Enhancement of Treatment Adherence Among Patients With Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Because about one-third of persons with bipolar illness take less than 30 percent of their medication and because nonadherence is associated with rehospitalization and suicide, the literature was searched to identify controlled studies of enhancement of treatment adherence among persons with bipolar disorder. METHODS: Studies published up to October 2003 were evaluated. Those selected for review were controlled trials that used samples of adults with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and that measured adherence to either mood-stabilizing medication or psychotherapy. Information was extracted on the diagnostic composition and size of the study group, the type and duration of the intervention, the method of measuring adherence, and outcomes. RESULTS: Eleven studies met inclusion criteria. Although the literature on enhancing treatment adherence among persons with bipolar disorder is limited, the existing data are promising and demonstrate development over time in our understanding of how best to manage this illness. Interventions that have been shown to be effective include interpersonal group therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, group sessions for partners of persons with bipolar disorder, and patient and family psychoeducation. Effective therapies occur in the context of long-term management of illness that incorporates a good understanding of medications and their risks and benefits as well as education about illness awareness and self-management. The majority of effective therapies feature an interactional component between patients and their care providers or therapists. CONCLUSIONS: Adherence to treatment for bipolar disorder may be enhanced by interventions that address issues of appropriately taking medications to manage illness. For optimum outcomes, promotion of adherence must be integrated into the medication management of bipolar illness.

Bipolar disorder is a severe and recurrent condition that affects nearly 2 percent of the adult population in the United States (1). It has been reported that the overall economic burden of bipolar disorder in the United States is $45 billion annually, with $7 billion in direct treatment costs (2,3), and that the costs of medication and treatment encounters for an individual with bipolar illness exceed $17,000 annually (4). Nonadherence to treatment has been identified as a frequent cause of recurrence or relapse of bipolar disorder (5,6) that is associated with such negative consequences as rehospitalization (7) and suicide (8). Scott and Pope (9) recently reported that one in three persons with bipolar disorder fail to take at least 30 percent of their medication. Additionally, nonadherence may be a growing problem among patients with bipolar disorder, because the prevalence of atypical forms of the disorder is increasing and more people with bipolar illness have comorbid substance use disorders (5,10).

Although drug treatments for bipolar disorder have proliferated rapidly in the past decade (11), a substantial gap exists between the efficacy of known treatments and treatment effectiveness in real-world settings. Guscott and Taylor (12) have noted that the major reason for the discrepancy between efficacy and effectiveness in lithium treatment of bipolar disorder is poor treatment adherence. Interventions that enhance adherence to prescribed medication regimens for bipolar disorder are critically needed (5). Enhancing adherence is a complex clinical challenge for a number of reasons, including the large number of factors that contribute to treatment nonadherence (13), current lack of clarity in defining and monitoring adherence (5), and a paucity of research data on how to best enhance treatment adherence (5,12,13,14).

Numerous factors appear to influence treatment adherence, including patient factors, such as younger age, single status, male gender, and low educational level (5,15,16); the symptoms of illness, such as hypomanic denial (17) and psychosis (18); and comorbid disorders, such as personality disorders (19,20) and substance use disorders (21). Side effects of medications and unfavorable personal attitudes toward treatment may also have a negative impact on treatment adherence (22,23). The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions to enhance adherence will hinge on the ability to address the factors that are changeable and most relevant to treatment adherence in a given individual. These factors will undoubtedly differ depending on the individual's psychiatric symptoms, medication response patterns, age, gender, and cultural context.

Although psychotherapy for bipolar disorder is known to generally improve the outcome of illness (24,25), it has been reported that interventions that focus on treatment adherence may yield positive results in this specific area (26,27). This review article summarizes published controlled studies and reports of interventions that have been evaluated with respect to enhancing treatment adherence among persons with bipolar disorder. Patterns seen across the selected studies are discussed, as are the challenges of assessing treatment adherence. Areas for future research are recommended.

Methods

The objective of the review was to identify controlled published studies that evaluated enhancement of adherence in bipolar disorder. A MEDLINE search for studies published in the English language up to October 2003 was undertaken. Key search words included bipolar disorder, manic-depressive disorder, compliance, adherence, and outcome. Proceedings from recent professional meetings were also examined for abstracts evaluating treatment adherence for bipolar disorder. Citations from the articles selected for inclusion were also evaluated for additional studies. To be included in the review, studies had to have samples of adult participants with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, to use a controlled-trial method, and to assess adherence to either mood-stabilizing medication or psychotherapy. We reviewed articles that met these criteria and extracted information on type and duration of the intervention, diagnostic composition and size of the study group, the method of measuring adherence, and adherence-related outcomes.

Methods of Measuring Adherence in Studies of Enhancement of Adherence to Treatment for Bipolar Disorder

•Self-report: Adherence is evaluated via a Likert scale or by using a standardized tool such as the Medication Compliance Questionnaire (reference 30)

•Informant report: Patients are asked to designate an individual who can evaluate their treatment adherence

•Physician report: The treating physician estimates the patient's treatment adherence

•Frequency of visits: The patient's missed appointments are documented in the scheduling record

•Serum lithium levels: Tests are performed serially or on a single occasion

•Red blood cell lithium level: This test may be done along with serum levels

•Chart review: Notations of adherence difficulties are obtained from medical charts

•Composite adherence assessment: The clinician uses multiple sources to determine a composite score (reference 26)

| • | Compliance index: An independent judge evaluates all available information and assigns a compliance index rating on a 3-point ordinal scale: compliance, minor noncompliance, and major noncompliance | ||||

| • | Compliance: the patient is adhering to the regimen; minor noncompliance: the patient fails to obtain blood level tests, misses appointments without notifying the clinic, or forgets the prescribed dosages; major noncompliance: the patient deviates significantly from the treatment regimen by terminating medication against medical advice, dropping out of treatment, or taking medication too chaotically to maintain adequate blood levels | ||||

•Mixed methods: Adherence is measured by combinations of selected specific measures (for example, self-report plus serum levels)

Results

Measurement of treatment adherence

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria, and most—seven studies, or 64 percent—were published in the past five years. Methods of measuring adherence-related outcomes varied from self-report to plasma measurement to independent assessment of adherence patterns. The variety of methods reflects the challenges involved in accurately measuring treatment adherence of persons with bipolar illness. Seven studies used serum drug levels, either alone or with other measures, to determine medication adherence. As expected, the earlier reports focused solely on lithium adherence. Reflective of the rapid expansion of the pharmacopoeia of bipolar disorder over the past decade, the most recent study, a report by Colom and colleagues (28) published in 2003, also included an assessment of anticonvulsant medications. None of the studies evaluated use of atypical antipsychotic compounds in the context of adherence assessment.

Three of the 11 studies relied solely on patient self-reports (29,30,31). Although self-reports are easily attainable, it has been suggested that patients' reports may overestimate adherence (32). However, Lam and colleagues (33) recently noted significant agreement between patients' reports of adherence and serum levels. In that study, 91 percent of 44 patients who reported good adherence—which was defined as missing their medication fewer than three times a month—also had adequate serum levels of mood stabilizers. Cochran (26) reported six different measures of "medical compliance": self-report, informant report, physician report, serum lithium levels, chart review, and an independently judged "compliance index." Miklowitz and colleagues (34) used an independent assessment done by a research assistant who collected and used information from patients' self-reports and physicians' observations.

The box on this page summarizes the methods used to evaluate treatment adherence in the studies included in this analysis. Although the studies did not specifically use medication refill records or microelectronic devices, they have also been identified as reasonable additional methods to evaluate treatment adherence (5,14). Although no standard has been established for measuring treatment adherence for bipolar disorder, it has been suggested that a mixed method that combines selected measures is most likely to provide the most accurate assessment of treatment adherence among patients with bipolar disorder (5,28,33).

General findings

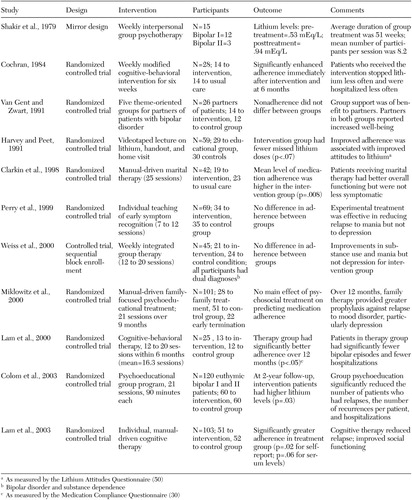

The 11 studies that met inclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1. Nine involved randomized clinical studies. The earliest randomized study, by Shakir and colleagues (35), used a mirror image design, which retrospectively evaluated lithium levels for two years before the intervention and compared them with lithium levels after the start of the intervention. The study by Weiss and colleagues (31) recruited patients in sequential blocks to receive either the experimental intervention or treatment as usual. Seven of these 11 studies focused narrowly on medication adherence. Others, such as the study by Cochran (26), viewed treatment adherence more broadly; it included maintenance of a lithium regimen, scheduled blood tests, and attendance at medical appointments.

In eight of the studies, samples were relatively small, ranging from 15 to 69 patients. Larger trials were the study by Miklowitz and colleagues (34), which had a sample of 101 patients, and the most recent studies by Colom and colleagues (28), which had 120 participants, and by Lam and colleagues (33), which had 103 participants. Although participants met strict selection criteria for these studies, generalizations are difficult because of the wide disparity in selected populations. For example, Clarkin and colleagues (29) conducted a marital intervention study and selected middle-aged patients with bipolar illness who had been married for an average of 17 years. Perry and colleagues (36) selected patients who had experienced relapse in the 12 months before study entry, and Lam and associates (30) designed their cognitive therapy intervention study for a "very difficult, vulnerable group of patients" who were taking mood stabilizers but who "were still relapsing." In contrast, Harvey and Peet (37) selected lithium clinic attendees for their study who were apparently more stable than patients in the other studies. The study by Colom and colleagues (28) required participants to be outpatients who were in remission for at least six months before inclusion in the study. Similarly, the recent study by Lam and colleagues (33) recruited only individuals who were not experiencing a mood episode at study entry. The study by Weiss and colleagues (31) recruited only individuals with bipolar disorder and comorbid substance use.

Of the 11 studies identified, seven (64 percent) suggested that the chosen psychosocial intervention improved treatment adherence among patients with bipolar disorder. In contrast, van Gent and Zwart (38) did not find significant improvement in medication adherence, measured by serum lithium levels, when outpatients were assigned to group therapy sessions for partners only instead of standard treatment. Perry and colleagues (36) found no difference in treatment adherence between experimental and control groups after an intervention that emphasized early recognition of bipolar symptoms. Weiss and colleagues (31) found that persons with dual diagnoses who received integrated group therapy had significant improvements in substance use compared with controls; however, no difference in medication adherence was noted. Miklowitz and colleagues (34) reported the results of a randomized trial of a nine-month program of family therapy. Although their treatment intervention was associated with lower relapse rates and less symptom severity, it had no main effect on medication adherence. However, it must be noted that in the study by Miklowitz and colleagues (34), the "average" study patient was reasonably adherent to the medication regimen. The study by Colom and colleagues (28) found that lithium adherence was improved with psychoeducation, but adherence to valproate and carbamazepine was not significantly different than that of a control group.

Interventions for enhancement of treatment adherence

To enhance treatment adherence among persons with bipolar disorder, the controlled trials reviewed here generally used treatments that were psychoeducational and patient focused. Nearly half the interventions involved a group-, couple-, or family-focused format. Both the intervention and the assessment of adherence may be maximized when family members or patients' significant others are involved, although sole dependence on partners or significant others appears to produce limited results (38). As might be expected given the chronicity of bipolar disorder, most interventions in the controlled trials were moderate to long term, with a mean of 13 sessions. The intervention for persons who had bipolar disorder and a comorbid substance use disorder that was developed by Weiss and colleagues (31) consisted of 12 sessions in the initial version and was expanded to 20 sessions in the final version.

The longitudinal and interactive aspect of the intervention appears critical for effectiveness (39). As has been noted by Mullen and colleagues (40), written information alone is of little benefit. Scott (41) suggested that difficulties with adherence to medication may be tackled by exploring barriers to adherence and by using cognitive and behavioral techniques to enhance adherence—for example, by challenging automatic thoughts about medications. The more recent studies use standardized or manual-driven psychoeducational interventions, with specific formats and goals that can be replicated in other treatment settings.

Overall, psychoeducational interventions that focus specifically on bipolar illness appear effective in improving outcomes and treatment adherence, although improved adherence does not necessarily correlate with improved symptoms. Recent studies by Lam and colleagues (33) and Colom and colleagues (28) have minimized the effects of acute symptom state on the evaluation of psychosocial interventions in measuring bipolar outcomes by enrolling only persons whose illness is in remission or persons who were not experiencing an acute mood episode at study entry. Recent studies have substantially advanced our understanding of optimizing treatment outcomes for bipolar disorder with psychosocial interventions. However, the interaction between outcomes and treatment adherence appears to be more than a simple cause-and-effect relationship.

Discussion

Although the literature on enhancement of treatment adherence among persons with bipolar disorder remains limited, the existing data are promising and demonstrate development over time in our understanding of how best to manage this often devastating illness. Effective therapies that maximize adherence are patient focused and include family members or significant others whenever possible. Effective therapies occur in the context of long-term management of illness that incorporates a good understanding of medications and their risks and benefits as well as education about illness awareness and illness self-management. The majority of effective therapies feature an interactional component between patients and care providers or therapists.

Although the developing literature on the enhancement of adherence to treatment for bipolar disorder appears encouraging, a number of challenges remain. Treatment nonadherence continues to be a major factor in relapse and poor outcomes for patients with bipolar disorder. Assessment of treatment adherence remains nonstandardized, making comparisons across studies problematic. The most recent studies feature multidimensional assessments that include patients' self-reports, biological measures, and information from family members or significant others. Use of standardized rating scales (9,33,39) may be of benefit in evaluating self-assessment of adherence to mood stabilizers. The widespread use of atypical antipsychotic compounds in the management of bipolar illness presents a new challenge, because, unlike with lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine, serum levels of antipsychotic medications are typically not monitored in clinical settings. Some studies have used indirect patient features to evaluate adherence, such as attitudes toward medication (37), but potentially important relationships, such as how treatment attitudes and locus of control affect treatment adherence, remain unclear.

The psychotherapeutic mechanisms of action for improvements in the outcome of bipolar disorder and in adherence are not known. As noted by Colom and colleagues (28), "It remains unclear whether prevention of depressive episodes comes from a real psychoeducative action on habits and adherence or from a cognitive effect of psychoeducation itself." It has been speculated that promotion of treatment adherence may explain, at least in part, the positive outcomes of psychoeducational approaches (28).

Interventions to improve medication adherence among individuals with schizophrenia have been better studied than similar interventions among individuals with bipolar disorder (42), and they may offer some useful guidelines. Like bipolar disorder, schizophrenia is a chronic, relapsing serious mental disorder that profoundly affects multiple domains in the lives of affected individuals. A recent review of the literature that examined treatment adherence for schizophrenia suggested that psychoeducation alone for patients and their families is largely ineffective without accompanying behavioral components and supportive services (42). Common behavioral strategies include providing patients with concrete tools, such as reminders, self-monitoring tools, and assistance in negotiating treatment issues with mental health providers (43). Additionally, studies of patients with schizophrenia suggest that interventions developed to address medication nonadherence may be more likely to succeed than programs covering a wider range of problem areas (42).

Research on treatment adherence in schizophrenia suggests that a health beliefs model approach, which is generally logic based, may be of limited utility (42). For individuals with bipolar disorder, it is not clear how useful a health beliefs model may be in understanding and modifying treatment adherence. At least in some cases, exploration of an individual's beliefs about bipolar illness and therapy may lead to changes in treatment planning and improve adherence to mood stabilizers (44). Our preliminary work, which involved individuals with bipolar disorder who received treatment in a community mental health clinic (45), suggests that clear identification of features of the illness that are amenable to treatment with medication, focused attention on goal identification and problem solving, and the group interaction process all contribute substantially to changing attitudes toward medication.

Supporting the notion that adherence-related attitudes and behaviors may be improved with specific interventions, Scott and Tacchi (46) recently suggested that concordance therapy improved attitudes toward lithium, self-reported lithium adherence, and serum lithium levels among individuals with bipolar disorder who were nonadherent to lithium prophylaxis. Future studies evaluating adherence should address patient-centered measures, such as attitudes toward medication and insight into illness, so that features of adherence behavior that are amenable to change can be identified and targeted for intervention.

Manual-driven therapies are increasingly emphasized in mental health care (47,48,49,50) and have the advantage of being replicable in a variety of treatment settings. Interventions involving a group format appear effective, but they may be difficult to implement in some settings because of access or transportation issues or when patients lack family or social supports. Alternative formats that eliminate or minimize access barriers are needed. Finally, studies that evaluate the effects of standardized therapies in diverse populations, such as persons with dual diagnoses, those with rapid cycling illness, and elderly persons, will expand the usefulness of psychosocial interventions to enhance adherence in a variety of clinical scenarios.

Conclusions

Treatment adherence among patients with bipolar disorder may be enhanced by interventions that address issues of appropriately taking medications to manage illness. Promotion of treatment adherence must be integrated into medication management of bipolar illness if optimum outcomes are to be achieved. The literature on the enhancement of treatment adherence for other serious mental illnesses may help in developing interventions specific to bipolar disorder. Additional studies are needed to better understand the process of adherence enhancement from a patient-centered perspective, to better measure treatment adherence, and ultimately to design ideal interventions that maximize treatment adherence and illness outcome.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University, 11100 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio, 44106-5000 (e-mail, martha.saja [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Summary of studies of interventions to enhance treatment adherence among patients with bipolar disorder

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Wyatt RJ, Henten I: An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness, 1991. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 31:213–219, 1995Google Scholar

3. Rice DP, Miller LS: The economic burden of affective disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement 27:34–42, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

4. Stender M, Bryant-Comstock L, Phillips S: Medical resource use among patients treated for bipolar disorder: a retrospective, cross-sectional, descriptive analysis. Clinical Therapeutics 24:1668–1676, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Colom F, Vieta E: Treatment adherence in bipolar patients. Clinical Approaches in Bipolar Disorders 1:49–56, 2002Google Scholar

6. Suppes T, Baldessarini RJ, Faeda GL, et al: Risk of recurrence following discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:1082–1088, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Scott J: Predicting medication non-adherence in severe affective disorders. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 12:128–130, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Muller-Oerlinghausen B, Muser-Causemann B, Volk J: Suicides and parasuicides in a high risk patient group on and off lithium long-term treatment. Journal of Affective Disorders 25:261–269, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Scott J, Pope M: Self-reported adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers, plasma levels, and psychiatric hospitalization. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1927–1929, 2002Link, Google Scholar

10. Schou M: The combat of non-compliance during prophylactic lithium treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 95:362–363, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Rapport DJ, et al: Bipolar disorders and the effectiveness of novel anticonvulsants. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63(suppl 3):5–9, 2002Medline, Google Scholar

12. Guscott R, Taylor L: Lithium prophylaxis in recurrent affective illness: Efficacy, effectiveness, and efficiency. British Journal of Psychiatry 164:741–746, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lingam R, Scott J: Treatment non-adherence in affective disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 105:164–172, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Enhancing medication compliance for people with serious mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:53–55, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Frank E, Prien RF, Kupfer DJ, et al: Implications of noncompliance on research in affective disorders. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 21:37–42, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

16. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR (eds): Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

17. Jamison KR, Gerner RH, Goodwin FK: Patient and physician attitudes toward lithium. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:866–869, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Miklowitz DJ: Longitudinal outcome and medication non-compliance among manic patients with and without mood-incongruent psychotic features. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:703–711, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Colom R, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, et al: Clinical factors associated to treatment non-compliance in euthymic bipolar patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:549–554, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Maarbjerg K, Aagaard J, Vestegaard P: Adherence to lithium prophylaxis: I. clinical predictors and patient's reasons for nonadherence. Pharmacopsychiatry 21:121–125, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Comtois KA, Ries R, Armstrong HE: Case manger ratings of the clinical status of dually diagnosed outpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:568–573, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

22. Weiss RD, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, et al: Medication compliance among patients with bipolar disorder and substance use disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59:172–174, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Schumann C, Lenz G, Berghofer A, et al: Non-adherence with long-term prophylaxis: a 6-year naturalistic follow-up study of affectively ill patients. Psychiatry Research 89:247–257, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Swartz HA, Frank E: Psychotherapy for bipolar depression: a phase-specific treatment strategy? Bipolar Disorders 3:11–22, 2001Google Scholar

25. Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, et al. Illness management and recovery: a review of the research. Psychiatric Services 53:1272–1284, 2002Link, Google Scholar

26. Cochran SD: Preventing medical noncompliance in outpatient treatment of bipolar disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 52:873–878, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Colom F, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, et al: Psychoeducation and prevention of relapse in bipolar disorders: preliminary results (abstract). Bipolar Disorders 3(suppl):32, 2001Google Scholar

28. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, et al: A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:402–407, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Clarkin JE, Carpenter D, Hull J, et al: Effects of psychosocial intervention for married patients with bipolar disorder and their spouses. Psychiatric Services 49:531–533, 1998Link, Google Scholar

30. Lam DH, Bright J, Jones S, et al: Cognitive therapy for bipolar illness: a pilot study of relapse prevention. Cognitive Therapy and Research 24:503–520, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Greenfield SF, et al: Group therapy for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence: results of a pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:361–367, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services 49:196–201, 1998Link, Google Scholar

33. Lam DH, Watkins ER, Hayward P, et al: A randomized controlled study of cognitive therapy for relapse prevention of bipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:145–162, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Miklowitz DJ, Simoneau TL, George EL, et al: Family-focused treatment of bipolar disorder:1–year effects of a psychoeducation al program win conjunction with pharmacotherapy. Biological Psychiatry 48:582–592, 2000Google Scholar

35. Shakir SA, Volkmar FR, Bacon S, et al: Group psychotherapy as an adjunct to lithium maintenance. American Journal of Psychiatry 136(suppl 4A):455–456, 1979Google Scholar

36. Perry A, Tarrier N, Morriss R, et al: Randomized controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatment. British Medical Journal 318:149–153, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Harvey NS, Peet M: Lithium maintenance: effects of personality and attitude on healthy information acquisition and compliance. British Journal of Psychiatry 158:200–204, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Van Gent EM, Zwart RM: Psychoeducation of partners of bipolar-manic patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 21:15–18, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Peet M, Harvey NS: Lithium maintenance: a standard education program for patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 158:197–200, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Mullen PD, Green LW, Persinger GS: Clinical trials of patient education for chronic conditions: a comparative meta-analysis of intervention types. Preventative Medicine 14:753–781, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Scott J: Cognitive therapy as an adjunct to medication in bipolar disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 178:164–168, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, et al: Interventions to improved medication adherence in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1653–1664, 2002Link, Google Scholar

43. Kelly GR, Scott JA: Medication compliance and health education among outpatients with chronic mental disorders. Medical Care 28:1181–1197, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Makela EH, Griffith RK: Enhancing treatment of bipolar disorder using the patient's belief system. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 37:543–545, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Sajatovic M, Davies M, Hrouda D, et al: Psychosocial intervention to promote treatment adherence among individuals with bipolar disorder treated in a community setting. Presented at the Institute on Psychiatric Services, Boston, Oct 29 to Nov 2, 2003Google Scholar

46. Scott J, Tacchi MJ: A pilot study of concordance therapy for individuals with bipolar disorders who are non-adherent with lithium prophylaxis. Bipolar Disorders 4:386–392, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Bauer MS, McBride L: Structured group psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: the Life Goals Program. New York, Springer, 1996Google Scholar

48. Bauer M: An evidence-based review of psychosocial treatment for bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 35:109–134, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

49. Lam DH, Jones S, Bright J, et al: Cognitive therapy for Bipolar Disorder: A Therapist's Concepts, Methods, and Practice. Chichester, NY: Wiley, 1999Google Scholar

50. Harvey NS: The development and descriptive use of the Lithium Attitudes Questionnaire. Journal of Affective Disorders 22:211–219, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar