A Review of Interventions to Reduce the Prevalence of Parasuicide

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The author reviewed studies of treatments for parasuicide in order to assist health services planners, administrators, and clinicians develop and improve interventions for parasuicide and decrease its prevalence. METHODS: Parasuicide, which is a major risk factor for completed suicide, was defined as any nonfatal self-injury, including suicide attempts and self-mutilation. The literature from 1970 to 2001 was searched using MEDLINE and PsycINFO. Only experimental and quasi-experimental controlled trials of treatment for parasuicidal individuals were selected for review. RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS: Epidemiological research shows that parasuicide is a prevalent problem afflicting 4 to 5 percent of individuals in the United States. Parasuicide is a significant predictor of completed suicide, which is the ninth leading cause of death in the United States and accounts for 50 percent more deaths than homicide. Although research on treatments for parasuicide is limited, several treatments have received empirical support. Studies of usual care indicate that empirically supported treatments are rarely used and that standard treatments, particularly hospitalization, are very expensive. The author suggests eight practical steps, based on the literature and established health services strategies, for improving services to parasuicidal individuals. These steps are establishing case registries, evaluating the quality of care for parasuicidal persons, evaluating training in empirically supported treatments for parasuicide, ensuring fidelity to treatment models, evaluating treatment outcomes, identifying local programs for evaluation, providing infrastructural supports to treating clinicians, and implementing quality improvement projects.

Suicide is the ninth leading cause of death in the United States, and in 1996 there were 50 percent more suicides than there were homicides (31,000 compared with 20,000) (1). In response to this problem, the U.S. Surgeon General released in 1999 a Call to Action to Prevent Suicide and a National Strategy for Suicide Prevention with the explicit goal of achieving a significant decrease in suicidal behavior that is both measurable and sustainable. The Surgeon General's report identified parasuicide as a leading risk factor that can be changed or modified to prevent suicide. For the same reason, the World Health Organization identified the reduction of parasuicide as one of its targets in its Health for All program (2).

In this article parasuicide is defined as any nonfatal, self-injurious behavior with a clear intent to cause bodily harm or death (3). Thus parasuicide includes both lethal suicide attempts and more habitual or low-lethality behaviors such as cutting or other self-mutilation. This definition is not universal. Studies often use the term "suicide attempt." In other studies, suicide attempt applies only when suicide was the individual's clear intent or when the individual's behavior had a high likelihood of death. In a majority of studies, the definition is not clearly articulated (4). (In this review, the terms used will be those of the articles referenced unless otherwise specified.)

There are many responses to the problem of parasuicide. Although research on parasuicide is not extensive, significant efforts have focused on determining the prevalence of parasuicide (5), improving the accuracy of risk assessment (6), and developing and evaluating psychosocial and pharmacological treatments specific to parasuicide (4,7). This paper takes a different approach by focusing on health services planning issues to reduce the prevalence of parasuicide.

In this article health services planning is used to indicate decisions made about all patients served by a clinic or larger agency, a managed care organization, or a state mental health division. These decisions include resource allocation, use of training dollars, the structure of information systems, and mandates of particular treatments, such as best practices. Such decisions are generally made on the basis of the actual resources available plus resources that could reasonably be added rather than ideal resources that are chosen for the development of new treatments or for clinical trials.

Methods

Peer-reviewed journals were searched by using MEDLINE and PsycINFO from 1970 to 2001. Only experimental and quasi-experimental controlled trials of treatment for parasuicidal individuals were selected for review. Presentation of the results focuses on health services planning issues to reduce the prevalence of parasuicide.

Results and discussion

Overview of the problem

Before specific health services planning steps are presented, the problem of parasuicide, the literature on treatments for parasuicide, and usual care for parasuicide are reviewed. This information forms the context for the suggested steps for improving services to parasuicidal individuals.

The prevalence of parasuicide is significant. In the United States, 4.6 percent of the community sample in the recent National Comorbidity Study (8) and 4.3 percent of respondents in the earlier Epidemiology Catchment Area studies reported attempting suicide during their lifetime (9). In a review of reported suicide attempts in nine countries, Weissman and colleagues (5) found the prevalence of suicide attempts to be between 3 and 5 percent in most countries, with Beirut and Taiwan lower at .7 percent. Since parasuicide is a broader definition than attempted suicide, parasuicide rates may be higher.

Parasuicide is an established risk factor for eventual suicide. Gunnell and Frankel (10) found that 30 to 47 percent of suicide completers had a history of parasuicide and that 3 to 10 percent of suicide completers committed suicide within ten years of the first parasuicidal incident. Other studies have estimated that about half of all people who commit suicide have a lifetime history of parasuicide; 20 to 25 percent have an episode of parasuicide in the year before their deaths (11,12). A British study found that 1 percent of parasuicidal patients who were identified in general hospitals killed themselves within a year (13). Within a five- to ten-year period, the rate jumped to 3 to 5 percent. This ten-year rate of 3,000 to 5,000 per 100,000 is particularly high compared with the U.S. age-adjusted lifetime suicide rate of 10.6 per 100,000 (14).

Most research on parasuicide focuses on the risk of eventual suicide or repetition of parasuicide; little is known about the treatments received before or after parasuicide. The standard of care for parasuicide with intent to die is inpatient psychiatric services (6). Psychiatric hospitalization is common for nonlethal parasuicide as well (6), which makes parasuicide an expensive psychological problem to treat. Yeo (15) estimated treatment costs for each case of deliberate self-harm from emergency room admission to hospital discharge to be $788 in a British sample. In Sweden, Runeson and Wasserman (16) estimated that care of suicide attempters accounted for 6.4 percent of the total budget for psychiatric inpatient care at $3,620 for each admission and that the total direct management cost of suicide attempters in Sweden was $21 million per year. These costs reflect only direct medical charges—there are many other costs from lost work, social security disability, family members' lost work, and so on.

Parasuicide is also differentiated from associated comorbid diagnoses, such as depression, alcoholism, and schizophrenia, in that the standard of care for the comorbid disorder is less intensive—outpatient medications, psychosocial treatments, or residential substance abuse treatment. Thus even when parasuicide reflects an exacerbation of another disorder, its presence changes the type and intensity of the services used. These high-intensity treatments can be iatrogenic—that is, they can inadvertently increase the problem they are designed to treat (17). In the case of suicidal behavior, intense negative emotion and hopeless thinking about a difficult interpersonal or occupational problem often lead to suicidal ideation and urges to die (17,18,19). Reporting or acting on these urges may result in psychiatric hospitalization, which removes the individual from the problem situation. Hospitalization may also be soothing and may result in concrete help in solving or ending the problem. For example, staff may help the patient talk through the problem with the spouse or agree with the patient's desire to quit a stressful job. In this manner, the suicidal behavior that preceded the hospitalization is reinforced by the results of the hospitalization (relief and assistance), and suicidal ideation may be more likely to appear again in the future when a stressful event arises. Thus the acute benefit of hospitalization must be weighed against the long-term problem that suicidal behavior may be more likely in the future (17). An additional risk is that clinicians at crisis services may become habituated to repetitive parasuicide by a particular patient and respond with hospitalization or other significant help only when there is an escalation of parasuicide lethality, thus inadvertently causing an escalation of lethal parasuicidal behavior and increasing the risk of death.

Efficacy of treatments for suicide and parasuicide

Subsequent suicide. Linehan (4) examined the literature on treatments to prevent suicide. She included in her review all studies that selected subjects because they were suicidal and that applied controlled trials of treatments designed to reduce suicidal behavior among these patients compared with a control group. The studies examined suicidal ideation as well as parasuicidal acts and suicide. Eighteen of the 20 studies reviewed used random assignment, and the other two studies approximated a randomly controlled design. Linehan found no conclusive evidence that any treatment reduced suicide rates. A review by Gunnell and Frankel (10) also concluded that no single intervention has been shown to reduce suicide in a well-conducted, randomized, controlled trial. However, a more recently published study by Motto and Bostrom (20) found significantly lower suicide rates when high-risk individuals who refused further treatment were randomized to receive nondemanding letters or phone calls in which "contact was limited to expressing interest in the person's well-being"; the control group received no further contact. These results may be related to the sample being large enough (N=843) for a low-frequency behavior such as completed suicide to be detected. Nevertheless, the results suggest that further study of this innovative contact intervention along with comparably sized treatment trials is needed.

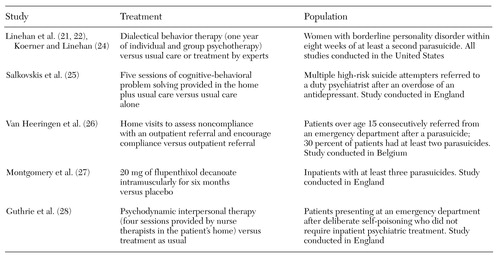

Repetition of parasuicide. Five treatments have shown significant effects in reducing the rate of repetition of parasuicide (21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28). A description of the studies can be found in Table 1. As can be seen in the table, although both the treatments and the samples included were quite different, there were commonalities. Among the four psychosocial treatments, two have a problem-solving focus. Two of the four—dialectical behavior therapy and home visits—include active attempts to address noncompliance. The other two were provided in the patient's home. The fifth trial is the only pharmacotherapy trial to show a significant main effect in reducing future parasuicide, but unfortunately the study used an antipsychotic that is not on U.S. formularies.

Several other treatment trials have been conducted that showed the experimental treatment to be no better than the control condition in reducing rates of parasuicide after admission to treatment. Hawton and colleagues (7), Linehan and coauthors (21), and van der Sande and colleagues (29) have reviewed these trials. These findings may indicate that the treatments are ineffective, but the studies were also marked by small samples, which may have led to insufficient power of detection (30). In addition, Linehan (4) has suggested that a key factor that has gone largely unnoticed is the inclusion or exclusion of high-risk patients in outcome studies of parasuicide. In the 13 outpatient studies examined in her review, Linehan found that the effectiveness of the experimental interventions compared with the control conditions was nearly uniformly predicted by whether the study included subjects at high risk of suicide. The one study that did not follow this trend did not control for the type of behavioral intervention provided. It may be that current treatments are more effective for high-risk individuals; however, this conclusion is tenuous, because these individuals are usually excluded from research studies and because small samples of lower-risk individuals may not have power to show smaller effect sizes. Thus certain treatments may be more effective than we realize, but our current research designs lack power. New treatment study designs should include high-risk patients.

Usual care of parasuicide

It is unclear to what extent usual care includes components of the treatments studied above. Only a few studies have examined service utilization before completed suicide. In Denmark, Andersen and colleagues (31) examined all suicides in a county area, finding that 13 percent of the suicide completers had been admitted to inpatient psychiatry in the previous month and 15 percent in the previous three months; 42 percent had a lifetime admission. Most patients had seen their primary care physician in the past month (64 percent), and almost all in the past year (92 percent). However, only 1 percent of individuals who committed suicide had seen a psychiatrist in the past month and 5 percent in the past year. King and Barraclough (32) conducted a comparable study in a county in England and found that 5 percent of individuals who committed suicide were hospitalized at the time of suicide and that 38 percent had been hospitalized in the past year. Outpatient psychiatric services were more common than in Denmark; 15 percent of those who committed suicide were enrolled in the National Health Service at the time of death, and 22 percent had been enrolled during their lifetime. No U.S. studies of services used before suicide have been conducted.

Studies of service utilization before and after parasuicide show wide variation by country, date of study, and age group. For instance, some outpatient service was used by 19 to 57 percent of patients in the month before parasuicide (26 to 81 percent lifetime) (16,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43). However, none of these studies are of U.S. samples. Thus at this time, we know little about the usual care provided to parasuicidal individuals in the United States. It is likely that the severity of the problem varies widely, and more intensive or longer treatments (44) would not be necessary for all parasuicidal individuals. In addition, the usual care may not reflect these differing intensities. That is, there may be inefficiencies in the system in which patients receiving the most intensive services and those needing such services are not the same.

Although usual care for parasuicide per se has not been studied, depression, a common diagnosis among parasuicidal individuals, has been examined. It has been shown that usual care for depressed primary care patients does not generally follow the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research recommendations about the frequency of contact, dosages, or duration of antidepressant medications or specific evidence-based psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (45).

Two studies in Finland have used a quality-of-care model to evaluate treatment provided immediately before and after a parasuicide based on their own quality standards for the pharmacotherapy of depression. Suominen and colleagues (35,36) examined the treatment of two groups of persons who attempted suicide (N=114), one with major depression and one with alcoholism, in the month before and the month after the index parasuicide. The definition of suicide attempt was the same as the definition of parasuicide used in this paper. In the month before the parasuicide, 65 percent of the depressed patients and 51 percent of the alcoholic patients received some medical or psychiatric care; 88 percent of the depressed patients and 64 percent of the alcoholic patients received care after the parasuicide.

The authors concluded from a review of treatment received for depression that the vast majority of patients did not receive adequate treatment for depression either before or after the parasuicide. No treatment specific to parasuicide was reported. Noncompliance cannot explain this result, because 93 percent of suicide attempters were referred to inpatient or outpatient aftercare treatment, and only one referred patient did not attend aftercare. Although the quality of care was not evaluated for the alcoholic patients, the authors concluded that there was little change in the frequency or quantity of treatment provided after the parasuicide.

Compliance with aftercare was lower for alcoholic suicide attempters. Only 74 percent of patients received an inpatient or outpatient aftercare referral, of whom 82 percent attended that referral. Referrals varied from advice to seek care to referral to a specific agency, a fixed appointment, voluntary inpatient treatment, and involuntary inpatient treatment. Active referral—that is, more than advice—was associated with compliance among both depressed and alcoholic suicide attempters. These data suggest that usual care for parasuicide could be substantially improved.

Practical steps

Clearly more research is needed on treatments for suicide prevention. Equally clearly, many suicidal individuals are not receiving the help they need now. Fortunately, many strategies in the health services literature can be applied to planning services to prevent suicide. Eight practical steps based on the suicide treatment and health services literature are described in this section.

Establish case registries. Data are now available nationally and internationally on the prevalence of suicide (the ninth leading cause of death) and parasuicide (a lifetime prevalence of close to 5 percent) in community samples. However, further research is needed on parasuicide among patients receiving mental health care, for whom the rate is likely to be higher. To do this, case registries that specifically identify and include parasuicide or other relevant risk factors as variables are needed. For instance, many information systems or other state reporting systems identify dangerousness (including both suicidal and homicidal behavior) or suicidality (including suicidal ideation and threat as well as parasuicide), which confuses the identification of cases. Research on suicide clearly indicates that parasuicide is the best predictor (30) and that suicidal ideation, with a lifetime prevalence of more than 40 percent in community samples, is not as useful. Therefore, carefully crafted indicators for parasuicide and other risk factors are needed with enough specificity as well as sensitivity.

Evaluate quality of care. Evaluation of the quality of care involves establishing practice guidelines that are then applied as program evaluation tools. The paucity of efficacy research limits the ability to establish specific practice guidelines for parasuicide treatment. However, guidelines that can be developed immediately include suicide risk assessment, for which there is a significant empirical research base; treatment guidelines for disorders comorbid with parasuicide—depression, schizophrenia, and alcoholism—for which there is also a research base (46,47,48,49,50); and general behavioral health standards that apply to all disorders, such as keeping an outpatient appointment within seven or 30 days after inpatient psychiatric discharge. Such guidelines have been developed by the National Council for Quality Assurance for evaluation of health maintenance organizations.

Evaluate training. Training in empirically supported treatments for parasuicide needs to be available and generally is not. In addition, little research has been done to evaluate the effectiveness of training programs for empirically supported treatments. Such training research would ensure that treatments could be taught efficiently, which is critical to systems that need to make large investments of both time and money to train staff in new treatments. In the area of suicide interventions, Hawkins and Sinha (51) reported on a dialectical behavior therapy dissemination program in Connecticut in which colleagues of Linehan trained clinicians at mental health centers. In their study, the ability of the staff to understand the concepts of dialectical behavior therapy was evaluated by use of a questionnaire. Results indicated that a public-sector pool of clinicians was able to acquire solid grounding in dialectical behavior therapy theory in a relatively brief time and that grounding was related to the amount of training conducted by participants themselves (reading or study groups) as much as by expert consultation. Rigorous outcomes data were not yet available, but pilot data indicated that patients treated with dialectical behavior therapy used less emergency services, had fewer inpatient admissions, and spent less time in restraint or seclusion (51). No training research has been documented for other parasuicide treatments.

In some cases, such training will be too costly given staff turnover or given the level of staff training necessary to approximate the training of clinicians in the efficacy trials. It will often then be more cost-effective for systems to hire staff with the appropriate training, even when such individuals are quite different from those typically hired (psychotherapists compared with case managers).

Evaluate fidelity to treatment models. Training does not ensure that clinicians and agencies are conducting the treatment as it was designed. However, treatment manuals and training are often provided with measures of fidelity to the treatment model. Such fidelity measures are useful for evaluating the effectiveness of training and for assisting clinicians who are training themselves to do the treatment well enough to expect outcomes comparable to those in the effectiveness trials. However, fidelity presents a serious quandary. Successful implementation of a treatment requires that the treatment be acceptable to the setting—often dictating substantial adaptation of the treatment. Just as a medication is useless unless the patient takes it, effective treatments will also be useless unless they are adopted by the systems for which they are designed. On the other hand, the solution to a patient's lack of adherence to a therapeutic dosage of a prescribed medication is not to lower the dosage until the patient is willing to take it or the doctor prescribe it, which would render the medication ineffective. Compliance with an ineffective medication is equally useless. Thus a synthesis is needed, such that the treatment works in the setting in which it is needed but remains consistent enough with the research model that it keeps its effect.

Successful and unsuccessful examples have been seen in implementing assertive community treatment models for schizophrenia. Some adaptation has been required, but research indicates that certain adaptations have resulted in decreased fidelity to the original model and associated poorer treatment outcomes (52,53,54,55). The fidelity of suicide interventions will need to be evaluated to ensure that we understand and do not leave out the most critical parts of the treatments.

Evaluate outcomes. Once a treatment is implemented, some regular evaluation of outcome is needed. Outcomes of treatment for suicidal behaviors can be evaluated if case registries are appropriately designed and factors such as parasuicide, cause of death, use of outpatient and crisis services, and costs of treatment can be easily evaluated. Several reliable and valid measures of quality of life and psychopathology are also available—Lehman's Quality of Life Interview (56), the Brief Symptom Inventory (57), and the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale (58). These measures can be included as part of routine reporting or used separately in a program evaluation.

Evaluate local programs. Treatments developed and evaluated by academics are unlikely to be the only efficacious treatments available. Model programs that may be quite effective in preventing parasuicide are operating throughout the mental health system. Programs that local stakeholders such as clinicians, advocates, and administrators believe to be effective should be evaluated and compared with treatment as usual. When model programs are shown to be effective, manuals need to be developed and the results published in order to foster dissemination. An example for parasuicide is the partial hospitalization program developed for borderline personality disorder by Bateman and Fonagy (59,60) in London, which has shown positive outcomes for parasuicide as well as borderline personality disorder.

Provide infrastructural supports. A myriad of infrastructural supports can help with implementation. Recording of data elements such as parasuicide for a case registry increases awareness locally and also inform the larger system. Given the common finding in efficacy studies that several treatments for parasuicide focusing on noncompliance have stronger outcomes, feedback could be provided to referring clinicians about their client's attendance at the referred treatment and to others responsible for the client (primary care providers) about the patient's follow-through. Decision trees regarding suicide risk assessment or treatment of comorbid psychiatric disorders might be helpful in guiding the treatment decisions of clinicians who do not have special training in the area of suicide. Ticklers or other reminders of whether the patient has received high-quality treatments might help providers know when extra time or effort is needed.

For example, when a suicidal patient is hospitalized, a computerized tickler with the discharge date could trigger the clinician to ensure that an outpatient appointment is available, and further reminders could be sent if the patient has not kept the appointment within seven days and 30 days. In some medical and mental health centers, chart note templates that specify empirically supported suicide risk factors are required for documentation when a patient reports significant suicidal ideation or behavior. Use of these templates ensures a complete assessment, and repeated use helps clinicians recall all the risk factors.

Implement quality improvement.Finally, quality improvement projects that address identified weaknesses in the system use now-familiar mechanisms of continuous quality improvement and quality assurance to improve care. Such systems are built into most local agencies and can be used to incrementally improve services to parasuicidal individuals using any of the above options.

Conclusions

Parasuicide is a major concern in the general population, but particularly for the mental health system. Although few efficacy trials have been conducted, patterns of successful treatments are highlighting the strength of psychosocial treatments, particularly interventions that target attendance as an explicit part of treatment or provide treatment in the patient's home. Only one of these treatments, dialectical behavioral therapy, has moved beyond efficacy trials. Systematic training in this treatment approach is being provided to community agencies, and the results are being reported. It is critical for other treatments to follow the same path because dialectical behavior therapy is a large, complex, and lengthy treatment, and it is probably more treatment than is needed in many cases. The combination of empirical support with replication and availability of training in the model have made dialectical behavior therapy stand out as a parasuicide treatment at this time.

Improved outcomes and decreased prevalence of parasuicide will also rely on more active steps by local and larger systems of care. Several practical steps are suggested in this paper to facilitate progress in this area. However, progress will be slow. Parasuicide is not easily treated, and repeated parasuicide results in burnout for consumers, providers, and families. Progress can be accelerated by using advances in dissemination of treatments for other disorders, creating momentum to improve health services for parasuicide, reduce its prevalence, and thus prevent suicide.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Wayne Katon, M.D., Marsha Linehan, Ph.D., Peter Roy-Byrne, M.D., Richard Comtois, Ph.D., and Doug Zatzick, Ph.D., for their assistance in the conceptualization of these issues and for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Dr. Comtois is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Harborview Medical Center, 325 Ninth Avenue, Box 359911, Seattle, Washington 98104 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Comparison of treatments demonstrated in randomized trials to reduce repetition of parasuicide

1. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent Suicide. Washington, DC, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

2. Schmidtke A, Bilk-Brahe V, Deko D, et al: Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends, and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989 to 1992. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 93:327-338, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kreitman N: Parasuicide. Chichester, England, Wiley, 1977Google Scholar

4. Linehan M: Behavioral treatments of suicidal behaviors: definitional obfuscation and treatment outcomes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 836:302-328, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al: Prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempts in nine countries. Psychological Medicine 29:9-17, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bongar B, Berman AL, Maris RW, et al: Risk Management With Suicidal Patients. New York, Guilford, 1999Google Scholar

7. Hawton K, Arensman E, Townsend E, et al: Deliberate self-harm: systematic review of efficacy of psychosocial and pharmacological treatments in preventing repetition. British Medical Journal 317:441-447, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters E: Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:617-626, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Moscicki EK, O'Carroll P, Rae DS, et al: Suicide attempts in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 61:259-268, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gunnell D, Frankel S: Prevention of suicide: aspirations and evidence. British Medical Journal 308:1227-1233, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Ovenstone IM, Kreitman N: Two syndromes of suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry 124:336-345, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R: Mental disorders and suicide in Northern Ireland. British Journal of Psychiatry 170:447-452, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hawton K, Fogg J: Suicide, and other causes of death, following attempted suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry 152:751-761, 1988Google Scholar

14. National Center for Health Statistics: Vital Statistics of the United States, vol II, Mortality: Part A. Technical Appendix. Hyattsville, Md, Public Health Service, 1997Google Scholar

15. Yeo HM: The cost of treatment of deliberate self-harm. Archives of Emergency Medicine 9:8-14, 1992Google Scholar

16. Runeson B, Wasserman D: Management of suicide attempters: what are the routines and the costs? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 90:222-228, 1994Google Scholar

17. Linehan MM: Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

18. Ivanoff A, Smyth NJ, Grochowski S, et al: Problem solving and suicidality among prison inmates. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:970-973, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Schotte DE, Clum GA: Problem solving skills in suicidal psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55:49-54, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Motto JA, Bostrom AG: A randomized controlled trial of postcrisis suicide prevention. Psychiatric Services 52:828-833, 2001Link, Google Scholar

21. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:1060-1064, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Linehan M, Tutek D, Heard H, et al: Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1771-1776, 1994Link, Google Scholar

23. Koons CR, Robins CJ, Tweed JL, et al: Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy 32:371-390, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Koerner K, Linehan MM: Research on dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 23:151-167, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Salkovskis P, Atha C, Stover D: Cognitive-behavioural problem solving in the treatment of patients who repeatedly attempt suicide: a controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 157:871-876, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Van Heeringen C, Jannus S, Buylaca W, et al: The management of non-compliance with referral to outpatient after-care among attempted suicide patients: a controlled intervention study. Psychological Medicine 25:963-970, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Montgomery SA, Montgomery DB, Jayanthi-Rani S, et al: Maintenance therapy in repeat suicidal behavior: a placebo controlled trial, in Proceedings of the Tenth International Congress for Suicide Prevention and Crisis Intervention Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 1979Google Scholar

28. Guthrie E, Kapur N, Mackway-Jones K, et al: Randomised controlled trial of brief psychological intervention after deliberate self poisoning. British Medical Journal 323:1-5, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Van der Sande R, Buskens E, Allart E, et al: Psychosocial intervention following suicide attempt: a systematic review of treatment interventions. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 96(1):43-50, 1997Google Scholar

30. Pearson J, Hendlin HH: Treatment Research Workshop on Suicide. Sponsored by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and National Institute of Mental Health, Washington, DC, Mar 17-18, 1999Google Scholar

31. Andersen U, Andersen M, Rosholm J, et al: Contacts to the health care system prior to suicide: a comprehensive analysis using registers for general and psychiatric hospital admissions, contacts to general practitioners and practising specialists, and drug prescriptions. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 102:126-134, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. King E, Barraclough B: Violent death and mental illness: a study of a single catchment area over eight years. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:714-720, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT, et al: Prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders in persons making serious suicide attempts: a case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1009-1014, 1996Link, Google Scholar

34. Chastang F, Rioux P, Kovess V, et al: Epidemiological study of patients and self-attempters admitted in a psychiatric emergency. Revue d'Epidemiologie et Santé Publique 44:427-436, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

35. Suominen KH, Isometsa ET, Hennksson MM, et al: Treatment received by alcohol-dependent suicide attemp-ters. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 99:214-219, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Suominen KH, Isometsa ET, Henriksson MM, et al: Inadequate treatment for major depression both before and after attempted suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1778-1780, 1998Link, Google Scholar

37. Suokas J, Loennqvist J: Selection of patients who attempted suicide for psychiatric consultation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 38:179-182, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Hall R, Platt D, Hall R: Suicide risk assessment: a review of risk factors for suicide in 100 patients who made severe suicide attempts: evaluation of suicide risk in a time of managed care. Psychosomatics 40:18-27, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Bagley C, Greer S: Clinical and social predictors of repeated attempted suicide: a multivariate analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry 119:515-521, 1971Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Brauns ML, Berzewski H: Follow-up study of patients with attempted suicide. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 34:285-291, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Hankoff LD: Categories of attempted suicide: a longitudinal study. American Journal of Public Health 66:558-563, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Perez E, Minoletti A, Blouin J, et al: Repeated users of a psychiatric emergency service in a Canadian general hospital. Psychiatric Quarterly 58:189-201, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Trautman PD, Stewart N, Morishima A: Are adolescent suicide attempters noncompliant with outpatient care? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32:89-94, 1993Google Scholar

44. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:1060-1064, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Lin EHB, Von Korff M, Katon WJ, et al: Depression Outcomes and Service Use in Primary Care: A Needs Assessment of Individualized Stepped Care. Seattle, Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Center for Health Studies, 2000Google Scholar

46. Schulberg HC, Katon W, Simon G, et al: Treating major depression in primary care practice. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:1121-1127, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al: Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:611-617, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Treatment of Depression: Newer Pharmacotherapies. Pub 99-E014. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1999Google Scholar

50. Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Dependence. Publ 99-E004. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1999Google Scholar

51. Hawkins KA, Sinha R: Can line clinicians master the conceptual complexities of dialectical behavior therapy? An evaluation of a state department of mental health training program. Journal of Psychiatric Research 32:379-384, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Essock SM, Kontos N: Implementing assertive community treatment teams. Psychiatric Services 46:679-683, 1995Link, Google Scholar

53. McGrew JH, Bond GR, Dietzen L, et al: Measuring the fidelity of implementation of a mental health program model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:670-678, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. McGrew VH, Bond GR: The association between program characteristics and service delivery in assertive community treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 25:175-189, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. McHugo GV, Drake RE, Teague GB, et al: Fidelity to assertive community treatment and outcomes in the New Hampshire dual disorders study. Psychiatric Services 50:818-824, 1999Link, Google Scholar

56. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

57. Derogatis LR: The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures. Manual II, 2nd ed, Baltimore, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1992Google Scholar

58. Bigelow LB, Berthot BD: The Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale (PSAS). Psychopharmacology Bulletin 25:168-173, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

59. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1563-1569, 1999Link, Google Scholar

60. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: an 18-month follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:36-42, 2001Link, Google Scholar