Psychiatric Emergency Service Use After Implementation of Managed Care in a Public Mental Health System

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined whether implementation of managed care in a public mental health system affected return visits to psychiatric emergency services within 180 days of an index visit. METHODS: Data were taken from an administrative database of 75,815 patient visits made to a hospital-based psychiatric emergency service for mental health care between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2002. Rates of return visits for patients whose index visit occurred at least 26 weeks before a system of managed care was implemented in 1999 were compared with rates for patients whose index visit occurred after the implementation but at least 26 weeks before the data collection period ended. Declining-effects modeling was used to adjust for patients' gender, ethnicity, age, and admission status. RESULTS: A total of 37,371 patients met study criteria for inclusion: 21,135 before managed care was implemented and 16,236 after managed care was implemented. In the pre-managed care group, 3,687 patients (17 percent) made a repeat visit within 26 weeks of their index visit; 2,369 patients (15 percent) in the post-managed care group made such a repeat visit. For any given index visit to the psychiatric emergency department, patients who presented for treatment after managed care were only 90 percent as likely as patients who presented before managed care to have a return visit within the first five weeks after the index visit. However, there was essentially no difference between groups in the likelihood of a return visit by week 26 after the index visit, suggesting that managed care delayed, but did not eliminate, return visits. In addition, the number of police-accompanied index visits continued to rise after managed care was implemented (from 32.0 to 52.6 percent of all index visits), suggesting that increasing numbers of patients with mental illness in need of treatment were coming to the attention of law enforcement officials after managed care was implemented. CONCLUSIONS: Managed care strategies are often used to reduce reliance on emergency services. In this study, managed care delayed, rather than prevented, return visits to the psychiatric emergency service.

By 2003 public mental health services were being administered under some system of managed care in 27 states (1), and this structure was under consideration in another 21 states. Although the consumer's experience in seeking and receiving treatment is assumed to have changed under these rapidly emerging new structures (2), assessing clinical outcomes continues to be a challenge (3,4,5,6). Since deinstitutionalization the use of psychiatric emergency services has been studied as one way of assessing outcome in community-based systems of care (7,8,9,10). As in the past, examination of emergency service revisit patterns may provide information about the equity of, and access to, care provided under evolving managed behavioral health treatment systems.

Even though psychiatric emergency services were originally conceptualized as an essential resource for persons with mental illness who reside in the community (11), frequent and repeated use of such services in lieu of alternative care has historically been viewed as undesirable (12,13,14). For example, a "bounceback" visit to the emergency department—that is, a visit occurring within days of inpatient discharge—is generally viewed as an indicator of inpatient treatment failure (15). If stringent limits placed on inpatient care result in the premature discharge of large numbers of marginally stabilized patients, an increase may be observed in the frequency of "bounceback" visits to the psychiatric emergency service (16).

In addition, characterization of "revolving door" patients—that is, frequent users of psychiatric emergency services—has historically helped identify groups of consumers whose needs are not adequately met by outpatient systems of care (16,17,18,19). Some fear that diminished treatment dollars associated with managed care structures result in decreased availability of intensive, community-based services for persons who are the sickest and most vulnerable (20,21,22). If true, because the psychiatric emergency service is the most accessible point of care in the public mental health system, emergency service rosters should reflect increased numbers of repeat visits by patients with severe and persistent mental illness.

Finally, reduction in resources after implementation of managed care systems is thought not only to leave vulnerable patients without adequate care but also to promote increasing "transinstitutionalization," defined as the de facto management of mentally ill patients in the criminal justice system (23,24,25). If this concern is valid, an increase in both initial and repeat visits to the psychiatric emergency service during which the patient is accompanied by the police might be observable under managed care structures.

The introduction of a regional system of managed mental health care in our public mental health catchment area in 1999 provided the opportunity for a natural experiment to test these assumptions. This study compared the rate of return visits to the psychiatric emergency service for patients presenting before and after adoption of the new system.

In July 1999 the phase-in of a system of behavioral managed health care, called NorthSTAR, was begun in seven north Texas counties, including Dallas County where the study hospital (Parkland Hospital) is located. NorthSTAR is described by its architects as a blended-funding, integrated, behavioral health carve-out that eliminates the separation of treatment silos for substance abuse and mental health treatment. By December 1999 it functioned both as a full-risk, capitated, per-member, per-month 1915b Medicaid waiver program and a flat-fee reimbursement program for the medically indigent. These functions are rolled into a private sector-operated open system of care in which consumers are given a choice of providers (26). About 30 percent of the funding and patient base for the program came from Medicaid.

At implementation, the NorthSTAR region ranked 35th out of 40 in Texas for mental health expenditures, and Texas ranked 42nd out of 50 states in per capita expenditures for mental health (27). Despite the underresourced system into which it was introduced, NorthSTAR had as a primary goal improved access for all covered patients—for example, it sought to eliminate long wait times before treatment enrollment.

NorthSTAR divided local functions into organizations designated as treatment "providers" and one "authority" appointed to oversee how care was being provided. Existing care structures were absorbed into new provider networks, and a handful of new providers emerged. Pre- and post-managed care systems used essentially the same menu of services, including medication and case management; psychotherapy; assertive community treatment for individuals with severe illness, a history of multiple hospitalizations, or both; and supported housing and employment. However, the number of consumers who received assertive community treatment services increased from 79 to 450 in the first 18 months after NorthSTAR was implemented.

According to NorthSTAR creators, between July 1999 and December 2002 the major change in provision of care associated with NorthSTAR implementation was more of a "culture shift"—a change in approach to care delivery—than a change in the quantity or type of care. The new system included prospective and concurrent clinical review and fixed rates of reimbursement, but eligible "priority populations" remained unchanged. These included patients in crisis with a Global Assessment of Functioning score of 50 or less; a primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia was necessary to obtain ongoing services. The total population of consumers served increased from 6,000 to 8,000 per month in 1998 to more than 13,000 per month in 2001 (28), while the wait for outpatient service dropped from weeks to a mandated maximum of 96 hours after initial telephone contact.

No change in policies regarding the use of mental health emergency services was apparent during the implementation of NorthSTAR, and examination of hospitalization and aftercare plans in the first 42 months under the new system revealed no major shifts in aftercare referral patterns for the psychiatric emergency service. In March 2001 (20 months after managed care implementation) NorthSTAR designated three local "front door" crisis sites that provided 23-hour observation before hospital admission. After this change potential inpatients from the study hospital's psychiatric emergency department were diverted to these sites before or instead of inpatient admission. For the nine months after this change, the study hospital's psychiatric emergency census increased by an average of 33 patient visits per month.

By using a hospital-based database of all patient visits made to Parkland Hospital's psychiatric emergency service between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2002, this descriptive study examined bounceback and revolving-door visits as well as visits initiated by the police. We sought to determine the frequency of each type of visit before and after NorthSTAR was implemented. In addition, we attempted to characterize subgroups of patients in the psychiatric emergency service who appeared to adapt less readily to the new system of care.

Methods

Parkland Hospital's psychiatric emergency service averaged 800 to 900 patient visits per month throughout the study period and served as one gateway into mental health services in the public sector. Other than changes in procedures related to the structure of public mental health care, there were no detectable major changes in mental health care policy, population distribution, substance abuse patterns, or legal policies for offenders with mental illness in Dallas County during the study period. Patterns of psychiatric emergency department visits were therefore assumed to be one reasonably sensitive indicator of the impact of NorthSTAR on help-seeking behavior among persons with mental illness receiving care in the public sector. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Data source and major study variables

The administrative database from which emergency service information was extracted for these analyses was created by medical record review and included both demographic characteristics (age, gender, and ethnicity) and information about the visit—for example, whether the visit was voluntary or whether the patient had ever been seen in the hospital system before the index visit.

To study NorthSTAR's impact on psychiatric emergency service revisit rates, two patient cohorts were established within the database. The pre-managed care cohort included patient visits between January 1, 1995, and June 30, 1999; the post-managed care cohort included patient visits between July 1, 1999, and December 31, 2002. For this study we assumed that a return visit within 26 weeks of the index visit constituted a repeat visit within the same illness episode and was thus related to the nature of the treatment received after the index emergency visit. In contrast, any visit by the same patient more than 26 weeks after an index visit was regarded as a second index visit—that is, we assumed that this second index visit was associated with a new episode of illness. Therefore, the same patient could have more than one index visit during each study period.

The study sought to characterize patients' help-seeking patterns during any given illness episode before and after managed care was implemented. We stopped identifying new index visits 26 weeks before the end of each data enrollment period. To avoid overpopulating the post-managed care group with patients who had a previous use history, the post-managed care working sample included patients who reentered the emergency department on or after July 1, 1999, with no psychiatric emergency service use for the previous 26 weeks.

A declining-effects model (293031, unpublished manuscript, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Crismon ML, 2004) was adapted to measure the impact of managed care on return visit rates. This strategy enabled us to test for the ability of the managed care system to reduce repeat psychiatric emergency visits within one week of the emergency index visit. This model also includes a measurement of growth that was used here to examine whether the initial effect of managed care on emergency revisit rates increased, remained constant, or decreased as time passed over the 26 weeks after the index visit. Unlike survival analyses (32,33), which would focus on the first return visit, declining-effects modeling takes into account all return visits and allows for patients who may have more than one index visit. In this within-patient nesting modeling, patients serve as their own controls. Therefore, the design has the ability to control for a wide range of information related to the demographic and visit characteristics that are potential covariates while analyzing the impact of managed care on return visits to the psychiatric emergency service.

Mathematically, the Bernoulli hierarchical regression is

In the equation p is the probability that patient i will return on week t following the jth index visit. Iij=1 if the index visit occurred after managed care was implemented, and Iij=0 if the visit occurred before it was implemented. The symbol ui is a patient-level variate. The vector xij represents patient characteristics, with mean values xR.

When adjusted for mean characteristics (xR), the model allows investigators to estimate the expected probability that an average patient will have a return visit during the first week after the index visit either before (exp[β00]/[1+exp(β00)]) or after (exp [β00+ β01]/[1+exp (β00+β01)]) managed care was implemented. Expressed as an odds ratio, the difference in these adjusted rates measures the probability that managed care will affect rates of repeat visits during the first week after an index visit (exp[β01]). Rates of return visits are expected to decline (rate of exp[β10]) as time passes over the course of 26 weeks, both before and after managed care at a rate of (exp[β10+ β11]). The difference between the growth rates for pre- and post-managed care is the growth effect (exp[β11]), which accelerates or decelerates with time (rate of exp[β21]).

The estimated parameters were used to compute an adjusted cumulative probability that the average patient would have had at least one revisit by week t:

P(t)=1-[(1-p1)(1-p2)(1-p3) … (1-pt)]

With this model, multiple return visits for each patient over the 26 weeks after the index visit will lead to larger values of a cumulative probability.

Results

Between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2002, a total of 44,851 patients visited Parkland's psychiatric emergency service, generating 75,815 separate visits. Among these patients, 11,669 (26.02 percent) made at least one return visit within 26 weeks of a previous visit, accounting for 30,964 (40.8 percent) of the 75,815 visits. The interval between the index and the first return visit ranged from one day to 2,882 days. Of all study-defined repeat visits, 13.7 percent, 20.8 percent, 30.5 percent, and 63.0 percent were made within 1, 4, 8, and 26 weeks, respectively.

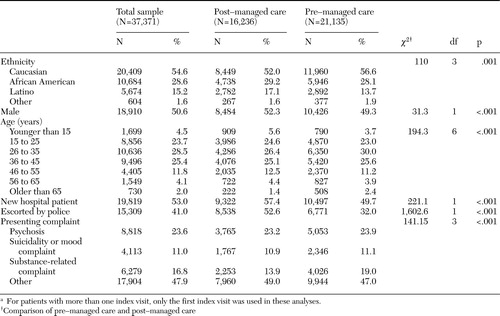

Using study-defined criteria for an index visit and requiring information on age to be present, we created a final analytic sample of 37,371 patients (83.3 percent of all patients): 21,135 in the pre-managed care group and 16,236 in the post-managed care group. Among the 37,371 patients, 2,271 (6 percent) made a return visit within one week, 3,106 (8 percent) within two weeks, 4,170 (11 percent) within four weeks, 5,162 (14 percent) within eight weeks, and 6,851 (18 percent) within 26 weeks. Compared with the excluded sample, the final analytic sample had more whites (20,409 whites, or 54.6 percent, compared with 3,940 whites, or 52.7 percent) and fewer African Americans (10,684 African Americans, or 28.6 percent, compared with 2,340 African Americans, or 31.3 percent) and Latinos (5,674 Latinos, or 15.2 percent, compared with 1,100 Latinos, or 14.7 percent) (χ2=24.91, df=3, p<.001). As shown in Table 1, rates of presentation for care by presenting complaint remained relatively stable across the two cohorts. However, visits for which the presenting complaint was the treatment of substance-related problems declined after NorthSTAR was implemented, and presentations in the "other" category increased by 4.1 percent.

Demographic and index visit characteristics

Gender and ethnicity. At the time of the index visit, males were slightly more likely than females to be new hospital patients (51.4 percent of males compared with 46.7 percent of females; χ2=85.14, df=1, p<.001, Yates continuity correction) and to be escorted by police (44.8 percent of males compared with 38.0 percent of females; χ2=194.99, df=1, p<.001). When the analyses were adjusted for age, ethnicity, and characteristics of the index visit (whether there was a police escort, whether the patient was new to the hospital, and whether managed care had been implemented), males were 37.7 percent more likely than females to have a return visit to the emergency department (odds ratio [OR]=1.38, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.33 to 1.42, p<.001). Male patients were more likely to revisit than female patients, both before managed care (OR=1.34, CI=1.29 to 1.41, p<.001) and after managed care (OR=1.41, CI=1.34 to 1.48, p<.001), and there was a 4.9 percent increase in the risk that males would enter psychiatric emergency services after managed care was implemented, although this result was nonsignificant.

African Americans were substantially less likely than the other ethnic groups, including Latinos, to present at the index visit as first-time hospital patients (29.0 percent of African Americans, compared with 57.4 percent of persons from other ethnic groups; χ2=2,691.57, df=1, p<.001). African Americans were not more likely than the other ethnic groups to be escorted by the police at the index presentation. After the analysis was adjusted for age, gender, and characteristics of the index visit, African Americans were more likely than whites to revisit the emergency department (OR=1.22, CI=1.17 to 1.27, p<.001). The risk of having a return visit did not vary significantly between African Americans and whites, either before or after managed care was implemented.

Latinos were slightly more likely than other ethnic groups to have their index visit be a first hospital encounter (55.7 percent of Latinos compared with 47.8 of persons from another ethnic group; χ2=120.48, df=1, p<.001). In addition, Latinos were somewhat less likely than other ethnic groups to present involuntarily for their index visit. After the analyses were adjusted for age, gender, and characteristics of the index visit, Latinos were not as likely as whites to have a return visit (OR=.79, CI=.75 to .83, p<.001). Following the implementation of managed care, revisit rates among Latinos increased compared with those of whites (pre-managed care, OR=.73, CI=.67 to .78, p<.001; post-managed care, OR=.85, CI=.80 to .92, p<.001; difference between pre- and post-managed care, OR=1.18, CI=1.06 to 1.31, p=.003).

In summary, males were 1.38 times as likely as females and African Americans were 1.22 times as likely as whites to have a repeat visit; the implementation of managed care did not produce a statistically significant difference in these risk factors. In contrast, before managed care was implemented, Latinos were only .78 times as likely as whites to have a return visit—a rate that increased to .85 after managed care was implemented. That is, managed care appears to have left unaffected the higher return rates found among African Americans and males, although it was associated with increased return rates among Latinos. Even so, after managed care was implemented, Latinos continued to have lower rates of return visits than whites.

Age. The association between age and return visits can be described as an inverted "U" shape, in which middle-aged patients (aged from 36 to 55 years) had the highest return rates, and very young and very old patients had the lowest rates. Specifically, children younger than 15 years and adults older than 65 years were less likely than middle-aged patients to return as patients (children younger than 15 years, OR=.78, CI=.72 to .85, p<.001; adults older than 65 years, OR=.78, CI=.69 to .87, p<.001). The effect size was smaller for young adults aged 15 to 25 years. Compared with their middle-aged counterparts, young adults aged 15 to 25 years were not as likely to make a repeat visit (OR=.95, CI=.905 to .989, t=2.43, p=.015).

Police escorts and first-time hospital visitors. As shown in Table 1, the proportion of patients accompanied by police on their first index visit increased significantly across the two periods (32.0 percent before managed care was implemented compared with 52.6 percent after managed care). However, these involuntary patients did not revisit the emergency department as often as voluntary patients. After the analyses were adjusted for other patient characteristics, patients who were escorted by the police to their index visit were not as likely to return as patients who presented voluntarily to their index visit (OR=.87, CI=.84 to .90, p<.001). By far, the most important predictor of return rates was whether the patient had previously used hospital services. Specifically, first-time users in both cohorts were not as likely to revisit as previous hospital patients (OR=.68, CI=.65 to .70, p<.001).

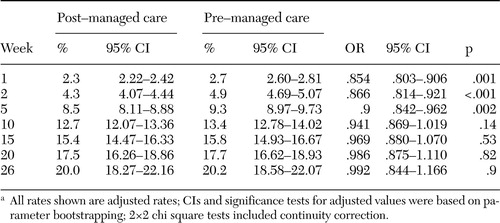

Return rates over time. When adjusted cumulative probabilities were tabulated, the referent patient had an adjusted first-week revisit rate of 2.70 percent before managed care was implemented (crude, unadjusted rate of 3.60 percent). After managed care was implemented, the referent patient had an adjusted first-week revisit rate of 2.32 percent (crude, unadjusted rate of 2.97 percent).

Weekly return rates (pt/[pt+1]) declined over time. The rate of initial decline before managed care was implemented was 81.8 percent of the rate of the previous week (exp[β10=.82, CI=.81 to .82, t=44.20, df=37,362, p<.001), while the rate of initial decline after managed care was implemented was 84.9 percent. Declining-effects analyses were also used to compare differences between pre- and post-managed care for patients with characteristics similar to those of the average patient in the referent population. We found that patients during post-managed care were 85 percent less likely to have a return visit than their pre-managed care counterparts (exp[β01]=.854, CI=.80 to .91, t=5.15, df=37,362, p<.001). (Note that the trivial difference in the 95 percent CI described in Table 2 is based on a parameter bootstrap, and the CI reported here is based on an exact estimate of the robust standard error taken from the covariance matrix of the estimated declining-effects model.) However, the post-managed care advantage did not appear to last over time, as post-managed care rates after a patient's index visit tended initially to increase by 1.04 percent per week more than the rates in the pre-managed care group: (exp[β11]=1.038, CI=1.02 to 1.05, t=5.63, df=37,362, p<.001), although this rate decelerated over time to only 99.87 percent of its preceding time rate (exp[β12]=.999, CI=.998 to .999, t=4.80, df=37,362, p<.001). Expressed another way, average time for managed care effects to expire following an index visit was 5.17 weeks (CI=2.537 to 9.148). This estimate was computed by solving the quadratic equation for time for the coefficients of the time and managed care interaction terms.

In short, post-managed care patients were only 85.3 percent as likely as their pre-managed care counterparts have had a return visit during the first week after an index emergency department visit (t=5.15, p<.001). However, this advantage seen in the post-managed care group did not extend to subsequent weeks after the patients' index visit. By 5.17 weeks after the index visit, the likelihood that a patient would return to the psychiatric emergency service for additional care was essentially the same before and after managed care (CI=2.54 to 9.15, p<.001).

As shown in Table 2, adjusted rates were computed for selected weeks after the index visit: weeks 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 26. (CIs and significance tests were determined on the basis of bootstrapping the parameters 20,000 times.) Although some effects of managed care on revisit rates were observed during the first ten weeks after the index visit, there were no observable effects of managed care after that point. In fact, differences in the likelihood of return visits occurred largely during weeks one through five after the index visit. At the end of 26 weeks, there were no differences between the pre- and post-managed care periods in the overall probability that the patient would have revisited the psychiatric emergency service. This finding suggests that this managed care system may merely delay, rather than prevent, return visits to the psychiatric emergency service.

Discussion

Because for-profit behavioral health systems are increasingly associated with capitated public mental health care delivery, it is extremely important to develop appropriate indicators that help monitor the provision of care to the most vulnerable among persons with mental illness (34,35). This article describes one updated tool: a measure of psychiatric emergency service revisit rates, which provides information about the impact of managed care on patterns of service use.

Previous attempts by managed care to reduce reliance on emergency services by increasing access to alternative providers have encountered mixed results (36,37,38,39,40). Our study supports the conclusions of some that it is possible, under managed mental health delivery structures, to shift a portion of the balance of care away from emergency departments, affording consumers increased continuity of care in specialty settings while reducing the high cost associated with treatment in emergency settings (41,42,43).

In this and other recent analyses the length of inpatient stay declined under managed care, but shorter stays did not precipitate increased post-discharge revisit rates to the psychiatric emergency department among poorly stabilized patients (42,43). However, when stays for psychiatric inpatients become as brief as they are now, there may no longer be a relationship between length of hospitalization and emergency department visits made shortly after discharge (44). Thus additional work is needed to determine whether visits to the psychiatric emergency service after inpatient stays continue to be a valid indicator of quality of care.

Penetration rates, defined as the percentage of eligible individuals who actually used services, under NorthSTAR were higher than in surrounding areas that did not implement NorthSTAR (45). Yet after managed care was implemented, high and stable revisit rates were observed among males, African Americans, and those who had previously used emergency services—patient groups that outpatient care has historically found difficult to engage (46,47,48,49) and for whom managed care may not provide equal or adequate access (50,51,52,53). These patient groups are those upon whom chronic mental illness takes its biggest toll (54), and patients with more severe and persistent mental illness have traditionally not fared well under managed care structures (4,55,56,57). Although our analyses did not reveal markers that suggested that these important patient groups have been grossly neglected under managed care, their revisit rates, combined with increasing rates of visits in which patients were brought to the emergency department by police, may indicate a failure of the outpatient care structure to accommodate persons with intractable illness.

In this study, a patient with multiple visits to the emergency department without a 26-week lapse between visits was understood to be experiencing a protracted illness episode for which nonemergency alternative care was not succeeding. These assumptions about the failure of alternative care and the length of an episode of illness obviously cannot go unchallenged. In particular, the notion that a "new" illness episode is associated with the absence of an emergency department visit for a minimum of 180 days is arbitrary. Here, this operational definition allows certain emergency visits to be considered part of a new-onset illness episode without penalty to the system providing non-emergency care.

This study's observational, single-center nature and the lack of modeling of some aspects of illness and psychiatric emergency help-seeking behavior (for example, diagnostic groups, medical and psychiatric comorbid conditions, and payer status) represent further limitations. However, the addition of three "front door" crisis sites 20 months after managed care was implemented did not eliminate the finding of delayed, resurgent rates of revisits, suggesting that study findings are likely robust and even understated. In effect, patients from some consumer groups who had previously used psychiatric emergency services (for example, persons with more chronic and severe illness) appear to have initially tried the new system of care but to have slipped back into old care-seeking patterns shortly thereafter, within months of exposure to the new model.

Conclusions

Determining the relative success of complex and rapidly evolving managed care structures that use public funds to treat persons with mental illness will require ongoing, multidimensional assessment (3,4). In this analysis, managed care with its concomitant emphasis on reduced inpatient, and increased outpatient, care provision did not result in increased rates of bounceback psychiatric emergency visits as expected. However, neither did it slow the rising numbers of visits during which the patient was accompanied by the police. While improved access to alternative care appears to have delayed the next crisis visit for many, it did not eliminate these visits for all. Further comparisons of revisit rates to the psychiatric emergency service among specific groups before and after managed care was implemented may provide specific information about persons who benefit from such systemic changes and those who do not.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Mental Health Connections, a partnership between what was formerly the Texas State Mental Health and Mental Retardation Service and the department of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, which receives funding from the Texas State Legislature and the Dallas County Hospital District. The authors appreciate the consultation of Wendy Waddell, M.S.N., R.N., Cynthia McDonald, and Judy Thompson. They are also grateful to the following persons for providing information about NorthSTAR that is not available in published form: John Theiss, Ph.D., David Young, and James Baker, M.D. Finally, the authors thank Larry Thornton, M.D., for providing statistics on the decline in length of inpatient stay after the introduction of NorthSTAR into the study hospital catchment area.

Dr. Claassen, Dr. Kashner, Dr. Gilfillan, and Dr. Rush are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and Dr. Larkin is with the department of surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Dr. Gilfillan is also with psychiatric emergency services at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas. Send correspondence to Dr. Claassen at 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, Texas 75390 (e-mail, [email protected])

|

Table 1. Characteristics of persons who visited a psychiatric emergency service, by managed care status of the emergency department during the first index visita

aFor patients with more than one index visit, only the first index visit was used in these analyses.

|

Table 2. Differences in adjusted cumulative likelihood of returning to a psychiatric emergency service in the weeks after the index psychiatric emergency service visit, by managed care status of the psychiatric emergency service during the index visita

aAll rates shown are adjusted rates; CIs and significance tests for adjusted values were based on parameter bootstrapping; 2×2 chi square tests included continuity correction.

1. State Mental Health Agency Relationship to Medicaid for Funding and Organizing Mental Health Services:2002–2003. State Profile Highlights no 04–14. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute, Inc, March2004. Available at www.nri-inc.org/profiles02/14medicaid.pdfGoogle Scholar

2. Peck R: Providers size up managed care. Behavioral Health Management 14:16,1994Google Scholar

3. Hoge MA, Jacobs S, Thakur NM, et al: Ten dimensions of public-sector managed care. Psychiatric Services 50:51–55,1999Link, Google Scholar

4. Bouchery E, Harwood H: The Nebraska Medicaid managed behavioral health care initiative: impacts on utilization, expenditures, and quality of care for mental health. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:93–108,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hutchinson AB, Foster EM: The effect of Medicaid managed care on mental health care for children: a review of the literature. Mental Health Services Research 5:39–54,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Levy ME, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, et al: Quality measurement and accountability for substance abuse and mental health services in managed care organizations. Medical Care 40:1238–1248,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. May AR: Mental Health Services in Europe. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1976Google Scholar

8. Bristol JH, Giller E Jr, Docherty JP: Trends in emergency psychiatry in the last two decades. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:623–628,1981Link, Google Scholar

9. Kastrup M, Dupont A: Who became revolving door patients? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia 76:80–88,1987Google Scholar

10. Catalano R, McConnell W, Forster P, et al: Psychiatric emergency services and the system of care. Psychiatric Services 54:351–355,2003Link, Google Scholar

11. White-Means SI, Thornton MC: Nonemergency visits to hospital emergency rooms: a comparison of blacks and whites. Milbank Quarterly 67:35–571989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Solomon P, Beck S: Patient's perceived needs when seen in a psychiatric emergency room. Psychiatric Quarterly 60:215–226,1989.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Claassen CA, Hughes CW, Gilfillan S, et al: Toward a redefinition of psychiatric emergency. Health Services Research 35:735–754,2000.Medline, Google Scholar

14. Purdie FRJ, Honigman B, Rosen P: The chronic emergency department patient. Annals of Emergency Medicine 10:298–302,1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Segal SP, Akutsu PD, Watson MA: Factors associated with involuntary return to a psychiatric emergency service within 12 months. Psychiatric Services 49:1212–1217,1998Link, Google Scholar

16. Perez E, Minoletti A, Blouin J, et al: Repeated users of a psychiatric emergency service in a Canadian general hospital. Psychiatric Quarterly 58:189–201,1986–1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Andren KB, Rosenqvist U: Heavy users of an emergency department: a two year follow-up study. Social Science and Medicine, 25:825–831,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Gillig PM, Grubb P, Kruger R, et al: What do psychiatric emergency patients really want and how do they feel about what they get? Psychiatric Quarterly 61:189–196,1990Google Scholar

19. Kastrup M: Who became revolving door patients? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia 76:80–88,1987Google Scholar

20. Ross EC: Will managed care ever deliver on its promises? Managed care, public policy, and consumers of mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 28:7–22,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mowbay CT, Grazier KL, Holter M: Managed behavioral health care in the public sector: will it become the third shame of the states? Psychiatric Services 53:157–170,2002Google Scholar

22. Busch AB, Frank RG, Lehman AF: The effect of a managed behavioral health carve-out on quality of care for Medicaid patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:442–448,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Morrissey JP, Goldman HH: Care and treatment of the mentally ill in the United States: historical developments and reforms. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 484:12–27,1986Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Palmero GB: Transinstitutionalization and an overburdened judicial system. Medicine and the Law 17:77–82,1998Medline, Google Scholar

25. Fisher WH, Dickey B, Normand SL, et al: Use of a state inpatient forensic system under managed mental health care. Psychiatric Services 53:447–451,2002Link, Google Scholar

26. NorthSTAR Homepage, 2004. Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation. Available at www.dshs.state.tx.us/mhprograms/northstarhomepage.shtmGoogle Scholar

27. Innovations in American Government: 2001 Semifinalist Application. Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation. Available at www.dshs.state.tx.us/mhprograms/innovations_2001_semi_finalist_application.pdfGoogle Scholar

28. NorthSTAR Quarterly Data Book: Fourth Quarter: SFY 2004: September 2004. Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, Austin, Tex, 2001. Available at www.dshs.state.tx.us/mhprograms/northstar_data_book.pdfGoogle Scholar

29. Kashner TM, Carmody TJ, Suppes, et al: Catching-up on health outcomes: the Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Health Services Research 38:311–331,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Kashner TM, Rosenheck R, Campinell AB, et al: Impact of work therapy on health status among homeless, substance dependent veterans: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:938–944,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Suppes S, Rush AJ, Dennehy EB, et al: Texas Medication Algorithm Project, phase 3 (TMAP): clinical results for patients with a history of mania. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:370–382,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Harrell FE: Regression Modeling Strategies With Application to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York, Springer, 2001Google Scholar

33. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data. New York, Wiley-Interscience, 1999Google Scholar

34. Mechanic D, Bilder S: Treatment of people with mental illness: a decade-long perspective. Health Affairs 23(4):84–95,2004Google Scholar

35. Robinson JE, Clay T: Protecting the public interests: issues in contracting managed behavioral health. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration 25:452–470,2003Medline, Google Scholar

36. Kravitz RL, Azanziger J, Hosek S: Effect of a large managed care program on emergency department use: results from the CHAMPUS reform initiative evaluation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 31:741–748,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Roberts E, Mays N: Can primary care and community-based models of emergency care substitute for the hospital accident and emergency (A&E) department? Health Policy 44:191–214,1998Google Scholar

38. Piehl M, Clemens C, Joines J: Narrowing the gap: decreasing emergency department use by children enrolled in the Medicaid program by improving access to primary care. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 154:791–795,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Washington D, Stevens CD, Shekelle PG: Next-day care for emergency department users with nonacute conditions. Annals of Internal Medicine 137:707–714,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Waitzkin H, Williams RL, Bock JA, et al: Safety-net institutions buffer the impact of Medicaid managed care: a multi-method assessment in a rural state. American Journal of Public Health 92:598–610,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Wingerson D, Russo J, Ries R, et al: Use of psychiatric emergency services and enrollment status in a public managed mental health care plan. Psychiatric Services 52:1494–1501,2001Link, Google Scholar

42. Dickey BEC, Norton S, Normand H, et al: Massachusetts Medicaid Managed Care Health Care Reform: treatment for the psychiatrically disabled. Advances in Health Economics and Health Research 15:99–116,1995Medline, Google Scholar

43. Dickey B, Normand ST, Norton ED, et al: Managing the care of schizophrenia: lessons from a 4-year Massachusetts Medicaid Study. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:945–952,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Segal SP, Akutsu PD, Watson MA: Factors associated with involuntary return to a psychiatric emergency service within 12 months. Psychiatric Services 49:1212–1217,1998Link, Google Scholar

45. Report to the Board: Dallas Area NorthSTAR Authority. Dallas Area NorthSTAR Authority, March 2004. Available at www.dansatx.org/docs/jttreport.pdfGoogle Scholar

46. Andren KG, Rosenqvist U: Heavy users of an emergency department: psycho-social and medical characteristics, other health contacts, and the effect of a hospital social worker intervention. Social Science and Medicine 21:761–770,1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Backrach LI: The effects of deinstitutionalization on general hospital psychiatry. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 32:786–790,1981Abstract, Google Scholar

48. Canton CLM: The new chronic patient: clinical characteristics of an emerging subgroup. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 323:471–474,1981Google Scholar

49. Geller MP: The "revolving door": a trap or a lifestyle? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:388–389,1982Google Scholar

50. Virnig B, Huang Z, Lurie N, et al: Does Medicare managed care provide equal treatment for mental illness across races? Archives of General Psychiatry 61:201–205,2004Google Scholar

51. Stiles PG, Boothroyd RA, Snyder K, et al: Service penetration by persons with severe mental illness: how should it be measured? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 29:198–207,2002Google Scholar

52. Alegria M, McGuire T, Vera M, et al: Does managed mental health care reallocate resources to those with greater need for services? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 28:439–455,2001Google Scholar

53. Wingerson D, Russo J, Ries R, et al: Use of psychiatric emergency services and enrollment status in a public managed mental health care plan. Psychiatric Services 52:1494–1501,2001Link, Google Scholar

54. Canton CL, Goldstein J: Housing change of chronic schizophrenic patients: a consequence of the revolving door. Social Science and Medicine 19:759–764,1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Hellinger F: The effect of managed care on quality. Archives of Internal Medicine 158:833–841,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Lurie N, Christianson JB, Gray DZ, et al: The effect of the Utah Prepaid Mental Health Plan on structure, process, and outcomes of care. New Directions for Mental Health Services 78:99–106,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Scheid TL: Managed care and the rationalization of mental health services. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44:142–61,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar