Use of Psychiatric and Medical Health Care by Veterans With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

Risk behaviors and health care use among 396 initially hospitalized veterans with severe mental illnesses were examined. Health care use was abstracted from Veterans Affairs databases (March 1998 to June 2000) for one year after hospital discharge. Lifetime intravenous drug use was related to increased use of outpatient services, and current alcohol use was related to decreased health care use. Patients with posttraumatic stress disorder had greater use of medical outpatient services than patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, although they had longer hospital stays. These results highlight that veterans with severe mental illness receive more treatment in medical than psychiatric health clinics.

Understanding the relationship between health risk behaviors and health care use, including use of both medical and psychiatric services, among veterans with severe mental illness is becoming more important, because these persons are increasingly using the health care sector as their primary source of psychiatric care (1). For veterans, diagnoses of severe mental illness include schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). High rates of health risk behaviors are prevalent in this population (2) and may lead to increased use of health care services through associated medical illnesses. The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between specific health risk behaviors and use of health care services in a cohort of veterans with severe mental illness.

Methods

Veterans with severe mental illness were assessed for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk behaviors and infection (N=396) as part of a larger HIV seroprevalence and risk behaviors study. Participants were consecutive patients who were admitted to a Veterans Affairs (VA) inpatient psychiatric unit between March 1998 and June 2000 and who had a primary diagnosis of a severe mental illness, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or PTSD. Psychiatric diagnoses were based on a clinical interview, historical chart diagnosis, and consensus by two attending psychiatrists.

Health service use within the national VA health care system was abstracted from centralized VA databases for the one-year period after the initial hospital discharge. Use of outpatient health services was defined as VA clinic visits, which are encounters with a health care professional in a particular outpatient clinic. Use of outpatient health services was then classified into whether the care was medical or psychiatric (3). Our outcome variables for assessing VA health service use included the number of outpatient clinic visits and hospitalizations and the length of hospital stays over the 12 months after the initial hospital discharge.

We examined demographic factors, including race, marital status, age, living situation (independent or not), and service-connected disability, given their associations with health care use (4). Health risk behaviors included lifetime use of needles and crack cocaine, sexual risk behaviors, and current alcohol use disorder. Alcohol use was assessed by using the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (5), which exhibits high classification accuracy for alcohol use disorders among people with severe mental illness. Lifetime use of needles and crack cocaine and sexual risk behaviors were assessed with the AIDS Risk Interview (6), which reliably assesses behavior patterns associated with the risk of HIV infection among persons with severe mental illness.

To examine the relationships between HIV risk behaviors and patterns of health service use, negative binomial regression models were used. Each exponentiated negative binomial regression coefficient is an estimate of the incidence rate ratio. A logistic regression model was used to examine risks of rehospitalization over the follow-up year.

Results

Most veterans were living independently and had a disability related to military service. The veterans' mean age was 48 years; 61 percent were from ethnic minority groups, and schizophrenia-spectrum disorder was the most common diagnosis. High rates of lifetime health risk behaviors were observed: use of crack cocaine, current alcohol use disorder, history of needle use, and trading sex for drugs.

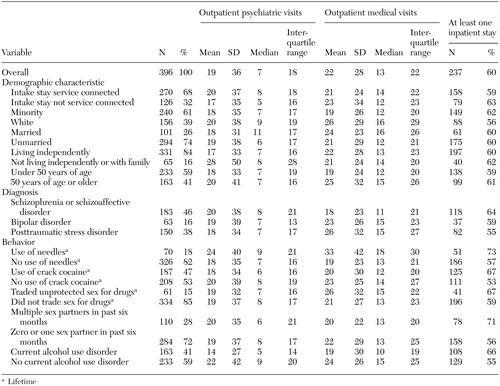

Table 1 summarizes health service use stratified by psychiatric and medical care. Overall, the median number of outpatient clinic visits was 24 during the follow-up year. Nearly half of the outpatient service use (7,476 out of 16,076 clinic visits, or 47 percent) was for psychiatric health care. However, the median number of psychiatric clinic visits was less than the median number of medical clinic visits (seven compared with 13, respectively). A total of 237 veterans (60 percent) were rehospitalized during the follow-up year, and the median length of inpatient stay was 16 days.

In multivariate analyses, lifetime intravenous needle use (incidence rate ratio=1.56, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.06 to 2.30) and having an inpatient visit during the year after discharge were related to greater use of outpatient psychiatric health services. Current alcohol use (incidence rate ratio=.56, CI=.41 to .75) and living in a noninstitutional setting (incidence rate ratio=.60, CI=.41 to .87) were related to less use of outpatient psychiatric health services. In multivariate analyses, lifetime use of needles (incidence rate ratio=1.61, CI=1.19 to 2.17) and unprotected sex in exchange for drugs (incidence rate ratio=1.44, CI=1.04 to 1.98) were both related to increased use of outpatient medical care. However, current alcohol use (incidence rate ratio=.72, CI=.57 to .91) was related to less use of outpatient medical services. Patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (incidence rate ratio=.68, CI=.53 to .87) had fewer nonpsychiatric visits than those with PTSD over the follow-up period. Rehospitalization during the one-year follow-up period was related to increased use of health services.

In a multivariate model, having multiple sex partners in the past six months (odds ratio=1.9, CI=1.11 to 3.25) and being older (odds ratio=1.03, CI=1.01 to 1.06) were related to being hospitalized. Veterans with service-connected disabilities, who were white, were older, were unmarried, or had a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder had longer hospitalizations.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the relationship of health risk behaviors to use of health care services in a cohort of veterans with severe mental illness by using objective measures of use of VA health care services. Lifetime intravenous drug use was related to increased use of outpatient services, whereas current alcohol use was related to decreased use of outpatient services. Veterans with PTSD had more outpatient use of medical services over the follow-up year than veterans with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. In contrast, veterans with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders had higher rates of rehospitalization and longer stays than veterans with PTSD.

The high rate of use of psychiatric services in this cohort is consistent with reports of a high proportion of VA health services being devoted to psychiatric care. More than half of all veterans who are service connected for a severe mental illness use the VA as their primary source of mental health care (7). Veterans with severe mental illness are also high users of VA medical services. Overall, this cohort was more likely to use medical services (53 percent of clinic visits) than psychiatric services. Paralleling recent health care shifts from inpatient to outpatient services, the numbers of veterans receiving outpatient health services has increased. Although not examined in this study, high rates of comorbid medical conditions reported for individuals with severe mental illness may account for the high rates of medical service use that we observed (8).

High rates of health risk behaviors (for example, drug use) observed in this cohort of veterans with severe mental illness likely contributed to the high rates of use of medical services. For example, lifetime intravenous drug use was related to overall use of outpatient health services, which likely reflects the long-term health risks of intravenous drug use and associated comorbid medical conditions. In contrast, current alcohol users were less likely to receive health care than those who did not use alcohol; additional research is warranted to further explore the reasons for this relationship. It is important to consider that this cohort of veterans had been discharged from the hospital at study enrollment, which limits generalizability of the findings.

As the VA strives to provide cost-efficient health care to veterans with severe mental illness, understanding veterans' patterns of VA health service use and the relationship of health risk behaviors to illness and use of medical and psychiatric services is crucial. The high rates of health risk behaviors we observed—and related health care use—may provide an opportunity for educational efforts targeting healthier lifestyles for veterans with severe mental illness.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Cooperative Studies Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, through grant CSP#706D and a research career award to Dr. Butterfield (RCD-0019-2). Dr. Bosworth was supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration Health Services Research and Development Service through an investigator-initiated award (20-034).

The authors are affiliated with Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center in North Carolina. Dr. Bosworth, Dr. Calhoun, and Dr. Butterfield are also with the department of psychiatry at Duke University in Durham. Address correspondence to Dr. Bosworth at the Center for Health Services Research in Primary Care, Building 16, Room 70, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center (152), 508 Fulton Street, Durham, North Carolina 27705 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Service use by veterans with severe mental illness during the 12 months after inpatient discharge, March 1998 to June 2000

1. Calhoun PS, Bosworth HB, Grambow SC, et al: Medical service utilization by veterans seeking help for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:2081–2086, 2002Link, Google Scholar

2. Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, et al: Prevalence and correlates of sexual activity and HIV-related risk behavior among psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69:846–850, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Beattie M, Swindle RW, Tomko LA: Department of Veterans Affairs Databases Resource Guide, Vol 3: Patient Treatment File. Palo Alto, Calif, Health Services Research and Development Service Center for Health Care Evaluation, 1992Google Scholar

4. McQuillan G, Coleman PJ, Kurszon-Moran D, et al: Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1976 through 1994. American Journal of Public Health 89:14–18, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rosenberg S, Drake RE, Wolford GL, et al: Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI): a substance use disorder screen for people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:232–238, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Chawarski MC, Pakes J, Schottenfeld RS: Assessment of HIV risk. Journal of Addictive Diseases 17:49–59, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Rosenheck R, Greenberg G: Department of Veterans Affairs National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 2001 Report. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2002Google Scholar

8. Coulehan J, Schulberg HC, Block HR, et al: Medical comorbidity of major depressive disorder in a primary medical practice. Archives of Internal Medicine 150:2362–2367, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar