The Availability of Psychiatric Programs in Private Substance Abuse Treatment Centers, 1995 to 2001

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The high rate of co-occurrence of substance abuse and mental disorders renders the availability of psychiatric programs, or integrated service delivery, a vital quality-of-care issue for substance abuse clients. This article describes the availability of psychiatric programs and integrated care for clients with severe mental illness in the private substance abuse treatment sector and examines these patterns of service delivery by profit status and hospital status. METHODS: Survey data from the National Treatment Center Study, which is based on a nationally representative sample of privately funded substance abuse treatment centers, were used to identify the proportion of centers that offered psychiatric programs in 1995-1996, 1997-1998, and 2000-2001. Centers reported whether they treated clients with severe mental illness on-site or referred them to external providers. Repeated-measures general linear models were used to test for significant changes over time and to assess mean differences in service availability by profit status and hospital status. RESULTS: About 59 percent of private centers offered a psychiatric program, and this proportion did not significantly change over time. The proportion of centers that referred clients with severe mental illness to external providers increased significantly from 57 percent to 67 percent. For-profit centers and hospital-based centers were significantly more likely to offer psychiatric programs and were less likely to refer severe cases to other providers. CONCLUSIONS: Although the importance of integrated care for clients with dual diagnoses is widely accepted, data from the private substance abuse treatment sector suggest that this pattern of service delivery is becoming less available.

Proper diagnosis of mental health disorders among clients who have sought treatment for substance abuse has become an issue of major clinical concern (1,2). A large proportion of substance abuse clients have a co-occurring psychiatric disorder (3,4). For those who enter substance abuse treatment and cannot obtain appropriate psychiatric care, overcoming the barriers to treatment may have been futile. Left untreated, substance abuse treatment clients with co-occurring psychiatric disorders are likely to have worse treatment outcomes (5,6).

Experts in mental health and substance abuse treatment often call for integrated psychiatric and substance abuse treatment services for this population (7). This model of integrated care assumes that the delivery of these two types of services occurs within a single organizational setting (8). Historically, mental health and substance abuse treatment services have been delivered by separate organizations and separate health care systems (2,8,9). Reflecting this split and adding complexity to it are the range of separate and combined mechanisms for providing payment for care (10,11,12). Although there is near consensus about the importance of integrated service delivery, it is less clear whether substance abuse treatment centers are able to offer such services (13). A recent study of public-sector programs found that less than half of California counties provide integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment services (14). The extent to which these services are integrated within private-sector substance abuse treatment organizations is unknown.

Clients who initiate substance abuse treatment enter services with varying levels of psychological well-being (7). A substantial proportion of clients may have co-occurring mood or anxiety disorders, whereas others arrive with severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia. These clients with co-occurring substance abuse and severe mental illness are often referred to as clients with dual diagnoses (8). Given the severity of these clients' psychiatric needs, substance abuse treatment centers may refer them to other service providers. When substance abuse treatment centers refer the clients to other agencies for care, the centers are no longer providing integrated care for this population. Although these referrals represent an improvement over receipt of no mental health care, they are not consistent with an integrated service delivery model under which substance abuse treatment and psychiatric care are provided in a single setting (2,8,14).

Substance abuse treatment programs can have various organizational forms (15), which may influence the availability of psychiatric services. For example, centers located in hospitals have access to greater specialized medical resources, which should increase the likelihood of their offering psychiatric programs as well as reduce the rate of referral of clients to other providers.

The center's profit status may also be a relevant organizational factor. Although a study of outpatient drug abuse programs reported that for-profit programs provided less mental health care than publicly owned programs (16), there are several possible reasons for greater availability of psychiatric services in for-profit settings relative to private nonprofit centers. First, for-profit centers may offer a more comprehensive array of services under one roof, particularly if the center is in a hospital, thereby increasing the variety of clients they can serve (17). Second, for-profit centers generally obtain a greater proportion of their revenues from private insurance claims (18,19), and reimbursement rates may be more generous (20) or more easily obtained for psychiatric services than for substance abuse treatment services (10).

The study reported here considered three research questions pertaining to the delivery of psychiatric services by using survey data collected from a nationally representative sample of privately funded substance abuse treatment centers. First, did the prevalence of psychiatric programs change between 1995-1996 and 2000-2001? Second, was there an increase in the proportion of centers that provided integrated care for clients with severe mental illness? Finally, do the patterns of psychiatric programs and integrated care vary according to a center's profit status and its location in a hospital setting?

Methods

Sample

The National Treatment Center Study began in 1995 to measure changes in the delivery of substance abuse treatment services in the private sector. A two-stage stratified sampling process was used to identify a nationally representative sample of privately funded treatment centers (21,22). To be eligible for the study, centers were required to receive less than 50 percent of their funding from government block grants or contracts. In addition, programs were required to offer a level of care that was at least equivalent to structured outpatient services (23). A total of 450 eligible facilities (89 percent) participated in the study.

Trained fieldworkers collected data during three face-to-face structured interviews in 1995-1996, 1997-1998, and 2000-2001 (24 months and 60 months after the baseline interview). These interviews were conducted with the center's program administrator and the clinical director if such a position existed. The human subjects committee within the institutional review board at the University of Georgia approved this research design.

Over the course of the study, there has been some attrition within the panel of 450 privately funded substance abuse treatment facilities, primarily due to closure of centers. Forty-three of the original 450 centers had been closed by the 24-month follow-up interview. An additional 63 centers had closed before the 60-month follow-up interview. However, among centers that remained open, study participation rates of 92 percent (24 months) and 88 percent (60 months) were achieved. The data presented in this article are derived from the 303 centers that participated in the three interviews.

Measures

Two measures of the availability of psychiatric services were considered. Administrators were asked whether their center offered a psychiatric program (1=yes, 0=no). In addition, administrators indicated whether clients with severe mental illness were treated at the center or were referred to other health service providers (1=referred elsewhere, 0=treated at center). The practice of referring clients with severe mental illness to external agencies represents a failure by the substance abuse treatment facility to provide integrated care for this population.

Two organizational variables were included in the analysis. First, a dichotomous measure indicated hospital status (1=hospital setting, 0=freestanding). Second, administrators reported the profit status of the center (1=for-profit, 0=nonprofit).

Data analysis

Given the longitudinal design of the study, repeated-measures general linear models were used to test for significant overall changes over time, mean differences based on hospital status and profit status, and interaction effects between these organizational characteristics and time. In addition to descriptive statistics, F statistics, levels of significance, and mean square error (MSe) terms are reported. Listwise deletion yielded 287 centers for the psychiatric program analysis and 282 centers for analyzing integrated care availability for clients with severe mental illness.

Results

The provision of treatment programming for psychiatric disorders at private substance abuse treatment centers was essentially stable during the study period. In 1995-1996, 170 treatment centers (59 percent) offered a psychiatric program. A total of 178 centers (62 percent) in 1997-1998 and 181 centers (63 percent) in 2000-2001 offered a psychiatric program. The modest increase observed over time was not statistically significant.

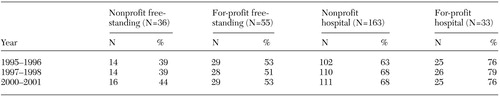

Descriptive statistics on the availability of psychiatric programs are presented in Table 1. Although no overall significant trend over time was observed, significant mean differences based on profit status and hospital status were noted. For-profit substance abuse treatment centers were significantly more likely than nonprofit centers to offer programs for psychiatric disorders (F=4.443, df=1, 283, p<.05, MSe=.400). In addition, private substance abuse treatment centers that were located in hospital settings were significantly more likely to offer treatment programs for psychiatric disorders than their freestanding counterparts between 1995 and 2001 (F=22.714, df=1, 283, p<.001, MSe=.400).

An increase over time was observed in the proportion of private substance abuse treatment centers that referred clients with severe mental illness to other service providers rather than delivering integrated services at their center. In 1995-1996, a total of 161 substance abuse treatment centers (57 percent) did not treat clients with severe mental illness on-site, instead referring those clients to external service providers. A total of 177 centers (63 percent) used this external referral approach in 1997-1998, and 189 centers (67 percent) reported this practice in 2000-2001. This overall pattern of variation over time was statistically significant (F=8.09, df=2, 556, p<.001, MSe=.133). Further examination revealed a significant linear association (F=13.738, df=1, 278, p<.001, MSe=.143), but the quadratic trend was nonsignificant, which suggests that the change is better described as a line rather than as a curve.

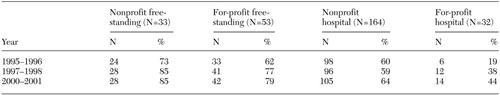

The pattern of increase over time was not contingent on type of center—the rate of increase was similar across various types of substance abuse treatment centers. However, significant mean differences were noted in the referral of clients with severe mental illness to other facilities on the basis of profit status and hospital status. For-profit centers were significantly less likely to refer clients with dual diagnoses to external service providers (F=11.047, df=1, 278, p<.01, MSe=.391), as were centers located in hospitals as opposed to freestanding substance abuse treatment centers (F=31.568, df=1, 278, p<.001, MSe=.391). The proportion of the various types of centers that referred clients with dual diagnoses to external providers is shown in Table 2.

Discussion

Analyses of this nationally representative sample of privately funded substance abuse treatment centers demonstrated that a majority of the facilities offered programs for psychiatric disorders between 1995 and 2001. The proportion of centers that offered this type of program was stable over the period. For-profit centers and centers based in hospitals were consistently more likely to offer psychiatric programs within their centers.

Although there has been extensive discussion in the literature of the importance of integrating substance abuse treatment and psychiatric services for clients with dual diagnoses, this integration has not become a reality in privately funded substance abuse treatment centers. In fact, our data suggest the opposite—namely, that an increasing number of treatment centers are referring clients with severe mental illness to service providers outside the substance abuse treatment facilities. The data are consistent with the results of recent analyses of service use patterns among individuals that demonstrated that the proportion of clients with dual diagnoses who receive integrated substance abuse and mental health care is low (1,2).

In addition, the likelihood that a substance abuse client who also has psychiatric treatment needs will have access to psychiatric services varies by type of facility. Clients who enter freestanding nonprofit substance abuse treatment programs are particularly at risk of not having access to a program for psychiatric disorders; clients with dual diagnoses are very likely to be sent to other treatment facilities. Although these external referral patterns may mean that clients with dual diagnoses are linked to services that they might not otherwise receive, the data nevertheless indicate that private substance abuse treatment centers are becoming less likely to provide the integrated treatment that has been identified as most effective (8). Furthermore, although referrals to other providers may ensure that the client's mental health needs are met, the external providers may not be able to fully meet clients' substance abuse treatment needs.

Certain limitations of our research must be noted. First, the study included only privately funded substance abuse treatment centers. Thus the patterns we observed may not be generalizable to the public sector. In addition, the study should be interpreted only in terms of internal organizational change, not change within the entire system of substance abuse treatment, given that we examined only centers that were open between 1995 and 2001. It is not known whether these findings are generalizable to recently opened private substance abuse facilities.

Conclusions

Although there has been little change in the availability of psychiatric programs in the private substance abuse treatment system since 1995, variations in program availability according to characteristics of the center raise important concerns about the quality of care received by substance abuse clients who have co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, there appears to be a trend away from the integrated delivery of substance abuse and mental health services for clients with severe mental illness. It should be noted that such a fragmentation of service delivery has been identified as disadvantageous from a long-term cost-effectiveness perspective (24). The significance of this issue for the welfare of clients with dual diagnoses warrants continued monitoring of trends within the private sector as well as comparisons with the public substance abuse treatment system.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the research support of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA-13110) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01-AA-10130).

The authors are affiliated with the Center for Research on Behavioral Health and Human Services at the University of Georgia, 101 Barrow Hall, Athens, Georgia 30602-2401 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Proportion of substance abuse treatment centers offering programs for clients with psychiatric disorders, by year and type of center (N=287)

|

Table 2. Proportion of substance abuse treatment centers referring clients with severe mental illness to external providers, by year and type of center (N=282)

1. Green-Hennessey S: Factors associated with receipt of behavioral health services among persons with substance dependence. Psychiatric Services 53:1592–1598, 2002Link, Google Scholar

2. Watkins KE, Burnam A, Kung F-Y, et al: A national survey of care for persons with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 52:1062–1068, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, et al: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Study. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:313–321, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Skinstad AH, Swain A: Comorbidity in a clinical sample of substance abusers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 27:45–64, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Agosti V, Nunes E, Levin F: Rates of psychiatric comorbidity among US residents with lifetime cannabis dependence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 28:643–652, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Primm AB, Gomez MB, Tzolova-Iontchev I, et al: Mental health versus substance abuse treatment programs for dually diagnosed patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 19:285–290, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Drake RE, Wallach MA: Dual diagnosis:15 years of progress. Psychiatric Services 51:1126–1129, 2000Google Scholar

8. Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, et al: Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:469–476, 2001Link, Google Scholar

9. Young NK, Grella CE: Mental health and substance abuse treatment services for dually diagnosed clients: results of a statewide survey of county administrators. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:83–92, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Merrick EL, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, et al: Benefits in behavioral health carve-out plans of Fortune 500 firms. Psychiatric Services 52:943–948, 2001Link, Google Scholar

11. Hodgkin D, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, et al: Why carve out? Determinants of behavioral health contracting choice among large US employers. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 27:178–193, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Salkever DS, Shinogle J, Goldman H: Mental health benefit limits and cost sharing under managed care: a national survey of employers. Psychiatric Services 50:1631–1633, 1999Link, Google Scholar

13. Brems C, Johnson ME, Namyniuk LL: Clients with substance abuse and mental health concerns: a guide for conducting intake interviews. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 29:327–334, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Steele LD, Rechberger E: Meeting the treatment needs of multiply diagnosed consumers. Journal of Drug Issues 32:811–824, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Hser Y-I, Joshi V, Maglione M, et al: Effects of program and patient characteristics on retention of drug treatment patients. Evaluation and Program Planning 24:331–341, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Friedmann PD, Alexander JA, D'Aunno TA: Organizational correlates of access to primary care and mental health services in drug abuse treatment units. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 16:71–80, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Roman PM, Johnson JA, Blum TC: The transformation of private alcohol problem treatment: results from a national study. Advances in Medical Sociology 7:321–342, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Rodgers JH, Barnett PG: Two separate tracks? A national multivariate analysis of differences between public and private substance abuse treatment programs. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 26:429–442, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wheeler JRC, Nahra TA: Private and public ownership in outpatient substance abuse treatment: do we have a two-tiered system? Administration and Policy in Mental Health 27:197–209, 2000Google Scholar

20. Dickey B, Azeni H: Persons with dual diagnoses of substance abuse and major mental illness: their excess costs of psychiatric care. American Journal of Public Health 86:973–977, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Johnson JA, Roman PM: Predicting closure of private substance abuse treatment facilities. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 29:115–125, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Milne SH, Blum TC, Roman PM: Quality of management in a health care setting: a study of substance abuse treatment centers. Advances in the Management of Organizational Quality 5:215–248, 2000Google Scholar

23. Mee-Lee DL, Gartner L, Miller MM, et al: Patient Placement Criteria for the Treatment of Substance-Related Disorders, 2nd ed. Chevy Chase, Md, American Society of Addiction Medicine, 1996Google Scholar

24. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: The cost of treating substance abuse patients with and without comorbid psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services 50:1309–1315, 1999Link, Google Scholar