Psychiatrists' Attitudes About and Informed Consent Practices for Antipsychotics and Tardive Dyskinesia

Abstract

This study provided representative data about the attitudes and behaviors of psychiatrists with respect to obtaining informed consent for antipsychotic medications. A cross-sectional representative survey of 617 psychiatrists, stratified by age and gender, was conducted by using a self-report questionnaire. The response rate was 72 percent (N=427). Demographic characteristics did not correlate with whether the respondents disclosed information about the potential side effect of tardive dyskinesia, which is associated with antipsychotic medications. Respondents' attitudes toward informed consent were a strong predictor of whether they disclosed information about antipsychotic medications and the risk of tardive dyskinesia. A total of 263 respondents (78 percent) routinely disclosed information about tardive dyskinesia.

A patient's right to consent to or refuse treatment is ethically and legally fundamental and reflects respect for the patient's autonomy (1). To assist patients in making a treatment decision, psychiatrists should provide information about the nature, benefits, and risks of proposed treatments as well as information about alternative treatments, including the option of not having treatment (1,2). Informed consent is the common law standard in Canada and the United States (1,3). In Ontario, legislation codifying the common law standard on informed consent came into effect in 1995 (2). Informing patients who are being treated with a conventional antipsychotic medication about tardive dyskinesia is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association (4). However, studies reveal that only 32 to 67 percent of psychiatrists routinely follow this recommendation (5,6,7).

Our study sought representative data about psychiatrists' attitudes toward informed consent for antipsychotic medications and whether psychiatrists disclosed information about the benefits and risks of antipsychotic medications and the risk of tardive dyskinesia. We hypothesized that psychiatrists would disclose more if they were younger than age 40 or female. Our study was planned before codification of the common law standards on informed consent but was conducted shortly after codification. The effect of conducting our study after codification was addressed by asking psychiatrists whether their disclosure practices had changed after codification.

Methods

In 1996 a total of 1,643 psychiatrists were licensed to practice medicine in Ontario, Canada. A random sample of psychiatrists—stratified by age (40 years and older and younger than 40 years) and gender—was obtained from the provincial medical licensing body. Questionnaires were mailed to this sample: 164 men and 146 women aged 40 years and older and 161 men and 146 women aged 40 years and younger. A cover letter enclosed in the mailing explained the survey. The survey involved an initial mailing followed by two mailings to nonrespondents and a telephone reminder before the last mailing. Respondents were tracked through a separately returned identification card. Questionnaires were completed anonymously. The research ethics board of the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, now known as the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, approved the study, and consent was implied by the completion and return of the questionnaire.

The self-report questionnaire assessed whether psychiatrists disclosed information about antipsychotic medications and the risks of tardive dyskinesia. It also assessed psychiatrists' documentation practices, although these practices are not reported here. We used a shortened version of a self-report questionnaire that had been previously studied (6).

Two scales were derived from the questionnaire: the behavior scale and the antipsychotic attitude scale. The behavior scale summarized whether psychiatrists provided information about antipsychotic medications and tardive dyskinesia to competent patients or to substitute decision makers of incompetent patients. The antipsychotic attitude scale showed psychiatrists' attitudes toward informed consent for antipsychotic medications and tardive dyskinesia. Both scales were scored on a Likert scale of 1 to 5. The behavior scale is the mean of individual items on the scale; items are scored as 1, always; 2, almost always; 3, sometimes; 4, almost never; and 5, never.

Face and content validity of the earlier version of the self-report questionnaire was evaluated by 19 experienced clinicians. After revisions, 60 psychiatrists and general practitioners tested the validity of the questionnaire by participating in a structured interview and completing the questionnaire and the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (8). The physicians' behavior scale scores were correlated with the disclosure practices that they reported in the structured interview (r=.62, N=60, p<.001, two-tailed test) (6). Physicians did not appear to answer in a socially desirable manner; neither the behavior scale scores nor the antipsychotic attitude scale scores were significantly associated with Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale scores (6,8). Physicians who participated in the validity and reliability studies provided informed consent.

The two-and-a-half week test-retest reliability measures for the behavior scale and the antipsychotic attitude scale were .82 and .85, respectively (intraclass correlation coefficient). Internal consistency measures for the behavior scale and the antipsychotic attitude scale were .94 and .85, respectively (Cronbach's alpha).

The sample size was chosen so that a .67 standard deviation could be detected between strata with an alpha of .01 and 80 percent power. The t test and correlation analysis were used. Percentages were calculated on the basis of the number of respondents to questionnaire items. Where the variables' distribution was skewed, the data were trimmed in the bivariate analyses.

Results

The response rate was 72 percent (N=427). Respondents tended to be younger than nonrespondents (t=2.55, df=602, p<.05). The mean±SD age of the psychiatrists surveyed was 43.6±10.6 years. A total of 55 percent of the psychiatrists surveyed (N=235) were male, and 84 percent (N=360) prescribed antipsychotic medications, each to a mean of 72.2±140 patients per year and a median of 30 patients per year. Psychiatrists surveyed spent a mean of 70.6±109 hours per year and a median of 49 hours per year in continuing education and a mean of 11.6±23 hours per month reading medical journals.

Most psychiatrists surveyed routinely disclosed to their patients the reasons for prescribing antipsychotic medications and the possible side effects of the medications, including acute extrapyramidal symptoms. Seventy-eight percent of the psychiatrists surveyed (N=243) routinely disclosed the possible side effect of tardive dyskinesia, with 50 percent (N=157) always disclosing the risk of tardive dyskinesia and 28 percent (N=86) almost always disclosing the risk. Only 3 percent of the respondents (N=9) rarely or never disclosed that tardive dyskinesia is a potential side effect of taking a conventional antipsychotic medication. The mean item score on the behavior scale was 2.21± .61 (N=359).

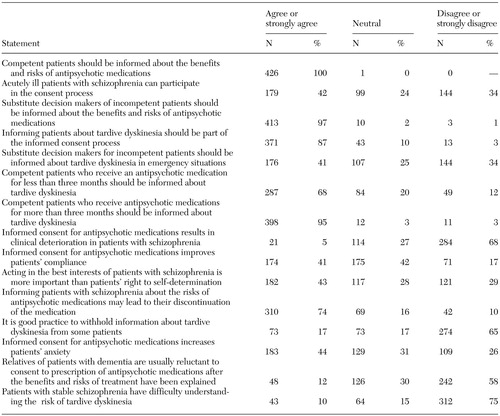

Table 1 shows that almost all respondents believed that competent patients or substitute decision makers of incompetent patients should be informed about the benefits and risks of antipsychotic medications. Psychiatrists surveyed were divided about disclosing information about tardive dyskinesia to patients or to relatives when the patient received an antipsychotic medication for less than three months or in an emergency situation. Respondents were also divided about whether acutely ill patients could participate in the consent process. Concerns were raised by respondents about the impact of disclosure on patient outcome and whether informed consent improves compliance, causes patients to discontinue taking their medication, or increases patients' anxiety.

Women (mean score of 2.05±.6, N=151) disclosed information about antipsychotic medications more frequently than men (mean score of 2.05±.6, N=151, compared with 2.31 ±.6, N=205; t =−3.45, df=354, p=.001). Disclosure was negatively correlated with the number of patients treated by the respondent (r=.12, p<.05, two-tailed test) and with the respondents' estimate of the prevalence of tardive dyskinesia (r=.13, p<.05, two-tailed test). Attitudes toward informed consent were correlated with disclosure practices (r=-.316, N=359, p<.01, two-tailed test). Age (dichotomized at 40 years) hours spent reading medical journals per month, and hours per year spent in continuing education were not correlated with disclosure.

Age (dichotomized at 40) gender, hours spent reading medical journals per month, and hours per year spent in continuing education did not correlate with whether the respondent disclosed information about tardive dyskinesia. Attitudes toward informed consent correlated with disclosing information about tardive dyskinesia (r=.35, p<.01, two-tailed test).

Of the 360 respondents who prescribed antipsychotic medication, 17 percent of the psychiatrists (N=60) reported that they were more likely to disclose information about antipsychotic medications and their side effects to competent patients after codification of informed consent in legislation in Ontario, and 19 percent (N=65) were more likely to disclose more information to relatives or to the substitute decision makers of incompetent patients after the legislation.

Discussion and conclusions

Psychiatrists who had more positive attitudes about informed consent were more likely to disclose information about antipsychotic medications and the side effects of tardive dyskinesia. Although one study found that disclosing information about antipsychotic medication did not have an adverse effect on patients' medication compliance and readmission rate (9), our study revealed that respondents were concerned that disclosure of the benefits and risks of antipsychotic medication would affect patient care.

Age of the respondents did not predict whether they would disclose information about antipsychotic medications and the risk of tardive dyskinesia. Although women were found to be more likely to disclose information about antipsychotic medications, which supported the results of other studies (5), the gender difference was not significant. In addition, women were not more likely to disclose the risk of tardive dyskinesia. We also found that continuing education was not related to disclosure, substantiating the findings of other studies (10). However, continuing education likely included topics that were not relevant to this study. The association between the number of patients seen by the psychiatrist and the tendency to disclose the risks and benefits of antipsychotic medications has also been noted (5). However, we found that this association did not remain after multivariate analyses were performed. Benson (5) found that the time spent reading medical journals was associated with disclosure, whereas our study did not.

Our results can probably be generalized to other jurisdictions in both Canada and the United States, because the common law standard in Canada and the standard codified in legislation in Ontario are similar to that enunciated in the United States (1,3). Our study may show that the psychiatrists that we surveyed had an increased tendency to disclose information about the risks and benefits of antipsychotic medications, because informed consent legislation came into effect shortly before this survey was conducted. It would also be interesting to determine whether the association between attitudes and disclosure would hold in other clinical situations and jurisdictions.

Our study was conducted before atypical antipsychotic medications were commonly prescribed. At the time of our study, it was known that clozapine had a minimal risk of causing tardive dyskinesia and risperidone's profile was unclear because the medication was still new. Hence the questionnaire did not distinguish between conventional and atypical antipsychotics. The extent to which our results about psychiatrists' attitudes toward informed consent and their disclosure practices apply to atypical antipsychotic medications, which have a different profile of side effects, needs to be examined. Patients should be informed about the benefits and risks of conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications so that they can be empowered to make treatment decisions when they are competent to do so.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants 6606-5304-301 and 6606-4226-57P from the Canadian National Health Research and Development Program. The authors acknowledge the collaboration of Jack Williams, Ph.D., on the statistical aspects of this project.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Toronto. Dr. Schachter is also with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 250 College Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5T 1R8 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Kleinman is also with the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto.

|

Table 1. Psychiatrists' self-reported attitudes about obtaining informed consent for antipsychotic medications and tardive dyskinesia (N=427)

1. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS: Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

2. Dickens BM: Informed consent, in Canadian Health Law and Policy. Edited by Downie J, Caulfield T. Markham, Ontario, Butterworths, 1999Google Scholar

3. Consent to Treatment Act. Statutes of Ontario, 1992Google Scholar

4. Tardive dyskinesia: summary of a Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137:1163–1172, 1980Link, Google Scholar

5. Benson PR: Informed consent: drug information disclosed to patients prescribed antipsychotic medication. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 172:642–653, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Schachter D, Kleinman I: Survey of Physicians' Practice: Informed Consent and Tardive Dyskinesia. Pilot Project. Grant No. 6606–4226–57P. Canada, National Health Research and Development Program, 1993Google Scholar

7. Schachter D, Kleinman I: Psychiatrists' documentation of informed consent. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 43:1012–1017, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Crowne DP, Marlowe D: A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology 24:349–354, 1960Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Kleinman I, Schachter D, Koritar E: Informed consent and tardive dyskinesia. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:902–904, 1989Link, Google Scholar

10. McAuley RG, Paul WM, Morrison GH, et al: Five-year results of the peer assessment program of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Canadian Medical Association Journal 143:1193–1199, 1990Google Scholar