The Health and Well-Being of Black Mothers Who Care for Their Adult Children With Schizophrenia

Abstract

This study compared the mental and physical health of two groups of black mothers aged 55 years and older: those who were providing care for their adult child with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (N=30) and those who did not have a child with mental illness (N=263). The only demographic variable that was found to differ between the two groups was that the women who were providing care for their adult child with mental illness had more children than the women in the comparison group. Both groups of women had similar mental health status. However, the mothers who were providing care for their adult children with mental illness had higher rates of chronic health conditions, such as high blood pressure, arthritis, and eye problems.

Research on black caregivers of adults with mental illness has tended to focus on whether the experiences of black caregivers differ from those of white caregivers (1,2). Findings from these studies indicate that black caregivers have better or similar emotional well-being compared with white caregivers, even though black caregivers tend to have socioeconomic disadvantages.

A growing body of literature has criticized efforts to understand the experiences of persons of color by comparing an ethnic minority group with a white majority group. The criticism arises because environmental and ecological circumstances may differ substantially between these two populations (3).

Thus understanding how black parents are affected by caring for an adult child with mental illness requires studies that compare these parents with black parents who do not have these atypical parenting responsibilities but who may face similar struggles related to racism, poverty, and difficulty obtaining resources. Furthermore, any examination of well-being among black caregivers should investigate physical as well as emotional health. The relationship of caregiver stress to physical health has been documented in studies of caregivers of persons with dementia (4). In addition, research shows that black women are significantly more likely than white women to have chronic health conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, and arthritis (5).

Our study compared the mental and physical health of older black mothers who were providing care for their adult children with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with that of a representative sample of older black women who did not have this family responsibility. Our primary research question was, How does the mental and physical health of black mothers who care for an adult child with schizophrenia compare with that of their peers in the general population? We hypothesized that because of the stress related to caring for a child with mental illness, mothers with this caregiving challenge would be more emotionally distressed and have more physical health problems than mothers who do not have a child with mental illness.

Methods

Participants included 30 older black women in Wisconsin urban areas with a son or daughter who had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and received publicly funded community support services. These mothers were recruited from 2000 to 2001 as part of a larger Wisconsin study on aging parents who care for an adult child with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, which was titled Aging Parents With a Mentally Ill Adult at Home. Mothers who participated in the schizophrenia study were 55 years or older and were providing ongoing assistance to their child with schizophrenia. All the adult children in the study were the biological offspring of the mothers, except for one child who was adopted.

A comparison group consisting of 263 older black women was drawn from wave 2 of the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH), which took place from 1992 to 1994 (6). The NSFH is a multistage, stratified probability sample of noninstitutionalized U.S. adults aged 19 years or older. So that the comparison sample would be comparable to that of the schizophrenia study, we selected black mothers aged 55 and over (N=280). Eleven women were excluded from our analysis because of missing data on health and well-being measures, and six women were excluded because they had an immediate family member or a household member with mental illness, resulting in a sample of 263 older black mothers who were not caring for a family member with mental illness. For both studies, informed consent and institutional review board approval were obtained.

The two groups of women did not differ in age, marital status, income, education level, or religious service attendance. The only significant difference found was that the women who were providing care for a son or daughter with schizophrenia had more children than the women in the comparison group.

We compared the two groups of women on mental and physical health outcomes. The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) measures how often 20 depressive symptoms occurred over the previous week and has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure (7). Although the full scale with the standard 4-point response categories (0, not at all, to 3, every five to seven days) was used in the schizophrenia study, the NSFH used a 12-item version that was developed by Ross and colleagues (8). In the 12-item version respondents give a count of the number of days during the past week that each of the 12 symptoms were present. Because of these differences in response categories, our study calculated a score of depressive symptoms by counting the number of depressive symptoms that were present during the past week. Only the 12 symptoms that were listed in the 12-item version were included in our analysis. Possible CES-D scores ranged from 0, indicating that the individual experienced none of the 12 symptoms during the past week, to 12, indicating that the individual experienced all 12 symptoms during the past week. Alpha reliability coefficients were .89 and .92 for the caregiver and NSFH samples, respectively.

Positive mental health was measured by items from three subscales—self-acceptance, personal growth, and purpose in life—from the multidimensional psychological well-being scale developed by Ryff (9). Five items that were selected from these three dimensions were common to both the NSFH and the schizophrenia studies. Each item was rated on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 6, strongly agree. Purpose in life was measured by a single item. Scores for self-acceptance and personal growth were derived by averaging the score on the two items for each subscale. Alcohol use was measured by a single item asking whether the respondent had consumed alcohol in the past 30 days; the item was coded as 1 for yes and 0 for no.

Self-reported health was measured by a single question that asked the mother to rate her health on a 4-point scale that ranged from 4, excellent, to 1, poor. Poor and fair health were collapsed into one category and coded as 0, and good and excellent health were collapsed and coded as 1. In both studies respondents were asked to list their medical problems. We included only medical problems that were common to both studies and reported those that were most frequently cited: high blood pressure, diabetes, arthritis, heart problems, and eye problems. These medical problems were constructed as separate variables, coded as 1 if the respondent reported having the condition and as 0 otherwise.

Analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted for comparisons of the mental and physical health outcomes between the two groups. Number of children, the only demographic variable on which the two groups differed, was entered as a covariate. For ease of interpretation, percentages are reported for dichotomous variables in Table 1. To perform the ANCOVAs, SPSS for Windows Release 11.0.1 was used. A power analysis determined that with our sample size we had .80 power to detect differences of half of a standard deviation, which Cohen (10) defines as a medium effect.

Results

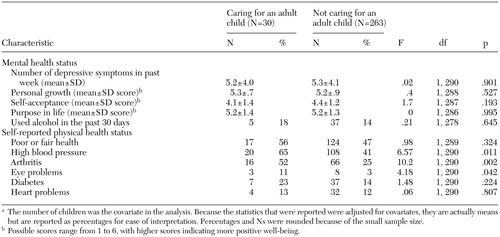

Contrary to our hypothesis, the two groups of women did not differ in any of the mental health variables, as shown in Table 1. Both groups reported experiencing approximately five depressive symptoms in the past week and had remarkably similar levels of positive mental health, as measured by feelings of personal growth, self-acceptance, and purpose in life. Both groups had low rates of alcohol use: 18 percent of mothers of adults with schizophrenia and 14 percent of mothers in the comparison group.

However, differences emerged when we examined indicators of the mothers' physical health. We found significant differences in self-reported chronic health conditions. Although both groups of mothers suffered from high rates of chronic health problems, mothers of adults with schizophrenia had significantly higher rates of high blood pressure, arthritis, and eye problems. Although the difference was not statistically significant, 56 percent (N=17) of the mothers of adults with schizophrenia reported their health as fair or poor, compared with 47 percent (N=122) in the comparison group.

Discussion and conclusions

Our findings indicate that black mothers who care for their adult children with schizophrenia may be emotionally resilient but physically vulnerable. These findings are significant, because previous studies on black caregivers of adults with mental illness have compared the emotional well-being of black caregivers with that of white caregivers. These studies may fail to detect the impact of caregiver stress on the well-being of black women, because these studies ignore a key aspect of black women's lives in which wide racial disparities are well known, namely physical health status.

Our analysis was limited because the schizophrenia study sample was a small convenience sample, which may not be representative of the population of black women who care for their adult children with mental illness, and may not have sufficient power to detect small effects. Also, because the comparison group was from a separate study, we cannot be sure that all the questions were asked in exactly the same way. In addition, self-reported health measures may not accurately measure actual health status. Furthermore, social support is a factor that is known to affect levels of stress among caregivers. Unfortunately, the two studies did not include parallel measures of social support, and thus this variable could not be included in our analysis.

Despite these limitations, our study provides preliminary evidence that black mothers who care for their adult children with schizophrenia may be vulnerable to physical health problems, which are already exhibited by black women at higher rates than in the general public (5). Future research on black caregivers needs to pay closer attention to the toll that caregiving may take on physical health.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01-MH-55928 from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH-55928) and by the Waisman Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The authors are affiliated with the department of social work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1500 Highland Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin 53705 (e-mail, [email protected]). A version of this paper was presented at the 2003 Society for Social Work and Research Conference, held January 16 to 19, 2003, in Washington, D.C.

|

Table 1. Mental and physical health status of black mothers aged 55 years and older, by whether or not they were providing care to an adult child with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disordera

a The number of children was the covariate in the analysis. Because the statistics that were reported were adjusted for covariates, they are actually means but are reported as percentages for ease of interpretation. Percentages and Ns were rounded because of the small sample size.

1. Picket S, Vraniak D, Cook J, et al: Strength in adversity: blacks bear burden better than whites. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice. 24:460–467, 1993Google Scholar

2. Steuve A, Vine P, Struening E: Perceived burden among caregivers of adults with serious mental illness: comparison of black, Hispanic, and white families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:199–209, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, et al: An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development 67:1891–1914, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hooker K, Bowman R, Coehlo D, et al: Behavioral change in persons with dementia: relationships with mental and physical health of caregivers. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 57:P453-P460, 2002Google Scholar

5. Williams D: Racial/ethnic variations in women's health: the social embeddedness of health. American Journal of Public Health 92:588–597, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Sweet J, Bumpass L: The National Survey of Families and Households—Waves 1 and 2: Data Description and Documentation. Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1996. Available at www.ssc.wisc.edu/nsfh/home.htmGoogle Scholar

7. Radloff L: The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385–401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Huber T: Dividing work, sharing work, and in between: marriage patterns and depression. American Sociological Review 48:809–823, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ryff C: Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57:1069–1081, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, Academic Press, 1977Google Scholar