Brief Reports: The Fidelity of Supported Employment Implementation in Canada and the United States

Abstract

Supported employment has been documented in the United States as an evidence-based practice that helps people with severe mental illness obtain and maintain employment. The evidence is strongest for the programs that follow the individual placement and support model. This brief report examines the degree to which supported employment programs in British Columbia, Canada, are similar to those in the United States. Data from the Quality of Supported Employment Implementation Scale were compiled in 2003 for ten supported employment programs from vocational agencies in British Columbia and were compared with data from 106 supported employment programs and 38 non-supported employment programs in the United States. Overall, the Canadian supported employment programs that followed the individual placement and support model had the highest fidelity.

Supported employment has been identified as an evidence-based practice that assists people with severe mental illness obtain and maintain work (1,2). A meta-analysis of methodologically sound quasi-experimental studies and randomized controlled trials that investigated the vocational rehabilitation of people with severe mental illness demonstrated that supported employment programs were more effective than traditional vocational services (3). Other reviews have reached similar conclusions (1,4).

The goals of supported employment have been outlined by Bond and colleagues (2) as follows: "Supported employment programs typically provide individual placements in competitive employment—that is, community jobs paying at least minimum wage that any person can apply for—in accord with client choices and capabilities, without requiring extended prevocational training…. They actively facilitate job acquisition, often sending staff to accompany clients on interviews, and they provide ongoing support once the client is employed."

Individual placement and support is the standardized supported employment model for people with severe mental illness. The individual placement and support model includes several principles: eligibility is based on consumer choice, supported employment is integrated with mental health treatment, attention is focused on consumer preferences, competitive employment is the goal, the job search is rapid from the start, and follow-along supports are continuous and time unlimited (5). Of the existing supported employment models, the individual placement and support model is described by many authors as the most effective approach to helping people with severe mental disorders obtain and maintain a job (3,6).

Interest in implementing and evaluating supported employment programs that adhere to the above-mentioned principles has spread from the United States to several areas, such as the United Kingdom (7), Finland (8), Germany (9), other European countries (10), Japan (11), Hong Kong (12), and Canada, specifically Montreal (13) and Vancouver (14). However, almost every published randomized controlled trial on supported employment programs has been conducted exclusively in the United States (3,4); only one recent randomized controlled trial of individual placement and support was conducted in Québec (13). Accordingly, the feasibility of implementing the American model of supported employment outside the United States has not yet been adequately documented in the literature.

As an evidence-based practice gains popularity, it is crucial to have a method for identifying programs that are implementing it according to its key principles. This need has given rise to the development of fidelity scales, which are defined as instruments that measure the degree of implementation of a practice (15). Fidelity scales have many uses in practice and research. These scales provide documentation of the dissemination of a defined practice; offer operational guidelines to agencies seeking to implement a new practice; identify standards by which programs may monitor their progress; offer criteria for state agencies (for example, mental health and vocational rehabilitation) to assess multisite projects, reward high performers, and identify outliers needing technical assistance; and provide a tool for consumers and family members who make service choices and advocate for better services. The utility of fidelity scales is indicated by studies suggesting that programs that implement evidence-based practices with high fidelity generally have better outcomes (16).

Because of the differences in national health care systems and labor conditions, it was unclear whether the Canadian supported employment programs would achieve high fidelity to such programs in the United States. Consequently, the purpose of this study was to compare the implementation of Canadian supported employment programs with the implementation of such programs in the United States and to contrast these supported employment programs with non-supported employment programs in the United States.

Methods

The coordinators of five vocational agencies that offered supported employment programs in the greater Vancouver area were contacted to determine whether their programs corresponded to Bond and colleagues' (2) definition of supported employment. All five agencies agreed to participate in the study. Altogether, ten vocational programs operated by the five agencies met the screening criteria for providing supported employment. The ten supported employment programs were separated into two groups according to whether or not the program followed the individual placement and support model. An individual placement and support model was followed by two programs from the Canadian Mental Health Association in Vancouver and Burnaby and three programs from the Fraser Health Authority. The remaining five programs did not follow such a model (that is, supported employment programs were located in a comprehensive rehabilitation center that offered other services, such as housing and skills training): two program from the Coast Foundation Society, two programs from Gastown Vocational Services, and one program from the British Columbia Society of Training for Health and Employment Opportunities.

Interviews were conducted in 2003 with the program coordinator and one or more employment specialists from each of the agencies. They were interviewed by one interviewer and two raters, who evaluated the programs' implementation of the supported employment program with the Quality of Supported Employment Implementation Scale (QSEIS) (17). Each interview lasted 2.5 hours on average.

In order to compare the Canadian supported employment programs with vocational programs in the United States, we used two comparison samples from a U.S. study of QSEIS (18), which involved a telephone survey with directors of 106 supported employment programs and 38 vocational programs that offered other types of vocational services. This sample was drawn from an opportunity sample from five states. The non-supported employment programs included prevocational programs, enclaves, clubhouses, affirmative businesses, and a variety of other programs (18).

The QSEIS consists of 35 items, each rated on a 5-point behaviorally anchored response scale; a rating of 5 indicates full implementation, 4 indicates moderate fidelity, and the remaining scale points indicate increasingly larger departures from supported employment standards. On the basis of factor analysis, Bond and colleagues (18) defined five QSEIS subscales: job placement (seven items), integration with mental health treatment (four items), long-term support (five items), teamwork (four items), and engagement (four items).

Results

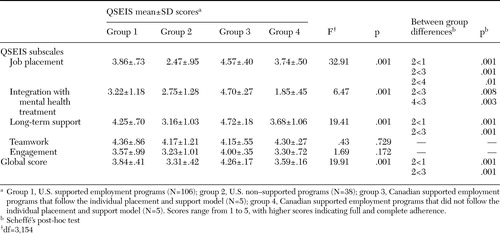

As shown in Table 1, the multivariate analysis of variance showed significant differences between all four groups (two from Canada and two from the United States) on three subscales and the global score from the QSEIS. The tests of between-subjects effects yielded significant F values for job placement, integration with mental health treatment, long-term support, and the QSEIS global score. Scheffé's post-hoc test yielded three significant differences. First, both of the Canadian supported employment groups and the U.S. supported employment group were rated significantly higher on the job placement subscale than the non-supported employment comparison sample in the United States. Second, Canadian supported employment programs that followed the individual placement and support model scored significantly higher on the integration for the mental health treatment subscale than Canadian supported employment programs that did not follow the individual placement and support model and non-supported employment programs in the United States.

Third, with respect to the long-term subscale and the QSEIS global score, Canadian supported employment programs that followed the individual placement and support model and U.S. supported employment programs scored significantly higher than U.S. non-supported employment programs.

Discussion and conclusions

The main objective of this study was to examine QSEIS factors to compare the implementation of Canadian supported employment programs with the implementation of such programs in the United States and to contrast these supported employment programs with non-supported employment programs in the United States.

The Canadian supported employment programs that followed the individual placement and support model scored significantly higher on three out of five QSEIS subscales and the global score than non-supported employment programs offered in the United States.

With respect to the job placement subscale, all supported employment programs from Canada and the United States attained a higher score than non-supported employment programs in the United States. The items on the QSEIS concerning the focus on supported employment compared with other services and the possibility to offer prevocational activities to clients made a clear distinction between supported employment programs and non-supported employment programs.

Supported employment programs that followed the individual placement and support model obtained the highest score in terms of the integration with mental health treatment subscale, when compared with supported employment and non-supported employment programs in the United States and Canadian supported employment programs that did not follow the individual placement and support model. As observed previously (18), the main difference between the broad definition of a supported employment program and the individual placement and support model is the integration of mental health treatment. Consequently, the results of this study validated the higher scores obtained from the individual placement and support model, in contrast with other types of supported employment programs.

With regard to long-term support, non-supported employment programs in the United States and Canadian supported employment programs that did not follow the individual placement and support model presented the lowest scores. In the latter Canadian programs, continuous support is not offered to consumers after job placement. Consequently, the duration of support is minimal after participants obtain employment. Given the relationship between long-term support and job tenure (19), this weakness in the Canadian programs that did not follow the individual placement and support model is a concern. Also, compared with supported employment and non-supported employment programs in the United States and Canadian supported employment programs that did not follow the individual placement and support model, Canadian supported employment programs that followed the individual placement and support model presented the highest scores in terms of fidelity of supported employment program implementation—scores that indicated close to complete implementation of supported employment standards.

Overall, this study showed that the implementation of Canadian supported employment programs, regardless of whether the program followed the individual placement and support model, does not differ significantly from that of U.S. supported employment programs. However, Canadian supported employment programs differed substantially from non-supported employment programs in the United States. Myriad adaptations of the supported employment model exist so that the supported employment program can fit a particular agency's philosophy. This philosophy often stems from the integration with other services already offered in the agency and how they are funded.

The main limitation of this study was the limited geographic inclusion of the Canadian sample, which consisted of only five British Columbian vocational agencies. It would be beneficial to expand the comparisons to other vocational agencies in Canada.

Furthermore, our results were based solely on interviews, and we did not use other means of gathering information, such as systematic visits of each program or consultation of documents from each Canadian site participating in this study. Therefore, the validity of the interview results may be limited. In fact, Bond and colleagues (20) recommend that multiple sources of information be used for valid ratings.

Another limitation concerns the absence of association between the components of supported employment offered in each agency and vocational outcomes (17). It is important to determine which components of the supported employment programs implemented in Canada are related to vocational outcomes and which could be adapted, modified, omitted, or added without affecting outcomes. Accordingly, some questions are left unanswered: What are the most significant components of supported employment in Canada? Is there any other strong empirical evidence that might be useful to consider in the implementation of supported employment programs? Additionally, sociopolitical issues about the implementation of supported employment programs in Canada have to be taken into consideration when investigating the vocational successes of people with severe mental illness. For instance, the acquisition of competitive employment could become a disincentive for people with severe mental illness, because people can lose their medical benefits after two consecutive years in competitive employment and they can lose financial support if they work full-time (21). The existence of a socialized health care system in Canada does not appear to have facilitated the proliferation or uptake of supported employment services, because these remain few in number.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation grant. The authors thank Leigh Thomson and Huguette Lind from the individual placement and support program of the Vancouver/Burnaby Canadian Mental Health Association; Cathy Johnson, Garry Bona, and Isla Patterson from the participation, action, counseling, and training employment services of the Coast Foundation Society; Allison Luke, Reta Derkson, and Kathy Elliot, from the supported employment services of Fraser Health Authority; Anne McLeod, Jane O'Connor, and Mariella Bozzer from the supported employment program of Gastown Vocational Services; Joe Hoffman, Mike Broderick, and Terri Costello from the supported employment program of the British Columbia Society of Training for Health and Employment Opportunities; and Kim Calsaferri from Vancouver Coastal Health.

Dr. Corbière is affiliated with the Institute of Health Promotion Research, Dr. Goldner with the department of psychiatry, and Ms. Ptasinski with the department of occupational therapy at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Dr. Bond is with the department of psychology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. Send correspondence to Dr. Corbière at the University of British Columbia, LPC Building, 2206 East Mall, Room 414, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 1Z3 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Multivariate analysis of variance of comparisons between vocational programs in Canada and the United States on the Quality of Supported Employment Implementation Scale (QSEIS)

1. Bond GR: Supported employment: evidence for an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:345–359,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313–322,2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Crowther RE, Marshall M, Bond GR, et al: Helping people with severe mental illness to obtain work: systematic review. British Medical Journal 322:204–208,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Twamley EW, Jeste DV, Lehman AF: Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:515–523,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Drake RE, Becker DR, Clark RE, et al: Research on the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Psychiatric Quarterly 70:289–301,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bustillo JR, Lauriello J, Horan WP, et al: The psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia: an update. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:163–175,2001Link, Google Scholar

7. Rinaldi M, McNeil K, Firn M, et al: What are the benefits of evidence-based supported employment for patients with first-episode psychosis? Psychiatric Bulletin 28:281–284,2004Google Scholar

8. Saloviita L, Pirtimaa R: The introduction of supported employment in Finland. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 23:145–147,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Reker T, Eikelmann B: Predictors of success in supported employment programmes: results of a prospective study. Psychiatrische Praxis 26:218–223,1999Medline, Google Scholar

10. Jenaro C, Mank D, Bottomley J, et al: Supported employment in the international context: an analysis of processes and outcomes. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 17:5–21,2002Google Scholar

11. Fuller TR, Oka M, Otsuka K, et al: A hybrid supported employment program for persons with schizophrenia in Japan. Psychiatric Services 51:864–866,2000Link, Google Scholar

12. Wong K, Chiu LP, Tang SW, et al: Vocational outcomes of individuals with psychiatric disabilities participating in a supported competitive employment program. Work 14:247–255,2000Medline, Google Scholar

13. Latimer E, Becker D, Drake RE, et al: Generalizability of the IPS model of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: results and economic implications of a randomized trial in Montreal, Canada. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 8(suppl 1): S29, 2005Google Scholar

14. Thomson L, Oldman J: Working Towards Wellness: An Evaluation Report From a Two-Year Supported Employment Redesign Project. British Columbia, Canadian Mental Health Association, 2003Google Scholar

15. Mowbray CT, Holter MC, Teague GB, et al: Fidelity criteria: development, measurement, and validation. American Journal of Evaluation 24:315–340,2003Crossref, Google Scholar

16. McGrew J, Griss M: Concurrent and predictive validity of two scales to assess the fidelity of implementation of supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 29:41–47,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Bond GR, Picone J, Mauer B, et al: The quality of supported employment implementation scale. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 14:201–212,2000Google Scholar

18. Bond GR, Evans LJ, Gervey R, et al: A Scale to measure the quality of supported employment for persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 17:1–12,2002Google Scholar

19. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Becker DR: The durability of supported employment effects. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:55–61,1998Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: A fidelity scale for the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 40:265–284,1997Google Scholar

21. Corbière M, Mercier C, Lesage AD, et al: L'insertion au travail de personnes souffrant d'une maladie mentale: analyse des caractéristiques de la personne. [Work integration of people with a mental illness: analyzing individual characteristics.] Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar