Abuse Histories of Psychiatric Inpatients: To Ask or Not to Ask?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The literature suggests that a high prevalence of a history of sexual and physical abuse among psychiatric inpatients is found when researchers inquire about abuse directly, but that relatively low rates are found in medical records. This study examined rates of reported abuse among patients who were and were not asked about abuse at admission. METHODS: The medical records of 100 consecutive admissions to an urban general hospital in New Zealand were examined after the introduction of a new admission form with a section inquiring about abuse. Use of the new admission form was recommended but not mandatory. RESULTS: The abuse section of the new form was completed for only 17 of the 53 patients with whom the new form was used. Review of the medical records of all 100 consecutive admissions revealed a prevalence rate of 32 percent for one or more of the four types of abuse. However, 14 of the 17 patients (82 percent) who were asked directly about abuse reported having experienced abuse. Nonsignificant trends suggested that male gender and being more disturbed or disturbing may be negatively related to the probability of being asked about abuse. Men may be particularly unlikely to disclose childhood abuse if not asked directly. CONCLUSIONS: The authors recommend including inquiry about abuse in standardized admission procedures and providing inpatient staff with training in how and when to ask patients about abuse and how to effectively follow up affirmative responses.

Prevalence rates for childhood abuse among psychiatric inpatients are significantly higher than among the general population (1). The prevalence of childhood sexual abuse among female inpatients ranges from 36 percent (2) to 85 percent (3). The 51 percent prevalence of childhood sexual abuse found in the two largest studies in the United States (4,5) was similar to the 52 percent prevalence found in a recent study in the United Kingdom (6) and the 49.8 percent prevalence in a recent review of 15 studies involving 817 subjects (1). The same review calculated that 43.5 percent of female inpatients had suffered childhood physical abuse and 64.1 percent had suffered either sexual or physical abuse as children.

Male inpatients report rates of childhood physical abuse similar to those of female inpatients (7). The rates for childhood sexual abuse among male inpatients are lower than for female inpatients, ranging from 24 to 39 percent (6,8,9), but are significantly higher than the rates for men in general (9,10).

However, in routine clinical practice, psychiatric patients disclose lower rates of abuse than they do in studies where they are asked directly whether they have experienced abuse. Jacobson and colleagues (11) found that only 12 percent of childhood abuse reported in response to direct questioning had been recorded in routine clinical assessments. Goodwin and associates (12) found an abuse prevalence rate of 50 percent among female inpatients who were asked directly about abuse; however, they found that in a control group of patients who were not asked about abuse, only 10 percent spontaneously reported abuse. Briere and Zaidi (13) reported that abuse was mentioned in the records of only 6 percent of a group of patients seen in a psychiatric emergency room but that abuse was reported by 70 percent of patients who were asked. Wurr and Partridge (6) found that while case notes suggested a 14 percent rate of childhood sexual abuse among adult inpatients, direct investigation produced a rate of 46 percent.

Many researchers have responded to such findings by recommending that a policy of regular, direct inquiry about abuse be introduced in all psychiatric settings, including inpatient units (1,7,8,14,15,16). Two assumptions underlie these recommendations. The first is that an accurate abuse history is crucially important for both diagnostic formulation (17) and treatment planning, allowing identification of individuals who could be offered appropriate treatment for the psychological sequelae of the abuse (1). The second assumption is that despite the high frequency of abuse among psychiatric patients, mental health professionals are still failing to ask patients whether they were abused as children. Wurr and Partridge (6) concluded as recently as 1996 that "a substantial number of patients on acute psychiatric wards have an unrecognized history of childhood sexual abuse."

Others, however, also assume that even patients who are asked about abuse are not always asked in the most productive way. One study in a setting where standard admission procedures included questions about abuse found that only 56 percent of patients who subsequently reported sexual abuse in a confidential questionnaire had disclosed the abuse when asked at admission (14). The researchers did not, however, report whether the questioning about abuse that was supposed to take place at admission actually occurred in all instances. They concluded that differences in disclosure rates could be explained by the confidential nature of the questionnaire and the questionnaire's inquiries about specific abuse behaviors, compared with the general questions about abuse assumed to have been asked at admission.

The study reported here addressed the following questions. First, does the inclusion on an admission form of a general question about abuse have any effect on disclosure rates? Second, does such an inclusion by itself—with no additional training for staff—ensure that inquiry about abuse occurs? Third, does a higher disclosure rate emerge among patients who were asked about abuse, compared with those who were not asked? Fourth and finally, is the probability of being asked about, or disclosing, abuse related to clinical or demographic variables?

Methods

The study was conducted at an acute psychiatric inpatient unit of a general hospital in an urban area of New Zealand. In October 1994 the unit began using a new admission form with 20 sections, one of which covered the patient's history of abuse. The section read, "Abuse history (includes physical, sexual, emotional, past and present. Please record negative findings or, if question not asked, include reasons why not)." The admission form previously used on the unit did not mention abuse.

The medical records of 100 consecutive patients admitted between January 1 and March 10, 1995, were reviewed in August 1995 by the first author. The purpose of the review was to locate reports of sexual or physical abuse that had occurred in childhood or in adulthood.

To check the reliability of the records reviews, 15 randomly selected records were reexamined by the first author without reference to data already gathered. One example of abuse that had been missed on the first review was found in the clinical notes section, used predominantly by nurses. All disclosures recorded in the study were confirmed during the blind reexamination.

Use of the new admission form was recommended but not mandatory, and the admitting psychiatrists did not use the form in all cases. Differences in disclosure rates could be measured according to whether the form had or had not been used. In addition, it was evident from many of the forms that the questions about abuse had not been asked, allowing a comparison in disclosure rates depending on whether the questions had or had not been asked.

We analyzed the relationship between patients' demographic characteristics, diagnoses, and measures of overall severity of psychopathology to determine whether they were related to the probability that the new admission form was used and, if it was used, the probability that the questions about abuse were asked. In instances where the abuse questions were not asked, we recorded how many of the other 19 sections on the admission form were left blank.

In this study, the operational definition of abuse was based on subjects' self-reports recorded in clinicians' written notes. Abuse was considered to have occurred if a subject reported abuse in response to inquiry on admission or if a subject's records included notes written by a mental health professional that identified abuse before or during the current admission.

Of the 100 subjects, 57 were men and 43 women. The mean±SD age was 37.6±11.3 years, with a range from 20 to 67 years. Sixty-eight were of European descent, 15 were Maori, 11 were Pacific Islanders, and six were classified as "other." Their primary diagnoses were schizophrenia for 34 subjects, major depressive disorder for 19, bipolar affective disorder for 17, substance use disorder for 16, schizoaffective disorder for ten, posttraumatic stress disorder for two, and eating disorder for two. Nine of the 16 subjects with a diagnosis of substance use disorder had comorbid schizophrenia (four subjects), major depressive disorder (three subjects), or bipolar affective disorder (two subjects).

Results

Use of the new form

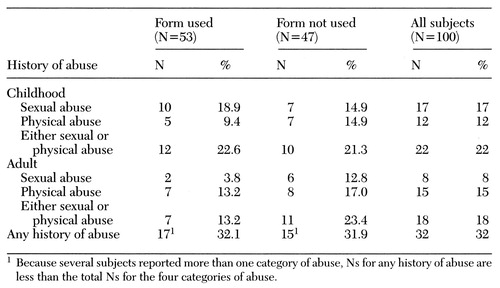

The new admission form was used in 53 of the 100 cases. Table 1 shows differences in rates of disclosure of abuse between cases for which the form was used and those for which the form was not used. None of the differences were statistically significant. When data for male and female subjects were analyzed separately, no significant differences emerged.

Asking about abuse

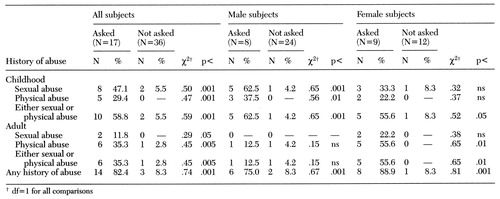

Among the 53 subjects for whom the new admission form was used, 17 were asked the questions about abuse. As Table 2 shows, significant differences in disclosure rates for all four abuse categories were found between those who were asked about abuse and those who were not asked. The difference was particularly large for the two categories of childhood abuse.

For men, the disclosure of childhood sexual or physical abuse was particularly related to being asked about abuse. Five of the eight men (62.5 percent) who were asked about abuse at admission reported that they had been sexually abused as children, compared with only one of the 24 men (4.2 percent) for whom the new form was used but the abuse questions not asked. The corresponding difference for the women (33 percent versus 8.3 percent) was not statistically significant. Similarly, childhood physical abuse was reported by three of the eight men (37.5 percent) asked about abuse and none of the 24 who were not asked; the corresponding difference for women (22 percent versus none) was not significant.

For women, the disclosure of physical abuse in adulthood was particularly related to being asked about abuse. Five of the nine women (55.6 percent) who were asked about abuse reported physical abuse as an adult compared to none of the 12 who were not asked.

Variables related to asking about abuse

Among subjects for whom the new admission form was used, neither age nor ethnicity were related to whether questions about abuse were asked. There was a statistically nonsignificant trend (p=.17) toward women being asked more often than men (42.9 percent versus 25 percent). Subjects with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were less likely to be asked than other inpatients (22.7 percent versus 38.7 percent), a nonsignificant trend (p=.22). Those who were involuntarily admitted were less likely to be asked about abuse than were voluntary admissions (23.3 percent versus 43.5 percent), a nonsignificant trend (p=.12). Subjects who spent time in the ward's intensive care unit were less likely to be asked about abuse compared with other inpatients (17.6 percent versus 38.9 percent), another nonsignificant trend (p=.12).

Avoidance of asking about abuse

In 36 cases the new admission form was used, but no information was recorded to indicate that questions about abuse had been asked. For 30 of those subjects, the section on abuse was left completely blank. For five subjects, admitting staff wrote "unknown" or "?" in the section. In one case, admitting staff recorded, in compliance with instructions on the form, that the subject was "not asked—too psychotic."

For two of the 36 subjects, the section on abuse was the only one of the form's 20 sections in which no information was recorded. These two subjects included the one considered "too psychotic" to respond, one who was not, however, considered too psychotic to respond to any of the other 19 sections. For eight of the 36 subjects, only one other section was left blank. For 25 of the 36 subjects, three or fewer other sections were left blank.

Although the raw data seem to indicate that the abuse section was being selectively avoided, statistical analysis of this hypothesis is problematic. If the analysis includes all 36 cases to determine whether the number of sections omitted differs from that expected by chance, all cells have expected frequencies of less than 5, thereby rendering the resulting (χ2 of 78 (p<.001) questionable.

Discussion

The rates of abuse found in this study—17 percent for childhood sexual abuse, 12 percent for childhood physical abuse, 22 percent for either sexual or physical abuse in childhood, and 32 percent for any abuse—are not inconsistent with studies, cited earlier, that have relied on medical records rather than on direct inquiry (6,11,12,13). Such studies, and the figures from the current study based on the records of all 100 subjects, can safely be assumed to be underestimating the prevalence of abuse.

Among subjects who were specifically asked about abuse, the prevalence rates—47.1 percent for childhood sexual abuse, 29.4 percent for childhood physical abuse, and 64.7 percent for either sexual or physical abuse in childhood—approximate the findings we cited earlier of research studies that relied on direct investigation.

Previous findings that routine clinical practice misses a large proportion of abuse histories are confirmed by the differences found in this study between the prevalence rate for all types of abuse when inquiry about abuse occurred on admission (82.3 percent), the rate based on review of all 100 subjects' records (32 percent), and the rate when inquiry about abuse did not take place at admission (8.3 percent).

However, a noteworthy finding is that having an explicit abuse section in an admission form seems, by itself, to have no impact on disclosure rates. This lack of effect can be explained by the fact that the questions about abuse often were not asked. In more than two-thirds of the cases where admitting psychiatrists did use the form, the abuse section was not filled out. A possible partial explanation for selective avoidance of the abuse section is that clinicians were using their judgment about the best time to ask sensitive questions and that many decided to wait until later in the subject's hospitalization. However, despite clear instructions to record on the admission form reasons for not asking about abuse, the instructions were followed in only one of the 36 cases where the section was not completed.

An accurate history of abuse has significant implications for clinical management. A referral for counseling or psychotherapy to address the long-term effects of the abuse cannot be considered if the abuse history is unknown. Given the recent findings of a strong statistical relationship between childhood abuse and psychosis in general (16,18,19,20,21) and the positive symptoms of schizophrenia in particular (17,19,20,22), knowledge of a patient's abuse history may assist in conceptualizing and contextualizing the patient's symptoms.

A reasonable conclusion to draw from this study is that inquiry about abuse does indeed need to be an integral component of history taking, as many have previously recommended. Addressing this issue may involve a decision to delay asking about abuse, for various reasons, but the reason for delay and a projected time for the inquiry should be clearly documented in the record. However, leaving decisions about whether to inquire about abuse at all to the clinical judgment of individual practitioners often appears to result in lack of inquiry and loss of clinical data that are crucially important to treatment planning.

Of additional importance is this study's suggestion that patients who are more disturbed and disturbing (as indicated by their use of the intensive care unit, involuntary admission, or a diagnosis of schizophrenia) may be even less likely to be asked about abuse than other inpatients. Clinicians should also note the nonsignificant trends that men are asked about abuse less often than women and that among men in particular, disclosure of childhood abuse may be dependent on their actually being asked.

Conclusions

The previous research cited here and the results we have reported suggest the following recommendations.

First, a standardized admission procedure that includes mandatory inquiry about abuse (with provisions for delay to a later point during hospitalization) appears worthy of consideration for inpatient units. It should not be assumed, however, that outpatient programs already have policies of routine abuse inquiry. Even community-based approaches that focus on the family may not deal adequately with child abuse (23).

Second, training of inpatient staff seems advisable if information about abuse is to be successfully gathered and acted on. Training may need to include an examination of the reasons staff may avoid inquiring about abuse, including the belief that highly disturbed or psychotic patients should not be asked because their responses may not be reliable. Clinicians should be informed that this belief is not supported by previous research (1), in which no relationship between psychosis and false allegations of abuse was found (24) and in which psychiatric patients tended to underreport rather then overreport abuse histories (14). Training may be particularly helpful if it fosters awareness of the groups of patients that are likely not to be asked about abuse—in this study, men and the more "disturbed"—and of those, such as men, for whom disclosure about child abuse is particularly dependent on being asked.

For some clinicians, avoidance of inquiry about abuse may be related to a belief that abuse is irrelevant in an inpatient setting. A review of the research demonstrating the relationship between childhood abuse and adult psychopathology in general, and the more severe types of disturbance frequently found in inpatient settings in particular (15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,25), might therefore be valuable.

Clinicians may also need training in how to inquire about abuse. Decisions about how and when to ask about abuse should be guided by findings that patients seem more willing to disclose abuse either in confidential self-report questionnaires (6,14) or after discharge (3). The possibility that some patients may think of disclosure in an inpatient setting as unsafe should be of concern to clinicians and managers. Clinicians may need training in how to explain to the patient, before asking about abuse, the possible outcomes of an affirmative response. Such explanations may help the patient feel safer.

Training should also cover the nature of the questions about abuse and whether they should be general or specific. Choice of questions requires careful planning in light of research indicating a more accurate disclosure rate with more specific questions (14). Care should be taken, as in all areas of inquiry, to avoid leading, suggestive, or repetitive questioning. Training should also clarify the specific and complementary roles of the various professions in assessing patients (26).

Clinicians may also need training in how to follow up affirmative responses to inquiries about abuse. Uncertainty about to how to respond to affirmative responses may contribute to reluctance to ask about abuse in the first place. The options for follow-up are probably best delineated at a unit policy level and should cover both treatment issues such as referral for abuse counseling and issues relating to reporting allegations of illegal actions to the authorities (27).

Dr. Read is senior lecturer in the psychology department at the University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Fraser is clinical coordinator of the Conolly unit at Auckland Hospital.

|

Table 1. Disclosure of a history of abuse by psychiatric inpatients for whom an admission form with specific questions about abuse was or was not used

|

Table 2. Disclosure of a history of abuse by psychiatric inpatients whose admission form had questions about abuse but who were or were not asked the questions about abuse

1. Read J: Child abuse and psychosis: a literature review and implications for professional practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 28:448-456, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Chu JA, Dill DL: Dissociative symptoms in relation to childhood physical and sexual abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:887-892, 1990Link, Google Scholar

3. Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, et al: Child sexual abuse and mental health in adult life. British Journal of Psychiatry 163:721-732, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Carlin AS, Ward NG: Subtypes of psychiatric inpatient women who have been sexually abused. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:392-397, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Craine LS, Henson CH, Colliver JA, et al: Prevalence of a history of sexual abuse among female psychiatric patients in a state hospital system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:300-304, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Wurr JC, Partridge IM: The prevalence of a history of childhood sexual abuse in an acute adult inpatient population. Child Abuse and Neglect 20:867-872, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Jacobson A, Richardson B: Assault experiences of 100 psychiatric inpatients: evidence of the need for routine inquiry. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:508-513, 1987Link, Google Scholar

8. Sansonnet-Hayden H, Haley G, Marriage K, et al: Sexual abuse and psychopathology in hospitalized adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 26:753-757, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Jacobson A, Herald C: The relevance of childhood sexual abuse to adult psychiatric inpatient care. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:154-158, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Palmer RL, Bramble D, Metcalfe M, et al: Childhood sexual experiences with adults: adult male psychiatric patients and general practice attendees. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:675-679, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Jacobson A, Koehler BS, Jones-Brown C: The failure of routine assessment to detect histories of assault experienced by psychiatric patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:386-389, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Goodwin J, Attias R, McCarty T, et al: Reporting by adult psychiatric patients of childhood sexual abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:1183 (ltr), 1988Link, Google Scholar

13. Briere J, Zaidi LY: Sexual abuse histories and sequelae in female psychiatric emergency room patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:1602-1606, 1989Link, Google Scholar

14. Dill DL, Chu JA, Grob M, et al: The reliability of abuse history reports: a comparison of two inquiry formats. Comprehensive Psychiatry 32:166-169, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Herman JL: Histories of violence in an outpatient population: an exploratory study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 56:137-141, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Swett C Jr, Surrey J, Cohen C: Sexual and physical abuse histories and psychiatric symptoms among male psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:632-636, 1990Link, Google Scholar

17. Ross CA, Anderson G, Clark P: Childhood abuse and the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:489-491, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Beck JC, van der Kolk BA: Reports of childhood incest and current behavior of chronically hospitalized psychotic women. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1474-1476, 1987Link, Google Scholar

19. Goff DC, Brotman AW, Kindlon D, et al: Self-reports of childhood abuse in chronically psychotic patients. Psychiatry Research 37:73-80, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Goff DC, Brotman AW, Kindlon D, et al: The delusion of possession in chronically psychotic patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179:567-571, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Lundberg-Love PK, Marmion S, Ford K, et al: The long-term consequences of childhood incestuous victimization upon adult women's psychological symptomatology. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 1:81-102, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Heins T, Gray A, Tennant M: Persisting hallucinations following childhood sexual abuse. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 24:561-565, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Allen R, Read J: Integrated mental health care: practitioners' perspectives. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 31:534-541, 1997Google Scholar

24. Darves-Bornoz J-M, Lemperlere T, Degiovanni A, et al: Sexual victimization in women with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 30:78-84, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Read J: Child abuse and severity of disturbance among adult psychiatric inpatients. Child Abuse and Neglect, in pressGoogle Scholar

26. Read J: The role of psychologists in the assessment of psychosis, in Practice Issues for Clinical and Applied Psychologists in New Zealand: A Handbook. Edited by Love H, Whittaker W. Wellington, New Zealand Psychological Society, in pressGoogle Scholar

27. Read J, Fraser A: Staff response to abuse histories of psychiatric inpatients. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 32:157-164, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar