Posttraumatic Stress Among Young Children After the Death of a Friend or Acquaintance in a Terrorist Bombing

Abstract

The effects of traumatic loss on children who reported a friend or acquaintance killed in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing of a federal office building were examined. Twenty-seven children who lost a friend or acquaintance and 27 demographically matched controls were assessed eight to ten months after the bombing. All but three of the children continued to experience posttraumatic stress symptoms. Those who lost a friend watched significantly more bombing-related television coverage than those without losses. Those who lost a friend had significantly more posttraumatic stress symptoms at the time of the assessment than those who lost an acquaintance. Parents and those working with children should be alert to the impact of loss even when it involves nonrelatives.

The 1995 Oklahoma City bombing of a federal office building killed 167 people. More than a third of respondents in an Oklahoma City middle and high school sample reported knowing someone killed in the blast (1). Bereaved youths watched more bombing-related television coverage and experienced more symptoms of posttraumatic stress than nonbereaved youths (2).

This pilot study examined bomb-related television exposure and posttraumatic stress in younger children who reported loss of friends or acquaintances in the bombing. We predicted that children with losses would watch more bombing-related television coverage and would have greater posttraumatic stress than those without losses.

Methods

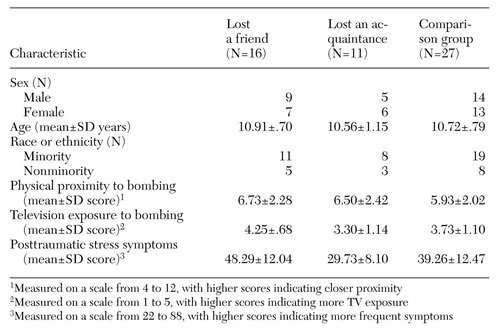

A convenience sample of 27 children in grades 3 to 5 who reported the death of a friend (N=16) or an acquaintance (N=11) in the bombing was drawn from a larger sample. No participants lost a relative. A control group of 27 children who reported knowing no one killed was selected from the same group of children and matched for sex, age, and racial or ethnic status. Table 1 summarizes characteristics of the sample and the comparison group.

Informed consent was obtained as required in the protocol approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center institutional review board. Children completed questionnaires in group settings eight to ten months after the bombing.

The questionnaire included items on physical, interpersonal, and television exposure to the incident and posttraumatic stress symptoms at the time of assessment. A composite physical proximity score measured hearing or feeling the blast, self-injury, and exposure to injured individuals.

The Impact of Event Scale—Revised (IES-R) (3), adapted from the Revised Impact of Event Scale (IES) (4), was used to measure posttraumatic stress symptoms. Possible scores for such symptoms ranged from 22 to 88, with higher scores indicating more and more frequent symptoms. The Revised IES (5,6,7) and the IES-R (1,2) have been used in other studies involving trauma in children. Participants rated the frequency of symptoms in the past seven days on a scale with four response options: not at all, rarely, sometimes, and often.

The independent variable had three levels derived from the participant's relationship to a deceased victim. These levels were operationally defined as knowing a deceased victim who was a friend, knowing a deceased victim who was an acquaintance, and not knowing any deceased victims. The amount of bomb-related television exposure and the mean score on posttraumatic stress symptoms as measured by the IES-R were the dependent variables.

One-way analyses of variance were used, and all multiple comparisons employed Aspin-Welch-Satterthwaite tests. The degrees of freedom varied by test due to incomplete questionnaires.

Results

As expected, no significant difference was found in the composite physical proximity score among the three groups (friend or acquaintance group and comparison group). Most children with losses reported that most or all of their television viewing in the days after the explosion was bomb related. As Table 1 shows, those who lost a friend watched significantly more bomb-related television coverage than those without losses (a mean of 4.25 versus 3.30; F=4.41, df=2, 51, p=.017; Aspin-Welch-Satterthwaite t=3.44, df=41, p=.001). However, those who lost a friend did not have significantly different scores from those who lost an acquaintance.

The mean score on posttraumatic stress symptoms for the group that lost a friend was significantly higher than the mean score for the group that lost an acquaintance (48.29 versus 29.73; F=7.72, df=2,37; p=.002; Aspin-Welch-Satterthwaite t=4.37, df=19.4, p<.001). However, neither loss group had significantly higher mean scores than the group that knew none of the victims (mean=39.26). Two children who experienced no losses scored two standard deviations above the mean on posttraumatic stress symptoms. Both children reported that all of their television viewing in the aftermath of the explosion was bomb related.

The score on posttraumatic stress symptoms correlated with the composite physical proximity score for the total sample (p=.018) and for the group that lost a friend (p=.019). It did not correlate with bomb-related television exposure in any of the groups.

Discussion

Children in this study reported bombing-related posttraumatic stress symptoms eight to ten months after the incident. Those who lost a friend reported significantly more symptoms than those who lost an acquaintance but not significantly more symptoms than those who knew no one killed. As the entire community focused on the incident, even children who knew no one personally involved may have felt part of the event. Only bomb-related programming aired on the major television stations for days after the explosion, and coverage remained extensive for many months. Children with personal losses may be more inclined than others to watch disaster television coverage and may be more troubled by it (2), but we suspect that those without losses watched as a way of participating in the event.

Our failure to find significant differences in symptoms of posttraumatic stress between those who lost a friend and those without losses may be due to the generally high levels of exposure to the bombing, through both physical proximity and media coverage, as well as through personal loss. Although we found no significant correlation between television exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms, other studies have linked disaster-related media exposure with such symptoms (1,2,8,9). As noted, two children without losses reported high rates of posttraumatic stress symptoms, and both reported that all of their television viewing in the aftermath of the explosion was bomb related, illustrating the role of the media in posttraumatic stress (1,2,8,9). Indeed, the scores of these two children more closely resembled those of the group reporting a loss than the scores of the no-loss group. The high scores of the two children may explain our failure to find significant differences in scores on posttraumatic stress symptoms between the group that lost friends and the group without losses. These children may also have been vulnerable due to any number of risk factors, such as prior exposure to trauma or emotional problems not assessed in the study.

This pilot study has a number of limitations. The sample size was small and may not be representative of the population of children in the greater Oklahoma City community. It is unclear to what extent a reported loss of a friend or acquaintance reflected loss of peers. Although 19 children were killed in the explosion, most were infants and preschool-aged children. Therefore, the children in this study probably did not lose age-mates. Furthermore, some may have reported loss when a parent knew someone killed and maybe even when they heard those around them talk of losses. Thus the children in the group that lost an acquaintance and those in the group that experienced no losses might differ little. On the other hand, it is likely that the children in this study experienced a sense of vulnerability associated with potential death at an early age because of the intense and enduring focus on child victims in this incident. Future studies should specifically examine the effects of loss of peers on posttraumatic stress in children.

Another limitation concerns the measure of television exposure, which was based on self-report without objective corroboration. Finally, due to the small sample size, the nonrandom selection of participants, and a relatively insensitive measure of loss, the real possibility of type II error exists; however, the use of matched comparison subjects to reduce variability does add confidence about the results.

Conclusions

This study underscores the need to assess the impact of trauma even when direct loss or overt symptoms are absent. Parents, school personnel, and others caring for or working with children should look for distress and be prepared to address it even when losses occur outside the family or in the general community. They should also monitor the television viewing of children and discuss potentially distressing content and images with them.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the Open Society Institute's Project on Death in America, the Children's Hospital Fund of the Children's Medical Research Institute, and the Commonwealth Fund.

Dr. Pfefferbaum is professor and chair of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, P.O. Box 26901, WP-3470, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73190-3048 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. McDonald is adjunct assistant of research and Dr. Leftwich is a postdoctoral fellow in clinical psychology at the Health Sciences Center. Dr. Gurwitch is associate professor and Ms. Messenbaugh is a psychology assistant in the department of pediatrics at the center. Dr. Sconzo is assistant superintendent for educational services with the Oklahoma City public schools. Ms. Schultz is a research assistant in the department of psychology at the University of Oklahoma.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 27 children who reported the death of a friend or an acquaintance in the Oklahoma City bombing and 27 children who did not know any of the victims (comparison group)

1. Pfefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Krug RS, et al: Clinical needs assessment of middle and high school students following the Oklahoma City bombing. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1069-1074, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Pfefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Tucker PM, et al: Posttraumatic stress responses in bereaved children following the Oklahoma City bombing. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1372-1379, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Weiss DS, Marmar CR: The Impact of Event Scale—Revised, in Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. Edited by Wilson JP, Keane TM. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

4. Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine 41:209-218, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Malmquist CP: Children who witness parental murder: posttraumatic aspects. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 25:320-325, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Sack WH, Clarke G, Him C, et al: A 6-year follow-up study of Cambodian refugee adolescents traumatized as children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32:431-437, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Yule W, Williams RM: Post-traumatic stress reactions in children. Journal of Traumatic Stress 3:279-295, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Breton J, Valla J, Lambert J: Industrial disaster and mental health of children and their parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32:438-445, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Nader KO, Pynoos RS, Fairbanks LA, et al: A preliminary study of PTSD and grief among the children of Kuwait following the Gulf crisis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 32:407-416, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar