Gender Identity and Implications for Recovery Among Men and Women With Schizophrenia

Abstract

The concept of gender considers masculinity and femininity as a cultural construct that varies along a continuum. Subjectively perceived, gender may affect the experience of illness among persons with schizophrenia and may have an impact on treatment and recovery. This study evaluated gender identity, according to the Bem Sex Role Inventory, among 90 men and women with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. The findings indicate that persons with schizophrenia experience their gender identity in ways that vary from culturally normative standards. Both men and women scored lower on traditional masculine descriptive measures compared with persons without schizophrenia. This finding has important implications for recovery.

A wealth of research has been conducted on sex differences among persons with schizophrenia, with sex differences based on the dichotomous variables "male" and "female" (1). The results of this research suggest that women who have schizophrenia may have a better global outcome than men, as manifested by differences in use of health care resources and recovery, such as better course of hospital treatment and a smaller likelihood of relapse after hospital discharge.

Deaux (2) defined sex comparisons as based on demographic categories of male and female, whereas gender comparisons involve cultural issues concerning the nature of femaleness and maleness, or of masculinity and femininity. Lewine (3) suggested that this terminology should be used in the study of schizophrenia. The demographic construct of sex does not take into account how gender may be a matter of cultural orientation. Nor does it take into account how psychological gender, as a matter of self-perception, may affect the experience of illness among men and women who have schizophrenia and how this may have an impact on treatment and recovery (4).

Studies that evaluate only sex differences offer few clues as to how recovery interventions might be customized for men and women with schizophrenia. Nasser and associates (4) recently noted the critical need for future research initiatives in schizophrenia that expand beyond a dichotomous comparison of male and female differences.

Cultural expectations for men and women with schizophrenia may differ, and it has been reported that men with schizophrenia may be less able to carry out normative gender role activities than their female counterparts (4). A limited body of literature on gender identity and schizophrenia suggests that men and women with schizophrenia may experience disturbed sex role identification (5). Perhaps in relation to deep and pervasive stigmatization of mental illness, men and women with schizophrenia often appear "genderless" insofar as mental illness itself is perceived to eclipse other factors in identity.

In the study reported here we evaluated gender identity among men and women with schizophrenia by characterizing level of self-identification with traditionally masculine and traditionally feminine role concepts. We hypothesized that gender identity among persons with schizophrenia is likely to differ from normative gendered orientations among men and women. Specifically, we hypothesized that men with schizophrenia would have less identification with characteristics associated with male gender than would men who did not have schizophrenia.

Methods

The study was part of a research project titled Subjective Experience and the Culture of Recovery with Atypical Antipsychotics (SEACORA), an anthropologic investigation, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, of 90 persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, all of whom were taking second-generation antipsychotic medications. The study was conducted between September 1999 and June 2002.

The selection criteria included a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to clinical research criteria, age of 18 to 55 years, at least two years since the first psychotic symptoms, at least six months of treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic drug, absence of comorbid substance abuse or organic impairment, and sufficient clinical stability to provide informed consent and participate in interviews.

The subjective experience of schizophrenia was studied though use of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), the Brief Psychiatric Ratings Scale (BPRS) for symptom severity, ethnographic interviewing and observations, and administered questionnaires.

Gender identity was evaluated with the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI) (6). The BSRI consists of 60 self-rated personality-related items empirically identified by Bem as associated with Euro-American gender stereotypes—for example, "independent" and "yielding." Ratings are made on a scale ranging from 1, never or almost never true of oneself, to 7, always or almost always true of oneself. The theoretical assumption of this widely used inventory is that both men and women have masculine and feminine gender attributes. Nevertheless, use of the BSRI has produced norms for gender role identifications for men and for women (6). Both the average woman's and the average man's masculine and feminine scores are expected to approximate 50 on both scales. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) approach to repeated measures was used to compare mean scores on the masculine and feminine role scales for men and women and for the two study sites—two community mental health outpatient facilities in a metropolitan area of the United States. The study was approved by the local institutional review board.

Results

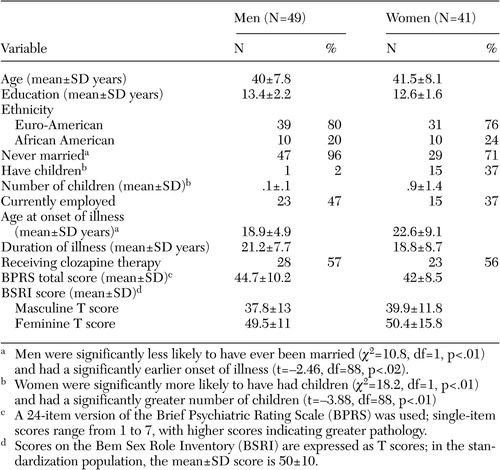

Selected clinical and demographic variables of men and women in the study group are listed in Table 1. Current medications included clozapine (57 percent of participants), risperidone (18 percent), olanzapine (17 percent), and quetiapine (7 percent). No significant differences were noted between men and women in age, duration of illness, total BPRS score, or proportionate use of clozapine. The men had an earlier age at onset of schizophrenia and were less likely to have ever been married compared with women. The women in the sample were more likely to have had children compared with men.

MANOVA analysis indicated that the differences between men and women on the BSRI were not statistically significant—that is, the average scores of men and women were not different from each other on either the masculine or feminine role scales. Both men and women had scores on the feminine role scale at the normative average for their sex (49.54 and 50.44, respectively). On the other hand, both the average score of men (mean±SD=37.39±12.95, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=33.66 to 41.91) and of women (mean±SD= 39.85±11.8, CI=35.62 to 44.08) were below the normative value of 50 for the masculine role scale (t=5.81, df=37, p<.001 and t=4.71, df=29, p<.001, respectively). Both sexes endorsed traditionally male sex role statements to a lower extent than normative expectations for their respective sex.

Discussion

Our hypothesis was confirmed in that men and women with schizophrenia were observed to experience gender identity that differed from normed standards. Despite novel pharmacologic treatments that promise better clinical outcomes, treatment systems that have been implemented in community settings, and prominent antistigma campaigns, this finding seems to be consistent with reports published before the advent of second-generation antipsychotics (7). Our second hypothesis—that men with schizophrenia would have less identification with traditional male gender role characteristics—was also confirmed. However, this finding was also observed for women with schizophrenia.

Both the men and the women in our sample had lower scores on traditional masculine personality descriptive characteristics. This finding has potentially important implications for gender identity and gender role, factors that are key contributors to an individual's experience of schizophrenia and that are critical in the recovery process. Although our study was limited by its relatively small sample, lack of longitudinal assessment, and the fact that the BSRI may not completely identify self-view dimensions of individuals of all cultural backgrounds, some preliminary conclusions may be proposed.

Gender identity is the subjective experience of one's individuality as male or female, and the painful effects of schizophrenia on gender identity are seen among both men and women. The onset of schizophrenia typically occurs during late adolescence or young adulthood, coinciding with the period during which multiple levels of identity development normally occur. Because men may often develop the illness earlier in life, compared with women, effects on gender identity among men with schizophrenia may be more profound than those among women.

LaTorre (5) suggested that men in Western society have a more aggressive role imposed on them than men in other societies and that this may contribute to uncertainty about gender identity among adolescent males; however, this work is largely suppositional (4). The results of our study are consistent with the notion that schizophrenia is associated with disturbance of gender identity and that the overall effect is to diminish masculine-associated identity traits among both men and women.

Gender role is the public expression of one's individuality as male or female. Notman and Nadelson (8) describe gender role as "a culturally constructed concept referring to the expectations, attitudes, and behaviors that are considered to be appropriate for each gender in that particular culture." Although persons with schizophrenia frequently experience severe deficits in vocational and interpersonal functioning, such deficits may have particularly significant gender role implications for men, who may have fewer options as to their gender role, which centers primarily around employment—than women, whose options include not only employment but also assumption of a role as a mother or household manager. In our study, the women with schizophrenia were more likely to marry than their male counterparts and also had more children than the men.

Recovery efforts must address not only effects of symptoms on functional status but also the internal state of the individual with regard to self-expectations and self-esteem. Page (9) suggested that family members may have different expectations for men with schizophrenia than for women with schizophrenia. Seeman (10) noted that expected educational and other achievements may be less reasonable for men than for women.

It is critical that individual and family-oriented interventions address the issue of psychosocial and vocational goals in a realistic manner and that issues of gender role and self-esteem be taken into consideration in the treatment of persons with schizophrenia. Such an approach is likely to have real effects in the recovery process on a number of fronts. For example, independence is more highly valued for men, whereas dependence on family is more sex-role-appropriate for women. Thus women may more readily accept assistance from their families, a factor that is known to be beneficial in schizophrenia outcomes. An approach that emphasizes psychosocial supports without negating individual independence and individual choice is likely to lead to improved outcomes and minimal negative effects on self-esteem. Achieving this balance is a challenge for the mental health community that requires the cooperative efforts of providers, consumers and their families.

Dr. Sajatovic is affiliated with the department of psychiatry of Case Western Reserve University, 11100 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio 44106-5000 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Jenkins is with the departments of anthropology and psychiatry, Dr. Strauss with the departments of psychology and psychiatry, and Ms. Carpenter with the department of anthropology at the university. Mr. Butt is with the Center on Outcomes Research and Education at Evanston Northwestern Healthcare in Illinois.

|

Table 1. Demographic variables, clinical characteristics, and gender identity scores among men and women with schizophrenic disorder being treated with second-generation antipsychotic medications

1. Kulkarni J: Women and schizophrenia: a review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 31:46–56, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Deux K: Sorry, wrong number: a reply to Gentile's call. Psychological Sciences 4:125–126, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Lewine RR: Sex: an imperfect maker of gender. Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:777–779, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Nasser EH, Walders N, Jenkins JH: The experience of schizophrenia: what's gender got to do with it? A critical review of the current status of research on schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28:353–362, 2002Google Scholar

5. LaTorre RA: Schizophrenia, in Sex Roles and Psychopathology. Edited by Widom DS. New York, Plenum, 1984Google Scholar

6. Bem SL: Bem Sex Role Inventory Manual. Redwood City, Calif, Mind Garden, 1978Google Scholar

7. LaTorre RA, Endman M, Gossmann I: Androgyny and need achievement in male and female psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology 32:233–235, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Notman MR, Nadelson CC: Gender, development, and psychopathology: a revised psychodynamic view, in Gender and Psychopathology. Edited by Seeman MV. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

9. Page S: On gender roles and perception of maladjustment. Canadian Psychology 28:53–59, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Seeman MV: Schizophrenic men and women require different treatment programs. Journal of Psychiatric Treatment Evaluations 5:143–148, 1983Google Scholar