The Clinical Characteristics of Possession Disorder Among 20 Chinese Patients in the Hebei Province of China

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This paper describes the clinical characteristics of 20 hospitalized psychiatric patients in the Hebei province of China who believed they were possessed. METHODS: A structured interview focused on clinical characteristics associated with possession phenomena was developed and administered to 20 patients at eight hospitals in the province. All patients had been given the Chinese diagnosis of yi-ping (hysteria) by Chinese physicians before being recruited for the study. RESULTS: The subjects' mean age was 37 years. Most were women from rural areas with little education. Major events reported to precede possession included interpersonal conflicts, subjectively meaningful circumstances, illness, and death of an individual or dreaming of a deceased individual. Possessing agents were thought to be spirits of deceased individuals, deities, animals, and devils. Twenty percent of subjects reported multiple possessions. The initial experience of possession typically came on acutely and often became a chronic relapsing illness. Almost all subjects manifested the two symptoms of loss of control over their actions and acting differently. They frequently showed loss of awareness of surroundings, loss of personal identity, inability to distinguish reality from fantasy, change in tone of voice, and loss of perceived sensitivity to pain. CONCLUSIONS: Preliminary findings indicate that the disorder is a syndrome with distinct clinical characteristics that adheres most closely to the DSM-IV diagnosis of dissociative trance disorder under the category of dissociative disorder not otherwise specified.

The experience of being "possessed" by another entity, such as a person, god, demon, animal, or inanimate object, holds different meanings in different cultures. Yet the phenomenon of possession states has been reported worldwide. In a survey of 488 societies in all parts of the world, Bourgignon (1) found that 437 of the societies (90 percent) had one or more institutionalized, culturally patterned form of altered states of consciousness. In 252 societies (52 percent), such experiences were attributed to possession.

Possession states are often accepted as normal. Affected individuals can even achieve status by being seen as having supernatural powers of healing and understanding. Alternatively, these experiences can be regarded as abnormal, particularly when possessed individuals become so distressed and dysfunctional that they seek assistance from healers and mental health professionals. Possession cases clearly regarded as abnormal present challenges of diagnosis and treatment. Little systematic research into this phenomenon has been done in psychiatry.

Issues surrounding possession are complicated by cross-cultural variation. How do members of different cultures differ and agree in their experience of and response to the phenomenon of possession? What is this phenomenon like in different cultural settings?

Researchers have explored these questions in basically two ways. The first way is to concentrate on the shaman—in many cultures the person who has specialized knowledge about altered states of consciousness and possesses special healing powers—exploring his rituals and the psychiatric implications of his behavior and experiences. The other approach, which has been adopted for this study, focuses on ordinary individuals who believe themselves to be possessed.

It is particularly important to examine persons whose experience of possession is dysphoric and disruptive to their social and occupational functioning. These individuals believe their experience is pathological and attribute their distress to supernatural causes, but they seek the help of physicians to alleviate their suffering. A physician who is unaware of the cultural contributions to the illness may overpathologize it, attributing a patient's belief in possession to psychosis. Alternatively, the patient could be diagnosed as suffering from a culture-bound illness. The danger of applying the culture-bound label is that illness may be misinterpreted as only a function of culture, when in fact these experiences, like most forms of psychopathology, usually result from a combination of factors.

The literature on possession in Chinese culture is limited. Most investigators have focused on the psychiatric status and rituals of the shaman (2,3). Yap (4) studied possessed individuals in Hong Kong, yet his hypotheses were couched in Western psychological theories, not Chinese terms. The research reported here represents an attempt to expand on the meager literature about possessed patients in Mainland China. We report findings of a pilot study that examined the phenomenology of possession disorder in the Hebei province of China.

Background

Chinese vernacular uses three terms to describe the possessed state: kwei-fu, dzao-mo, and zhong-xea (5). However, lay people may use the three terms interchangeably, without making the distinctions that would be made by a specialist in traditional Chinese medicine.

Kwei-fu suggests a state in which an external spirit of a deceased individual takes complete control over a person's identity. It is believed that on an individual's death, the soul leaves the body and becomes a free-floating spirit in the form of chi. The most notorious are the chi's of individuals who died of torture or from hanging. These chi's can invade the living body and cause possession. The following case, taken from the study sample, is an example of a woman who believed that she suffered from kwei-fu.

Case 1

The patient is a 30-year-old married woman, the mother of two children, from a rural peasant background. At the time of her presentation, she described a ten-year history of being possessed by the spirit of her dead aunt. She described the onset of her possession as occurring after her aunt's death: "My aunt and I had a good, close relationship since we were children. The night after she died, I felt I was possessed. I heard my aunt call me, and I answered her. Since then, I have been possessed." She described seeing the spirit of her aunt walk into her house as "a person in white, but without a head." The patient believed that her possession resulted in weight loss, a changed voice, and unusual behavior.

During "attacks," which would come on suddenly, she would believe that she was the spirit of her aunt. She would laugh and cry inappropriately and feel as if she had no control over her actions. She acknowledged being very sad and very scared during these episodes. She denied having difficulty concentrating, remembering, or attending to her surroundings. She also denied having difficulties in making the right judgments about day-to-day matters or being unable to distinguish reality from fantasy. However, she believed that while she was under the influence of the spirit, it would not be possible for someone to call her back to reality.

The patient claimed that before her experiences, she never believed in ghosts but that the possession caused her to believe in ghosts. She experienced four of these attacks, which she believed were precipitated by dreaming of her aunt or by hearing other people mention her aunt. Her family also believed she was possessed, and they maintained this belief despite the explanation of a doctor who gave the patient a diagnosis of hysteria.

The patient was treated by a variety of means, including traditional Chinese medicine, "shots," tranquilizers, and acupuncture. She believed her most effective treatment was the use of an exorcist. She did not believe that she suffered from a physical or mental illness but attributed all her symptoms to the possession.

In contrast to kwei-fu, dzao-mo suggests a state in which one's behavior and emotions are taken over by malevolent spirits. These spirits assume the form of fairies, whirlwinds, and snakes. It is generally believed that these malevolent spirits can take over one's life and interfere in the performance of good deeds.

In zhong-xea, the invading agents are attributed to a particular kind of chi—hsieh chi, or wayward chi, called ching. Ching is believed to be the essence of all inanimate and animate objects. The best known are the ching of snakes, foxes, and turtles. The following is a case, taken from the study sample, of a woman who suffered from zhong-xea, although she believed she had kwei-fu and dzao-mo.

Case 2

The patient is a 40-year-old peasant woman, the mother of five children, of Buddhist background, who resides in a rural area. She presented with complaints that "I feel anxious, and sometimes my brain is in a turmoil, as if there is some prickly sensation all over my body. Sometimes I feel a tingly sensation. I can't get to sleep at night because I seem to have seen something tiny and black before me. I am thus terrified. My family thinks I am sick and have brought me here."

The patient described her first attack as occurring at age 20, after a quarrel with her husband: "The first attack was at dusk when the day's work was almost over and when I was on my way to look for my husband. As it was getting dark, I felt something like a cat running across my feet. I was scared and quickened my steps. I saw my husband squatting ahead, but he didn't answer when I shouted. Later on, the catlike creature dashed right in front of me. I let out a cry, 'I'm scared,' and then lost my consciousness. I found myself in my house when I came to. Since then, I have suffered repeated attacks. My husband says that when I'm attacked I am possessed by different things, which I can hardly tell."

The patient initially claimed that she had no idea what was wrong with her, but later stated, "I heard that I was possessed by a turtle. I was quite confused… and began to talk nonsense. I don't know what I was talking about. Maybe something possessed me." She said that she was not sure what the possessing agent looked like, but knew that it made her tired. She stated that during the attacks, which came on suddenly, she had no control over her actions and that she acted differently, but was unaware of her behavior during the episodes.

She also acknowledged difficulty concentrating, remembering ordinary things, and maintaining attention. She was only partly aware of her surroundings and had difficulty distinguishing between reality and fantasy. While she was in the possessed state, no one could call her back to reality. She also acknowledged losing a sense of time and feeling very sad and very scared. She regains her "consciousness" as soon as "a doctor checks on me or gives me an acupuncture treatment."

The patient is not sure how many attacks she has had, but she claims they have occurred in each of the 20 years since the first one. She believes she is sick from spirit possession but not mentally ill. She described her disease as resulting from a "poor life, unhappiness, constant quarrels, irritation, and too much deliberation." Western-trained doctors have diagnosed her as suffering from hysteria, while traditional Chinese doctors described her case as "coma due to blocking of the respiratory system" or "an abnormal circulation of the blood of the liver." As treatment for her condition, she received "quietness or Chinese herb medicine." She believed that the most effective treatment was to "take Chinese herb medicine and Western medicine at the same time."

These two cases illustrate well the ways that complaints of possession are addressed in the People's Republic of China. Most of these patients are diagnosed as suffering from hysteria, yi-ping in the Chinese classification of mental diseases (6). Yi-ping is defined and treated as follows:

• Yi-ping (hysteria) is a common form of psychoneurosis with characteristics of suggestibility, exaggeration, emotionality, and egocentricity commonly related to adverse mental suggestions. It presents with sensory or motor impairment, organic and vegetative imbalance, and abnormal mental symptoms. Causation may be related to, modified by, or removed by suggestion.

• Symptoms may include movement disturbances (inhibition or hyperactivity), sensory disturbances (visual or auditory changes), emotional constriction or hyperemotionality, and psychological symptoms (wandering, amnesia, pseudodementia, or multiple personality).

• Course of disease includes an acute onset, limited and short duration, and possibility of recurrence after symptoms subside.

• Etiology is attributed to psychological factors; predispositional factors such as heredity, personality, suggestibility, and egocentric proneness to imagination; and physical factors.

• Treatment is aimed at removal of psychological conflict, stress, and adverse environmental influences with the cooperation and assistance of the family. Patients are instructed in how to cope with daily life and work problems and in the cultivation of self-discipline and how to overcome personality deficiencies. Symptomatic relief is offered to highly suggestible patients through suggestive treatments such as intravenous injection of glucose, electrical stimulation of affected body parts, verbal suggestion, massage, and exercises. Neuroleptic therapy is also used for relief of acute symptoms.

• Prognosis is usually good when intervention is timely.

Yi-ping remains a common diagnosis in China. It is used to explain a variety of presentations, only a minority of which are attributed by patients to possession. Although Western physicians have given up use of the term "hysteria," the Chinese still find it useful and are reluctant to modify the concept.

Methods

We adopted Crapanzano's definition of possession (7) because it was broad enough to encompass the Chinese view. Crapanzano defines possession as "any altered state of consciousness indigenously interpreted in terms of the influence of an alien spirit."

Subjects

Subjects were drawn from both the inpatient and outpatient settings of eight affiliated hospitals in Hebei province in the People's Republic of China. Twenty consecutive patients with the complaint of possession—kwei-fu, dzao-mo, or zhong-xea—were recruited. Patients with diagnoses of organic brain disorder, psychosis, or schizophrenia were excluded.

Data collection

We developed an interview protocol for the study using questions suggested by the literature on possession phenomena. (A copy of the instrument is available from the first author.) Five aspects of possession states were examined: demographic characteristics of subjects, the nature of presenting complaints (chief complaints), the circumstances leading to the possession experience, other symptoms associated with the chief complaints, and characteristics of the onset of the illness. The instrument was first developed in the English language, then translated into Mandarin (the Chinese national language) and written in the pin-yin (Beijing) characters used in the People's Republic of China.

All subjects were interviewed in 1982 by psychiatrists who were trained by one of the authors (QD) in the administration of the interview protocol to ensure uniformity of interview technique and data collection. Patients' verbatim description of chief complaints, circumstances surrounding the onset of complaints, and answers to specific questions were recorded. After the data were collected, patients' answers were translated back into English. The original Chinese version and the English-translated version were then compared to achieve uniformity of meaning. Ambiguity in the meaning of terms or words due to variations in local colloquial usage was resolved by consensus of the investigators.

Data analysis

Five aspects of the illness profile were analyzed: the demographic characteristics of the subjects, the nature of their chief complaint, the circumstances preceding the possession, the symptoms associated with the chief complaint, and whether the onset of the illness was acute or gradual. To preserve and to portray the indigenous cultural coloring as much as possible, patients' original descriptions of the chief complaints and precipitating events leading to onset of illness were tabulated for comparison.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The mean age of the possessed subjects was 37 years, with a range of 24 to 55 years. Subjects were predominantly female (85 percent), married (85 percent), and of peasant background (80 percent). Subjects had little or no education—50 percent had attended primary school, and 45 percent had no formal education. Twenty-five percent of the subjects had a religious affiliation, primarily Buddhism, and 75 percent had no religious affiliation. Ninety-five percent of subjects came from a rural area.

Chief complaints

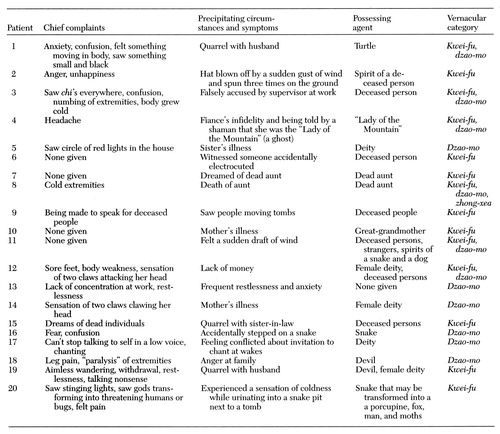

The chief complaints of subjects, listed in Table 1, were often highly dramatic and imaginative. Seven subjects (35 percent) had such complaints, including "seeing chi's everywhere," "seeing a circle of lights," and "being attacked by claws." Six (30 percent) had complaints of a somatic nature. Four (20 percent) gave no chief complaint.

Precipitating circumstances and symptoms

The major events or symptoms preceding the possession state and thought to be causative by the patients are presented in Table 1. Although more than one circumstance may have occurred before the onset of illness, the interview protocol asked for the one event or experience that the patient considered most important. Events included interpersonal conflict, such as a quarrel between the patient and her husband; occurrences that are subjectively meaningful only to the patient, such as a hat blowing off and spinning on the ground; death, including witnessing or hearing about a death or dreaming of a dead person; family illness; and economic problems.

Precipitating symptoms included emotional distress such as anxiety or anger and somatic symptoms such as headaches or insomnia. Six subjects (30 percent) described interpersonal conflict, five (25 percent) described subjectively meaningful events, three (15 percent) described family illness, three (15 percent) described a recent death or dreams of a dead person, two (10 percent) described emotional symptoms, and one (5 percent) had an economic complaint.

Associated symptoms

Possessed subjects often complained of a variety of associated symptoms. Accompanying symptoms included loss of control over one's actions (95 percent), behavior change or acting differently (for 90 percent of subjects), loss of awareness of surroundings (60 percent), loss of personal identity (55 percent), problems distinguishing reality from fantasy at the time of the possession (50 percent), change in tone of voice (50 percent), wandering attention (45 percent), misjudgment (45 percent), trouble concentrating (40 percent), loss of sense of time (35 percent), loss of memory (35 percent), loss of subjectively perceived sensitivity to pain (30 percent), and belief that one's body changed in appearance (20 percent).

Possessing agents

Table 1 shows patients' categorization of the agents responsible for their possession. Nine patients (45 percent) reported possession by deceased individuals, five (25 percent) by a deity, four (20 percent) by animal spirits, and two (10 percent) by a devil. One patient did not report a possessing agent. Five subjects (20 percent) reported possession by more than one agent. One subject believed that she was possessed by multiple deceased individuals; another believed that more than one type of spirit, such as a deity and a devil, was possessing her simultaneously.

Subjects were asked to categorize their possession experience using the Chinese vernacular terms regardless of whether it conformed strictly to the popular definitions of possession. In indigenous terms, five patients (25 percent) stated they had both kwei-fu and dzao-mo, eight (40 percent) believed they had kwei-fu, and six (30 percent) believed they had dzao-mo. One patient described having kwei-fu, dzao-mo, and zhong-xea.

Onset of illness

The subjects were asked to describe whether their symptoms developed suddenly or gradually over time. Eighteen (90 percent) of the possessed subjects reported an acute onset of illness.

Discussion

This study, which attempted to systematically delineate the phenomenon of possessed individuals in the Hebei province of China, has several limitations. The sample size was small, no control group was included, the interview instrument was not standardized, and the diagnosis was based on Chinese diagnostic criteria. Nonetheless, several interesting clinical findings were revealed. The study also raises methodological issues involved in cross-cultural clinical research.

The possession phenomenon has been found predominantly to affect women of lower educational background across cultural groups, worldwide (1). Our preliminary data appeared to reinforce these findings.

The findings raise questions about the role of susceptibility to folk beliefs in suggestible individuals who lack education. They also raise the question of whether the possession experience is a socially sanctioned mechanism that allows individuals in an oppressed social role to act out intolerable sociopsychological conflict (1). Many studies of possession report data obtained from sociological and anthropological field work. However, information on subjects' intrapsychic state is often missing. Our findings suggest that clinical information is as important as sociological and anthropological data for gaining a comprehensive understanding of the possession phenomenon.

The explanatory model of possession among Chinese encompasses a rich folklore. In addition to possession by spirits and deities, which has been reported among Western cases, possessing agents among Chinese can include animals, such as foxes and turtles, and inanimate and symbolic objects. This pattern is consistent with folk beliefs in other parts of Asia (8). Our study shows the importance of understanding possession in the context of culture, as should be true for the understanding of all psychiatric phenomena.

We examined how the clinical profile of possession among Chinese in Hebei, China, compares with the diagnostic criteria recommended in DSM-IV (9) and ICD-10 (10). DSM-IV places pathologic possession in the category of possession trance under the diagnosis of dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. ICD-10 also has a category of trance and possession disorder. DSM-IV defines dissociative trance disorder as single or episodic disturbances in the state of consciousness characterized by the replacement of the customary sense of personal identity by a new identity (9). This change is attributed to the influence of a spirit, power, deity, or other person, and is associated with stereotyped involuntary' movements or amnesia. The dissociative or possession trance is not a normal part of a broadly accepted collective cultural or religious practice.

DSM-IV reminds us that dissociative symptoms are also found in acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and somatization disorder. Moreover, belief in "possession" might also be part of a delusion associated with a thought disorder. Patients in cultures that endorse possession as a plausible cause for pathology might assume when experiencing any number of general medical or psychiatric illnesses that they have been possessed.

Our study did not address key diagnostic issues that differentiate possession disorder from other DSM-IV disorders among Chinese and members of other cultures; to do so would require the presence of control groups. However, it is essential for clinicians to screen for other general medical and psychiatric illnesses when they encounter patients who believe they are possessed.

The conditions of the 20 patients in our sample seem to fit the category of dissociative trance disorder. This apparent match may be due to the patients' first being diagnosed with yi-ping, or hysteria, before entering the study. Highly suggestible individuals are most vulnerable to developing hysteria, as well as dissociation (11). If a general belief in possession is combined with a propensity to dissociate, the likelihood of developing any dissociative disorder attributed to possession is increased. Although the symptoms these patients reported were largely dissociative, we cannot assume that all cases of possession would fit a diagnosis of dissociative trance disorder.

Possession disorder is basically an illness of attribution that has intrinsic meaning to the individuals suffering from it. Illnesses of attribution are defined not so much by their signs and symptoms as by their presumed etiologic mechanisms. Like other illnesses of attribution—including susto, a Latin American folk illness attributed to fright, and hwa-byung, a Korean syndrome attributed to the suppression of anger (12)—the possession experience is attributed to the invasion of the living body by an alien spirit. The clinical manifestations of possession gain meaning that stems from this central belief.

The methodological approach taken in this study was to examine the phenomenon of possession using data and diagnostic criteria from the perspective of the subjects' cultural background, rather than exclusively relying on Western cultural understanding. We believe there is merit to this approach. By examining the diagnostic criteria from the perspective of the patients' cultural background, we avoided committing the "category fallacy" of obtaining biased clinical data based on study approaches that stem purely from a Western cultural perspective (13,14). Although DSM-IV was not available at the time of our study, our findings on the characteristics associated with the experience of possession in our study sample match quite well the DSM-IV criteria for dissociative trance disorder.

Conclusions

When a clinician encounters a patient who believes that he or she has been possessed, two issues should be kept in mind. First, possession is a culturally influenced explanation for illness. It is best understood as a syndrome for which any medical or psychiatric illness could be responsible and should be considered. Second, the belief in possession, combined with dissociative symptoms, may suggest, in particular, the phenomenon of dissociative trance disorder. Besides screening for common medical and psychiatric conditions, the clinician should examine the particular cultural context in which the patient presents.

Acknowledgments

For assistance with data collection, the authors thank Shi Shu-min, M.D., Wan Xiu-lan, M.D., Chen Zhi-an, M.D., Wan Gui-zhi, M.D., Zhang Ton-yan, M.D., Ni Hong-gun, M.D., Liang Zhong-hou, M.D., Don Jin-sheng, M.D., Jin Shu-guo, M.D., Yin Jin-dong, M.D., and Han Min, M.D.

Dr. Gaw is associate professor in the division of psychiatry at the Boston University School of Medicine and lecturer on psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Ding is associate professor in the department of neuropsychiatry at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Hebei Medical College in Shijiazhuang, Hebei, People's Republic of China. Dr. Levine is associate professor of clinical psychiatry in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. Ms. Gaw is a psychotherapist in Lexington, Massachusetts. Address correspondence to Dr. Gaw at the Department of Psychiatry, Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Medical Center, 200 Springs Road, Bedford, Massachusetts 01730.

|

Table 1. Chief complaints of 20 hospitalized psychiatric patients in the Hebei province of China who believed they were possessed, the circumstances and symptoms they believed caused their possession, their identification of the possessing agent, and the possession state according to Chinese vernacular categories

1. Bourgignon E: Religion, Altered States of Consciousness, and Social Change. Columbus, Ohio State University Press, 1973Google Scholar

2. Potter J: Cantonese shamanism, in Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society. Edited by Wolf A. Stanford, Calif, Stanford University Press, 1974Google Scholar

3. Tseng WS: Psychiatric study of shamanism in Taiwan. Archives of General Psychiatry 26:561-565, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Yap PM: The possession syndrome: a comparison of Hong Kong and French findings. Journal of Mental Science 106:114-137, 1960Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Ding Q, Wang K, Kuo YR: Possession Phenomenon From the Perspective of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Shijiazhuang, Hebei Medical College, 1997Google Scholar

6. Zhang W: Hysteria, 2nd ed. Beijing, People's Health Publishing House, 1988Google Scholar

7. Crapanzano V, Garrison V (eds): Case Studies in Spirit Possession. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

8. Eguchi E: Between folk concepts of illness and psychiatric diagnosis: kitsune-tsuki (fox possession) in a mountain village of Western Japan. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 15:421-451, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

10. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 1992Google Scholar

11. Janet P: A symposium on the suDZonscious. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2:58-67, 1907Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Kim LI: Psychiatric care of Korean Americans, in Culture, Ethnicity, and Mental Illness. Edited by Gaw AC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992Google Scholar

13. Kleinman A, Kleinman J: Somatization: the interconnections among culture, depression experiences, and the meaning of pain, in Culture and Depression. Edited by Kleinman A, Good B. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1986Google Scholar

14. Lewis-Fernandez R: The proposed DSM-IV trance and possession disorder category: potential benefits and risks. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review 29(4):301-317, 1992Google Scholar