Physicians' and Patients' Involvement in Relapse Prevention With Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia

Abstract

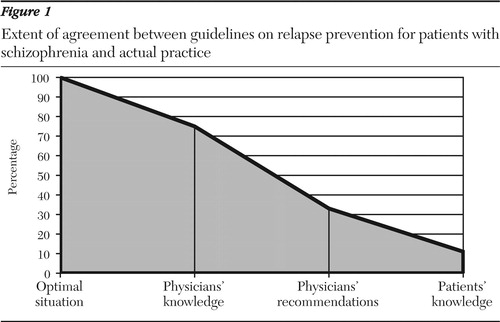

The purpose of this study was to assess the current status of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Fifty hospital psychiatrists in Germany were interviewed about 100 currently treated inpatients. The patients were also interviewed about their knowledge of maintenance therapy. For 75 percent of their patients, physicians fulfilled guideline recommendations when indicating the planned duration of antipsychotic maintenance therapy. However, these recommendations were not routinely communicated to the patients, and target interventions, such as psychoeducation, to guarantee continuous antipsychotic therapy were seldom used. Accordingly, patients' knowledge of the optimal duration of maintenance therapy was poor.

Maintenance therapy with antipsychotic medication reduces relapse rates among patients with schizophrenia (1). However, studies that were conducted ten years ago showed that physicians' noncompliance—that is, failure to prescribe antipsychotics by guideline recommendations when such medications are indicated—means that only a small proportion of patients actually receive optimal maintenance therapy (2,3). In the study reported here we investigated the current state of maintenance therapy in a naturalistic setting.

Methods

The study was introduced at morning rounds in eight psychiatric hospitals in South Germany. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Technische Universität München. Psychiatrists who were willing to participate were included in the study if they were currently treating inpatients with schizophrenia. For two patients per physician who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and who were to be discharged next (there were no exclusion criteria), sociodemographic variables, Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (4) scores, medication, and interventions to improve medication adherence were documented (N=100 patients). The physicians were asked about these patients' treatment adherence before admission and maintenance therapy for the time after discharge. Psychiatrists rated the patients' treatment adherence before admission on a 4-point adherence scale with well-defined anchor points that had been successfully used in a previous study (5). Adherence was dichotomized as good or poor.

The 100 patients were asked to provide written consent to participate in the interviews, and 92 agreed. These patients were asked whether physicians discussed the subject of antipsychotic maintenance therapy with them, what they were told, and whether they intended to continue with therapy after discharge.

Frequency statistics were calculated for all variables of interest. Univariate associations of sociodemographic data as well as illness-related factors with variables of interest were analyzed. All tests were two sided; those for which p values were below .05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

We interviewed 50 psychiatrists (30 men and 20 women, with a mean±SD age of 39.4±7.4 years and 8.1±6.4 years of experience in the field of psychiatry). Sixteen of these psychiatrists were working in closed wards, and all the others were on open wards. The patient sample consisted of 60 men and 40 women, all white, with a mean age of 38.1±10.9 years. Fourteen patients had a first episode (no previous hospitalizations and no previous antipsychotic medication), and 86 had had multiple episodes. Twenty-three patients had zero or one previous hospitalization, 42 patients had two to five hospitalizations, and 35 had more than five hospitalizations. Only 25 patients were employed; 34 were unemployed, seven were students or trainees, and 27 were retired; the employment status of seven patients was unspecified.

According to the German Psychiatric Association's Guidelines for the Treatment of Schizophrenia (6), which are similar to the guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association, 12 to 24 months of relapse prevention was appropriate for the 14 first-episode patients in our sample, and at least four years was appropriate for the remaining 86 patients.

When psychiatrists were asked about the theoretically appropriate time frame for each patient, they met guideline standards for 75 patients (Figure 1)—eight of the patients experiencing a first episode (57 percent) and 67 of the patients with multiple episodes (78 percent). Patients for whom physicians indicated time frames that were too short (25 percent) had fewer previous hospitalizations (χ2=23.8, df=5, p<.001) and higher CGI scores for negative symptoms (Mann-Whitney, z=-2.01, p=.044).

When asked what they actually told their patients about the appropriate duration of maintenance therapy, physicians stated that in 26 cases they had not (yet) discussed relapse prevention with their patients at all, and that in another 26 cases they had not discussed a clear time frame. Psychiatrists gave correct recommendations for relapse prevention to only 33 patients and recommended time frames that were too short for the remaining 15 patients.

The amount of information that actually reached the patients was less than the physicians indicated. When the patients were asked about what their physicians told them about maintenance therapy (N=92), 71 (77 percent) stated that their physicians had never discussed this topic or had not mentioned a clear time frame. Eleven patients (12 percent) mentioned time frames that were too short, and only ten patients (11 percent) displayed accurate knowledge of the optimal duration of antipsychotic relapse prevention.

Only four patients planned to discontinue medication immediately after being discharged. Eighteen patients (20 percent) intended to continue with medication for less than one year, nine patients (10 percent) for one to three years, and 20 patients (22 percent) for at least four years. A total of 41 patients (45 percent) did not know for how long they should take medication or specified no clear time frame.

Physicians considered nonadherence before admission as a problem for 51 of the documented patients. They stated that for 78 patients they had taken some measure to improve adherence. However, when physicians were questioned about three key interventions for improving adherence, it was revealed that only 30 patients had received psychoeducation (structured group or single session) and only 16 were prescribed a depot preparation. For only 24 patients did the physician contact the physician who would be responsible for the patient after discharge. Overall, 55 of the patients had received any of these interventions. Patients who were receiving psychoeducation were younger (Mann-Whitney z=-2.33, p=.02) and had a shorter duration of illness (Mann-Whitney z=-2.10, p=.04) and fewer hospitalizations (χ2=11.76, df=5, p=.04) than patients who were not receiving psychoeducation. No significant associations between patient characteristics and prescription of depot antipsychotics or contacting the outpatient physician were found.

Discussion

Our results suggest that physicians' awareness of the optimal duration of maintenance therapy has increased since the studies performed ten years ago, which had shown that up to 90 percent of physicians indicate a duration of therapy for their patients that is too short.

It is astonishing that, despite good theoretical knowledge about relapse prevention, the psychiatrists in this study did not give clear recommendations to their patients. It is difficult to explain why psychiatrists advised only 33 percent of their patients of the therapeutic standard for long-term treatment for schizophrenia. From the physicians' point of view, one deterrent to better communication might be the assumption that patients would have rejected maintenance therapy or would have been shocked by the information they received. In addition, they might have assumed that the follow-up physicians would discuss this issue with the patients.

However, neglecting to communicate with patients for whatever reason seems especially inappropriate in view of results from studies on physician-patient communication that show that effective communication—for example, discussion of management plans—improves health outcomes (7). New structured models of patient participation—for example, shared decision making (8)—might be helpful in this context.

Another reason for the lack of communication might be that psychiatrists estimate a more positive prognosis for their own patients than they would for "the average patient." However, there is little evidence to support the predictability of relapse among persons with schizophrenia (9).

Nonadherence was seen as a problem for many of the patients in this study, but little was done to improve adherence. Psychoeducation was offered to only 30 percent of the patients, which might have been justified if resources were limited. Depot formulations were prescribed for only 16 percent of patients. Depot risperidone had just been launched at the time of the interviews; thus the incompatibility of classical compounds might still have been a deterrent to prescribing depot medications. In our view, there is also no satisfactory explanation for why the assigned follow-up physicians were not contacted routinely, which might have helped smooth patients' transition to outpatient care (10).

In our survey we studied real patients instead of using case vignettes. The care provided by the 50 physicians in eight hospitals represents the actual status of care for inpatients with schizophrenia in the region studied, although the sample might have been skewed toward more motivated psychiatrists. Patients were selected according to diagnosis and time of discharge only, so the study population was fairly representative of naturalistic conditions.

To assess the amount of information provided by physicians, we interviewed both physicians and patients in this study. This approach meant that we could not define a benchmark for information, because the statements of patients and physicians diverge. However, we believe that the most important finding—that physicians themselves reported not providing information to their patients—is to be considered valid, given that psychiatrists' statements would be expected to be biased toward more social desirability.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that psychiatrists have acceptable knowledge of the optimal duration of antipsychotic maintenance therapy but fail to give clear recommendations to their patients and do not routinely use adherence-enhancing strategies. Likewise, patients' knowledge of antipsychotic maintenance therapy is poor.

The authors are affiliated with the psychiatry department of Technische Universität München in Munich, Germany. Send correspondence to Dr. Hamann at Klinik und Poliklinik für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie der Technischen Universität München, Möhlstra?e 26, 81675 München, Germany (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Extent of agreement between guidelines on relapse prevention for patients with schizophrenia and actual practice

1. Gilbert PL, Harris MJ, McAdams LA, et al: Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients: a review of the literature. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:173–188,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kissling W: Compliance, quality assurance, and standards for relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 382:16–24,1994Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Meise U, Kurz M, Fleischhacker WW: Antipsychotic maintenance treatment of schizophrenia patients: is there a consensus? Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:215–225,1994Google Scholar

4. 2-CGI: Clinical Global Impressions, in Manual for the ECDEU Assessment Battery. Edited by Guy W, Bonato RR. Chevy Chase, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1970Google Scholar

5. Bäuml J, Kissling W, Pitschel-Walz G: [Psychoeducative group therapy for patients with schizophrenia: influence on knowledge and compliance.] [In German] Nervenheilkunde 15:145–150,1996Google Scholar

6. [DGPPN Treatment Guideline for Schizophrenia.] [In German] Darmstadt, Steinkopff Verlag, 1998Google Scholar

7. Stewart MA: Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Canadian Medical Association Journal 152:1423–1433,1995Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hamann J, Leucht S, Kissling W: Shared decision making in psychiatry. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 107:403–409,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al: Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:241–247,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Boyer CA, et al: Linking inpatients with schizophrenia to outpatient care. Psychiatric Services 49:911–917,1998Link, Google Scholar