Community Placement of Long-Stay Psychiatric Patients in Northern Finland

Abstract

Rapid deinstitutionalization occurred in Finland in the 1990s, a decade later than in many other Western countries. A four-year follow-up study in northern Finland examined community placements of 253 long-stay psychiatric inpatients after deinstitutionalization in 1992 and at follow-up at the end of 1995. About 70 percent of the patients were discharged. Only 15 percent were able to live outside the hospital without continuous support. No patient was homeless at follow-up. Being unmarried, living in the city of Oulu, and having greater severity of illness were associated with hospitalization at follow-up. The results showed that long-stay patients are dependent on considerable support. Alternative residential facilities have made deinstitutionalization possible.

Psychiatric hospital care has been subject to fundamental deinstitutionalization over the past four decades in Western Europe and the United States. In Finland this process has been delayed about ten years and has occurred mainly in the 1990s (1,2,3). In 1993 legislation in Finland reduced state subsidies for counties, making it no longer economically feasible for them to hospitalize psychiatric patients. The result was to hasten the deinstitutionalization process.

During the last decade, deinstitutionalization has occurred in the catchment area of Oulu University Hospital in northern Finland. The city of Oulu has about 117,000 residents. The total number of psychiatric beds decreased markedly: from 962 beds in 1985 to 594 beds in 1991, then 425 beds in 1992, and 235 beds in 1996.

Our main interest was to learn where long-stay psychiatric inpatients had been placed as a consequence of the rapid deinstitutionalization process in northern Finland. The main questions were, Where were patients placed after their last hospital discharge in 1992, and where were they at the end of a four-year follow-up period? What clinical and sociodemographic factors predicted hospitalization at the end of the follow-up? In addition, we examined gender differences in placements at discharge and follow-up.

Methods

The study was part of a four-year follow-up of 253 long-stay psychiatric inpatients who were hospitalized without a break (the index hospitalization) for six months or more between January 1 and December 31, 1992, in the department of psychiatry at Oulu University Hospital. The subjects were 157 males and 96 females.

Patients were identified from a computerized patient register and case records, and clinical data were obtained from these sources. The follow-up began at the end of the index hospitalization in 1992 and ended on December 31, 1995, or on the date of a patient's death. Data on sociodemographic variables were collected from the case records at the beginning of the index hospitalization. A detailed description of the data and the variables is presented elsewhere (4).

Diagnoses were based on DSM-III-R criteria. Of the 253 patients, 203 (80.2 percent) had schizophrenia, 13 (5.1 percent) had other functional psychoses, 24 (9.5 percent) had organic disorders, six (2.4 percent) had personality disorders, and seven (2.8 percent) had mood disorders.

The placement after the patients' last hospital discharge during the follow-up and at the end of the follow-up was identified from the computerized patient register and case records or obtained directly from staff in the last inpatient ward where the patient was known to have been hospitalized.

Results

The results indicated that 177 of the 253 patients (70 percent) were discharged. Only 38 patients (15 percent) were able to live on their own, at home or in supported lodging, without daily support from professional staff.

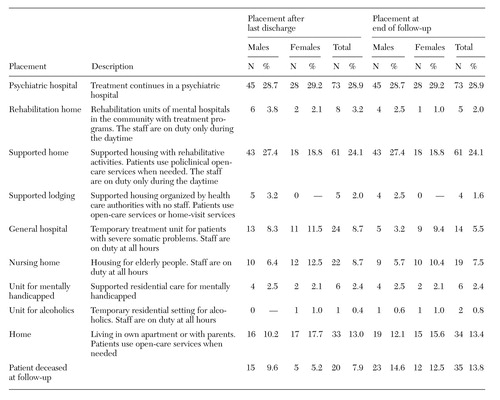

Table 1 presents a brief description of patients' placements after their last discharge during and at the end of the follow-up. After the last discharge, a greater proportion of men were placed in rehabilitation or supported homes; 49 men (31.2 percent) and 20 women (20.8 percent) had such placements. At discharge a greater proportion of women were placed in other institutions, including hospitals for the treatment of physical illnesses, nursing homes, and units for mentally handicapped people or alcoholics; 26 women (27.1 percent) and 27 men (17.2 percent) had such placements. About an equal proportion of men and women were discharged to live at home or in supported lodgings: 21 men (13.4 percent) and 17 women (17.7 percent). At discharge, the proportion of deceased men was slightly higher than that of women; 15 men (9.6 percent of men) and five women (5.2 percent of women) were deceased.

At the end of the follow-up, the distribution of placements was almost identical to the distribution after the last discharge during the follow-up. No statistically significant gender differences were found in the distribution of the placements after the last discharge or at the end of the follow-up.

Because some of the variables had skewed or limited distributions, a logistic regression analysis was used to assess the probability of hospitalization after the most essential clinical and sociodemographic variables were adjusted. The results indicated that several variables increased the probability of hospitalization at the end of the follow-up period. They were not being married (odds ratio=14.2, 95 percent confidence interval=1.2 to 170.5); living in the city of Oulu (OR=2.6, CI=1.2 to 5.5); absence of negative symptoms (OR=2.5, CI=1.1. to 5.8); a Global Assessment Scale score of less than 30 (OR=4.6, CI=1.5 to 14.5); and a high dosage of neuroleptic medication, either 301 to 600 mg chlorpromazine equivalents (OR=2.6, CI=1 to 6.8) or more than 600 mg chlorpromazine equivalents (OR=3.4, CI=1.2 to 9.2).

The proportion of days spent in inpatient care between the first psychiatric admission and the beginning of the index hospitalization was also a predictor of hospitalization at follow-up. For 25 percent to 50 percent of days in inpatient care the odds ratio was 6.8 (CI=1.7 to 27.7), for 51 percent to 75 percent of days it was 5.2 (CI=1.1 to 24.9), and for more than 75 percent of days it was 7.3 (CI=1.6 to 33.6). No other variables were significantly related to hospitalization at follow-up, including gender, number of children, accommodations, age, positive and depressive symptoms, social functioning measured with the Strauss-Carpenter Scale, number of involuntary hospitalizations, and number of psychiatric hospitalizations.

Discussion

The main finding of our study was that about 70 percent of 253 long-stay patients were successfully discharged from the hospital, and that most were discharged to residential facilities. Only 15 percent of the sample were able to live without daily professional support. At follow-up, none of the study participants were homeless, which is a finding of other studies of deinstitutionalized psychiatric patients (5).

Our findings indicate that a successful decrease in the use of psychiatric hospital care among chronically ill patients is possible only if alternative types of residential care are available. This conclusion is also supported by the finding that living in the city of Oulu was an independent predictor for hospitalization at the end of the follow-up. At follow-up many of the long-stay patients registered as residents of Oulu were still being treated traditionally in the hospital. However, the strategy used to reduce costs of psychiatric care among long-stay patients differed for patients from smaller counties with fewer resources, a greater proportion of whom were moved to alternative treatment placements.

Of the other significant predictors of hospitalization, not being married highlights the importance of the social support patients obtain from their families to survive in the community. Low Global Assessment Scale scores, high dosages of antipsychotic medication, and longer duration of hospital care before follow-up characterized the most severely ill patients, who were more likely to be hospitalized at follow-up. This finding highlights the rational use of psychiatric hospital care in northern Finland: the most seriously ill patients get the most intensive care. An absence of negative symptoms predicted hospitalization, perhaps because patients who exhibit mostly negative symptoms can more easily be treated in other treatment settings with fewer staff.

The distribution of placements remained very much the same after the last discharge in 1992 until the end of the follow-up in 1995. Between these two time points only minor changes in the placements were noted. In this respect, the deinstitutionalization process has been successful—the choices of the placements have been reasonable.

More men than women were hospitalized at follow-up, but gender itself did not predict hospitalization. The excess of men can be accounted for by the better outcomes observed for women with schizophrenia (6).

New kinds of treatment units with more and better-educated staff are necessary if the deinstitutionalization process is to continue. Long-stay psychiatric patients nowadays are increasingly ill and depend on considerable support. Furthermore, in the process of deinstitutionalization a too-rapid reduction of hospital beds may lead to repeated hospitalizations, problems in living, and social isolation (2,7).

Although further development of alternative treatment settings could be more expensive than providing hospital care (8,9), the alternatives may be more humane. One should keep in mind that assessments of the overall cost of schizophrenia must take into account the cost to the patient and the cost to the family, including suffering and loss of productivity (10). Changes in the treatment culture have preceded the deinstitutionalization process, and the economic situation of society has added speed to it. However, the ongoing changes and developments in psychiatric care must not be dependent on financial factors alone.

Except for Dr. Nieminen, the authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Oulu, Peltolantie 5, FIN90210 Oulu, Finland (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Nieminen is with the medical computing unit at the university.

|

Table 1. Placement of 253 long-stay psychiatric patients in northern Finland after their last hospital discharge during the follow-up period (1992–1995) and at the end of the follow-up in 1995, by gender

1. Rafter J: Mental health services in transition: the United States and the United Kingdom. British Journal of Psychiatry 161:589-593, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lamb HR: Lessons learned from deinstitutionalisation in the US. British Journal of Psychiatry 162:587-592, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Tuori T, Lehtinen V, Hakkarainen A, et al: The Finnish national schizophrenia project 1981-87:10-year evaluation of its results. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 97:10-17, 1998Google Scholar

4. Räsänen S, Hakko H, Herva A, et al: Gender differences in long-stay psychiatric inpatients: observations from northern Finland. International Journal of Mental Health 28:69-85, 1999Google Scholar

5. Leff J: All the homeless people: where do they all come from? British Medical Journal 306:669-670, 1993Google Scholar

6. Angermeyer ML, Kuhn L, Goldstein JM: Gender and the course of schizophrenia: differences in treated outcomes. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:293-307, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Leff J: Problems of transformation. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 38:16-23, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Häfner H, an der Heiden W: Evaluating effectiveness and cost of community care of schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:441-451, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Goldberg D: Cost-effectiveness studies in the treatment of schizophrenia: a review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 26:139-142, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Andreasen NC: Assessment issues and the cost of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:475-481, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar