Use of Health Services by Men With and Without Antisocial Personality Disorder Who Are Alcohol Dependent

Abstract

In a sample of 104 medically stable male veterans with alcohol dependence, rates of health service utilization were compared for 48 patients with a primary diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder and 56 patients without this diagnosis. Patients were diagnosed using DSM-IV lifetime criteria; previous utilization of health services was based on self-reports. Although a similar proportion of both groups reported previous service use, patients with antisocial personality disorder reported using more substance abuse treatment services than those with a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence. Between-group multiple regression analysis showed that an earlier age at onset of alcoholism and a history of a comorbid substance-induced mental disorder best predicted higher rates of use of substance abuse treatment.

Alcoholics are among the highest-cost users of medical care in the United States (1). This high rate of service utilization has been correlated with severity of alcohol-related problems, especially among alcoholics with comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders (2,3,4).

Comorbidity appears to influence service utilization by alcohol-dependent patients in two ways. First, having a comorbid psychiatric condition influences when patients seek treatment and the types of treatment used (5). Second, having a comorbid psychiatric disorder such as depression, antisocial personality disorder, or a drug use disorder negatively affects treatment outcome (2,6) and is associated with higher rates of inpatient readmission (6).

To date, studies identifying factors influencing service utilization have focused on patients' demographic characteristics, such as age, race, and marital status, and on more global assessments of severity of illness (2,6). However, much less is known about specific comorbid disorders that might drive increases in health service utilization. For example, only a few studies examining rates of health service use among alcoholics have controlled for specific psychiatric syndromes such as antisocial personality disorder (3), abuse of or dependence on other drugs (3,7), and substance-induced mental disorders (8). When studies have controlled for these conditions, most have not formally diagnosed patients according to DSM criteria but rather have relied on hospital records for discharge diagnoses (2,6,9). Such information may not adequately characterize the patients under investigation and may have even underestimated the rates of alcohol dependence in some settings (7).

In this study, we investigated differences in service utilization between medically stable alcohol-dependent men with and without comorbid antisocial personality disorder. We examined the quantity and frequency of service use and used standardized diagnostic criteria to determine whether subjects differed in their rates of health services utilization. We hypothesized that patients with comorbid antisocial personality disorder and alcohol dependence would use more health services than patients with alcohol dependence who did not have antisocial personality disorder.

Methods

Subjects

Male and female veterans between the ages of 18 and 55 years seeking inpatient treatment in the alcohol and drug treatment program at the San Diego Veterans Affairs Medical Center between September 1993 and May 1996 were screened for possible inclusion in the study. Because the aim of the study was to determine biological differences between alcoholics with and without antisocial personality disorder, patients were excluded if they had a history of an independent axis I disorder other than substance abuse or dependence or a major medical illness, if they were taking psychoactive medications, or if they were leaving the San Diego area immediately after discharge.

The sample consisted of 104 men with a diagnosis of substance dependence or abuse, 48 of whom had a comorbid diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder and 56 of whom did not. The sample of 104 represents 62 percent of the total number of male subjects who met initial inclusion criteria for the study; it does not include the healthy volunteers and the subjects with antisocial personality disorder but without an alcohol-related diagnosis who participated in the larger study (Anthenelli RM, Maxwell RA, unpublished manuscript, 1999).

Procedures

Subjects were interviewed by a trained research assistant using a semistructured interview that collects information on subjects' demographic characteristics and personal histories of alcohol and drug use, psychiatric problems, and health services utilization. The interview conforms to the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for abuse of and dependence on alcohol and eight other drug categories and assesses ten other axis I disorders, antisocial personality disorder, and substance-induced psychiatric disorders. A similar interview was conducted with a collateral informant who was usually a close relative, spouse, or friend.

Because alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder affect men more than women (5), and because the VA treatment population is primarily male, sufficient data for analysis were available only for men. The subjects were classified into two diagnostic groups—those with a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence and those with primary antisocial personality disorder with secondary alcoholism. The diagnoses were based on clinical history and determination of the age at onset of symptom clusters (10). Primary alcoholism connotes that an individual developed alcohol dependence before the onset of any other psychiatric disorder. Primary antisocial personality disorder with secondary alcoholism indicates that an individual exhibited a pattern of irresponsibility and violating the rights of others—that is, fulfills the DSM-IV criteria for conduct disorder—before the onset of alcohol dependence (Anthenelli RM, Maxwell RA, unpublished manuscript, 1999).

Health service utilization was determined for both groups based on use of substance abuse and mental health treatment before the index hospitalization. Use of services was measured by the number of separate lifetime admissions to a detoxification unit, inpatient or outpatient substance abuse rehabilitation, or an inpatient psychiatric unit. Outpatient mental health contacts were measured by the number of therapy sessions attended. Attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and other forms of informal support were not included in the analysis.

Differences between diagnostic groups were examined using nonparametric tests (chi square analysis, Mann-Whitney U test, and Fisher's exact test) for categorical variables or for skewed data, and parametric tests (t test) were used for normally distributed variables. Multiple regression was used to determine which variables best predicted the rate of health service utilization. The variables examined were age at onset of alcohol dependence, marital status, age at interview, history of substance-induced mood disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and any drug dependence disorder.

Results

The two diagnostic groups—primary alcoholics and antisocial alcoholics—were similar in age, with mean±SD ages of 39.4±9.2 years and 37.8±8.8 years, respectively. The racial composition of both groups was similar; Caucasians constituted 79 percent (N=44) of the primary alcoholic group and 77 percent (N=37) of the antisocial alcoholic group. Overall, 37 of the primary alcoholics (63 percent) and 39 of the antisocial alcoholics (69 percent) reported receiving previous substance abuse treatment.

A trend was noted for a greater proportion of antisocial alcoholics than primary alcoholics to use mental health services (43 percent versus 28 percent; p<.09). Compared with the men who had primary alcohol dependence, the antisocial alcohol-dependent men tended to be unmarried (18 percent versus 4 percent married; χ2=4.75, df=1, p<.03), to have an earlier age at onset of alcohol dependence (25±6.8 years versus 20±6 years; t=3.87, df=101, p<.001), to have an earlier age at first mental health treatment contact (33.4±8 years versus 24.8±10.1 years; t=2.68, df=33, p<.02), and to report using a greater variety of illicit drugs (3.8±2.7 drugs versus 5.9±1.9 drugs; t=−4.79, df=97, p<.001).

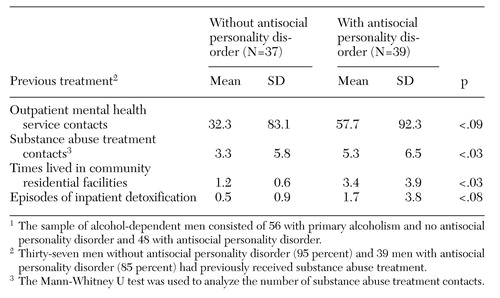

In the second stage of analysis, subjects reporting no treatment history before study entry were excluded, resulting in a sample size of 76 alcoholic men, 37 with primary alcoholism and 39 with antisocial personality disorder. As shown in Table 1, among subjects who reported previous use of substance abuse or mental health services, no significant differences were found between groups in the proportion that had ever sought substance abuse treatment. However, the antisocial alcohol-dependent men used substance abuse treatment services more frequently (Z=−2.14, p<.04), with more frequent stays in community residential facilities for alcoholics (t=−2.43, df=18, p<.03). A trend was also noted for antisocial alcoholics to have had more episodes of inpatient detoxification (t=−1.83, df=42, p<.08).

Although the antisocial alcoholic group reported more polysubstance use than primary alcoholics, multiple regression analysis demonstrated that two factors, age at onset of alcohol dependence and a history of comorbid substance-induced depression, best predicted higher rates of use of substance abuse treatment (R2=.14). After the analysis accounted for these variables, other variables entered in the regression equation did not explain any additional unique variance. They were the use of other drugs and diagnostic and demographic characteristics.

Discussion and conclusions

Alcohol-dependent men with a primary diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder reported using more substance abuse treatment services than men with a primary diagnosis of alcoholism and no antisocial personality disorder. We found no difference between groups in whether they had ever sought substance abuse treatment. However, we did find that antisocial alcoholics attended treatment more frequently.

Our results do not support those of another study (3) that found that alcoholics with antisocial personality disorder were more likely to have received previous substance abuse treatment. However, in that study, subjects with antisocial personality disorder and those with high-severity symptoms of alcohol dependence were not categorized separately, which may have obscured the influence of antisocial personality disorder on service utilization.

Health services research on alcohol-dependent populations needs to consider the importance of psychiatric comorbidity and the age at onset of alcohol dependence. Our results are consistent with those of Dixon and colleagues (8), who found that patients with a combination of a substance-induced mood disorder and a substance use disorder were more likely to receive substance abuse treatment than patients with either diagnosis alone. An earlier age at onset of alcohol dependence has been associated with various subtypes of alcoholism, and these early-onset alcoholics often constitute a substantial proportion of patients who receive treatment services (10).

These preliminary results suggest that treatment demands and the cost of care for alcohol dependence are greater for patients with early-onset alcoholism and for those with substance-induced mental disorders. These results should be interpreted with caution, however, because of the limited sample size and the rigid inclusion criteria. More prospective studies of treatment outcome and service utilization are needed to elucidate these relationships further.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R29-AA-09735 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and by the Department of Veterans Affairs research service.

Dr. Murray is adjunct assistant professor, Dr. Anthenelli is associate professor, and Dr. Maxwell is adjunct assistant professor and statistician in the department of psychiatry at the College of Medicine of the University of Cincinnati. Dr. Anthenelli is also director of substance dependence programs at the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Send correspondence to Dr. Murray at the Psychiatry Service (116-A), Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 3200 Vince Street, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 (e-mail, [email protected]). Parts of this paper were presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism held June 20–25, 1998, in Hilton Head, South Carolina.

|

Table 1. Health services utilization by alcohol-dependent veterans with and without comorbid antisocial personality1

1. Zook CJ, Moore FD: High-cost users of medical care. New England Journal of Medicine 302:996-1002, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Humphreys K, Hamilton EG, Moos RH, et al: Policy-relevant program evaluation in a national substance abuse treatment system. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:373-385, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

3. Booth BM, Yates WR, Petty F, et al: Patient factors predicting early alcohol-related readmissions for alcoholics: role of alcoholism severity and psychiatric co-morbidity. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 52:37-43, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Siegel C, Alexander MJ, Lin S: Severe alcoholism in the mental health sector: II. effects of service utilization on readmission. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 45:510-516, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Helzer JE, Przybeck TR: The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 49:219-224, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Booth BM, Blow FC, Ludke RL, et al: Utilization of acute inpatient services for alcohol detoxification. Journal of Mental Health Administration 23:366-374, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hartz DT, Banys P, Hall SM: Repeat users of substance abuse services at a VA medical center. Psychiatric Services 46:285-287, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Dixon L, McNary S, Lehman A: One-year follow-up of secondary versus primary mental disorder in persons with comorbid substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1610-1612, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Cook CA, Booth BM, Blow FC, et al: Alcoholism treatment, severity of alcohol-related medical complications, and health services utilization. Journal of Mental Health Administration 19:31-40, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Anthenelli RM, Smith TL, Irwin MR, et al: A comparative study of criteria for subgrouping alcoholics: the primary/secondary diagnostic scheme versus variations of the type 1/type 2 criteria. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1468-1474, 1994Link, Google Scholar