Effects of Contracting and Local Markets on Costs of Public Mental Health Services in California

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the factors that determine whether mental health services provided under contracts with private providers are more cost-efficient than services provided directly by public mental health agencies. METHODS: Data on service costs for 1993 were obtained from the California Department of Mental Health cost reporting and data collection system and from a survey of local mental health departments. Ordinary least-squares regression was used to estimate the effect of contracting, local market conditions, and contracting procedures on unit costs of seven core mental health services: psychiatric inpatient care, rehabilitative day service, intensive day service, individual therapy, medication management, crisis intervention, and case management. RESULTS: Contracts with private providers significantly reduced costs for six core mental health services, but not for inpatient care. However, the extent of savings was affected by local market conditions, including the concentration of providers in an area, the provider organization's size, and the scope of services that the provider offered, as well as by contracting procedures—whether there was a formal contract review process and whether prices were negotiated with the majority of providers. CONCLUSIONS: The amount of cost savings that can be achieved from contracting with private providers is influenced by several factors, including competitive conditions in local markets. In some areas, direct provision of services by public mental health agencies may cost less. Contracting is a complex process that cannot be viewed as a panacea for improving cost-efficiency.

State mental health departments are implementing managed care and selecting entities to act as the central "managed care organization" for local service systems. In many states, such as California, county mental health authorities often act as public managed care organizations. A critical choice for these organizations is whether to produce services directly (public provision) or to purchase them in the market through contracts with private providers (private provision)—that is, to "make" or "buy" services.

Contracting with private providers is widely accepted as a low-cost substitute for public mental health services, yet there is little evidence about how contracting affects costs (1,2,3). Recent studies show that market structure affects health plan premiums (4,5), hospital structure (6,7), and health care contracts more generally (8). However, less attention has been paid to the effect of local market conditions on the cost of services when the purchaser is a public managed care organization, such as a county mental health authority.

Private provision can be less costly than public provision due to price competition among potential providers, incentives to innovate that could lower long-run costs, and avoidance of bureaucracy and regulations in employment contracts (9). For example, unlike most private providers, public employees are typically unionized. They have above-market wage rates and negotiated work rules that may reduce organizational flexibility and efficiency. Because of these factors, public managed care organizations would seem to achieve lower costs simply by buying services at market rates rather than by public provision (10). Thus no special attention to contracting procedures—the behavior and conditions associated with obtaining a contract—would seem to be warranted to achieve savings. We offer data that strongly suggest otherwise.

Theory and evidence suggest that market conditions and the action of contracting generate transaction costs that must be considered in the decision to make or buy services (11,12). Market conditions, notably the extent of competition, are important determinants of prices (13). Other research suggests that significant transaction costs may be related to searching for providers, negotiating contracts, and monitoring their performance, especially when coordination of services is important and when contract performance is hard to measure (9,12,14). The literature provides examples of states where the success of mental health contracting depends on service types and local market conditions (2,9).

California county mental health authorities have acted as managed care organizations since the 1991 "Program Realignment" legislation decentralized the responsibility for providing and financing mental health service from the California Department of Mental Health to county-based local mental health authorities (15). After the decentralization, Libby (10) identified wide variation in the level of contracting for services among the 59 California public managed care organizations and their local service systems and in the types of procedures employed in securing and monitoring these contracts.

Building on the work of Hu and associates (3), we analyzed unit-of-service costs for seven standard services as defined by state regulations, using individual service provider organizations as the units of analysis. This study provided empirical tests of how local market conditions and contracting procedures used by California public managed care organizations affect service costs of public and private providers.

Methods

Data sources and variables

The data on costs, contracting, and market structure came from three sources: the 1993 California Department of Mental Health cost reporting and data collection (CRDC) system; a survey conducted by Libby (10) of contracting procedures of public managed care organizations, the 59 local mental health authorities in California; and a 1993 survey by the U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics of county-level wages.

The CRDC system contains provider-level data from annual reports of expenditures and units of service provided. The reports are submitted for all county mental health providers, both contracted private providers and public providers. These expenditure data account for all funding sources, including county and state grants, Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance, and client fees. The data also include administrative costs (nonallocated) of public managed care organizations. The specific services analyzed are community psychiatric inpatient care (general hospital and other locally provided institutional care), rehabilitative day service, intensive day service, individual therapy, medication management, crisis intervention, and case management.

The effects of contracting on service costs were modeled at the provider level. A provider was defined as a service site consistent with reporting requirements of the CRDC; distinct satellite units of a parent agency were identified as separate providers. We maintained this distinction for two reasons. First, competition is spatially related such that firms that are geographically distributed within a county are more likely to compete with other providers. Second, some estimates indicate that mental health agencies with satellites provide services more efficiently than those without satellites (16). Failure to account for these effects may bias the estimated effects of local (county) market conditions. Unit costs for each service and provider were estimated by dividing total expenditures by total units of service reported. To allow pooling of all firms across the state in the unit cost analysis, we deflated the unit cost by an index of the average health worker's wage rate for each county in 1993.

Private providers were identified by a dummy variable, which was coded 1 if the provider was a private entity paid through a contract by a public managed care organization. The local market rate of contracting was estimated as total expenditures reported by contract providers relative to total publicly funded mental health treatment expenditures by a public managed care organization. The rate of contracting varied widely among California public managed care organizations, from zero to 100 percent, and averaged between 44 and 51 percent for the seven services studied here. In this study, between 17 and 59 percent of all providers associated with public managed care organizations, across the selected service types, were contract providers.

Based on Libby's survey (10) of managers of California public managed care organizations, two variables were developed as indicators of contracting procedures—contract review and direct negotiation. The first variable was coded 1 if the public managed care organization had a formal contract review process. The second was coded 1 if the public managed care organization was in a county where the level of price negotiation was high—that is, if more than 50 percent of mental health contracts were subject to direct negotiation on price by the public managed care organization. The negotiation variable and the contract variable interact so that the reported effect relates only to the unit costs of contracted firms.

Local market competitiveness for each type of service was measured using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) for each county. The HHI is calculated as the sum of the squares of all providers' individual market share for a given service type in each local market. Market share was calculated as the percentage of a local market's units of service for a given service type produced by each provider. For example, a provider with a local service monopoly would have a 100 percent market share yielding an HHI for that service of 10,000; a local market with five firms, each with 20 percent of the market, would yield an HHI equal to 202 × 5, or 2,000. Thus a higher HHI indicates less competition and should be positively related to market price.

The variable thus calculated was divided by 10,000 to yield a measure of local market competitiveness ranging from 0 to 1 for each service type and for each local public managed care organization's market. This market competition variable interacts with the contract variable to produce an effect that relates only to the unit costs of contracted firms.

Statistical analysis

Ordinary least-squares regression was used to model the effect of contracting and local market conditions on provider unit costs. The provider unit cost measures were log-transformed to correct for positively skewed distributions. The unit cost regression analyses controlled for firm-specific characteristics that may affect unit costs.

A variable scaled from 1 to 7 indicated the number of services among the seven studied that are offered by each individual provider. Another variable was a measure of provider size based on the ratio of a provider's service units to statewide mean units for providers of that service. A related variable was the provider size measure squared to account for nonlinearity in the relationship between size (a proxy for scale) and unit cost.

Results

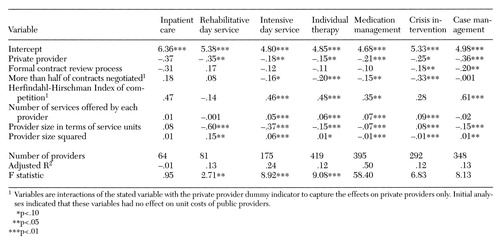

Table 1 shows results from the unit cost analysis for the seven service types. For six of the seven services, a significant inverse relationship was found between contracting and unit cost; the relationship for inpatient services was also inverse, but it was not significant. When market, provider characteristics, and contracting procedures were held constant, these estimates show that, on average, publicly funded mental health services provided by private providers through contracts were less costly than services provided directly by public providers.

These findings are generally consistent with the county-level estimates by Hu and associates (3), who found significant negative relationships between contracting and costs for four of the seven services measured at the county level—inpatient care, case management, medication management, and rehabilitative day care.

The variable based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, which indicates the effect of local market competition on contract providers' unit costs, was positively and significantly related to four of the seven service types: intensive day care, individual therapy, medication management, and case management. As expected, this finding indicates that when a provider's market share for any of the four service types was high, little competition existed among providers in that market and prices were higher. When contracts were written in such a market, unit costs were higher. For two additional services, crisis intervention and inpatient care, there was a positive but not a significant relationship between competition and price. Thus, although preliminary analysis indicated that private providers had lower unit costs, controlling for the effect of local market competition showed that having to write contracts in a noncompetitive environment may reduce the potential cost-efficiencies of contracting with private providers.

The variable that indicated a high level of contract negotiation on price had a negative and significant relationship with costs for intensive day service, individual therapy, medication management, and crisis intervention; the relationship with case management was also negative but not significant. The variable indicating the presence of a formal contract review was generally negatively related to costs, but it was significant only for case management and crisis intervention services. Thus the contracting procedures of public managed care organizations tended to reduce unit costs.

Highly significant scale effects were found in the regression analyses for all service types except inpatient care. The effects indicated an inverse relationship between the provider's size and unit cost, known as economies of scale. Four of the six services showed significant positive correlations between scope and unit cost: intensive day care, medication management, individual therapy, and crisis intervention. Thus offering more than one of the seven services significantly raised the unit costs of each service offered.

The production of multiple goods or services by a firm—its scope—is generally expected to reduce unit costs of each individual good or service, which is known as economies of scope. The counterintuitive results here may reflect the artificial delineation of individual markets for each service type. Providing more than one service may be correlated with a higher market share across all services and may thus be associated with higher prices.

Discussion

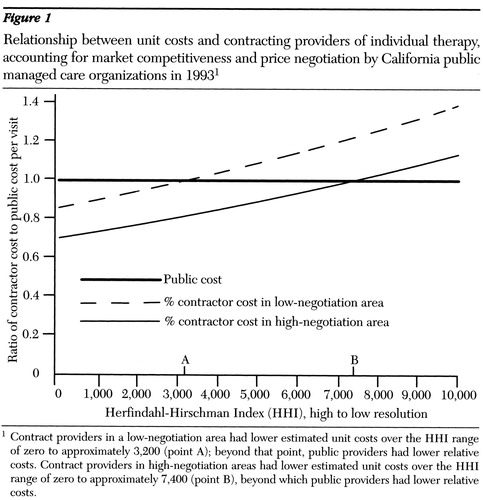

Figure 1 provides a stylized illustration of the relationship between unit costs and contracting for individual therapy, accounting for market competitiveness and price negotiation by public managed care organizations. The vertical axis plots estimated private provider unit costs as a percentage of public provider costs. The horizontal axis plots the Herfindahl-Hirschman index, indicating high to low competition over the range of zero to 10,000. A third variable, a shift factor for contractors' costs, is the extent of price negotiation attributed to the public managed care organization. Values reflect the average California mental health provider in the average county, with all other firm and market characteristics held constant.

Because public providers do not respond to market concentration and price negotiation levels, they are represented as a straight line at 1 on the vertical axis. The upper line shows the ratio of private contractors' costs to public providers' costs in areas where public managed care organizations negotiate fewer than half of their contracts, over a range of market competition described by the HHI. The lower slanting line indicates the same relative cost measure for contractors in areas with a high level of price negotiation.

Compared with public providers, private providers in areas with a low level of price negotiation had lower estimated unit costs over the HHI range of zero to approximately 3,200 (point A); beyond that point, public providers had lower relative costs. When public managed care organizations engaged in a high level of price negotiation with contract providers, the unit costs of these providers were lower over the entire range of local market conditions. Contract providers in areas with a high level of price negotiation had lower estimated unit costs over the HHI range of zero to approximately 7,400 (point B), beyond which public providers had lower relative costs.

To restate in terms of market structure, an HHI of approximately 3,300 could be associated with a market of three firms with equal market shares, while an HHI in the 7,400 range would require one provider to have at least an 85 percent market share. The 1993 mental health service data for California show that 40 public managed care organizations contracted for individual therapy services; 21 of these organizations had a low level of negotiation, and 19 had a high level. Of these, ten contract providers in low-negotiation areas and six in high-negotiation areas were located where local HHIs for the service they provide exceeded the thresholds under which private providers have lower costs than public providers.

We cannot draw direct conclusions about local price differences from this graph because other firm conditions will vary. It is clear, however, that many local markets in California are sufficiently concentrated—that is, they have low competition among providers for contracts—to question whether contracting will yield lower unit costs as a rule.

In another study, we examined two administrative cost models in which the public managed care organization was the unit of analysis (results of the regression analyses are available from the first author). Results support the notion, implied by transaction cost economics, that private contracting increases administrative costs for the public managed care organization, owing to the need to search for and monitor contract providers. The variables that reflect contracting procedures by public managed care organizations—formal review and a high level of negotiation—were significantly and positively related to dollars spent on contract administration for each contract provider in a county.

However, in that study there was a significant negative relationship between the extent of contracting and the total administrative expenditures by the public managed care organization for mental health services in the same reporting period. Thus, although contracting for services was found to generate significant governance costs per contractor for the public managed care organization, lower total administrative costs were associated with greater use of private contract providers.

In the study reported here, consistent with earlier studies, we found an inverse relationship between contracting and unit costs for all seven services, which was statistically significant for all but inpatient services. Services provided through private contractors were less costly than services provided directly by public providers. However, contracting alone was not sufficient to produce cost savings. Local market competition and the contracting procedures of public managed care organizations also affected unit costs; each was inversely related to lower unit costs and had independent effects. These two factors may generate compound saving if contracting procedures are used in certain competitive conditions.

Growth in public managed care and the use of contracted provider networks make private contracting increasingly prevalent. This growth has important implications for competitive bidding—a common contracting mechanism—as a conduit for market incentives, for both the procedures of the public managed care organizations involved and the local market context in which bidding occurs.

Conclusions

Although this study found support for the hypothesis that contracting for mental health services with private providers is less costly than direct public provision of services, resulting costs are affected by local market contexts. A threshold of local competition exists for each type of service, above which direct public provision of services may cost less. In addition, contracting procedures that enable a public managed care organization to take advantage of local competitive conditions affect this threshold and determine the extent of cost savings in a given market. The optimal level of contracting is difficult to assess for a specific local service system due to the interdependence of these factors. For example, developing a competitive array of contract providers, as local supply permits, also affects the scope and scale of provider firms, which in turn may increase or decrease local service and administrative costs.

Besides studying the mechanisms of writing and enforcing contracts for publicly funded mental health services, policy makers should pay attention to differences in outcomes of and access to programs operated by public and private providers, and across local systems with differing supplies of providers. Public and private providers may produce different qualities of services or select different mixes of clients to serve. Further, because services are not provided singularly but in multiple-service episodes, systems with many providers may have greater difficulty coordinating service episodes, particularly systems that have multiple treatment modalities and providers.

Compared with direct public provision of services, contracting may provide an opportunity to achieve savings by purchasing publicly funded mental health services. However, as this study suggests, contracting is a complex multidimensional process that cannot be viewed as a panacea for improving cost-efficiency.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by training grant 5-T32-MH18828 from the National Institute of Mental Health (Richard M. Scheffler, Ph.D., principal investigator) and NIMH grant P50-MH43694 to the Center for Mental Health Services Research in Berkeley, California (Lonnie R. Snowden, Ph.D., principal investigator). The authors thank Lonnie Snowden, Ph.D., Teh-wei Hu, Ph.D., and Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., for their helpful comments.

Dr. Libby is research director at the Center for Mental Health Services Research of the University of California, Berkeley, 2020 Milvia Street, Suite 405, Room 5610, Berkeley, California 94720-5610 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Wallace is a doctoral candidate in the health services and policy analysis program at the University of California, Berkeley. This paper is one of several in this issue on mental health services research conducted by new investigators.

Figure 1. Relationship between unit costs and contracting providers of individual therapy, accounting for market competitiveness and price negotiation by California public managed care organizations in 19931

1 Contract providers in a low-negotiation area had lower estimated unit costs over the HHI range of zero to approximately 3,200 (point A); beyond that point, public providers had lower relative costsContract providers in high-negotiation areas had lower estimated unit costs over the HHI range of zero to approximately 7,400 (point B), beyond which public providers had lower relative costs.

|

Table 1. Regression coefficients indicating the relationship between local market conditions and contracting practices of California public managed care organizations and providers' unit costs for seven types of services

1. Gardner LB, Scheffler RM: Privatization in health care: shifting the risk. Medical Care Review 45:215-253, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Schlesinger M, Dorwart RA, Pulice RT: Competitive bidding and states' purchase of services: the case of mental health care in Massachusetts. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 5:245-63, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hu T, Cuffel B, Masland M: The effect of contracting on the cost of public mental health services in California. Psychiatric Services 47:32-34, 1996Link, Google Scholar

4. Wholey D, Feldman R, Christianson J: The effect of market structure on HMO premiums. Journal of Health Economics 14:81-105, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Feldman R, Dowd B, Gifford G: The effect of HMOs on premiums in employment-based health plans. Health Services Research 27:779-812, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dranove D, White W: Price and concentration in hospital markets: the switch from patient-driven to payer-driven competition. Journal of Law and Economics 30:179-204, 1993Google Scholar

7. Melnick GA, Zwanzinger J, Pattison R: The effects of market structure and bargaining position on hospital price. Journal of Health Economics 11:217-233, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Robinson JC: Payment mechanisms, nonprice incentives, and organizational innovation in health care. Inquiry 30:328-333, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

9. Frank RG, Goldman HH: Financing care of the severely mentally ill: incentives, contracts, and public responsibility. Journal of Social Issues 45:131-144, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Libby AM: Contracting between public and private providers: a survey of mental health services in California. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:323-338, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Coase R: The nature of the firm. Economica 4:386-405, 1937Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Williamson OE: The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. New York, Free Press, 1985Google Scholar

13. Salinger M: The concentration-margins relationship reconsidered. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 22:287-335, 1990Google Scholar

14. Barzel Y: Measurement cost and economic organization. Journal of Law and Economics 25:27-48, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Masland MC: The political development of "Program Realignment": California's 1991 mental health care reform. Journal of Mental Health Administration 23:170-179, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Frank RG, Taube CA: Technical and allocative efficiency in production of outpatient mental health clinic services. Social Science and Medicine 24:843-850, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar