A Pilot Study of Community Mental Health Care for Depression in a Supermarket Setting

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Women with depression whose diagnosis is made in community mental health clinics attend relatively few treatment sessions. A pilot project was undertaken to test the feasibility of providing psychotherapy for depressed women in a supermarket, a novel setting that may minimize barriers to care such as stigma associated with visiting a mental health clinic. METHODS: Twelve women who met DSM-IV criteria for a depressive disorder were recruited from a rural mental health clinic and offered 16 weekly sessions of supportive psychotherapy with cognitive-behavioral elements in an administrative conference room of a local supermarket. Outcomes measured were treatment attendance, depressive symptoms, and satisfaction with treatment. RESULTS: Six of the women completed the study. For the entire group, the mean number of sessions attended was 5.2. Those who completed the study attended an average of 8.7 sessions and showed significant improvement on measures of depression and anxiety. They rated their treatment experience as "very satisfactory." For the two therapists, conducting therapy in the supermarket presented some logistical problems, such as limited access to telephones and the absence of a check-in desk. The therapists also reported that providing therapy in this setting was challenging to their professional identities. CONCLUSIONS: The women in the study found treatment in the supermarket to be an appealing alternative to the mental health clinic because of greater accessibility, a perceived reduction in stigma, and convenient "one-stop shopping" for both groceries and mental health treatment.

Depression, a prevalent illness associated with considerable morbidity, affects twice as many women as men (1). Epidemiologic studies suggest that one out of five women will experience an episode of major depression during their lifetime (2). Depressive disorders are linked to high disease burden (3) and psychosocial disability (4). The disability associated with depression disappears when patients become asymptomatic (5), suggesting that adequate treatment for depression symptoms may also improve global functioning.

Although options for treating depression have expanded dramatically, depressed patients in the community often have difficulty obtaining adequate mental health care (6,7). Depressed women in particular either do not seek treatment or do not remain in treatment long enough to have even a modest chance of successful recovery (8,9). Barriers to care for women include difficulty obtaining child care and transportation, objections by significant others to the idea of entering treatment, and the social stigma associated with seeking psychiatric treatment (10,11). Women with multiple competing demands for their time may see attending to their own mental health as a self-indulgent luxury. Moreover, the effects of depression on motivation may make these obstacles difficult to overcome.

Delivering effective care to depressed women in community settings constitutes an important public health challenge. We reasoned that novel approaches may be needed to address the substantive barriers to treatment, including offering services in nontraditional settings. We therefore undertook a pilot project to test the feasibility of providing care for depressed women in a supermarket. We chose a supermarket because most women shop for food on a regular basis and might find this setting more accessible and less stigmatizing than a mental health clinic. We hypothesized that psychotherapy delivered in the supermarket would improve rates of attendance among depressed women and lead to significant reductions in their symptoms.

Methods

Participants

All research procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pittsburgh. From December 1998 through January 2000 we screened 183 women for eligibility. The women were consecutive patients who came for treatment to a community mental health clinic in a rural county in western Pennsylvania. According to 1990 census information (12), this clinic serves a county with a population of roughly 186,000 and a median income of $29,455. Women were excluded from consideration for the study if they had a psychotic disorder, an organic mental disorder, current substance abuse or dependence, or active suicidal ideation or behavior.

The 73 women who were presumed eligible were offered an evaluation for inclusion in a research study. Thirty-four women declined to participate, and two were unable to participate. We were unable to contact 13 women. Twenty-four women verbally agreed to the evaluation and were then told that the project would involve receiving treatment at a supermarket. Seven of the 24 women failed to attend the scheduled evaluation. The remaining 17 women provided written informed consent and underwent a screening assessment that included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (13). Five were determined to be ineligible for the study—three because of comorbid drug use or an organic mental syndrome and two because they did not meet criteria for a current depressive disorder.

Twelve women with a primary SCID diagnosis of a current unipolar depressive disorder, including major depressive disorder, single episode or recurrent, or depressive disorder not otherwise specified, and a depression severity score greater than 15 on the 25-item version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HRSD) (14) entered the study.

Editor's Note: This paper is part of a series on the treatment of depression edited by Charles L. Bowden, M.D. Contributions are invited that address major depression, bipolar depression, dysthymia, and dysphoric mania. Papers should focus on integrating new information for the purpose of improving some aspect of diagnosis or treatment. For more information, please contact Dr. Bowden at the Department of Psychiatry, Mail Code 7792, University of Texas Health Science Center, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, Texas 78229-3900; 210-567-6941; [email protected].

Setting and treatment

Psychotherapy was delivered in a large supermarket located six blocks from the mental health clinic and a block from a central bus terminal. The supermarket is part of a large local franchise that offers a range of products and services in addition to groceries, including video rentals, a pharmacy, a café, and child care services for children aged three to nine years. The child care services were available to all customers, including the women in our study, at no charge. Psychotherapy sessions were conducted in an administrative conference room in the back of the store.

At the mental health center, the 12 women received a physical examination, screening laboratory tests, and an assessment by a psychiatrist. Treatment consisted of 16 weeks of psychotherapy delivered in the supermarket. Sessions were scheduled weekly. Psychotherapy was delivered by one of two therapists—a licensed social worker or a registered nurse— and consisted of a supportive approach with cognitive-behavioral elements. No efforts were made to specify or modify the psychotherapy delivered. Some women were referred for concomitant pharmacotherapy by the therapists, following their usual practices, to either a psychiatrist in the mental health center or to the patient's primary care provider.

Measures

At intake, a clinician administered the SCID and the HRSD. The 12 women also completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (15), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (16), and the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) (17). At baseline they also completed a 15-item version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP), which can be used to determine the presence of a personality disorder (18). The HRSD, the BDI, the BAI, and the CSQ-8 were administered weekly. Because we hypothesized that women would find it advantageous to coordinate their grocery shopping with their psychotherapy visits, each week they were asked "Did you do any shopping while you were at the supermarket today?" A termination questionnaire (available from the authors) designed to assess responses to the treatment setting was completed at week 16. Participants received $20 grocery vouchers three times during the study—at intake, at week 8, and at week 16—to compensate them for the time required to complete the research assessments.

Statistical methods

The baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of women who left the study before week 16 and of those who completed the study were compared by using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and chi square analyses for categorical variables. For the group that remained in treatment, paired t tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to evaluate change in symptoms from baseline to week 16.

Results

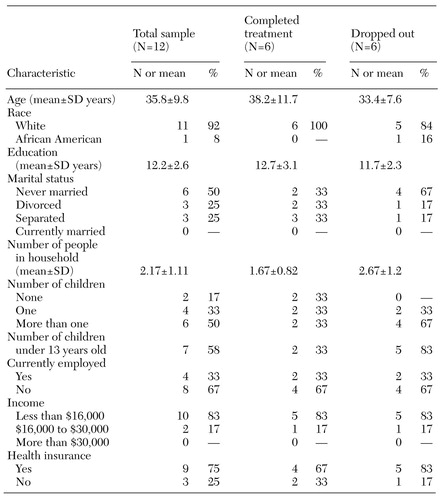

The participants' demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Eleven of the women were Caucasian, and the mean age of the group was 36. Most women had the equivalent of a high school education, and only one was currently living with a spouse or partner. Ten women had at least one child. The mean number of children was 1.7 per study participant. Most women had annual incomes of less than $16,000 and were unemployed. Most had either private or government-funded health insurance and had received some form of previous mental health treatment.

Six of the women (50 percent) remained in treatment for the entire study period and completed the termination interview at week 16, although they missed a variable number of scheduled appointments. The remaining six women dropped out before week 5. None of the dropouts completed either the midpoint or termination assessment. Among the women who dropped out, two dropped out after week 4 after either two or four sessions, two agreed to participate in the study but never came to treatment, and two refused to accept treatment in the supermarket. Among the 12 women, the mean±SD number of sessions attended, including the baseline assessment, was 5.±4.2. Those who completed the study attended a mean of 8.7±2.7 sessions (range, six to 13 sessions).

Compared with the women who completed the study, the dropouts were somewhat younger (mean age of 33 years compared with 38 years), had more children (2.2 compared with 1.2), and were more likely to have never married (67 percent compared with 33 percent). Five of the six women who dropped out had at least one child under the age of 13 years, compared with two of the six women who completed the study. In this small sample, these differences were not statistically significant.

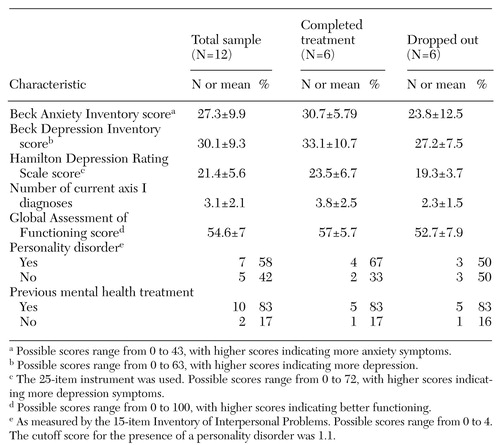

Baseline clinical characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 2. At baseline, the entire sample was moderately depressed and anxious as measured by the HRSD, the BAI, and the BDI. On the basis of a cutoff score of 1.1 on the IIP (18,19), seven women (58 percent of the sample) were presumed to have some type of personality disorder. The mean±SD baseline score on the Global Assessment of Functioning was 54.6±7. Baseline HRSD scores tended to be slightly higher in the group that completed the study (23.5±6.7 compared with 19.3±3.7), as did baseline BAI scores (30.7±5.8 compared with 23.8±12.5), but these differences were not statistically significant. For the entire sample, the mean number of current axis 1 diagnoses was 3.1±2.1. Again, the women who completed the study tended to have more axis I diagnoses (3.8±2.5 compared with 2.3±1.5), but the difference was not significant.

At baseline, seven of the women (58 percent) were taking antidepressant medication—four of those who eventually completed the study and three of those who dropped out. In the former group, two women started antidepressant therapy during the study, three switched from one antidepressant to another, and one continued taking an antidepressant prescribed before she entered the study. Thus all of the women who completed the study received antidepressant medication in conjunction with psychotherapy at the supermarket. Although we do not have follow-up data on most of the dropouts, one woman reported that she dropped out because she felt so much better when medication was started at the mental health clinic during the first week of the study that she did not wish to participate in additional psychotherapy sessions.

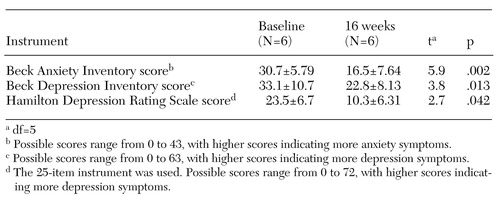

As shown in Table 3, for the group that completed treatment, symptoms improved over time. When a conservative test of significance—the Wilcoxon signed-rank test—was used, a significant drop in BAI scores was noted (W=-10.5, p=.03), as was a trend toward lower HRSD and BDI scores (W=-9.5, p=.06 for both). When a less conservative paired t test was used, a significant decline in scores on the BAI, the BDI, and the HRSD over the study period was noted.

The mean posttreatment CSQ score was 31.2±.98 out of a possible 32, indicating a high degree of satisfaction with the treatment received. In response to the CSQ item "In an overall, general sense, how satisfied are you with the service you have received?" all six women who completed the study reported that they were "very satisfied." More often than not, the women shopped at the supermarket at the time of their treatment session. During 60 percent of all visits, the women did some shopping; all of those who completed the study shopped at least once during the treatment period.

We surveyed the women who completed the study to determine their attitudes toward the supermarket. Among those who had previously received mental health treatment in a conventional setting, all preferred the supermarket to the usual treatment setting because it was "more private," "less formal," and "more convenient." One woman reported that she liked receiving psychotherapy in the supermarket because of "confidentiality; no one knew why I was there." Several women reported it helpful to "do some shopping." One woman had been seen for many years in the mental health clinic, where her attendance was notoriously erratic. In marked contrast, she attended supermarket psychotherapy sessions regularly, and the clinicians at the mental health clinic found her to be remarkably improved after she completed the study. The only complaint was from a woman who said that "it was hard to reach staff by phone."

In contrast, the psychotherapists participating in the project were much more negative about the experience of providing treatment in the supermarket setting, citing concerns about the room where psychotherapy was delivered and logistical problems such as limited access to telephones and the absence of a check-in desk. One of the therapists also reported that she felt uncomfortable practicing in a setting where she frequently shopped. Both reported that they felt "unprofessional" doing therapy in the supermarket conference room.

Discussion

This small pilot study had many limitations, and we make no claims about its validity or generalizability. However, the results of the study suggest that receiving psychiatric treatment in novel, alternative settings may appeal to some women with depressive disorders and may improve treatment attendance. Offering treatment in a setting regularly visited by individuals who have psychiatric disorders may help overcome barriers to mental health care. Below we discuss the feasibility and acceptability of conducting psychotherapy in a supermarket and identify ways in which use of this setting may help overcome barriers to mental health care that are particularly relevant to women.

Feasibility

The project showed that psychotherapy can be delivered in the conference room of a large supermarket. However, logistical difficulties were substantial. We had to convince the supermarket management to allow us to conduct the project, identify a backup system to handle medical emergencies, find a mechanism to enable therapists and patients to identify each other in the supermarket, and manage administrative functions such as scheduling appointments and maintaining medical records.

Acceptability

The women who completed the study were very satisfied with their treatment in the supermarket setting. Those who had received mental health treatment in the past preferred this setting to a conventional clinic. Thus, from the perspective of patient satisfaction, we consider our results to be quite promising. However, both of the therapists were uncomfortable delivering treatment in the supermarket. It was difficult for them to maintain their professional roles in this nonclinical setting. For example, there was no private place to write progress notes and make phone calls. Access to additional resources in the supermarket, such as a small room or cubicle, dedicated cell phones for each therapist, and enhanced peer support might reduce therapists' dissatisfaction with this setting.

Barriers to care

Because most of the women who completed the study had received mental health treatment in the past, they were able to compare this venue with previous clinical settings. The two primary advantages of supermarket psychotherapy that they identified were a reduction in stigma and the convenience of "one-stop shopping" for both groceries and mental health treatment. In effect, using a supermarket setting partly overcame two well-known barriers to care: stigma and the "time and hassle" factor. Easy access to parking and buses helped diminish transportation difficulties, another barrier to care. Few of the women used the free babysitting services, partly because their children were older or younger than the ages covered by the service—ages three to nine years.

Treatment adherence

In this pilot feasibility study, 50 percent of the participants completed the treatment protocol in the supermarket. The mean number of visits for the 12 women who participated was 5.2, and the mean number for those who completed the study was 8.7. This rate of attendance compares favorably with our previous findings at the nearby mental health clinic; in that study 47 consecutively recruited depressed women attended a mean of four treatment sessions over a three-month period (Shear MK, Swartz HA, Frank E, et al., unpublished data, 1997). However, even the women who completed the supermarket study attended only half of the scheduled sessions, which suggests that we may need to devise treatments for community settings that are even shorter than a typical brief (16-session) psychotherapy intervention.

Limitations

As stated above, this very small open trial had many limitations. First, a large number of women refused to consider participating in a research study; of 73 potential participants, only 12 entered the study. Because we were unable to collect data systematically on those who refused to participate or on those who dropped out, we do not know whether there were substantive objections among those groups to obtaining treatment in the supermarket. Second, in the absence of an appropriate control group, it is impossible to determine the relative contributions of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy to improvements in depression and anxiety scores among the women who completed the study. Pharmacotherapy may have facilitated adherence to psychotherapy. However, Alvidrez and Azocar (11) found that distressed women did not want to take antidepressant medications, preferring psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy. Thus participation in supermarket psychotherapy may have enabled women to adhere more fully to a course of medication.

Finally, because we were unable to contact the women who dropped out, we cannot compare outcomes between them and the women who completed treatment. As a group, the dropouts were slightly younger, had more young children, and were less likely to have ever married than the group that completed treatment. They also tended to have lower depression and anxiety scores at baseline and fewer comorbid axis I diagnoses. Perhaps the demands of caring for young children without a spouse interfere with treatment adherence, and some women may leave treatment if symptoms are not too intense.

Conclusions

Mental health clinic systems were not developed with the needs of overburdened women in mind. By contrast, supermarket chains have a vested interest in meeting the needs of women, who play a central role in most households in the acquisition and preparation of food. As we develop new treatments for women, we might consider the strategies of large food retailers, which are far more successful than mental health practitioners in recruiting and retaining female customers. They select accessible locations, provide services such as child care and free parking, develop products that appeal to and meet the needs of women, and provide a range of services in a single location.

Although some clinics may be in a position to institute these changes independently, other providers might consider forming alliances with retailers who would lease unused store space for nominal fees (our commercial collaborators loaned us the space free of charge). Our experience suggests that it is indeed possible to convince supermarket executives that seeking mental health treatment is no more stigmatizing than purchasing eggs and a quart of milk and that psychotherapy is as valid a service to offer in a "superstore" as video rentals or banking.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants MH-53817, MH-60473, and MH-30915 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Howard Stein, B.A., Susan Wheeler, R.N., Beverly Sullivan, M.S.W., and Kevin Camp for their invaluable assistance with this project.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O'Hara Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of women who agreed to attend 16 weeks of psychotherapy sessions in a supermarket, by whether or not they completed treatment

|

Table 2. Clinical characteristics at baseline of women who agreed to attend 16 weeks of psychotherapy sessions in a supermarket, by whether or not they completed treatment

|

Table 3. Mean±SD scores at baseline and at termination among women who completed 16 weeks of psychotherapy sessions in a supermarket

1. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al: Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 276:293-299, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, et al: Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey: I. lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders 29:85-96, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Murray CJ, Lopez AD: Evidence-based health policy: lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science 274:740-743, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hirschfeld RM, Montgomery SA, Keller MB, et al: Social functioning in depression: a review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:268-275, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Zeller PJ, et al: Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:375-380, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 277:333-340, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Klerman GL, et al: Low levels and lack of predictors of somatotherapy and psychotherapy received by depressed patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:458-466, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McGinnis JM: Health objectives for the nation. American Psychologist 46:520-524, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Van Hook MP: Women's help-seeking patterns for depression. Social Work in Health Care 29:15-34, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Aday L, Anderson R: A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Services Research 9:208-220, 1974Medline, Google Scholar

11. Alvidrez J, Azocar F: Distressed women's clinic patients: preferences for mental health treatments and perceived obstacles. General Hospital Psychiatry 21:340-347, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Pennsylvania State Data Center: Beaver County. Available at http://pasdc.hbg.psu. edu/pasdc/data_&_information/cou_profiles/c007.html, 1990Google Scholar

13. First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

14. Thase ME, Carpenter L, Kupfer DJ, et al: Clinical significance of reversed vegetative subtypes of recurrent major depression. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 27:17-22, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

15. Beck AT, Steer RA: Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1993Google Scholar

16. Beck AT, Steer RA: Manual for the Revised Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1990Google Scholar

17. Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK: The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 and the Service Satisfaction Questionnaire-30, in The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment. Edited by Maruish M. Hillsdale, NJ, Earlbaum, 1994Google Scholar

18. Pilkonis PA, Kim Y, Proietti JM, et al: Scales for personality disorders developed from the inventory of interpersonal problems. Journal of Personality Disorders 10:355-369, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Kim Y, Pilkonis PA, Barkham M: Confirmatory factor analysis of the personality disorder subscales from the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. Journal of Personality Assessment 69:284-296, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar