Brief Reports: Symptoms of Peritraumatic and Acute Traumatic Stress Among Victims of an Industrial Disaster

Abstract

Previous studies have examined peritraumatic distress, peritraumatic dissociation, and acute stress disorder as predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The authors examined whether these three predictors were associated with PTSD symptoms when considered simultaneously. Two-hundred victims of a factory explosion in Toulouse, France, were surveyed two and six months after the event with use of retrospective self-reports of peritraumatic distress, peritraumatic dissociation, and acute stress disorder. A hierarchical multiple regression predicting PTSD symptoms six months posttrauma indicated that all three constructs explained unique variance, accounting for up to 62 percent. Peritraumatic distress and dissociation and acute stress disorder appear conceptually different from one another and show promise in identifying who is at risk of PTSD.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the context of disasters or terrorism has been found to be the most prevalent type of psychiatric morbidity (1). High levels of distress (2) and dissociation (3) at the time of the trauma, as well as symptoms of acute stress disorder (4), have been identified as robust predictors of who will develop PTSD. However, no study has yet examined the predictive power of these three constructs concurrently. We sought to examine whether these three related but different constructs would all contribute significantly to predicting PTSD symptoms in a convenience sample of disaster survivors who were surveyed by self-report in the months that followed exposure.

Methods

A factory exploded in Toulouse, France, on September 21, 2001. The blast caused 30 deaths and injured 2,242 people. Participants in the study reported here were recruited from among 892 survivors who were admitted to local emergency departments. The study's exclusion criteria were having a life-threatening injury, being mentally retarded, having a psychotic illness, or being under the age of 15 years. Five to ten weeks after the explosion, study participants were sent a questionnaire that assessed symptoms of acute stress disorder (wave 1). A total of 430 participants returned the completed questionnaire and the written informed consent form. All 430 were sent questionnaires six months after the explosion that assessed remembered peritraumatic distress and dissociation as well as current PTSD symptoms (wave 2). Peritraumatic distress is the level of distress (intense fear, helplessness, or horror) experienced during and immediately after a traumatic event. Trauma victims often report alterations in the experience of time, place, and person, called peritraumatic dissociation, which confer a sense of unreality to the event as it is occurring. A total of 188 persons dropped out.

Participants for whom more than two pieces of data were missing on each questionnaire (N=43) were excluded, yielding a sample of 387 participants for wave 1 and 200 participants for wave 2. Among the 200 persons who completed the study, the mean±SD age was 39.1±15.7 years; 106 were male, 107 were married, 141 were employed, and 38 were students. The participants and those who dropped out did not differ in terms of symptoms of acute stress disorder or demographic characteristics.

Objective severity of exposure was assessed with an item that asked about physical proximity to the explosion. The extent of injury was assessed by using the Injury Severity Score (ISS) (5). Possible scores on this instrument range from 0 to 75, with higher scores indicating more severe injury. The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) (2) and the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire (PDEQ) (3) were used to retrospectively assess distress and dissociation at the time of the traumatic event. Possible scores on the PDI range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating greater distress. Possible scores on the PDEQ range from 10 to 50, where 10 equals no dissociation and higher scores indicate greater dissociation. Symptoms of acute stress disorder were assessed with the global score of the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire (SASRQ) (4). Possible scores on the SASRQ range from 0 to 150, with higher scores indicating greater acute stress symptoms. Participants were asked to check the symptoms of acute stress disorder that they experienced only during the four weeks after exposure. The PTSD Check List Scale (PCLS) (6) was used to assess PTSD symptoms. To be considered as having a high level of PTSD symptoms, participants were required to have a score of at least 50 (6) and to meet the trauma exposure criterion A2.

The significance level was set at .05 (two-sided tests). Missing data were replaced with the mean of all the remaining valid values in the questionnaire of each given respondent. This estimation was done only for respondents for whom fewer than three pieces of data were missing on each questionnaire. This approach was deemed valid in light of the high reliability coefficients and interitem correlations observed for all the study's questionnaires. To analyze the relationship between our predictors and PTSD symptoms, we computed Pearson's correlations and a hierarchical multiple linear regression by using SPSS 10.0.

Results

Severity of exposure could be assessed for 175 participants (88 percent) in wave 2. At the time of the explosion, 33 participants (19 percent) were inside the factory, 80 (46 percent) were within a few blocks of the factory, and 62 (35 percent) were more than a kilometer (.6 mile) away. Only 124 wave 2 participants (62 percent) could be assessed for injury severity. The mean ISS score was 3.6±5.1, which represents a moderate degree of injury. The study participants and those who dropped out of the study did not differ in terms of exposure or injury severity.

Six months after the disaster, 87 of the 200 participants (43 percent) had a high level of PTSD symptoms. No significant differences were noted in the severity of exposure or injury between participants with a low level of PTSD symptoms and those with a high level of PTSD symptoms. Compared with the group with a low level of PTSD symptoms, participants with a high level had higher mean scores on indicators of symptoms of acute stress disorder (94.6±28.2 compared with 61.2±3; t=7.9, df=198, p<.001) as well as higher mean scores on indicators of peritraumatic dissociation (34.2±8.3 compared with 23.8±9.4; t=8.1, df=198, p<.001) and of peritraumatic distress (32.4±7.8 compared with 18±9.8; t=11.2, df=198, p<.001). PTSD symptoms correlated with peritraumatic dissociation (r=.6, p<.001), peritraumatic distress (r=.67, p<.001), and symptoms of acute stress disorder (r=.64, p<.001).

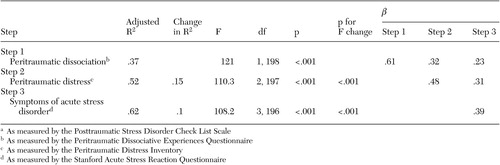

After ruling out collinearity between the predictors, using tolerance and variance inflation factors, we computed a hierarchical multiple linear regression with PTSD symptom score as the dependent variable. Peritraumatic dissociation was entered first; these symptoms have been studied over the past ten years and are known to occur first and to be of short duration. Peritraumatic distress was entered in the second step; this is a recent concept and occurs before acute stress. Symptoms of acute stress disorder were entered in the third step. The model accounted for a total of 62 percent of the variance (Table 1). Changing the order of entry of the variables did not change the fact that each variable accounted for a unique portion of the variance. Moreover, excluding the 11 participants who were under the age of 18 years did not produce significantly altered results.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study confirm previous findings that relate peritraumatic distress (2) and peritraumatic dissociation (1,3,7) as well as symptoms of acute stress disorder (4,8) to PTSD. More important, the results confirm that none of the three concepts acts as a proxy for any of the others. In other words, all three constructs yield unique information that improves significantly our ability to predict who will have unremitting PTSD symptoms six months later. When these three variables were taken into consideration, the predictive power of the study was substantial, accounting for more than 60 percent of the variance.

The prevalence of high levels of PTSD symptoms among the participants in this study appeared to be high compared with other studies (1). It is possible that the method of recruitment introduced a selection bias. One should keep in mind that most of the study participants had also been exposed to images of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Study participants who repeatedly watched "people falling from the towers" had a higher prevalence of PTSD (9). However, given the statistical analyses that we conducted, the absolute level of symptoms was not as important as obtaining enough variance in reported symptoms.

Severity of exposure is often positively correlated to rates of PTSD (1). However, in a study involving a sample of injured victims, the ISS was not a predictor of PTSD (5). In our study in Toulouse, more than a third of the participants were injured despite being more than a kilometer away from the factory when the explosion occurred. This high rate of injury among persons who were far from the epicenter of this event might explain the lack of relation between level of exposure and PTSD symptoms.

Greater current distress may result in greater recollection of dissociation or distress at the time of the trauma, thereby inflating the relationship between peritraumatic or acute symptoms and current PTSD symptoms. Another limitation pertains to the fact that this research began in the immediate aftermath of a national disaster, explaining the choice of a simple study design. Ideally, we would have assessed peritraumatic responses in the days following trauma exposure and symptoms of acute stress disorder within four weeks of trauma exposure. The temporal relationship between distress, dissociation, and symptoms of acute stress disorder could not be examined thoroughly, nor could the individual differences related to development, gender, cultural context, and the nature of the stressor itself. Because the first questionnaire was given five to ten weeks after the trauma, reported symptoms might have been considered not as acute stress disorder but as PTSD. However, participants were asked to check the symptoms of acute stress disorder that they experienced only in the four weeks after exposure. Although replication of these results is needed in order to draw firm conclusions, quantification of both immediate and acute psychological distress may represent one way to trace the experience of a disaster at the community level. The sense of vulnerability and the growing conviction that the world is no longer a safe place often grows into a prediction that something terrible is bound to happen again (10).

Acknowledgments

Dr. Birmes received the financial support of the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, France, while participating in this project, and Dr. Brunet received the financial support of the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec.

Dr. Birmes, Dr. Arbus, and Dr. Schmitt are affiliated with the psychiatry department of the University Hospital of Toulouse in France. Dr. Birmes is also affiliated with the emergency department at the hospital, with which Dr. Coppin-Calmes, Dr. Vinnemann, Dr. Juchet, and Dr. Lauque are affiliated. Dr. Brunet is with the department of psychiatry of McGill University in Montreal, Canada, and with the psychosocial research division of Douglas Hospital Research Center in Montreal. Dr. Coppin is with the emergency department of the General Hospital of Montauban in France. Dr. Charlet is with the epidemiology department of the University Hospital of Toulouse. Send correspondence to Dr. Birmes at Service Universitaire de Psychiatrie et Psychologie Médicale, Hôpital Casselardit, C.H.U. de Toulouse, 170 av. De Casselardit, TSA 40031, 31059 Toulouse Cedex 09, France (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Hierarchical multiple linear regression model predicting symptoms of posttraumatic stress disordera six months after a factory explosion in Toulouse, France (N=200)

1. Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, et al:60,000 disaster victims speak: I. an empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry 65:207–239, 2002Google Scholar

2. Brunet A, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, et al: The peritraumatic distress inventory: a proposed measure of PTSD criterion A2. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1480–1485, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Birmes P, Brunet A, Benoit M, et al: Validation of the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire Self-Report Version in two samples of French-speaking individuals exposed to trauma. European Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

4. Harvey AG, Bryant RA: Two-year prospective evaluation of the relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following mild traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:626–628, 2000Link, Google Scholar

5. Schnyder U, Moergeli H, Trentz O, et al: Prediction of psychiatric morbidity in severely injured accident victims at one-year follow-up. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 164:653–656, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ventureyra VAG, Yao SN, Cottraux J, et al: The validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Check List Scale in posttraumatic stress disorder and nonclinical subjects. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 71:47–53, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Grieger TA, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ: Posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol use, and perceived safety after the terrorist attack on the Pentagon. Psychiatric Services 54:1380–1382, 2003Link, Google Scholar

8. Katz M, Pellegrino L, Pandya A, et al: Research on psychiatric outcomes and interventions subsequent to disasters: a review of the literature. Psychiatric Research 110:201–217, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ahern J, Galea S, Resnick HS, et al: Television images and psychological symptoms after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Psychiatry 65:289–300, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Erikson KT: Trauma at Buffalo Creek. Society 35:153–161, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar