Needs for Services Reported by Adults With Severe Mental Illness and HIV

Abstract

This study examined the needs of people with severe mental illness and HIV. Results were based on interviews and CD4 counts of 294 individuals who received services from the Los Angeles County or the New York City public mental health system. Common unmet needs included financial assistance, housing, and mental health care. Thirty percent of the participants reported that they had at least one basic need that was not being met. Unmet need was less common as HIV infection advanced and was similar in frequency to that found in the general population with HIV. People with severe mental illness and HIV may be benefiting from the special resources that are available for people with HIV.

Persons with psychotic disorders are at increased risk of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (1), and persons with a psychotic disorder and HIV represent the intersection of two groups, each of which is known to have unmet needs. Psychotic disorders often lead to disability and unmet social, medical, and sometimes even subsistence needs (2). HIV progression can also result in disability, economic hardship, and unmet needs (3). Consequently, one would expect that the unmet needs of HIV-positive persons with psychotic disorders would be substantial at early stages of infection and become even more pronounced as HIV progresses. We are aware of only one large study of persons with mental illness and HIV, and that study focused on risk factors for infection (4).

Although no clear consensus exists for what constitutes a need, there is agreement on the importance of consumer perspectives on illness. Needs can be understood from subjective and objective perspectives. The two are correlated, although providers are more likely than clients to identify a need for mental health services (5). We studied subjective need in a population with psychotic disorders and HIV who were receiving care in the Los Angeles County or the New York City public mental health system. We assessed the relationship between predisposing, enabling, and disease characteristics (6) and unmet needs for financial assistance, housing, mental health care, drug or alcohol treatment, and home health care.

Methods

Clients were recruited from all publicly funded mental health agencies in Los Angeles County between September 1998 and August 1999 and in New York City between August 1999 and May 2002. Clinicians at agencies referred clients who had been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or depression with psychosis before they had been infected with HIV. Diagnoses were determined by the client's primary clinician. In Los Angeles County 154 out of 252 eligible clients (61 percent) were interviewed. In New York City 140 out of 178 eligible clients (79 percent) were interviewed. All participants gave informed consent and were asked to provide blood for a CD4 count. The study was approved by the RAND institutional review board.

The survey was modified from the instrument used in the national HIV Cost and Service Utilization Study to make it more understandable to persons with psychotic disorders (7). The survey included sections on insurance and benefits, drug and alcohol abuse, strength of social support, instrumental functioning, quality of life, mental health and HIV service use, access, and satisfaction (8). Project staff conducted two pilot tests of the survey among patients with severe mental illness. Each pilot test was followed by revisions to the instrument. Final interviews were conducted by RAND staff members who were extensively trained in the use of the instrument.

Needs were assessed by asking whether respondents had needed financial assistance, housing, mental health care, and drug or alcohol treatment in the past six months. Respondents who lived in independent housing (154 participants, or 52 percent) were also asked whether they needed home health care. For each need that was reported, participants were asked whether they received help in meeting that need. Response options were "did not need help," "no," "yes, but not as much as I needed," and "yes, as much as I needed." We defined participants with unmet needs as those who identified a need and either did not receive any help or did not get as much help as they needed.

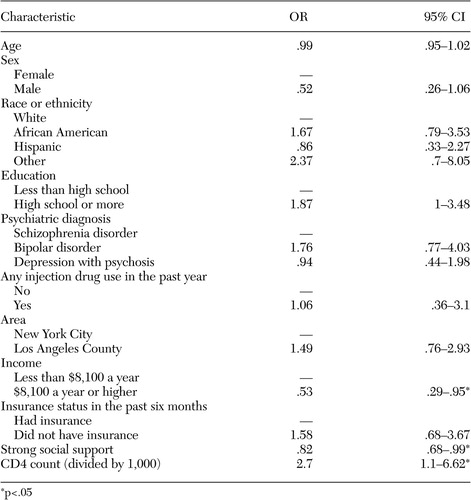

Multivariate logistic regression was used to study factors that affected having at least one unmet need. The model included predisposing factors (age, sex, race or ethnicity, education level, psychiatric diagnosis, injection drug use in the past year, and city of residence), enabling factors (income, insurance, and social support), and HIV progression (CD4 count). Secondary bivariate analyses were used to study other factors associated with having unmet need: instrumental functioning, quality of life, number of mental and HIV treatment visits, whether mental health and HIV treatment were received from the same site, whether HIV education was received, access to medical care, and satisfaction with mental health care.

Results

Of the 294 participants, 207 participants (70 percent) were male. The mean±SD age of the participants was 40.8±7.9 years. Seventy-three participants (25 percent) were white, 150 (51 percent) were African American, 54 (18 percent) were Hispanic, and 16 (5 percent) were of another race or ethnicity. A total of 165 participants (56 percent) had completed high school, and 132 (45 percent) were currently employed full- or part-time. The median annual income of the participants was $8,100. A total of 230 participants (78 percent) were insured by Medicaid, either alone or in combination with other insurance. Other participants were insured by Medicare (80 participants, or 27 percent), the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (69 participants, or 24 percent), the Department of Veterans Affairs (16 participants, or 5 percent), and private insurance (14 participants, or 5 percent). Thirty-five participants (13 percent) did not have any insurance in the past six months. Sixty-one participants (21 percent) were given a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; 91 (31 percent), bipolar disorder; and 142 (48 percent), depression with psychosis. Eighty-six participants (29 percent) reported that they had received a diagnosis of AIDS, and 273 (95 percent) reported that they were receiving care for HIV.

Participants in New York City and Los Angeles County were compared with regard to demographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnoses, HIV risk factors, and HIV illness severity. Participants in New York City were significantly more likely to be female (63 participants, or 45 percent, compared with 24 participants, or 16 percent; χ2=30.5, df=1, p<.001), more likely to be African American (91 participants, or 65 percent compared with 59 participants, or 38 percent) or Hispanic (32 participants, or 23 percent, compared with 22 participants, or 14 percent), and less likely to be white (12 participants, or 9 percent, compared with 61 participants, or 40 percent; χ2=43.9, df=3, p<.001). On average, participants in New York City were about three years older than participants in Los Angeles County (mean±SD age of 42.3±7.8 years compared with 39.4±7.7 years; t=3.3, df=292, p<.001). Participants in New York City were less likely to have a high school diploma (63 participants, or 45 percent, compared with 102 participants, or 66 percent; χ2=13.4, df=1, p<.001) and less likely to be uninsured during the past six months (two participants, or 2 percent, compared with 33 participants, or 24 percent; χ2=30.4, df=1, p<.001). A greater percentage of participants in Los Angeles County had recently injected drugs (19 participants, or 12 percent, compared with one participant, or 1 percent; χ2=15.6, df=1, p<.001). Participants at the two sites did not differ at p<.05 with regard to psychiatric diagnosis, income in the past 30 days, level of social support, or CD4 count.

Overall, 187 respondents (64 percent) reported having at least one need. The most common reported needs were for additional mental health care (145 participants, or 49 percent), followed by financial assistance (76 participants, or 26 percent), housing (72 participants, or 25 percent), drug or alcohol treatment (37 participants, or 13 percent), and home health care (34 participants, or 12 percent). Of the 187 who reported having a need, 87 (47 percent) stated that at least one of their needs was unmet. Unmet need (unmet need among persons who needed the service) was reported to be greatest for financial assistance (49 of 76 participants, or 64 percent), followed by housing (29 of 72 participants, or 40 percent), home health care (seven of 34 participants, or 21 percent), mental health care (45 of 145 participants, or 31 percent), and drug or alcohol treatment (seven of 37 participants, or 19 percent).

Table 1 shows that enabling factors and disease characteristics were associated with a significantly increased risk of having an unmet need. Secondary analyses revealed no significant correlations between CD4 count and types of health care insurance. Analyses of service use and functioning characteristics revealed that participants who had unmet needs were less satisfied with access to physical and mental health care, less likely to have received counseling about HIV, and more likely to have a history of drug dependence (p<.05 for each).

Discussion

This study is the first to report on the needs of a population with severe mental illness who have comorbid HIV. Thirty percent of the participants reported having at least one unmet need in the previous six months. Compared with the results of a previous study on the national population of people in treatment for HIV (9), our study found similar overall levels of unmet need, more unmet need for financial assistance (64 percent compared with 35 percent) and housing (40 percent compared with 16 percent), and less unmet need for substance abuse treatment (19 percent compared with 28 percent). Comparisons with the overall population of people with severe mental illness is difficult, because need varies substantially by geographic region and we are not aware of any systematic studies in New York City or Los Angeles County. Compared with previous studies in other regions, our study showed that our sites have levels of unmet need that are relatively high for housing and financial assistance, low for medical care, and comparable for mental health care (10).

Unmet needs were more common in certain vulnerable groups. Contrary to our hypotheses, participants with lower CD4 counts were actually less likely to report having unmet needs. Individuals with more advanced HIV disease qualify for additional assistance, which may have helped them meet their needs. When interviewing clinicians and managers at the sites, we consistently heard that clients with mental illness and HIV are much better off than those with mental illness and a non-HIV medical disorder. Persons with HIV are eligible for and receive an extensive set of services. The Ryan White Act targets substantial special resources for people with HIV. For example, people with HIV in New York become eligible for housing when their CD4 counts fall below a certain level.

This study was limited to Los Angeles County and New York City, and unmet needs may be quite different in other geographic regions. Other limitations include our focus on a specific set of basic needs, our response rate of 68 percent, and the fact that we did not confirm psychiatric diagnoses by structured research interview. Also, all respondents were in mental health treatment and known to have HIV. People who are not receiving mental health care or whose HIV has not been detected may have different needs.

Conclusions

Persons with severe mental illness may have limited access to important services and substantial unmet need (2,10). This study examined a subpopulation with HIV and found that overall unmet need was less common as HIV advanced and similar in overall magnitude to unmet need in the general population with HIV. The additional resources available to those with HIV appear to be benefiting all persons with this illness, including those with severe mental illness.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants MH-559-36 and MH-0686-39 from the National Institute of Mental Health; by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Desert Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC); and by the VA South Central MIRECC. The authors thank Francine Cournos, M.D., Karen McKinnon, M.A., and Judith Perlman, M.A., of the RAND Survey Research Group and Jim Satriano, Ph.D., for their contributions to the project.

The authors are affiliated with RAND in Santa Monica, California. Dr. Young is also with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC), 11301 Wilshire Boulevard, 210A, Los Angeles, California 90073. Dr. Sullivan is also with Little Rock VA Medical Center, MIRECC in North Little Rock, Arkansas.

|

Table 1. Multivariate logistic regression results indicating associations between predisposing, enabling, and disease characteristics and unmet need among 294 persons with psychotic disorders and HIV who received services from the Los Angeles County or the New York City public mental health system

1. Cournos F, McKinnon K: HIV seroprevalence among people with severe mental illness in the United States: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review 17:259–269, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Young AS, Magnabosco JL: Services for adults with mental illness, in Mental Health Services: A Public Health Perspective. Edited by Levin BL, Petrila J, Hennessy KD. New York, Oxford University Press, 2004Google Scholar

3. Bonuck KA, Arno PS, Green J, et al: Self-perceived unmet health care needs of persons enrolled in HIV care. Journal of Community Health 21:183–198, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Brunette MF, Drake RE, Marsh BJ, et al: Responding to blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:860–865, 2003Link, Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck R, Lam JA: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381–386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

6. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

7. Bozzette SA, Berry SH, Duan N, et al: The care of HIV-infected adults in the United States: HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study Consortium. New England Journal of Medicine 339:1897–1904, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Tucker JS, Kanouse DE, Miu A, et al: HIV risk behaviors and their correlates among HIV-positive adults with serious mental illness. AIDS and Behavior 7:29–40, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Katz MH, Cunningham WE, Mor V, et al: Prevalence and predictors of unmet need for supportive services among HIV-infected persons: impact of case management. Medical Care 38:58–69, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. McCrone P, Leese M, Thornicroft G, et al: A comparison of needs of patients with schizophrenia in five European countries: the EPSILON Study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 103:370–379, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar