studies (5,6) showed that the overall rate of active substance abuse did not change because as many individuals relapsed as achieved remission.

Because clients with dual disorders are highly prone to relapse of substance abuse, clinical and research attention should logically focus on the goal of relapse prevention. Yet we know remarkably little about this area. Several recent reviews of interventions for people with dual disorders note that existing studies emphasize engagement in treatment, motivation for remission, or initiation of remission rather than emphasizing relapse prevention (8,9,10).

To develop interventions and supports for relapse prevention, one critical step is to understand the timing and predictors of relapse (11). Thus the purpose of the study reported here was to analyze the pattern and predictors of substance abuse relapse in a ten-year prospective follow-up of clients with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders.

Methods

The New Hampshire Dual Diagnosis Study, which receives funds from federal and state sources, is a longitudinal, prospective follow-up of clients with dual diagnoses throughout New Hampshire. Participants in the study have been assessed yearly for more than ten years.

Participants

A total of 223 outpatients with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders began the longitudinal study between 1989 and 1992. The 223 original participants were predominantly male (166 participants, or 74 percent), Caucasian (215 participants, or 96 percent), young (mean±SD age of 34±8.5 years), and unmarried (199 participants, or 89 percent). In terms of diagnoses, 119 (53 percent) were given a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia, 50 (22 percent) a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and 54 (24 percent) a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. All had diagnoses of co-occurring substance use disorders; 166 (75 percent) had alcohol use disorder and 91 (42 percent) had drug use disorder. Cannabis was the most commonly abused drug, followed by cocaine. Other specific drugs were abused by fewer than 11 participants (5 percent). At baseline, the participants had high rates of recent hospitalization (121 participants, or 58 percent), homelessness (57 participants, or 26 percent), unemployment (204 participants, or 91 percent), and other manifestations of clinical and psychosocial instability. In all these respects, the study participants were similar to other clients with dual diagnoses in the New Hampshire mental health system at that time (12).

During ten years of follow-up, 46 participants (21 percent) were lost to attrition, 19 (9 percent) because they died and 27 (12 percent) because they dropped out of the study or could not be located. Thus 177 participants (86 percent of those still living) were actively participating in the study at ten years. Time trends for longitudinal outcomes were similar for the cohort of 177 and the cohort of 223, suggesting minimal bias due to attrition.

For the analysis reported here, we identified 169 participants who experienced a full remission from substance use disorder during the ten-year follow-up. As many participants as possible were followed in each subsequent year.

Procedures

Participants with dual disorders were recruited from seven of New Hampshire's ten comprehensive mental health centers through advertisements, public meetings, and clinical programs. The study was approved by the New Hampshire and Dartmouth institutional review boards. Participants gave written informed consent at baseline and continue to do so at yearly follow-ups. At baseline, participants were assessed by research psychiatrists to confirm that they met the study criteria of co-occurring severe mental illness (defined as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder plus long-term disability) and active substance use disorder (defined as abuse or dependence on alcohol or other drugs in the previous six months). Participants were then assessed in terms of symptoms, functional status, living situation, and quality of life by research interviewers. The same two interviewers reassessed the participants yearly for the ten-year follow-up. The participants were paid for their time and for providing a urine sample at each interview. Clinicians (case managers) also assessed the participants for substance use disorder yearly.

Measures

Research psychiatrists established co-occurring diagnoses of severe mental illness and substance use disorder by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (13). At baseline the research interview included items from the Uniform Client Data Inventory (14) to assess demographic information; the Time-Line Follow-Back (TLFB) (15) to assess the number of days of alcohol and drug use over the previous six months; the medical, legal, and substance use sections of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (16); detailed chronological assessment of housing history and institutional stays as determined by a self-report calendar supplemented by outpatient records and hospital records (17); the Quality of Life Interview (QOLI) (18) to assess objective and subjective dimensions of quality of life; the Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (19) to assess current psychiatric symptoms; and management information systems data and the Service Utilization Interview (20) to assess service use. In addition, we conducted urine toxicology screens in our laboratory by using EMIT enzyme immunoassay (Syva-Behring) to assess drugs of abuse. Follow-up interviews contained the same instruments, without reassessment of demographic and lifetime variables. Reliability on all scales was satisfactory, with intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from .94 to 1.00 for interrater reliability and from .41 to .94 for two-week test-retest reliability.

To supplement the substance abuse self-reports, clinicians (case managers) rated patients every six months on three rating scales: the Alcohol Use Scale (AUS), the Drug Use Scale (DUS), and the Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS). The AUS and the DUS are 5-point scales based on DSM-III-R criteria for severity of disorder: 1, abstinence; 2, use without impairment; 3, abuse; 4, dependence; and 5, severe dependence (2). The SATS (21) is an 8-point scale that rates progressive movement toward recovery from a substance use disorder according to Osher and Kofoed's (22) model of treatment and recovery: 1 and 2 represent the early and late stages of engagement, defined as developing a regular treatment relationship; 3 and 4 represent the stages of persuasion, defined as developing motivation for abstinence; 5 and 6 represent the stages of active treatment, defined as developing skills and supports for and achieving abstinence; and 7 and 8 represent the stages of relapse prevention, defined as developing skills and supports to maintain abstinence.

Self-report of substance use among persons with severe mental illness is problematic because of denial; minimization; failure to perceive that substance use disorder is related to poor adjustment; distortions due to cognitive, psychotic, and affective factors; and the inappropriateness of traditional measures for this population (23). Self-report data are therefore often supplemented with clinical ratings, laboratory measures, or multiple instruments to attain more valid assessments. In this study, a team of three independent raters considered all available data on substance use disorder (from the ASI, the TLFB, clinician ratings, and urine drug screens) to establish separate ratings on the AUS, the DUS, and the SATS. Our basic rule was that all three resources had to be consistent to establish a positive rating, such as remission (24). Thus any evidence of abuse or dependence was taken as an indicator of relapse. To determine the interrater reliabilities, researchers independently rated a randomly selected subgroup of 32 percent of the patients (433 observations of 65 patients). Intraclass correlation coefficients were high for all three scales: .94 on the AUS, .94 on the DUS, and .93 on the SATS.

Statistical analyses

To examine the distribution of relapse over time, we plotted a Kaplan-Meier survival curve (25). To predict duration of remission, we modeled survival analysis by using discrete-time survival analysis methods. Survival analysis is a technique for studying time to an event. However, because duration cannot be modeled directly, hazard or risk of an event of interest over time, which is a mathematical transformation of duration, is usually modeled (26).

The discrete-time survival model is a modified logistic regression in which hazard is defined as the conditional probability that an event will occur in a particular time interval given that it has not yet occurred (27,28). In our analysis, outcome is a logit hazard (logistic transformation of hazard) for relapse to occur. We examined several predictors, drawn from theory and empirical research: time to first full remission, sex, education, age, marital status, psychiatric diagnosis, type of substance abuse (alcohol, drug, or both), antisocial personality disorder, number of days of independent living, number of days living in a group home, frequency of contact with individuals who do not use substances, employment, and participation in outpatient substance abuse treatment (individual, group, or self-help). We considered relationships for which p was .05 or less to be significant and those for which p was between .05 and .10 to be marginally significant.

Results

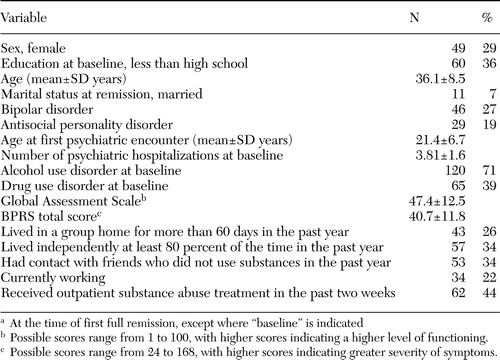

During the course of ten-year follow-up, 169 participants obtained at least one full remission of substance use disorder, according to the researchers' ratings described above and DSM-III-R criteria of at least six months without evidence of abuse or dependence. Because these assessments were done yearly, participants were in these first remissions for a period of six to 12 months. Characteristics of the 169 participants who attained full remission are summarized in Table 1. The data represent characteristics at the time of first full remission rather than at baseline for the larger study, because the date of the first full remission was used as the starting point for the survival analysis. Of the 169 participants who achieved remission, we had at least one year of follow-up data for 158.

Sustainability of remission

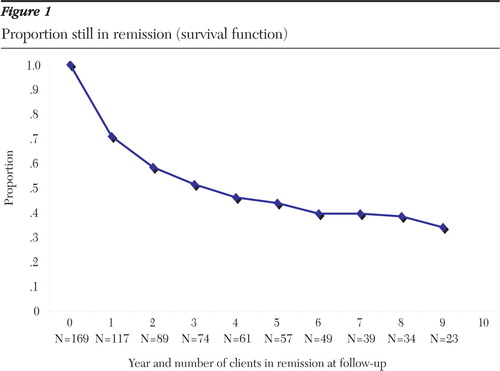

Figure 1 shows the proportion of clients with dual diagnoses who remained in full remission as a survival function. Relapse was especially common in the first year (almost one-third). By three years, approximately half had relapsed, and by nine years, more than two-thirds had relapsed. Because of these relapses as well as variable durations of follow-up and missing interviews, the number of remaining participants was lower at each assessment.

Predictors of duration of remission

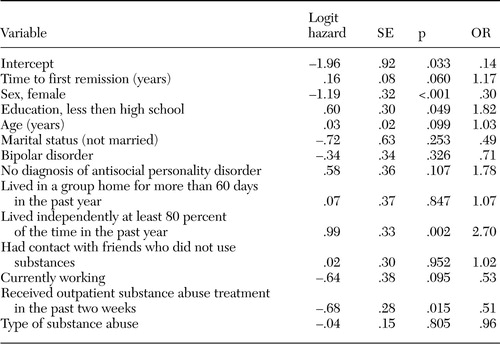

For the discrete-time survival analysis of first relapse, the number of participants was reduced to 128 because of missing data for several covariates. Table 2 shows several factors that predicted the hazard of relapse. Clients who were male, who had less education, who lived independently, and who did not participate in outpatient substance abuse treatment of some type were more likely to relapse. Longer time to first remission, older age, and lack of employment were marginally related to relapse. Type of mental illness, including co-occurring antisocial personality disorder, and type of substance use disorder (alcohol, other drugs, or both) did not predict relapse.

To understand the effect of predictors of relapse (sex, residential setting, and participation in outpatient substance abuse treatment), separate survival curves were plotted for each variable and for combinations of the three variables. The plots were consistent with the modeling results reported in Table 2, but several refinements were suggested. For example, the difference between living independently and not living independently was attenuated, which suggests that the effect on relapse is significant only when other variables are controlled for. The plots also suggested that there might be interactions among these covariates. For example, the difference due to residential setting appeared larger for females than for males. However intriguing these refinements may be, we reported only the main effect model, because the sample was not large enough for us to explore them rigorously.

Discussion

The primary finding of this study was that we confirmed the chronic, fluctuating nature of substance use disorder among people with severe mental illness. More than 75 percent of the study group achieved full remission of six to 12 months. However, relapse was also very likely, with the great majority of participants relapsing at some point, often within the first year of attaining full remission. Relapse became less likely over time, particularly after two years of remission.

The predictors of relapse suggest that some clients are more vulnerable to relapse than others: those who are males, those who take longer to achieve remission, those who have less education, those who are unemployed, those who live independently, and those who have not participated recently in substance abuse treatment. Time to remission may indicate more severe substance abuse, less internal capacity for remission, or fewer external supports for remission. The marginal relationship with employment suggests that having a constructive daily activity is a critical support, as many clients report (29). Similarly, clients who have less education may have fewer internal or external resources to help them sustain remission. Unemployment and low levels of education could also be markers for more severe neuropsychological deficits. Men with severe mental illness generally have worse outcomes than women (30), and men with co-occurring disorders also appear to do worse than women.

More interesting, because of their possibilities for intervention, are the findings related to living settings and ongoing substance abuse treatment. Living situation is of great interest, because housing is such a common problem for clients with co-occurring disorders. At this point, the literature shows that the great majority of persons with severe mental illness—perhaps 85 percent or more—do well in independent housing with supports, which is called supported housing (31,32). At the same time, this literature shows that clients with dual disorders tend to do poorly in supported housing programs. Our study confirms that these clients have difficulties in independent housing, even if they have already achieved full remission from their substance use disorders. The issue may be that these clients are forced by poverty and housing policies to live in high-risk neighborhoods, where they remain extremely vulnerable to substance abuse and other endemic problems. Research indicates that some clients are aware of the dangers of independent living in high-risk neighborhoods and seek out residential programs and other protective environments (33,34). Other active substance abusers seek out independent living and do poorly (35). More recently, a series of controlled studies established that clients with co-occurring disorders tend to do well in long-term residential programs (8). Clearly, there is a need to provide residential programs that foster recovery from substance abuse.

Continued involvement in substance abuse treatment has been identified many times as an important factor in stable remission, abstinence, and recovery (36,37,38,39). As McLellan (36) describes it, substance abuse is like other chronic illnesses in that people need treatment and other supports to manage their illnesses over a lifetime, not just during episodes of symptoms. Thus long-term involvement with self-help and treatment should be part of the expectation of care, just as it is for diabetes, hypertension, and many other chronic medical conditions. For clients with dual disorders, we need more information about what kinds of long-term treatments and supports are effective—for example, peer groups, dual recovery groups, case management, and family help.

One important caveat regarding housing and ongoing substance abuse treatment is that the relationships with outcomes could be circular. Clients who are more motivated to pursue and maintain abstinence may well seek residential protection and ongoing treatments. At the same time, those who are unmotivated, who relapse, or who otherwise falter may be expelled from these critical supports.

Several other caveats warrant attention. This study was conducted in a predominantly rural state, with relatively low availability of illicit drugs other than cannabis, with little racial and cultural diversity, with a relatively competent mental health system, and under other conditions that may have limited the generalizability of our results. Relapse was assessed yearly at six-month intervals, and some relapses may have been missed. Nevertheless, the study also has numerous strengths, including the high rate of long-term follow-up, the multimodal assessments of substance abuse, and the interdisciplinary research team. The results obtained here need to be tested among clients with dual diagnoses who are living in urban areas, where there are much higher rates of illicit drug use, racial diversity, and involvement with the criminal justice system (40).

Conclusions

This study provided several initial findings regarding factors that may enable clients with dual diagnoses to sustain remission from substance use disorders. Individuals who are amenable to intervention, such as employment, safe housing, and continued substance abuse treatment, should be considered for relapse prevention planning.

The authors are affiliated with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, 2 Whipple Place, Suite 202, Lebanon, New Hampshire 03766 (e-mail, [email protected]). This article is part of a special section on relapse prevention among persons with co-occurring substance abuse and other mental disorders. Robert E. Drake, M.D., Ph.D., served as guest editor of the section.

Figure 1. Proportion still in remission (survival function)

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 169 clients with substance abuse and mental disorders who attained remission from substance abusea

aAt the time of first full remission, except where "baseline" is indicated

|

Table 2. Discrete-time survival analysis model of hazard of the first relapse in a sample of 128 clients with substance abuse and mental disorders

1. Dixon L, McNary S, Lehman AF: Remission of substance use disorder among psychiatric inpatients with mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:239–243,1998Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, et al: Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:57–67,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Graham HL, Maslin J, Copello A, et al: Drug and alcohol problems amongst individuals with severe mental health problems in an inner city area of the UK. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:448–455,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, et al: Use of the AUDIT and the DAST-10 to identify alcohol and drug use disorders among adults with a severe and persistent mental illness. Psychological Assessment 12:186–192,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA: Long-term course of substance use disorders in severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:248–251,1995Link, Google Scholar

6. Cuffel BJ, Chase P: Remission and relapse of substance use disorder in schizophrenia: results from a one-year prospective study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:342–348,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Rollins AL, O'Neill SJ, Davis KE, et al: Substance abuse relapse and factors associated with relapse in an inner-city sample of patients with dual diagnoses. Psychiatric Services 56:1274–1281,2005Link, Google Scholar

8. Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Drake RE: A review of research on residential programs for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review 23:471–481,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette M, et al: A review of treatments for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:360–374,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Sigmon S, et al: Psychosocial interventions for adults with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders: a review of specific interventions. Journal of Dual Disorders 1:57–82,2005Google Scholar

11. Marlatt GA, Gordon JR: Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, Guilford, 1985Google Scholar

12. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Clark RE, et al: Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:201–215,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R-Patient Version (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1988Google Scholar

14. Tessler R, Goldman H: The Chronically Mentally Ill: Assessing Community Support Programs. Cambridge, Mass, Harper and Rowe, 1982Google Scholar

15. Sobell MB, Maisto SA, Sobell LC, et al: Developing a prototype for evaluating alcohol treatment effectiveness, in Evaluating Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Effectiveness. Edited by Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Ward E. New York, Pergamon, 1980Google Scholar

16. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O'Brien CP, et al: An improved diagnostic instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33,1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Clark RE, Ricketts SK, McHugo GJ: Measuring hospital use without claims: a comparison of patient and provider reports. Health Services Research 31:153–169,1996Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lehman AF: A Quality of Life Interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 51:51–62,1988Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J: Manual for expanded brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS). Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:594–602,1986Google Scholar

20. Clark R, Teague G, Ricketts S, et al: Measuring resource use in economic evaluations: determining the social costs of mental illness. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:32–41,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Burton HL, et al: A scale for assessing the stage of substance abuse treatment in persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:762–767,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Osher FC, Kofoed LL: Treatment of patients with psychiatric and psychoactive substance use disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1025–1030,1989Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Drake RE, Alterman AI, Rosenberg SR: Detection of substance use disorders in severely mentally ill patients. Community Mental Health Journal 29:175–192,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Drake RE, Mueser KT, McHugo GJ: Using clinician rating scales to assess substance use among persons with severe mental illness, in Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Edited by Sederer LI, Dickey B. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1995Google Scholar

25. Kaplan EL, Meier P: Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association 53:457–481,1958Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Willett J, Singer J: How long did it take? Using survival analysis in psychological research, in Best Methods for the Analysis of Change: Recent Advances, Unanswered Questions, Future Directions. Edited by Collins L. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1991Google Scholar

27. Singer J, Willett J: It's about time: using discrete-time survival analysis to study duration and the timing of events. Journal of Educational Statistics 18:155–195,1993Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Xie H, McHugo GJ, Sengupta A, et al: Using discrete-time survival analysis to examine patterns of remission from substance use disorder among persons with severe mental illness. Mental Health Services Research 5:55–64,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Alverson H, Alverson M, Drake RE: An ethnographic study of the longitudinal course of substance abuse among people with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 36:557–569,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Angermeyer MC, Kuhn L, Goldstein JM: Gender and the course of schizophrenia: differences in treated outcomes. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:293–307,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Newman SJ: Housing attributes and serious mental illness: implications for research and practice. Psychiatric Services 52:1309–1317,2001Link, Google Scholar

32. Rog DJ: The evidence on supported housing. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:334–344,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. McCoy ML, Devitt T, Clay R, et al: Gaining insight: who benefits from residential, integrated treatment for people with dual diagnoses? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:140–150,2003Google Scholar

34. Drake RE, Wallach MA: Mental patients' attraction to the hospital: correlates of living preference. Community Mental Health Journal 28:5–12,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Seidman LJ, et al: Self-report and observer measures of substance abuse among homeless mentally ill persons in the cross-section and over time. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 184:667–672,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, et al: Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness. JAMA 284:1689–1695,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Moos RH, Schaefer J, Andrassy J, et al: Outpatient mental health care, self-help groups, and patients' one-year treatment outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychology 57:273–287,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS: Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 11:294–307,1996Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Vaillant GE: Natural History of Alcoholism Revisited. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1995Google Scholar

40. Mueser KT, Essock SM, Drake RE, et al: Rural and urban differences in patients with a dual diagnosis. Schizophrenia Research 48:93–107,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar