The Treated Prevalence of Bipolar Disorder in a Large Staff-Model HMO

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder was examined in a large staff-model health maintenance organization (HMO) in western Washington state. METHODS: Automated data for all 294,284 adults enrolled in the HMO or treated by HMO providers were used to determine the number of patients treated for bipolar disorder between July 1, 1995, and June 30, 1996. Patients with bipolar disorder were identified using computerized records of inpatient diagnoses, outpatient visit diagnoses, and outpatient prescriptions of mood stabilizers. Validity of the identification procedure was confirmed by review of a random sample of outpatient records. RESULTS: The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder in the HMO was .42 percent. Somewhat higher treated-prevalence rates were found for women, younger enrollees, family members of HMO subscribers, enrollees in some of the individual plans within the HMO, and enrollees in the state's Basic Health Plan program for low-income residents. Of the 1,236 adults treated for bipolar disorder, 93 percent made at least one visit to specialty mental health services, and 86 percent received mood-stabilizing medications. Only a small percentage of the 1,236 patients received treatment with an antidepressant, an antipsychotic, or a benzodiazepine without having a mood stabilizer prescribed. CONCLUSIONS: The treated-prevalence rate found in this HMO population is higher than rates previously reported for prepaid health plans and lower than estimates from large population surveys. The majority of treated patients received specialty mental health services and treatment with mood-stabilizing medications.

Bipolar affective disorder affects approximately 1 percent of the general population, with one-year prevalence rates from community-based studies ranging from 1.2 percent in the Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study (1) to 1.3 percent in the National Comorbidity Study (2). Studies of treated cases suggest much lower prevalence estimates (.5 percent), but such estimates may be low because they may miss untreated cases (3). Males and females are equally affected, and the mean age of onset is in the early 20s (4,5).

Bipolar disorder has been shown to cause substantial morbidity and mortality (6,7), and persons with the disorder are more likely to use health services of all types (8). The overall economic burden of the disorder has been estimated at $45 billion annually (9).

Although the number of individuals enrolling in managed care systems has been steadily climbing over the past two decades, little information exists about the epidemiology and treatment of patients in prepaid health plans with severe mental disorders such as bipolar disorder. Few plans have sufficient numbers of patients with severe mental disorders to develop specialized treatment programs for this population (10). One demonstration project in which patients with severe mental illness were enrolled in health maintenance organizations (HMOs) was terminated after nine months because the largest HMO withdrew from the study due to unexpectedly high treatment costs (11).

Some early evidence suggested that the proportion of patients treated for mental disorders is lower in prepaid practice settings than in the general population (12), and there is considerable debate as to whether prepaid health care systems are willing and able to enroll and treat patients with severe mental disorders such as bipolar disorder (13). More data on the prevalence and treatment of bipolar disorder within managed care systems are needed to answer these questions and to help these organizations develop a systematic approach to the care of patients with this disorder.

Research from Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region found that .16 percent of HMO enrollees received specialty mental health care for bipolar disorder during any given year (13). A recent study by Katzelnick (14) found that .28 percent of patients at a Midwestern HMO met criteria for a DSM-III-R diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

In this study, we examined the treated prevalence of bipolar-spectrum and bipolar disorder at the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, a large staff-model HMO in western Washington during a one-year period from July 1995 through June 1996. Our study had four objectives: to identify HMO patients who were being treated for bipolar affective disorder; to describe the treated prevalence of bipolar affective disorder at the HMO; to examine differences in treatment prevalence by age, gender, and type of insurance; and to describe the treatments used by patients treated for bipolar disorder.

Methods

Setting

The Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound (GHC) is a large staff-model HMO that provides comprehensive care on a capitated basis for approximately 400,000 persons in western Washington. Most members receive coverage through employer-subsidized plans. Approximately 10 percent of enrollees are covered by Medicare, and 7 percent are covered by Medicaid or by Washington's Basic Health Plan, a state program for low-income residents. The sociodemographic characteristics of the HMO enrollees reflect those of people living in the Seattle metropolitan area except that enrollees have a slightly higher level of education and fewer individuals are at the low and high extremes of income.

Primary care for adults is provided by approximately 360 primary care physicians, most of whom are board certified in family medicine. Outpatient specialty mental health services are available through physician referral or self-referral to six GHC mental health clinics staffed by approximately 20 psychiatrists and 90 nonphysician providers. Specialty mental health clinics emphasize short-term individual psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and group therapy. Typical coverage arrangements for outpatient care provide for unlimited psychiatric medication management visits (subject to copayments of $5 to $10 a visit) and ten to 20 outpatient psychotherapy visits (subject to copayments of $10 to $20 a visit). No referral or authorization is needed for specialty mental health care, and primary care physicians have no financial incentives to limit the use of mental health services.

Most inpatient and partial hospital psychiatric care is provided at facilities contracted to provide inpatient care at a fixed daily charge. Typical GHC coverage arrangements for inpatient care provide 14 to 30 days of treatment per calendar year, with coinsurance rates of 10 to 20 percent. Most enrollees have a prepaid drug benefit as part of their enrollment, and more than 95 percent of prescriptions filled by members, including those for antidepressant drugs, are filled at GHC pharmacies (15).

Sources of data

Data for this study were drawn from three separate automated databases maintained by the HMO. The databases are linked by each member's medical record number. They include an automated pharmacy system, which includes records of all prescriptions dispensed from GHC pharmacies; a database of diagnoses from all inpatient and outpatient visits; and a membership database that contains selected demographic information and information on members' insurance plans. We also collected diagnostic information from medical records in two primary care and two mental health clinics and from individual GHC staff psychiatrists.

Subjects

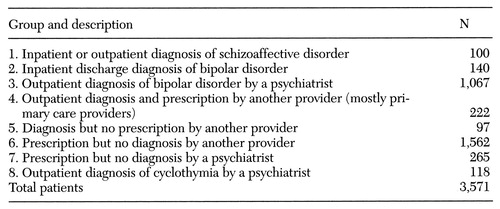

Potential subjects were all 294,284 persons who were receiving services from GHC providers or covered by GHC health plans between July 1, 1995, and June 30, 1996. Computerized records of inpatient diagnoses, outpatient visit diagnoses, and outpatient prescriptions for mood stabilizers (lithium, carbamazepine, and valproate) were used to identify all enrollees meeting any of the following criteria during the study period: any inpatient diagnosis of bipolar disorder (type I or type II), schizoaffective disorder, or cyclothymia; any outpatient diagnosis of bipolar disorder (type I or type II), schizoaffective disorder, or cyclothymia; any outpatient prescription for a mood stabilizer, excluding prescriptions from neurologists or prescriptions associated with a diagnosis of seizure disorder. As shown in Table 1, we organized the initial cohort of 3,571 patients into eight groups. These groups were hierarchically arranged so that if an individual met criteria for group 1, for example, he or she did not appear again in a lower group.

To examine the validity of this casefinding method, two psychiatrists (JU and GS) reviewed a random sample of 225 of the 3,571 outpatient medical records in two mental health and two primary care clinics. Specifically, we attempted to see if we could confirm the diagnosis of bipolar disorder using chart data or if there was some other indication for the use of a mood stabilizer such as the augmentation of antidepressant medication in unipolar depression. Through the use of structured chart abstraction forms and applying DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (16), subjects were classified as likely bipolar disorder, as having insufficient evidence for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, or as having a clear other indication for the use of a mood stabilizer.

We did not expect to confirm bipolar diagnoses in all cases. In some cases, the history of manic episodes was in the distant past, and we expected a moderate rate of insufficient evidence in the chart, especially for bipolar patients who were stable on their medication regimen.

Based on these chart reviews, we eliminated from the final sample all patients in groups 5 and 6 because it was ascertained in the validity check that more than 50 percent of patients in these categories did not appear to have bipolar disorder. Both of these groups had a large number of subjects for whom sufficient evidence of bipolar disorder was not documented in the chart or who were receiving mood stabilizers, particularly anticonvulsants, for indications other than bipolar disorder, such as for behavior problems in dementia or chronic pain syndromes.

The validity check showed that group 7 contained a large number of subjects for whom limited documentation of bipolar symptoms existed in the chart or who were receiving mood stabilizers for other indications, such as lithium used to augment antidepressant medications. We therefore used an additional strategy to clarify the diagnoses of the 265 subjects in this group. We asked all 15 GHC psychiatrists who had treated patients from this group to clarify whether these patients had bipolar disorder or if they had another diagnosis such as schizoaffective disorder, cyclothymia, or another mental disorder. Based on the diagnoses assigned by the psychiatrists, 33 patients from group 7 were reassigned to group 3.

We chose to accept all patients in groups 1 to 4 and group 8 for our final sample. In group 1, the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder was generally confirmed by chart review, and only one subject had other indications for the use of mood stabilizers. In groups 3 and 4, the diagnoses were generally confirmed by chart review, and no cases of other indications were found.

The resulting study sample included 1,680 subjects—1,462 patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, 118 patients with a diagnosis of cyclothymia, and 100 patients with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder.

Insurance status and treatments received

Information on insurance plans was obtained from the automated membership files of the HMO. Our analyses identified 155 individuals who were not enrolled in GHC but who received treatment for bipolar disorder at a GHC facility during the study period. These individuals paid for their treatment out of pocket and were not included in the prevalence calculations.

Information about treatments received were derived from the pharmacy database and the visit databases of the HMO.

Treated-prevalence rates and statistical analyses

Treated-prevalence rates were calculated by dividing the number of cases in each diagnostic category—bipolar-spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder types I and II, cyclothymia, and schizoaffective disorder—by the total number of persons in each category who were enrolled at GHC on January 1, 1996, the midpoint of our study period. The analyses of treated prevalence were restricted to enrollees age 18 and older, a total of 1,411 subjects.

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 7.1 for Windows. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the treated prevalence of patients in various subgroups.

Results

Sample characteristics

Our study sample of 1,411 subjects with bipolar-spectrum disorders included 932 women (66.1 percent) and 479 men (33.9 percent). The mean±SD age was 43.1±14 years. A total of 128 subjects (9.1 percent) were age 65 or older. We did not have information on the ethnicity, income, or employment status of these patients because the HMO does not maintain this information in a systematic way.

Treated prevalence

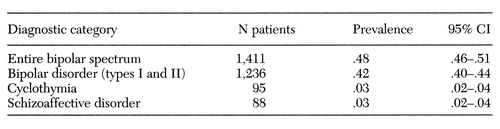

Table 2 shows the treated-prevalence rates of the bipolar-spectrum disorders among HMO members age 18 and older. The treated-prevalence rate for the entire bipolar spectrum, including bipolar disorder types I and II, cyclothymia, and schizoaffective disorder, was .48 percent. The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder was .42 percent. The treated prevalence of cyclothymia and schizoaffective disorder was .03 percent each.

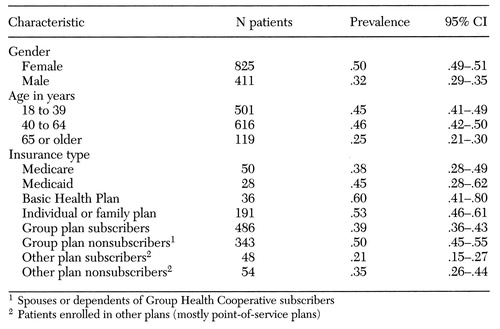

We then focused our analyses of treated prevalence on the diagnosis of bipolar disorder (N=1,236 patients) and examined the treated-prevalence rates by age group, gender, and insurance status. As Table 3 shows, the treated prevalence was lower among men than women (χ2=59.5, df=1, p<.01) and lower among adults age 65 or older than the other age groups (χ2=43.8, df=2, p<.01). The treated-prevalence rates varied significantly according to type of insurance plan within the HMO (χ2=56.9, df=7, p<.01). Nonsubscribers—individuals such as spouses and dependents who have GHC coverage but who are not the primary policyholder—had somewhat higher rates of treatment of bipolar disorder than subscribers.

Treatments received

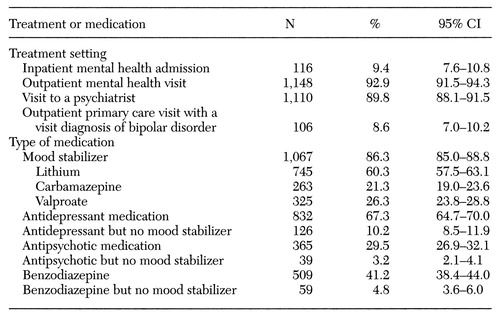

Table 4 shows the proportion of individuals treated for bipolar disorder who received specific types of services. These categories are not mutually exclusive, and individuals were classified as having received a service if they had at least one contact in a specific treatment setting during the one-year study period. Among the 1,236 adults with bipolar disorder, 9.4 percent had at least one inpatient psychiatric admission, 92.9 percent had at least one outpatient mental health visit, and 89.9 percent had at least one visit with a psychiatrist. Only 8.6 percent of patients in our sample received outpatient visit diagnoses of bipolar disorder from a primary care provider.

Table 4 also summarizes data on different psychotropic medications. Among the 1,236 patients with bipolar disorder, 86.3 percent received at least one prescription for a mood stabilizer during the study period. Less than 15 percent had a prescription for an antidepressant, an antipsychotic medication, or a benzodiazepine without having a prescription for a mood stabilizer during the study period.

Discussion

Limitations

Our research relied heavily on diagnoses entered into a database after each inpatient or outpatient visit rather than on diagnostic interviews. Thus the most significant limitation of this work concerns the validity of the casefinding method used. We reviewed the charts of 225 patients to confirm the validity of our casefinding method. In addition, we excluded 1,659 patients who received an outpatient visit diagnosis of bipolar disorder or a prescription for a mood stabilizer from a primary care provider because the validity check used for the casefinding method indicated that less than 50 percent of the patients in these groups appeared to have bipolar-spectrum disorders. This exclusion likely biased our sample toward patients treated in specialty mental health care, but to further clarify the diagnoses for these subjects would have required hundreds of chart reviews and diagnostic interviews with patients, and such efforts were beyond the scope and resources of this project.

However, we did include 222 patients (approximately 18 percent of our sample) who received both a diagnosis and a prescription from a primary care provider and who were thus treated exclusively in primary care. We asked GHC psychiatrists to identify the diagnosis for the 265 subjects who had received a prescription for a mood stabilizer but no visit diagnosis for bipolar disorder, and we retained in the final sample only those subjects who were given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder by their treating psychiatrist. We may have missed a small number of patients with bipolar disorder who were treated exclusively with other (second-line and third-line) mood stabilizers, such as clonazepam, verapamil, neuroleptics, and newer anticonvulsants, and a small number of patients who had concurrent diagnoses of bipolar disorder and seizure disorders (one of our exclusion criteria). All of these limitations introduced a conservative bias in our estimates of treated prevalence.

In addition to the exclusions mentioned above, it is likely that we missed a certain number of members who received treatment for bipolar disorder outside GHC as well as some patients who had bipolar disorder but did not receive a visit diagnosis or treatment for this disorder during the study period.

Treated-prevalence rates

At least .42 percent (N=1,236) of adult GHC members received treatment for bipolar disorder during a one-year period from July 1, 1995, to June 30, 1996. Because of the exclusions and limitations mentioned above, this figure is likely a conservative estimate of the actual treated prevalence.

Based on ECA data, Regier and colleagues (1) estimated an annual prevalence of bipolar disorder of 1.2 percent. Approximately 58.9 percent of subjects with bipolar disorder in the ECA study received professional services during the course of a year, translating into a treated-prevalence rate of roughly .7 percent. Our estimate of .42 percent is closer to rates found in other studies of treated samples (3) and higher than those reported from two other HMOs (13,14). In earlier research from Kaiser Permanente, Johnson and McFarland (13) found a treated-prevalence rate of bipolar disorder of .16 percent. Katzelnick (14) found that .28 percent of enrollees in a Midwestern HMO carried a DSM-III-R diagnosis of bipolar disorder. These figures are significantly lower than our rate of .42 percent, but the other authors used different casefinding methods relying primarily on diagnoses generated during visits to mental health providers.

It is not clear why HMO estimates of treated prevalence are lower than those from community psychiatric surveys such as the ECA study (1) and the National Comorbidity Study (2). It is possible that HMOs enroll and treat fewer patients with bipolar disorder. Our estimates may also be somewhat low because we did not include 1,659 patients who received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or a prescription for a mood stabilizer from a primary care provider. If between 25 and 50 percent of these individuals received treatment for bipolar disorder, our treated-prevalence rate would be between .6 and .75 percent, which is very close to the treated-prevalence rates reported in the ECA study.

It is also possible that the estimates from community surveys are somewhat higher than those from treated-prevalence studies because of a higher rate of false positive diagnoses made with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, which was administered by lay interviewers in those surveys. This possibility has been raised by Bebbington and Ramana (3).

Although population studies have found an equal prevalence of bipolar disorder among men and women (8), we found that women in our sample were significantly more likely to be treated for bipolar disorder than men. The equal prevalence found in population studies is in contrast to findings for unipolar depression; both population studies and treated prevalence studies have found an increased ratio of women to men (2,17,18).

Our findings suggest one of three possibilities. First, the true prevalence of bipolar disorder may be higher among women than men. Second, women with bipolar disorder may be more likely to enroll or to stay in HMOs such as GHC. Third, women may be more likely to use services for bipolar disorder than men. The last explanation would be consistent with research that has found women to be more likely to use specialty mental health services (19).

Our findings of a lower rate of treated bipolar disorder in the group aged 65 and older is consistent with the results of population-based studies that have found lower rates of bipolar disorder in older adults (8). We found that .25 percent of GHC enrollees age 65 and older were treated for bipolar disorder. Given the ECA lifetime prevalence estimates of .2 percent in subjects over age 65 (8,20), a relatively high proportion of patients with bipolar disorder in this age group may be receiving treatment at GHC.

Insurance coverage

Substantial variation was found in treated prevalence according to a member's insurance plan. Patients with the state-sponsored health plan for low-income residents and those covered under individual and family policies had the highest rates of treated bipolar disorder. Patients or policyholders with dependents who have bipolar disorder may have particular incentives to maintain health care coverage through the HMO. A study by McFarland and colleagues (21) of patients with bipolar disorder at Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region found that subjects with bipolar disorder had a longer tenure in the health plan than a control group of HMO patients without bipolar disorder. Because our study period was quite recent, we were not able to examine differences in length of enrollment between patients with bipolar disorder and other HMO patients, but the observation made by McFarland and colleagues would also be consistent with the possibility that patients with this disorder or their policyholders may be particularly motivated to retain current coverage with the HMO.

Interestingly, we did not find a higher rate of treated bipolar disorder among the group of enrollees with Medicaid or Medicare. The lower rate among Medicare enrollees is likely a reflection of the lower prevalence of bipolar disorder among older adults (8). The relatively modest treated-prevalence rate among patients with Medicare or Medicaid should be reassuring to HMOs that have been increasing their enrollment of Medicare and Medicaid patients over the past few years, although we cannot exclude the possibility that Medicare and Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder are less likely to enroll at GHC and are thus underrepresented in these estimates.

Treatments used

Of the 1,236 adult patients with bipolar disorder that we identified, 92.9 percent had at least one outpatient mental health visit during the study period, and 89.9 percent had at least one visit with a psychiatrist. This finding is similar to that from an HMO study by Johnson and McFarland (22) at Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region in which 84 percent of patients on lithium received services from a psychiatrist. In the ECA study (8), 38.5 percent of subjects with bipolar disorder received outpatient psychiatric treatment during a one-year period. At GHC, 9.4 percent of patients with this disorder received inpatient mental health treatment during the course of a year, a proportion somewhat higher than the estimate of 7 percent from the ECA study (20). Given the general decrease in inpatient hospitalization rates since the time of the ECA study in the early 1980s, the severity of the disorder in our treated prevalence sample may be somewhat greater than that in a population sample.

Narrow and colleagues (20) reported that 51.8 percent of all patients who were treated for bipolar disorder in the ECA study received outpatient specialty mental health care, and 55.9 percent received general medical care. In our sample, the majority of patients had a visit with a primary care provider, but only 8.6 percent of our patients received a visit diagnosis of bipolar disorder from a primary care provider.

Our findings on rates of specialty mental health care are biased by our exclusion of a large group of patients who received either a visit diagnosis or a prescription for a mood stabilizer from a primary care provider only. Because they did not use specialty mental health services, these individuals may have had less severe forms of the disorder.

Psychotropic medications

We found that 86.3 percent of the patients with bipolar disorder in our sample used a mood-stabilizing medication: 60.3 percent used lithium, 26.3 percent used valproate, and 21.3 percent used carbamazepine. These treatment rates may be higher than among patients who are exclusively treated in primary care, many of whom were excluded from our sample. However, the rates are quite similar to those recently reported by Katzelnick (14) from another HMO, where 62 percent of identified bipolar patients used lithium, 18 percent used valproate, and 13 percent used carbamazepine during a two-year study period. GHC patients had somewhat higher rates of prescriptions for valproate and carbamazepine. However, Katzelnick's study occurred during 1993 and 1994, two years before our study. At that time, divalproex sodium had not yet been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Of the 1,236 patients with bipolar disorder in our study, 67.3 percent used an antidepressant, 29.5 percent used an antipsychotic medication, and 41.2 percent used benzodiazepines. Only a small number of patients who received these medications did not also receive a prescription for a mood stabilizer during the course of a year. Prescription of an antidepressant without a concomitant prescription of a mood stabilizer is relatively contraindicated because of the risk of inducing a manic episode (23).

Although our finding of relatively high rates of use of mood stabilizers is encouraging, we cannot comment on the adequacy of these treatments in terms of dosage and duration. Previous work on the use of antidepressants among GHC patients documented a very high rate of treatment dropout after an initial antidepressant prescription (24), and it is quite likely that many of the subjects we identified in this study received only short periods of treatment or subtherapeutic doses of mood stabilizers. Data from a large Midwestern HMO showed that 46 percent of patients with bipolar disorder took mood-stabilizing medications for less than half of the two-year study period (14), and earlier research at Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region found that lithium users took the medication for only 34 percent of the study period (22).

Conclusions

The treated-prevalence rate for bipolar disorder found in this HMO is higher than rates previously reported for prepaid health plans and only somewhat lower than treated-prevalence rates from large population surveys. Our findings of relatively high rates of mental health service use and treatment with mood stabilizers are encouraging, but we cannot comment on the intensity and adequacy of these treatments. More research on the quality of care for patients with bipolar disorder is needed to help managed care organizations develop a systematic approach to their care.

Journal Seeks Short Items About Novel Programs

Psychiatric Services invites short contributions for Innovations, a new column to feature programs or activities that are novel or creative approaches to mental health problems. Submissions should be between 350 and 750 words. The name and address of a contact person who can provide further information for readers must be listed.

A maximum of three authors, including the contact person, can be listed. References, tables, and figures are not used. Any statements about program effectiveness must be accompanied by supporting data within the text.

Material to be considered for Innovations should be sent to the column editor, Francine Cournos, M.D., at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Drive, Unit 112, New York, New York 10032. Dr. Cournos is director of the institute's Washington Heights Community Service.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Abbott Laboratories. The authors acknowledge the suggestions of Joan Bagnall, M.D., M.P.H., Azmi Nabulsi, M.D., M.P.H., Jay Chmiel, Ph.D., and Kevin Noble, M.S.

When this work was done, Dr. Unützer, Dr. Simon, and Dr. Katon were affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Unützer is now affiliated with the Neuropsychiatric Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, 769 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, California, 90024 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Pabiniak, Ms. Bond, and Dr. Simon are with the Center for Health Studies of the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound in Seattle. This paper is one of several in this issue on mental health services research conducted by new investigators.

|

Table 1. Hierarchical groups used in casefinding of patients with bipolar-spectrum disorder among 294,284 enrollees of an HMO over a one-year period

|

Table 2. One-year treated-prevalence rates of bipolar-spectrum disorders among HMO enrollees age 18 and older

|

Table 3. One-year treated-prevalence rates of bipolar disorder among adult HMO enrollees, by gender, age, and insurance type

|

Table 4. Treatments and psychotropic medications used during a one-year period by 1,236 adults with bipolar disorder enrolled in an HMO

1. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bebbington P, Ramana R: The epidemiology of bipolar affective disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 30:279-292, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Tischler GL, et al: Affective disorders in five United States communities. Psychological Medicine 18:141-153, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al: Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 276:293-299, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Coryell W, Scheftner W, Keller M, et al: The enduring psychosocial consequences of mania and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:720-727, 1993Link, Google Scholar

7. Goodwin FK, Jamison K: Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

8. Weissman MM, Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, et al: Affective disorders, in Psychiatric Disorders in America. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

9. Wyatt RJ, Henter I: An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness:1991. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 30:213-219, 1995Google Scholar

10. Mechanic D: Sociological dimensions of illness behavior. Social Science and Medicine 41:1207-1216, 1996Google Scholar

11. Christianson JB, Lurie N, Finch M, et al: Use of community-based mental health programs by HMOs: evidence from a Medicaid demonstration. American Journal of Public Health 82:788-789,796-798, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kessler LG: Treated incidence of mental disorders in a prepaid group practice setting. American Journal of Public Health 74:152-154, 1992Google Scholar

13. Johnson RE, McFarland BH: Treated prevalence rates of severe mental illness among HMO members. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:919-924, 1992Google Scholar

14. Katzelnick DJ: Bipolar patients in an HMO. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. San Diego, May 17-22, 1997Google Scholar

15. Saunders K, Stergachis A, Von Korff M: Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, in Pharmacoepidemiology. Edited by Strom B. New York, Wiley, 1994Google Scholar

16. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

17. Simon GE, Von Korff M, Barlow W: Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:850-856, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Horwath E, Weissman MM: Epidemiology of depression and anxiety disorders, in Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Edited by Tsuang MT, Tohen M, Zahner GEP. New York, Wiley, 1995Google Scholar

19. Mechanic D: Integrating mental health into a general health care system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:893-897, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

20 Narrow WE, Regier DA, Rae DS, et al: Use of services: findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiological Catchment Area program. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:95-107, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. McFarland BH, Johnson RE, Hornbrook MC: Enrollment duration, service use, and cost of care for severely mentally ill members of a health maintenance organization. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:938-944, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Johnson RE, McFarland BH: Lithium use and discontinuation in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:993-1000, 1996Link, Google Scholar

23. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 151 (Dec suppl):1-36, 1994Google Scholar

24. Simon GE, Von Korff M, Wagner EH, et al: Patterns of antidepressant prescribing in community practice. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:399-408, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar