Ethnicity and Prescription Patterns for Haloperidol, Risperidone, and Olanzapine

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Patients with schizophrenia may respond better to second-generation antipsychotics than to older antipsychotics because of their superior efficacy and safety profiles. However, the reduced likelihood among ethnic minority groups of receiving newer antipsychotics may be associated with reduced medication adherence and health service use, potentially contributing to poor response rates. This study examined whether ethnicity helped predict whether patients with schizophrenia were given a first- or a second-generation antipsychotic, haloperidol versus risperidone or olanzapine, and what type of second-generation antipsychotic was prescribed, risperidone or olanzapine, when other factors were controlled for. METHODS: Texas Medicaid claims were analyzed for persons aged 21 to 65 years with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who started treatment with olanzapine (N=1,875), risperidone (N=982), or haloperidol (N= 726) between January 1, 1997 and August 31, 1998. The association between antipsychotic prescribing patterns among African Americans, Mexican Americans, and whites was assessed by using logistic regression analysis. Covariates included other patient demographic characteristics, region, comorbid mental health conditions, and medication and health care resource use in the 12 months before antipsychotic initiation. RESULTS: The results of the first- versus second-generation antipsychotic analysis indicated that African Americans were significantly less likely than whites to receive risperidone or olanzapine. Although not statistically significant, the odds ratio indicated that Mexican Americans were also less likely to receive risperidone or olanzapine. Ethnicity was not associated with significant differences in the prescribing patterns of risperidone versus olanzapine. CONCLUSIONS: When other factors were controlled for, African Americans were significantly less likely to receive the newer antipsychotics. Among those who received the newer antipsychotics, ethnicity did not affect medication choice.

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that by 2050, nearly half of the U.S. population will be of African-American, Latino, Asian-American, Pacific-Islander, or Native-American descent (1). As a result, it is becoming more important for health care practitioners to acknowledge and understand ethnic differences in health care use.

Studies have suggested that culture and ethnicity affect the diagnoses, course of treatments, and medical and prescription drug use patterns of patients with schizophrenia (2,3,4,5,6,7). African Americans have been found to be more likely than whites to be given a diagnosis of schizophrenia than a mood disorder, to receive antipsychotic dosages in excess of the recommended range, and to delay seeking health care services (8,9,10). Little has been published about psychiatric diagnosis or antipsychotic use among Mexican Americans. The recent confirmation of the gaps in health care equality between minorities and whites in America underscores the importance of identifying and correcting inequitable practices (10).

The traditional pharmacologic treatment for many patients with schizophrenia has been the use of conventional, or first-generation, antipsychotics, such as haloperidol. However, research has shown that patients with schizophrenia may respond better to atypical, or second-generation, antipsychotics, such as risperidone or olanzapine. Second-generation antipsychotics show similar or improved efficacy with regard to positive symptoms, exhibit an improved extrapyramidal symptoms profile, are effective against negative symptoms, and reduce the risk of tardive dyskinesia (11,12,13,14,15). First- and second-generation antipsychotics also differ in acquisition costs, with second-generation antipsychotics being several times more expensive. However, second-generation antipsychotics may be more cost-effective over time because hospitalizations and specialist treatments of patients may be prevented (16,17).

Studies have shown that persons from ethnic minority groups may be less likely than whites to receive second-generation antipsychotic medications (10,18,19). Particular concern arises around racial disparities in care found among similarly insured individuals because health insurance is generally considered to be the "great equalizer" in the health system (1). To avoid this potential confounding variable, this study compared patients in the Texas Medicaid system who were similarly insured and had similar incomes.

The two main objectives of this study were to examine if ethnicity helped to predict whether Texas Medicaid patients received prescriptions for a first- or a second-generation antipsychotic, haloperidol versus risperidone or olanzapine, and what type of second-generation antipsychotic was prescribed, risperidone or olanzapine.

Methods

Data source

Medical claims data were extracted from the Texas Medicaid Management Information System (MMIS), and pharmacy claims data were extracted from the Texas Vendor Drug Program paid prescription claims database. In addition, information related to individual patient enrollment periods was extracted from the eligibility files maintained by the Texas Department of Human Services.

Study population

Individual patient-level claims records for services and medications provided between January 1, 1996, and August 31, 1998, were extracted and analyzed in order to encompass the 12 months before the index period: January 1, 1997, through August 31, 1998. This study analyzed data for patients who were between 21 and 65 years of age at the time of antipsychotic initiation; were initiated on haloperidol, risperidone, or olanzapine during the index period; had not taken haloperidol, risperidone, or olanzapine in the 12 months before the antipsychotic initiation; had at least one recorded inpatient hospital claim or at least two recorded outpatient or ambulatory visit claims with an accompanying primary or secondary diagnosis related to schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (ICD-9M code of 295.XX) in the 12 months before the antipsychotic initiation; and were eligible for Medicaid 12 months before the antipsychotic initiation.

Variables

The variable of interest, or dependent variable, for the first objective was whether the index drug prescribed was a first-generation antipsychotic, haloperidol (coded as 0), or a second-generation antipsychotic, risperidone or olanzapine (coded as 1). For the second objective, the dependent variable was whether the index drug was risperidone (coded as 0) or olanzapine (coded as 1).

Potential predictive factors included demographic characteristics, comorbid mental health conditions, medication history, earlier service use, and clinical severity. Direct measures of clinical severity were not available in the data set. However, measures of the other predictive factors were available and were controlled for. Predictive factors included dummy variables to capture gender; three categories of ethnicity, which included white, African American, and Mexican American; ten regions, which included Austin, San Antonio, Fort Worth, Lubbock, Houston, Dallas, Galveston, El Paso, Waco, and other; three comorbid psychiatric conditions, which included bipolar disorder, substance abuse, and other mental illness; and three independent categories of antipsychotic use—which included clozapine, depot, and second-generation antipsychotics other than clozapine—in the 12 months before antipsychotic initiation. In addition, continuous independent variables were included that represented age; the number of different antipsychotic medications, except for clozapine and depot, used in the 12 months before the antipsychotic initiation; and the number of outpatient physician visits, emergency department visits, and inpatient hospital days in the 12 months before the antipsychotic initiation. Variables indicating region were included in the analysis, because regional variations in ethnic composition and medication prescribing patterns might otherwise confound the analysis.

Statistical analyses

For descriptive purposes, the mean or prevalence of each independent variable was calculated for use in univariate comparisons between the first- and second-generation antipsychotic groups and between the olanzapine and risperidone groups; t tests, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs), and chi square analyses were used for these comparisons. To evaluate the influence of ethnicity on antipsychotic prescribing patterns, two multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed on the data, simultaneously including all of the independent variables. The first logistic regression was used to predict the odds of receiving a second-generation antipsychotic, risperidone or olanzapine, instead of a first-generation antipsychotic, haloperidol. The second logistic regression was performed to predict the odds of receiving olanzapine instead of risperidone. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (20) with an alpha level of .05.

Results

A total of 3,583 patients met the criteria for the first logistic regression analysis, including 726 patients taking haloperidol, 982 patients taking risperidone, and 1,875 patients taking olanzapine. A total of 2,857 patients were included in the second logistic regression analysis, including 982 patients taking risperidone and 1,875 patients taking olanzapine.

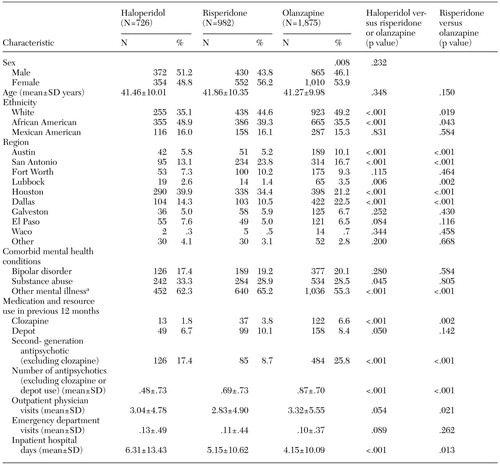

Table 1 describes the characteristics of patients who were initiated on each of the antipsychotic medications. Significant differences in some patient characteristics were seen between those who received first- and second-generation antipsychotics and between those who received olanzapine and risperidone.

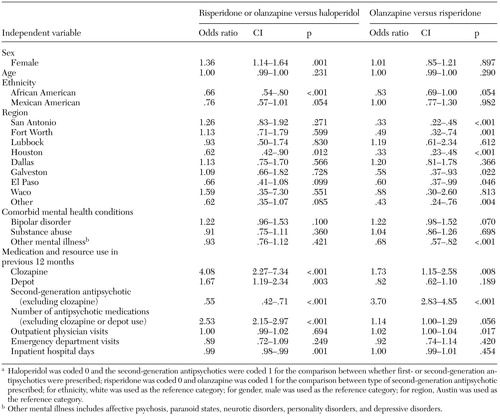

The left half of Table 2 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis that was used to predict the odds of receiving a second-generation antipsychotic instead of a conventional antipsychotic. The odds ratios indicated that African Americans, patients from Houston, patients who had previously used second-generation antipsychotics, and patients who had more inpatient hospital days in the 12 months before the antipsychotic initiation were less likely to receive a second-generation antipsychotic. Being female, having previously used clozapine or depot medication, and having previously used a large number of antipsychotic medications were all associated with an increased chance of receiving a second-generation antipsychotic.

The right half of Table 2 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis that was used to predict the odds of receiving olanzapine instead of risperidone. The odds ratios indicated that patients from San Antonio, Fort Worth, Houston, Galveston, El Paso, or "other" regions, and patients with an "other" comorbid mental heath condition were less likely to receive olanzapine. Previous clozapine use, previous second-generation antipsychotic use, and having a high number of previous outpatient physician visits were all associated with an increased chance of receiving olanzapine. Ethnicity was not a significant predictor of which second-generation antipsychotic was prescribed.

Discussion

Haloperidol versus risperidone or olanzapine

African Americans were significantly less likely to receive a second-generation antipsychotic than whites. Differences in symptom expression and presentation between different ethnic groups may be one explanation (6). Some studies have found that African Americans have presented with more paranoia and more positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, and fewer negative symptoms, such as attentional impairment and alogia, than white patients (2,3). Subtle differences in the presentation of symptoms may cause clinicians to interpret the symptoms differently, therefore affecting the diagnoses and treatment choices (5). Trouble understanding one another and communicating across cultures can also influence diagnoses and prescribing patterns (6,21). Although not statistically significant, the odds ratio indicated that Mexican Americans were also less likely to receive second-generation antipsychotics. This lower likelihood of using second-generation antipsychotics may negatively affect both medication adherence and outcomes (15).

Similar findings of disparities in health care among ethnic groups have been reported in the antidepressant literature as well. Studies have found that African Americans were less likely than whites to receive antidepressants (22,23). Discrimination is one possible explanation for the gap in health care equality among ethnic groups. Loring and Powell (7) found that the race of the client and the psychiatrist influences the diagnosis, even when clear-cut diagnostic criteria are presented. Ren and colleagues (24) found in their analysis of patients with depression that African Americans were disproportionately exposed to discrimination. Williams and colleagues (25) also found evidence of discrimination toward African Americans in their study that examined physical and mental health. Inappropriate expectations can lead to inappropriate decisions and actions.

Table 2 also shows that individuals with previous clozapine use, previous depot use, and more previous antipsychotic medications were more likely to receive a second-generation antipsychotic. These results indicate that second-generation antipsychotics may be favored for patients who present more severe symptoms or who are treatment resistant (15,26). A possible explanation for patients with previous second-generation antipsychotic use being less likely to receive a second-generation antipsychotic is that a previous failed attempt at second-generation antipsychotic therapy led to the increased chance that a first-generation antipsychotic would be prescribed.

Risperidone versus olanzapine

Although ethnicity did not appear to be a significant predictor in this analysis, other factors resulted in important findings. Having previous use of clozapine, previous use of second-generation antipsychotics, and more previous outpatient physician visits were all indicators of a higher likelihood of receiving olanzapine than risperidone. From these results, it appears that patients who had more severe symptoms or who were treatment resistant were initiated on olanzapine. Research studies have shown that olanzapine may have greater efficacy than risperidone among patients with chronic schizophrenia (27). A possible explanation for why patients who had previously used clozapine received prescriptions for olanzapine is that both of these medications are pharmacologically similar (28).

Another interesting finding from this analysis was the notable difference among various regions of Texas in the likelihood of receiving olanzapine or risperidone, even with simultaneous adjustment for ethnic differences. Such regionwide differences probably indicate system-level influences on prescribing practices.

Certain limitations must be considered when interpreting these results. The socioeconomic status of Medicaid patients is not representative of the general population, and Texas Medicaid patients with schizophrenia may not be representative of other states' Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. On the other hand, restricting this analysis to Medicaid clients increases the economic homogeneity of the study population; therefore, the results are not likely to be confounded by unmeasured economic factors. Another limitation is that diagnostic codes were used to identify patients with schizophrenia within the claims data instead of using formal diagnostic assessments. Lastly, sociodemographic factors closely related to ethnicity may be at least partly responsible for the effects observed, such as differences in providers used within a region.

Future research might examine whether the type of antipsychotic prescribed is affected by ethnic matching of prescribers and patients. Incorporating patients from additional ethnic groups into similar analyses or investigating gender differences may also provide a deeper understanding of the findings. In addition, examining the differences in prescribing patterns of antipsychotic medications between primary care physicians and specialists may yield important results. Finally, this study's results might be generalized with greater confidence if the study were replicated in a multistate Medicaid patient population or in study populations other than Medicaid beneficiaries.

Conclusions

This study examined prescription drug use data for Texas Medicaid patients with schizophrenia to see whether ethnicity was associated with antipsychotic prescribing patterns. African Americans were significantly less likely than whites to receive a second-generation antipsychotic. However, there was no significant difference between Mexican Americans and whites in the likelihood of receiving a first- or a second-generation antipsychotic. Ethnicity was not a significant predictor of receiving risperidone versus olanzapine.

Acknowledgment

Eli Lilly & Company provided the funding for this research.

Ms. Opolka is affiliated with Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc., 475 Half Day Road, Lincolnshire, Illinois 60069 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Rascati and Dr. Brown are with the University of Texas at Austin College of Pharmacy. Dr. Gibson is with the Health and Hospital Corporation of Marion County, Indianapolis, Indiana. At the time of the study, Ms. Opolka and Dr. Gibson were affiliated with the department of U.S. outcomes research at Eli Lilly & Company in Indianapolis.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of Texas Medicaid patients who initiated treatment on olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol between January 1, 1997, and August 31, 1998, by type of antipsychotic prescribed

|

Table 2. Multivariate logistic regression results of the type of antipsychotic prescribed regressed on the independent variables for Texas Medicaid patients who intiated treatment on olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol between January 1, 1997, and August 31, 1998a

a Haloperidol was coded 0 and the second-generation antipsychotics were coded 1 for the comparison between whether first- or second-generation antipsychotics were prescribed; risperidone was coded 0 and olanzapine was coded 1 for the comparison between type of second-generation antipsychotic prescribed; for ethnicity, white was used as the reference category; for gender, male was used as the reference category; for region, Austin was used as the reference category.

1. Lillie-Blanton M, Hoffman C: Racial and ethnic inequities in access to medical care: introduction. Medical Care Research and Review 57(suppl 1):5–10, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

2. Fabrega H, Mezzich J, Ulrich RF: African-American-white differences in psychopathology in an urban psychiatric population. Comprehensive Psychiatry 29:285–297, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lawson WB: Racial and ethnic factors in psychiatric research. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:50–54, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Morse JK, Johnson DJ, Heyliger SO: Understanding ethnic disparities in the treatment of affective disorders. Minority Health Today 2:24–27, 2000Google Scholar

5. Adebimpe VR: Race, racism, and epidemiological surveys. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:27–31, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Jeste DV, Lindamer LA, Evans J, et al: Relationship of ethnicity and gender to schizophrenia and pharmacology of neuroleptics. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 32:243–251, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

7. Loring M, Powell B: Gender, race, and DSM-III: a study of the objectivity of psychiatric diagnostic behavior. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 29:1–22, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Neighbors HW, Trierweiler SJ, Munday C, et al: Psychiatric diagnosis of African Americans: diagnostic divergence in clinician-structured and semistructured interviewing conditions. Journal of the National Medical Association 91:601–612, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

9. Walkup JT, McAlpine DD, Olfson M, et al: Patients with schizophrenia at risk for excessive antipsychotic dosing. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:344–348, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Burroughs VJ, Maxey RW, Levy RA: Racial and ethnic differences in response to medicines: towards individualized pharmaceutical treatment. Journal of the National Medical Association 94:1–26, 2002Google Scholar

11. Worrel JA, Marken PA, Beckman SE, et al: Atypical antipsychotic agents: a critical review. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacists 57:238–258, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Abraham D, et al: Efficacy and extrapyramidal side-effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophrenia Research 35:51–68, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Frankenburg FR: Choices in antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 6:241–249, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Purdon SE, Jones BDW, Stip E, et al: Neuropsychological change in early phase schizophrenia during 12 months of treatment with olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:249–258, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Edgell ET, Andersen SW, Johnstone BM, et al: Olanzapine versus risperidone: a prospective comparison of clinical and economic outcomes in schizophrenia. Pharmacoeconomics 18:567–579, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kendrick T: The newer, "atypical" antipsychotic drugs—their development and current therapeutic use. British Journal of General Practice 49:745–749, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

17. Foster RH, Goa KL: Olanzapine: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in schizophrenia. Pharmacoeconomics 15:611–640, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lawson WB: Clinical issues in the pharmacotherapy of African-Americans. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 32:275–281, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kuno E, Rothbard A: Racial disparities in antipsychotic prescription patterns for patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:567–572, 2002Link, Google Scholar

20. SPSS 10.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc, Chicago, 1999Google Scholar

21. Frackiewicz EJ, Sramek JJ, Collazo Y, et al: Risperidone in the treatment of Hispanic schizophrenic patients, in Cross Cultural Psychiatry, Edited by Herrera JM, Lawson WB, Sramek JJ. England, Wiley, 1999Google Scholar

22. Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Simonsick EM, et al: Marked differences in antidepressant use by race in an elderly community sample:1986–1996. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1089–1094, 2000Google Scholar

23. Melfi C, Croghan T, Hanna M, et al: Racial variation in antidepressant treatment in a Medicaid population. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:16–21, 1997Google Scholar

24. Ren XS, Amick BC, Williams DR: Racial/ethnic disparities in health: the interplay between discrimination and socioeconomic status. Ethnicity and Disease 9:151–165, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

25. Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS: Racial differences in physical and mental health. Journal of Health Psychology 2:335–351, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Buckley PF: Broad therapeutic uses of atypical antipsychotic medications. Biological Psychiatry 50:912–924, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, et al: Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:255–262, 2002Link, Google Scholar

28. Seeman P: Atypical antipsychotics: mechanism of action. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 47:27–38, 2002Medline, Google Scholar