Fidelity of an Outreach Treatment Program for Chronic Crack Abusers in the Netherlands to the ACT Model

Abstract

This study evaluated an effective outreach treatment program in the Netherlands for chronic, high-risk crack abusers on its adherence to the assertive community treatment model. Fidelity was tested on 25 criteria of the Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Scale. Adherence was high on several factors: a small caseload, staff capacity, a nurse and a substance abuse specialist on staff, explicit admission criteria, low intake rate, and intensity of service. Future programs that focus on treating crack addiction should implement these components. The outreach treatment program showed low adherence to the assertive community treatment model for including a psychiatrist and a vocational specialist, both of which are important factors that should be implemented in future programs. Other factors were observed to be important for treating this population: a strong focus on the client-therapist relationship, stagewise substance abuse treatment, and on-the-spot incentives to keep this population involved in treatment.

From February 2000 to December 2001 the Bouman addiction care service, located in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, conducted a randomized controlled trial to investigate the effects of an innovative program that was specifically tailored to treat chronic, high-risk crack abusers who were insufficiently engaged in standard addiction treatment services. Strong emphasis was placed on getting in touch with these persons and motivating them for treatment. The program consisted of assertive outreach, a time-out service, case management, and adjunctive services that were used as incentives—for example, acupuncture treatments and a day program with free meals and with bath and bed facilities. Strong emphasis was placed on the client-therapist relationship; a relationship built on trust, understanding, and education was considered to be important. Patients in the outreach treatment program received the services of the program along with standard addiction care. Patients in this program were compared with patients in a control group who received standard addiction care alone. Outcome measures included treatment compliance, improvement in various life areas, and satisfaction.

A process evaluation provided insight into the clients' opinions about the outreach treatment program. The study showed that patients in the outreach treatment program had better compliance and higher treatment satisfaction than patients who received standard care only (1). These results were positive, considering the poor engagement rates often reported in treatment for cocaine-dependent individuals. There were also indications for a better outcome for the treatment group in physical health, general living conditions, and psychiatric status, but these effects needed further investigation.

Although the pioneering outreach treatment program showed several advantages over standard addiction care, it was a first attempt to develop an effective treatment for seriously impaired crack abusers. Replication of the study was needed to verify the positive results. Furthermore, it was not clear to what extent the outreach treatment program was in agreement with other forms of community treatment. Thus, in our efforts to ground theory for an evidence-based practice for this relatively treatment-resistant population, comparison with a similar evidence-based treatment was necessary. To this end the assertive community treatment model was chosen as a point of reference. Making a comparison between assertive community treatment and the outreach treatment program is useful because both treatment modalities serve many persons with co-occurring chronic psychiatric and substance use disorders. Also beneficial is the availability of a valid tool to assess program fidelity to assertive community treatment: the Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Scale (DACTS), which measures adherence to critical elements of assertive community treatment (2).

The study presented here examined similarities and differences between assertive community treatment and the outreach treatment program according to criteria defined in the DACTS. The main aim of this study was to ground theory for an evidence-based intervention for crack addiction. Also, there is a need to develop crack-related treatments that are based on the critical ingredients that were found to be effective in this study. These treatments need to be standardized (that is, implemented in a fidelity scale); this study made the first attempt to standardize these critical elements. Considerations about implementing effective components of the program of elements in future treatment planning for chronic, high-risk crack abusers are discussed.

Methods

This study used the existing data of the randomized controlled trial (1). Fidelity assessment took place two years after the closure of the outreach treatment program. All analyses were based on well-documented data collected during the study period, from February 2000 to June 2001. During this period 63 patients entered the outreach treatment program and followed the program for a maximum of eight months.

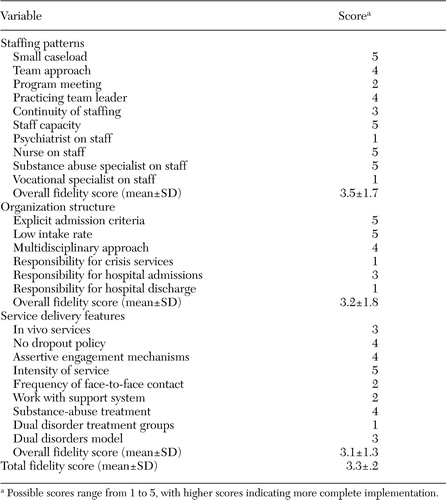

The fidelity assessment was done by the first author according to the DACTS manual (2). The DACTS is a validated 28-item scale that measures model fidelity across a wide range of observable criteria (3). In this scale three dimensions are distinguished: staffing patterns, organization structure, and service delivery features. The degree to which critical items of assertive community treatment were implemented in the outreach treatment program was rated with a scale, based on the mean score of all items. Possible DACTS scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more complete implementation.

In this study 25 of the 28 criteria for adherence to the assertive community treatment model were derived from four sources: an interview with the former team leader and case manager of the outreach treatment program, computerized registration data of contacts, randomly selected clinical records, and management information, including a treatment manual. In accordance with international studies, two of the DACTS items—program size and role of consumers on the team—were not included in the analysis, because these items were added after the psychometric tests were conducted. The item time-unlimited service was excluded because of the fixed time associated with our randomized controlled trial.

Analyses were conducted by using SPSS for Windows 11.0, standard version. Descriptive statistics were generated to evaluate adherence to assertive community treatment on each of the examined items. Implementation scores were rated by means or medians.

Results

Table 1 presents data on the outpatient treatment program's adherence to each of the dimensions of the DACTS. Overall, the program's DACTS score revealed a moderate implementation of the assertive community treatment model (mean score of 3.3). Adherence to staffing patterns was highest (mean score of 3.5), followed by adherence to organization structure (mean score of 3.2), and service delivery features (mean score of 3.1).

The items of highest fidelity (score of 5) included a small caseload, staff capacity, a nurse on staff, a substance abuse specialist on staff, explicit admission criteria, a low intake rate, and intensity of service. Data from the digital information system showed a mean caseload ratio of 5:1 during the 16-month period. A calculation based on management information led to a staff capacity of 96.3 percent. The outpatient treatment program had a ratio of 2.4 full-time nurses for every 100 patients. Except for one individual, all staff members (excluding administrative workers) had at least one year of clinical experience with substance abuse treatment. Because the program originally formed the experimental condition of a randomized controlled trial, explicit admission criteria were formulated to include the target group. In the treatment protocol a phased enrollment of patients was proposed to control the admission process and to ensure a stable treatment environment. Contact registrations showed an average enrollment of 3.7 new patients per month. The selected clinical records revealed that the median amount of time that a staff member spent per week on face-to-face contacts was 126 minutes.

The items of lowest fidelity (score of 1) included a psychiatrist on staff, a vocational specialist on staff, responsibility for crisis services, responsibility for hospital discharge, and dual disorder treatment groups. Management data revealed that neither a psychiatrist nor a vocational specialist was represented on the outreach treatment program team. Staff members were not authorized to initiate crisis services and hospital discharges. Finally, the program lacked specific dual disorder treatment groups.

Discussion

This study compared an effective outreach treatment program for chronic, high-risk crack abusers with an evidence-based community care model—that is, assertive community treatment. Adherence to assertive community treatment was measured by the DACTS. The study examined similarities and differences between the outreach treatment program and assertive community treatment according to criteria defined in the DACTS.

In agreement with assertive community treatment, the outreach treatment program used explicit inclusion criteria and created a stable treatment environment by means of a low intake rate. Given the high levels of symptoms and deterioration among patients in the outreach treatment program, a small caseload and a high intensity of service were provided. Furthermore, continuity of staffing was guaranteed, and nurses and substance abuse professionals were part of the team. Because both the outreach treatment program and assertive community treatment attached great importance to the above-mentioned treatment characteristics, we recommend that they be included in future program planning for chronic, high-risk crack abusers. According to assertive community treatment standards, a vocational specialist needs to be included as well, because studies have clearly demonstrated the efficacy of supported employment (4).

In the outreach treatment program the absence of a psychiatrist and dual disorder treatment groups was problematic, considering that dual diagnosis was a common feature among the patients. Although the management of the outreach treatment program acknowledged the importance of a psychiatrist on the staff, financial cutbacks did not permit the inclusion of one. However, the lack of a dual disorder treatment group was a well-considered choice: in our pilot study, group therapy was associated with high levels of dropout, and we therefore assumed that this treatment modality was not feasible for chronic, high-risk crack abusers.

Although high fidelity to the assertive community treatment model is recommended to achieve good outcomes, it has been argued that models cannot simply be transferred to other sites or patient groups without adaptation (5). Instead of falling prey to the "single model trap" (6), it is important to address cultural and other local circumstances (7,8). Therefore, we hypothesize that in the case of chronic, high-risk crack abusers, the special arrangements described below are necessary to engage and retain this difficult-to-reach population in treatment.

First, our study indicated that forming a trusting relationship is of great importance. We strongly believe that assertive community treatment's goal of ensuring that patients have contact with multiple team members at the same time is counterproductive in our target population. In our opinion, the individualized client-therapist relationship is very important, because this particular patient group of seriously impaired addicts has difficulties forming a trusting relationship. Conventional counseling techniques based on confrontation and abstinence should be replaced by stagewise substance abuse treatment geared to education, harm reduction, and increasing motivation (9,10).

Second, we consider the intensity of at least four face-to-face contacts per week, as proposed in assertive community treatment, to be too much for chronic, high-risk crack abusers. It is possible that this so-called "high pampering" has a reverse effect on their treatment compliance.

Third, on-the-spot incentives—that is, services that patients consider to be important, such as free meals and acupuncture treatments—should be directly available in the program. The choice of these incentives depends a great deal on local circumstances and patients' service needs and must serve no goal other than to keep the target group involved in treatment.

Conclusions

Evidence-based practice for chronic crack addiction has been lacking; therefore, this study is of great practical relevance. There is a need to develop outreach treatment programs based on the elements that were found to be effective in this study, as well as a fidelity scale for this type of program. Further research is needed to study the effects of modified high-fidelity programs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by ZonMw, the Dutch Organization for Health Care Research and Development in the Hague, the Netherlands.

Dr. Henskens is affiliated with the Municipal Health Service of Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Dr. Mulder is with the mental health group Europoort and with Erasmus MC, both in Rotterdam. Dr. Garretsen and Dr. Bongers are affiliated with the Tranzo Research Centre at the University of Tilburg and with the Addiction Research Institutes at the Universities of Rotterdam, Maastricht, Tilburg, and Nijmegen in the Netherlands. Dr. Kroon is with the reintegration research unit at the Trimbos Institute of Utrecht in the Netherlands. Send correspondence to Dr. Henskens at the Municipal Health Service, Department of Individual-Bound Care, P.O. Box 70032, 3000 LP Rotterdam, the Netherlands (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Adherence to items on the Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Scale by an outreach treatment program that was tailored to treat chronic, high-risk crack abusers in the Netherlands

1. Henskens R, Garretsen H, Bongers I, et al: Effectiveness of an outreach treatment program for inner city crack abusers: compliance, outcome, and client satisfaction. Substance Use and Misuse, in pressGoogle Scholar

2. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:217–232,1998Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Salyers MP, Bond GR, Teague GB, et al: Is it ACT yet? Real-world examples of evaluating the degree of implementation for assertive community treatment. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:304–320,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Crowther R, Marshall M, Bond G, et al: Vocational Rehabilitation for People With Severe Mental Illness, 1st ed. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2004Google Scholar

5. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Teague GB, et al: Fidelity to assertive community treatment and client outcomes in the New Hampshire dual disorders study. Psychiatric Services 50:818–824,1999Link, Google Scholar

6. Bond GR, Evans L, Salyers MP, et al: Measurement of fidelity in psychiatric rehabilitation. Mental Health Services Research 2:75–86,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, et al: Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:469–476,2001Link, Google Scholar

8. Paulson RI, Post RL, Herinckx HA, et al: Beyond components: using fidelity scales to measure and assure choice in program implementation and quality assurance. Community Mental Health Journal 38:119–128,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Minkoff K: An integrated treatment model for dual diagnosis of psychosis and addiction. Hospital Community Psychiatry 40:1031–1036,1998Google Scholar

10. Drake RE, Mueser KT: Psychosocial approaches to dual diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:105–118,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar