Characteristics of Third-Party Money Management for Persons With Psychiatric Disabilities

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined different types of third-party money management arrangements for persons with psychiatric disabilities and consumers' perceptions of their finances in the context of these arrangements. METHODS: Clinical and demographic data were collected through structured interviews and record reviews for 240 persons with a diagnosis of a psychotic or major affective disorder who had been involuntarily hospitalized and were awaiting discharge on outpatient commitment in North Carolina. All consumers were receiving Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance. RESULTS: Third-party money management arrangements were reported by 102 (41 percent) of the study participants. A majority (77 percent) of these consumers had their finances managed by a family member. Consumers with third-party money managers were more likely to have a median annual income below $5,000, to have a diagnosis of a primary psychotic disorder, and to have substance use problems. Most participants with third-party money managers reported that they received sufficient money to cover basic expenses, although about half also perceived having insufficient money to participate in enjoyable activities. CONCLUSIONS: Given that treatment for severe mental illness emphasizes social skills training and development of social support networks, financial limitations could undermine therapeutic efforts. It is important that clinicians consider the role of financial concerns when assessing consumers. Additional research should be conducted to better understand the role of financial variables in providing effective mental health services.

Persons with psychiatric disabilities frequently have their finances managed by third parties. Since the early 1990s, more than a quarter of recipients of Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) have qualified for these benefits because of a mental disorder (1). Although many persons with psychiatric disabilities receive support from public entitlements, some may have cognitive deficits that impair their ability to manage their money (2). Furthermore, there is concern that recipients may use benefits to purchase illicit substances (3,4,5).

To avoid these potential problems, the Social Security Administration can assign a formal third-party money manager, called a representative payee, for recipients who show an inability to manage their finances (2,6). A representative payee can be either an agency or a person who is paid directly by the Social Security Administration and through whom a recipient gains access to his or her disability payments.

The use of third-party money managers to assist persons with psychiatric disability in managing their money has proliferated in the past decade. Some data indicate that third-party money managers are designated for about half of persons who receive disability benefits for mental disorders (7). Among persons who responded to one survey of community mental health centers in Washington State, 73 percent reported providing formal representative payee services (8). Some recent studies have shown that persons with mental illness who have such representative payees are less likely to become homeless (9), experience less victimization (10), have greater participation in treatment (10,11), and spend fewer days in psychiatric hospitals (9,12). The impact on substance use of having third-party money management among persons with mental illness is less clear—some studies show decreased substance use (13), whereas others show no relationship (9,14).

Although theses studies suggest that there is potential for third-party money management relationships to have an impact on mental health services, few studies have examined the characteristics of money management arrangements themselves. Most of the extant research has been conducted in conjunction with formal representative payee programs at mental health centers (8, 10,11,12,15). However, there may be persons with mental disabilities who do not have formal representative payees but have other informal third-party arrangements. Furthermore, various individuals can manage consumers' money, such as the consumer's clinician or parents (13). Because of the different relationships a consumer might have with his or her payee, it is probable that consumers' level of support from family or service providers would be affected by issues surrounding the allocation of the consumer's monthly disability funds. Consequently, different money management arrangements could have therapeutic relevance, especially for case management purposes.

Rosenheck (16) notes that differences in third-party money management arrangements have received little attention in the empirical literature. A number of questions remain unaddressed. Are certain clinical or demographic characteristics associated with having a third-party money manager? What characteristics differentiate individuals who have formal and informal arrangements? How does the identity of the payee affect money management arrangements? Do third-party money management arrangements affect how consumers perceive their finances?

To our knowledge, no study has investigated different money management arrangements or examined consumers' perceptions of their financial situation. Monahan and colleagues (17) recommend that descriptive research be conducted to fundamentally explore the relationship between money management and mental health services. By doing so, we can understand more about who is receiving the reported treatment benefits of third-party money management (9,10,11,12).

The purpose of this study was to address the aforementioned questions and to elucidate the different types of money management arrangements and consumers' perceptions of their finances in the context of these arrangements.

Methods

Sample

Data were collected as part of a randomized study of the effectiveness of outpatient commitment of persons with severe mental illness (18). The analysis presented here used baseline assessments made before random assignment. The respondents were patients who had been involuntarily admitted to one of four hospitals and who were awaiting discharge on outpatient commitment to one of nine counties in north central North Carolina between November 1992 and March 1996. Formal eligibility criteria were involuntary hospital admission, age of at least 18 years, diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or a major affective disorder, and current receipt of SSI or SSDI.

After institutional review board approval was obtained, potentially eligible participants were identified from daily hospital admission records. While these individuals were still hospitalized, research staff met with them to describe the study and to obtain their consent to participate. Of identified eligible consumers, about 12 percent refused to participate in the study. Rates of refusal did not significantly vary by sex, race, or diagnosis.

It is important to note that this sample does not necessarily represent all persons with serious mental illness but would generalize more narrowly to persons with serious mental illness who have recently experienced involuntary hospital admission and would meet North Carolina criteria for outpatient commitment (indication of danger to self or other, including grave disablement). The study participants resemble populations that are sometimes referred to as revolving-door consumers—persons with a history of admissions to a state mental hospital who are deemed likely to decompensate to a point of compromised safety without ongoing treatment in the community and whose illness impairs their ability to seek and adhere voluntarily to recommended treatment.

Measures

Demographic and clinical information was collected during interviews with the study participants, their family members, and clinicians and from a systematic review of hospital records, which involved examination of clinical assessments, treatment progress notes, and the legal section of the chart. Data on homelessness, fights or violence, and past hospitalizations were collected from these sources. Substance use was defined as any use of alcohol or illicit drugs at least occasionally during the four months before hospital admission. Psychiatric symptoms were assessed with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (19). Functional impairment was measured with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (20), coded systematically by clinical research interviewers trained to a high degree of interrater reliability. A composite index of medication adherence was computed as the average frequency of adherence as reported by three interview sources—the study participant, the family member, and the case manager. This measure as well as its association with clinical and social characteristics has been discussed in detail previously (18).

Third-party money management information included data on whether the persons received SSI or SSDI and whether a third party managed his or her disabilities checks. If the consumer reported any type of third-party money management arrangement, he or she was asked who the third party was, including whether the payee was a family member (a parent, a spouse, or another relative) or a nonrelative (a legal guardian, a mental health professional, or another person, such as clergy or friend). Consumers were considered to have a formal money management arrangement if they reported having a representative payee, whereas consumers were considered to have an informal money management arrangement if they reported that they managed their own money and did not have a representative payee. Finally, the consumers rated whether they perceived that they had sufficient money to cover food, clothing, housing, transportation, and social activities.

Analysis

Data were collected from these multiple sources and entered onto SAS version 8.0. When data were skewed, Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney nonparametric procedures were used to test for group differences. For example, functional impairment based on GAF scores indicated a skewed distribution when analyzed. Thus GAF scores were transformed into a dichotomous variable (above or below the median).

The following analyses were conducted. First, descriptive analyses reporting clinical and demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented. Second, chi square analyses compared consumers who self-managed their disability benefits with those who had third-party money managers. Third, descriptive analyses were used to elucidate who managed disability checks among persons with third-party money managers, whether these arrangements were formal or informal, and the consumers' perceptions of their financial arrangements.

Finally, logistic regression analysis applying backwards stepwise elimination procedures to a series of staged regressions was employed. Independent variables—demographic characteristics, clinical data, and perceptions of finances—were regressed onto the following dependent variables: whether consumers had a third-party money manager, whether the third-party money manager was a family member, and whether the consumer had a formal money management arrangement. Stepwise elimination procedures using a .15 probability inclusion level and a .10 probability exclusion level were employed. Odds ratios (ORs) produced by this technique estimate the average change in the odds of a predicted outcome, such as having a third-party money manager, associated with exposure to independent variables, such as medication adherence. The log likelihood chi square tests the overall significance of a given logistic regression model, and the pseudo R2 statistic estimates the percent of variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the model.

Results

A total of 164 study participants (68 percent) were African American, and 76 (32 percent) were Caucasian. A total of 104 participants (43 percent) were women, and 136 (57 percent) were men. Although a majority of the participants lived in urban locations (149 participants, or 62 percent), a substantial proportion lived in rural areas and small towns. Approximately half the sample was between the ages of 18 and 39 years (125 participants, or 52 percent). Most of the consumers were single (197 participants, or 82 percent). A minority of the sample had recently been homeless before recruitment into the study (50 participants, or 21 percent).

Almost three-quarters of the respondents (177 participants, or 74 percent) had diagnoses of primary thought disorders (psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder), and the remainder (63 participants, or 26 percent) had primary affective disorders (mood disorders, such as depressive and bipolar disorder). Approximately a third of the sample (80 participants, or 33 percent) had comorbid substance use disorders. About half reported that they had engaged in a verbal or physical fight in the previous year (123 participants, or 51 percent), and half reported having at least two psychiatric admissions in the previous year (123 participants, or 51 percent). The large majority (177 participants, or 74 percent) had not been adherent to prescribed medication regimens during the four months before enrollment in the study, according to a composite generated from self-report, clinician-report, and family-report.

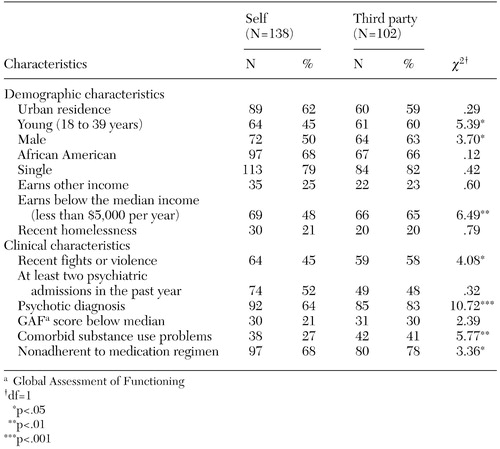

A total of 138 study participants (58 percent) managed their own SSI or SSDI benefits, and 102 (42 percent) reported that they had their disability checks managed by others. Demographic and clinical characteristics of consumers who managed their money themselves and those who had third-party money management arrangements are summarized in Table 1. Bivariate relationships showed that consumers with third-party money managers were more likely to be younger, to be male, to have a median annual income below $5,000, to report recent fights or violence, to have a psychotic diagnosis, to have substance use problems, and to be nonadherent to psychotropic medication regimens. It is important to note that consumers' perceptions of financial arrangements did not differ by whether they managed their own money; thus these results are not illustrated in the table.

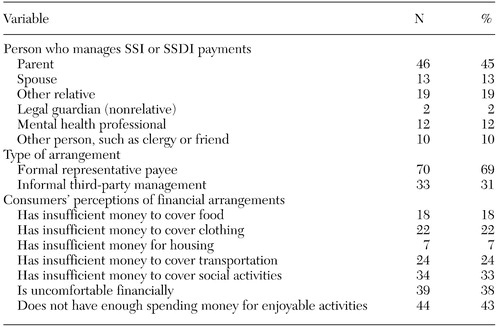

Characteristics of third-party money management arrangements in the sample are summarized in Table 2. A majority of these consumers had their money managed by family members (78 consumers, or 77 percent), most commonly a parent (45 percent), a spouse (13 percent), or another relative (19 percent). Only ten consumers had their money managed by mental health professionals. With respect to type of arrangement, 69 percent of the consumers indicated that they had formal representative payee arrangements, whereas 31 percent indicated that they had informal payee arrangements.

To determine whether family arrangements tended to be formal or informal, family as opposed to a nonrelative, and formal as opposed to informal, cross-tabulations were performed but did not yield a statistically significant association. Overall, only a minority of consumers with representative payee arrangements complained of having insufficient money to cover food (18 percent), clothing (22 percent), housing (7 percent), and transportation (24 percent). However, a third reported having insufficient money to cover social activities, 38 percent reported being "uncomfortable" financially, and 43 percent indicated that they did not have enough spending money for enjoyable activities.

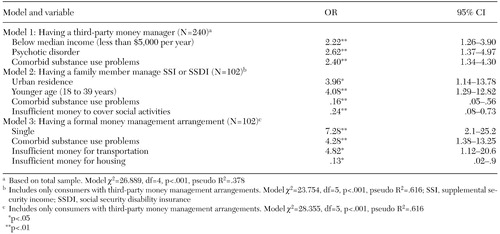

Backwards stepwise multiple logistic regression was used to examine the net association of various factors with three different money management arrangements (Table 3). The first model, which included the entire sample of 240 consumers, explored the factors associated with having a third-party money manager. This model was statistically significant. Having a median income below $5,000 per year (OR=2.22), having a primary thought disorder (OR=2.62), and having substance use problems (OR=2.40) were associated with increased odds of having a third-party money manager.

The second model, which included only consumers who had third-party money management arrangements (N=102), explored the factors associated with having a family member manage SSI or SSDI benefits. This model was statistically significant. Residing in an urban setting (OR=3.96) and being younger (OR=4.08) were associated with increased odds of having a family member manage money. On the other hand, family members were significantly less likely to be money managers for consumers who had substance use problems (OR=.16) than for those who did not. Also, consumers who had family members as third-party money managers were more likely to report that they had enough money to cover social activities (OR=.24) than consumers whose third-party money managers were nonrelatives.

The third model, which also included only consumers who had third-party money management arrangements (N=102), explored the factors associated with having a formal money management arrangement. This model was statistically significant. Being single (OR=7.28) and having substance use problems (OR=4.28) increased the chances that the third-party money management arrangement was formal. Consumers who had formal arrangements were more likely to report that they had insufficient money for transportation (OR=4.82) but were less likely to report that they had insufficient money for housing (OR=.13) than consumers who had informal money management arrangements.

Discussion and conclusions

Third-party money management arrangements were reported by 41 percent of the consumers in our study sample and were found to be associated with low income, comorbid substance use problems, and presence of a primary psychotic disorder. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies showing that substance use (8) and presence of a primary psychotic disorder (16) were related to having a third-party money manager. Among the study participants who had third-party money managers, most agreed that they had enough money to cover necessities, such as food, clothing, and transportation.

However, about half of all the consumers reported feeling uncomfortable financially. Specifically, a third of the consumers indicated that they had insufficient money to cover social activities, and 43 percent reported feeling they did not have enough spending money for enjoyable activities. Given that treatment for severe mental illness emphasizes social skills training and development of social support networks, the findings signal that financial constraints could undermine therapeutic efforts. It is therefore important that clinicians consider the role of financial concerns when assessing whether their consumers are becoming isolated secondary to exacerbation of symptoms or are unable to engage in social activities simply because of an insufficiency of funds.

Family members were the most frequent type of third-party money manager, especially among consumers who lived in urban settings and were aged 18 to 39 years, who would perhaps be the most likely to be financially dependent on parents and family. Families seemed to be less involved with third-party money management in the case of consumers with comorbid substance use problems. It is possible that consumers who use money to maintain drug or alcohol habits "burn bridges" with family members who are wary of being involved with the consumers' finances.

Consumers who had family members as money managers more often reported having enough money to cover their expenses, in contrast with consumers whose money managers were nonrelatives, which suggests that families may supplement consumers' funds to encourage them to establish friendships outside the home. Consumers with family member money managers more often reported having enough money to cover their social activities, compared with consumers with nonrelative money managers. The reason for this is unclear, although this finding may suggest that families supplement consumers' funds to encourage them to engage in activities and establish relationships outside the home. On the other hand, one downside to this arrangement is the potential for family members to exploit consumers. For example, if a consumer lives with his payee parents and the family is impoverished, the consumer's SSI check may be the only stable source of income in the household. Although case managers need to be alert for therapeutic issues involving coercion that could arise from family payee arrangements, they should be aware that the data from this study suggest some reported benefits of having family manage money.

Our findings suggest that there is a subset of consumers with informal money arrangements who are clinically and demographically distinct from consumers who have formal arrangements. Although formal arrangements were associated with being single and having a comorbid substance use disorder, they were also associated with a perceived insufficiency of funds for transportation. Conversely, informal arrangements were associated with a perception of not having enough money for housing. One could speculate that consumers with formal money management relationships are more closely linked with mental health service systems. Thus these consumers would be placed in residential settings and would not need to worry about money for rent. However, it is not clear what accounts for these differences. This study simply revealed for the first time that consumers may have their SSI or SSDI managed by people who are not representative payees.

Knowledge of both types of arrangements is important to treatment providers, because informal arrangements have less accountability for payees and thereby could expose consumers to a greater risk of having their money misused. For example, if a landlord receives a consumer's SSI check and is not a representative payee, there is no legal documentation stating that the landlord must legally give that money minus the rent to the consumer. Thus formal arrangements are likely to reduce the likelihood of such a conflict of interest, because the boundaries and expectations are made clear. For this reason, behavioral principles of contingency management would predict that formal representative payee arrangements provide better leverage for encouraging adherence than informal arrangements (13,21).

It should be noted that we studied a sample of persons with serious mental illness and that relatively few clinicians were reported to be representative payees. Thus caution must be used in generalizing the results of the study. In addition, the availability of money management services may vary by mental health system, which may affect which consumers have third-party money management arrangements. Given that previous research has chiefly examined formal representative payee programs at mental health centers, future studies should attempt to determine whether or how individuals might "fall through the cracks" and end up with informal arrangements. Furthermore, because few consumers in this study indicated that mental health professionals managed their money, future research would ideally explore the treatment implications of a wider array of money management arrangements.

Given the aforementioned ways in which finances might affect treatment goals and case management, the treatment implications of a wider array of money management arrangements require further investigation and clarification. Without such research, it will be unknown to what extent financial arrangements undermine treatment of persons with serious mental illness or how financial arrangements can be clinically utilized to enhance treatment outcome (16,17). Consequently, examining third-party money management arrangements underscores the need to better understand the role of financial variables in providing effective mental health services.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (grants MH-48103 and MH-51410) and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The authors are affiliated with the services effectiveness research program in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University Medical Center, Box 3071, Durham, North Carolina 27710 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of consumers who managed their own disability payments and those whose payments were managed by a third party

|

Table 2. Characteristics of 102 consumers with third-party money management arrangements for their Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)

|

Table 3. Stepwise logistic regression models of factors associated with third-party money management arrangements

1. Kochhar SM, Scott CG: Disability patterns among SSI recipients. Social Security Bulletin 58:3–14, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

2. Brotman AW, Muller JJ: The therapist as representative payee. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:167–171, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Satel S: When disability benefits make patients sicker. New England Journal of Medicine 333:794–796Google Scholar

4. Shaner A, Eckman TA, Roberts LJ, et al: Disability income, cocaine use, and repeated hospitalization among schizophrenic cocaine abusers: a government-sponsored revolving door? New England Journal of Medicine 333:777–783, 1995Google Scholar

5. Satel S, Reuter S, Hartley D, et al: Influence of retroactive disability payments on recipients' compliance with substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services 48:796–799, 1997Link, Google Scholar

6. Rosen MI, Rosenheck R: Substance use and assignment of representative payees. Psychiatric Services 50:95–98, 1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Dixon L, Turner J, Kraus N, et al: Case managers' and clients' perspectives on a representative payee program. Psychiatric Services 60:781–786, 1999Link, Google Scholar

8. Ries RK, Dyck DG: Representative payee practices of community mental health centers in Washington State. Psychiatric Services 48:811–814, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Rosenheck R, Lam J, Randolph F: Impact of representative payees on substance abuse by homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:800–806, 1997Link, Google Scholar

10. Stoner MR: Money management services for the homeless mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:751–753, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Ries R, Comtois KA: Managing disability benefits as part of treatment for persons with severe mental illness and co-morbid drug/alcohol disorders: a comparative study of payee and non-payee participants. American Journal of Addictions 6:330–338, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

12. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Conrad KJ, et al: An agency-based representative payee program and improved community tenure of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:1218–1222, 1998Link, Google Scholar

13. Shaner A, Roberts LJ, Eckman TA, et al: Monetary reinforcement of abstinence from cocaine among mentally ill patients with cocaine dependence. Psychiatric Services 48:807–814, 1997Link, Google Scholar

14. Frisman LK, Rosenheck R: The relationship of public support payments to substance abuse among homeless veterans with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:792–795, 1997Link, Google Scholar

15. Conrad KJ, Matters MD, Hanrahan P, et al: Characteristics of persons with mental illness in a representative payee program. Psychiatric Services 49:1223–1225, 1998Link, Google Scholar

16. Rosenheck R: Disability payments and chemical dependence: conflicting values and uncertain effects. Psychiatric Services 48:789–791, 1997Link, Google Scholar

17. Monahan J, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Mandated community treatment: beyond outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 52:1198–1205, 2001Link, Google Scholar

18. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, et al: Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce hospital recidivism? Findings from a randomized trial with severely mentally ill individuals. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1968–1975, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Derogatis L, Melisaratos N: The Brief Symptom Inventory: a brief report. Psychological Medicine 13:595–605, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Endicott J, Spitzer R, Fleiss J, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbances. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766–771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Elbogen EB, Tomkins AJ: From the hospital to the community: integrating contingency management and conditional release. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 20:427–444, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar