Trauma History Screening in a Community Mental Health Center

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed the lifetime prevalence of traumatic events among consumers of a community mental health center by using a brief trauma screening instrument. This study also examined the relationship between trauma exposure and physical and mental health sequelae and determined whether the routine administration of a trauma screening measure at intake would result in increased diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and in changes in treatment planning in a practice setting. METHODS: A 13-item self-report trauma screening instrument, a shortened version of the Trauma Assessment of Adults instrument, was incorporated into the intake assessment process at a community mental health center (CMHC). A total of 505 out of 515 consumers who presented to the CMHC consecutively were surveyed from May 1, 2001, to January 31, 2002. Data from the initial assessment on trauma exposure and on rate of PTSD diagnosis were examined, and a chart review was conducted on 97 cases (19 percent) to determine the extent to which CMHC services addressed trauma-related problems. RESULTS: Data indicated that 460 consumers (91 percent) had been exposed to one or more traumatic life experiences. The number of traumatic events was negatively correlated with physical and mental health functioning on the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12). Subjects with a history of sexual abuse scored significantly higher on the SF-12, reflecting poorer physical and mental health. Although the rate of PTSD diagnosis increased after implementation of the trauma screening instrument, the rates of actual PTSD treatment services provided did not change. CONCLUSIONS: This study strongly suggests that screening for trauma history should be a routine part of mental health assessment and may significantly improve the recognition rate of PTSD. However, much work remains to be done in implementing appropriate treatment.

A substantial body of literature documents that individuals experience traumatic events far more commonly than previously believed. Epidemiological studies estimate that between 36 and 81 percent of the general population experience a traumatic event at some time in their lives (1,2,3). An even higher lifetime rate of traumatic events is estimated in clinical populations, particularly for consumers of public mental health services. Studies of public mental health consumers have found that between 48 and 98 percent of clients reported a history of at least one traumatic event (4,5,6). Similarly, studies examining posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among mental health consumers have found high rates of PTSD in this population (34 to 43 percent) (5,7), far exceeding PTSD rates found in the general population (8 percent) (3).

Identifying an individual's trauma exposure history is important because of the serious psychosocial impairments associated with PTSD. Numerous studies discuss the significant comorbidity found in individuals with PTSD (8). In many cases PTSD predates the onset of other psychiatric diagnoses, and in some cases PTSD may be a risk factor for developing other psychiatric disorders. For example, survival analysis of data from the National Comorbidity Survey indicates that individuals with PTSD are significantly more likely to develop other anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders than respondents without PTSD. Subjects with PTSD were also found to be six times as likely as demographically matched controls to attempt suicide (8). Furthermore, PTSD is also associated with some of the highest rates of service use, costs, and role impairment of any disorder (9,10).

Once individuals with PTSD are identified, effective treatments do exist (11,12), although the use of these treatments for public mental health consumers, who often have a serious comorbid mental illness, is underexplored. In addition, many public-sector clinicians have not received training in PTSD interventions (13). In fact, most public-sector mental health clinics are not even assessing trauma history, making identification of PTSD very difficult (14,15). One study found that the actual prevalence of PTSD in four community mental health centers was 43 percent; yet this diagnosis had been documented in only 2 percent of these cases (5).

The study reported here was undertaken to examine the lifetime prevalence of traumatic events among a sample of consumers at a community mental health center (CMHC), to determine the differential risk for trauma exposure on the basis of gender and race, to examine the relationship between trauma exposure and physical and mental health sequelae, and to determine whether routine administration of a trauma screening measure at intake would result in increased diagnoses of PTSD and in changes in treatment planning in a practice setting.

Method

The setting

The CMHC where the study was conducted is one of 17 publicly funded mental health centers located in South Carolina. The CMHC serves more than 6,000 consumers each year from urban and rural areas who have a serious and persistent mental illness as well as those who are in acute crisis. The consumer population is 52 percent African American, 45 percent white, and 3 percent other. Adult services for the CMHC are divided into case management, short-term therapy, and psychosocial rehabilitation services. In 1999 the South Carolina Department of Mental Health implemented a statewide "trauma initiative," with the goal of improving the services provided to trauma survivors through appropriate screening, assessment, and empirically based clinical interventions. Our study reports outcomes from the improved screening efforts at the CMHC from May 1, 2001, to January 31, 2002.

Instruments

Screening for a lifetime history of traumatic events was done by using a shortened version of the Trauma Assessment for Adults (TAA) (unpublished instrument, Resnick GS, Best CL, Freedy JR, et al, 1993). The TAA is a self-report instrument that addresses 12 specific events plus an "other" category with a "yes" and "no" response format. The TAA items are based on the Potential Stressful Events Interview used in the DSM-IV field trial (unpublished instrument, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Freedy JR, 1991). The TAA's validity is supported by a previous study in which the TAA identified rates of general trauma and crime exposure that were highly consistent with findings from another structured assessment (16). In addition, archival data that reflected clinician's reports of a traumatic event history were compared with TAA data, and in each case the TAA identified the presence of traumatic events (16). The TAA was modified for our study by simplifying some of the language in the instructions to make it easier for consumers with limited education to understand and omitting additional questions related to each event, such as "age at first time," "age at last time," "did you feel fear/helplessness/horror?" At the same time that the shortened TAA was implemented at intake in the CMHC, supervisors instructed case managers to administer the full-length TAA if a new client screened positive for trauma history at intake, so additional details could be gathered.

The 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) was included at intake as a measure of general health status (17,18). The SF-12 is a self-report shortened version of the widely used SF-36 and has strong psychometric properties. Items are rated on a Likert scale response format. The SF-12 yields a subscale for physical health and mental health and has well-developed norms.

The PTSD Checklist is a 17-item self-report measure of PTSD symptoms based on DSM-IV criteria, with a 5-point Likert scale response format (19,20). It is highly correlated with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (r=.929), has good diagnostic efficiency (>.70), and has robust psychometric properties with a variety of trauma populations. Furthermore, recent data show that PTSD diagnoses can be reliably assessed among public-sector consumers with serious mental illness (5). Supervisors instructed case managers to administer the PTSD Checklist to any new client who screened positive for trauma history at intake.

Procedure

This study reported findings from the analysis of archival data and was deemed exempt according to the South Carolina Department of Mental Health institutional review board. In April 2001 all intake clinicians were given a 60-minute training session about traumatic events and PTSD through the Department of Mental Health trauma initiative. Specifically, the training consisted of a review of the full-length and the shortened TAA and of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD (21). The intake clinicians were instructed to administer the shortened TAA as a self-report instrument to each consumer who presented for services and to read the questions to anyone unable to read. They were also instructed to use clinical judgment to determine whether psychosis or impaired intellectual functioning would preclude the consumer from filling out the form.

Beginning May 1, 2001, all adults who presented for services at the CMHC intake unit were given the SF-12 health survey and the shortened TAA inventory to fill out at the beginning of their intake appointment. The clinician then reviewed the questionnaire and incorporated this information into the intake interview. The diagnoses assigned during intake were clinical diagnoses based on DSM-IV criteria; however, no PTSD diagnostic instrument was added to this procedure. As a further clinical practice change recommended by the trauma initiative, case managers at the CMHC were instructed to administer the longer TAA and the PTSD Checklist to all new clients who screened positive at intake for trauma exposure.

Trauma screening data were gathered on 505 out of 515 individuals who presented for services consecutively between May 1, 2001, and January 31, 2002. The ten consumers who were not surveyed were judged to be either too ill to complete the shortened TAA or in acute crisis at the time of intake and unable to complete it.

A chart review was conducted for 97 randomly selected charts (19 percent). The charts were examined to gather additional descriptive information about consumers and to determine how well the trauma screening information was addressed by case managers: Did the case manager review and gather additional details about traumatic events? Was the PTSD Checklist administered? If appropriate, did treatment goals address trauma-related symptoms? The information collected during the chart review included the most recent documented psychiatric diagnoses, whether the psychiatric diagnosis had changed from the time of intake, psychiatric medications prescribed, use of the full-length TAA and the PTSD Checklist instruments, and a review of both the treatment plan and the clinical notes for attention to trauma history and PTSD. For purposes of our study, a notation was made when the chart listed any trauma exposure beyond that detected by the modified TAA or listed any PTSD symptoms or PTSD treatment goals, for example, PTSD symptom targets or references to discussion of trauma exposure.

Treatment plans at the CMHC include the consumer's diagnosis, specific treatment goals, and specific interventions to address these goals. The treatment plans are signed by the assigned case manager, psychiatrist, and consumer and are intended to be a document that guides the course of treatment.

Analysis

Chi square analyses were conducted to examine differences between gender and racial groups on trauma exposure. Chi square analyses were also computed to compare the presence of PTSD diagnosis on the basis of the type of trauma exposure. One-way analyses of variance were used to determine whether particular types of trauma exposure led to higher scores on the SF-12, indicating poorer functioning for physical and mental health. Pearson correlations were obtained between the number of different lifetime trauma events and SF-12 scores. Finally, a logistic regression on PTSD was used to determine the types of traumatic events that were predictive of receiving a diagnosis of PTSD at intake.

Results

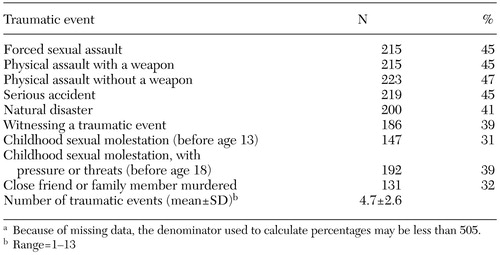

The mean±SD age of the sample was 37±11.6 years. A total of 316 consumers were female (68 percent), 151 were male (32 percent) 289 were Caucasian (61 percent), 162 were African American (35 percent), and 16 were of another race (4 percent). (Because of missing data, the denominator used to calculate percentages may by less than 505.) Out of the 505 consumers in the sample, 431 consumers (91 percent) completing the shortened TAA reported exposure to at least one type of traumatic event. Among those exposed to a traumatic event, consumers reported an average of 4.7 different types of traumatic events. Out the 505 consumers sampled, 264 consumers (55 percent) had experienced some type of sexual abuse, 276 (58 percent) had experienced a physical assault, and 186 (37 percent) had witnessed violence. There were 115 consumers (26 percent) and 59 consumers (15 percent) who reported experiencing the homicide or the killing by a drunk driver, respectively, of a family member or friend. Rates of each type of specific trauma are presented in Table 1.

Analyses of gender and racial differences revealed two differences in trauma exposure. Women were more likely to experience any sexual trauma (198 women, or 63 percent, compared with 43 men, or 30 percent; χ2=49.91, df=1, p<.001), particularly forced sexual assault (173 women, or 57 percent, compared with 25 men, or 17 percent; χ2=63.36, df=1, p<.001). African Americans were more likely than whites to have experienced the homicide of a family member or friend (46 African Americans, or 33 percent, compared with 56 whites, or 22 percent; χ2=6.82, df=1, p<.05). No other gender or racial differences were found.

Data from the SF-12 indicated poor physical and mental health for consumers who had been exposed to at least one type of traumatic event. Physical health functioning for these consumers was .64 standard deviation lower than general population norms, and mental health functioning was 2.5 standard deviations below the general population norms. Consumers with a history of sexual abuse (264 consumers, 55 percent) scored significantly worse on both the physical health subscale (F=4.16, df=1, 315, p<.05) and the mental health subscale (F=7.71, df=1, 315, p<.01) than consumers without a history of sexual abuse (220 consumers, 45 percent). Also, the number of lifetime traumas was negatively correlated with outcomes on both physical and mental health subscales (r=−.19, p<.001 for both subscales).

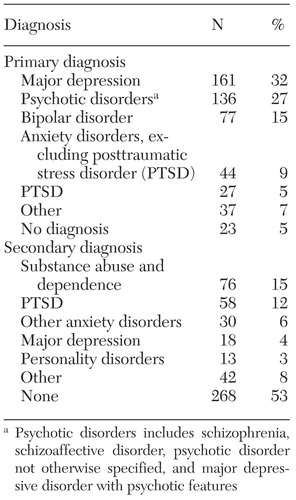

Many consumers (237 consumers, or 47 percent) received at least two diagnoses at the time of their intake interview. The most common primary and secondary diagnoses are listed in Table 2. PTSD was rarely given as a primary diagnosis (27 clients, or 6 percent); however, after substance use disorders it was the most common secondary diagnosis. The overall rate of PTSD diagnosis was 19 percent (94 clients) on the basis of the intake interview, including cases of PTSD as a tertiary diagnosis.

To determine whether PTSD recognition was enhanced by the use of the shortened TAA, we compared our results to CMHC data for the one-year period before the use of the trauma screener. Out of 6,472 consumers served at the CMHC during that period, 323 clients (5 percent) were given a diagnosis of PTSD. This indicates a substantial increase in the diagnosis during the period following the introduction of the screener. (The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, occurred midway through our data collection. In order to address potential concerns that the attacks led to an increase in PTSD diagnosis, we looked at data from the first four months of the study—May 1, 2001 to September 1, 2002—and found the rate of PTSD had already increased to 19 percent.) Chi square analyses indicated that the traumatic events most likely to lead to a clinician-assigned PTSD diagnosis were childhood sexual molestation (χ2=24.08, df=1, p<.001), forced sexual assault (χ2=38.10, df=1, p<.001), physical assault with a weapon (χ2=17.24, df=1, p<.001), physical assault without a weapon (χ2=9.97, df=1, p<.001), and witnessing traumatic events (χ2=5.98, df=1, p<.05).

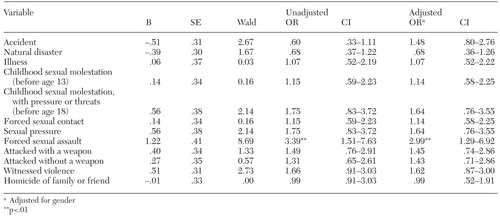

In order to investigate the types of traumatic events that were most predictive of receiving a diagnosis of PTSD, a logistic regression analysis was performed. To control for any potential confounding effects of gender or race on PTSD diagnosis, a series of hierarchical logistic regression models were carried out with gender or race entered as a first step. In the next step the traumatic events were included. Although gender initially emerged as a significant predictor of PTSD, this effect disappeared once the trauma variables were added. There was no effect of race on PTSD diagnosis; therefore, this variable was not included in the model with traumatic events. The overall model was significant at the .001 level and accounted for 22 percent of the variability in PTSD diagnosis. As shown in Table 3, the only significant predictor of PTSD was rape, when the analyses controlled for the experience of the other traumatic events.

Finally, results of the chart review were examined. The consumers randomly selected for chart review were similar to the entire sample in terms of demographic characteristics, diagnoses, and degree of comorbidity. The chart review revealed only one instance (1 percent) in which the case manager conducted a full-length TAA and completed the PTSD Checklist. However, 86 out of 97 charts (89 percent) contained intake forms indicating trauma exposure and therefore should have contained a full-length TAA and a PTSD Checklist.

The chart review also revealed a number of cases in which seemingly significant trauma details and PTSD symptoms had been reported; however, these details were not reflected in the diagnosis or treatment plan. For example, one consumer reported during the intake interview that she "continued to relive a sexual assault by her uncle [that occurred] years ago in the woods and is unable to deal with it." Her diagnosis was major depressive disorder with psychotic features. Her chart did not indicate whether her psychotic symptoms were related in content or onset to her sexual assault. Another client reported an extensive trauma history on the screener—sexual assault, physical assaults with and without weapons, and witnessing violence—and described intrusive thoughts related to these events during the interview. Her diagnosis was generalized anxiety disorder, but no attention was given in her treatment plan to her traumatic history or PTSD symptoms. These charts may not contain all information about the diagnoses that were considered and whether they were justifiably ruled out. However, if a client was given a diagnosis of PTSD, the client's treatment plan should in fact list treatment goals specific to the diagnosis. The chart review indicated that none of the clients who were given a diagnosis of PTSD had treatment plans that focused on their symptoms of PTSD.

The review of medications indicated that of the consumers who had prescriptions for medication (92 consumers, 95 percent), most had prescriptions for at least two medications (65 consumers, 67 percent). The most common medications prescribed were the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (45 consumers, or 53 percent), followed by atypical antipsychotics (38 consumers, or 45 percent), benzodiazepines (24 consumers, or 29 percent), other antidepressants (20 consumers, or 24 percent), and anticonvulsants (20 consumers, or 24 percent).

Discussion

This study revealed extremely high rates of trauma in a population of community mental health consumers. This prevalence rate of 91 percent of consumers who experienced at least one traumatic event is comparable to rates noted in previous studies (98 percent) of public mental health consumers with serious mental illness (5). Specific types of traumatic experiences, such as sexual assault, physical assault, and witnessing violence, were also quite high and consistent with previous studies (4,5). Overall, women were more likely to have experienced a sexual assault, and African Americans were more likely to have experienced the homicide of a family member or friend. These relationships have been found in other studies of clinical populations (4,5). Consistent with literature on outcomes associated with specific types of traumatic events, experiencing a sexual assault and experiencing a greater cumulative number of traumatic events were each associated with poorer health status on the SF-12 (8,14).

The rate of PTSD as a primary, secondary, or tertiary diagnosis increased from 5 percent to 19 percent following the introduction of the shortened TAA at intake. This substantial difference suggests that the shortened TAA, along with a brief PTSD symptom guide for the intake clinician, resulted in more diagnoses of PTSD. The constraints of applied research in this practice setting did not allow a standardized measure of PTSD to be included in the intake assessment. Therefore, one limitation of the study is that rates of PTSD are based on clinician-assigned diagnoses and not more objective methods of diagnosis. As a result, the 19 percent prevalence of PTSD is likely still an underestimate of the true prevalence of PTSD in this practice setting. The results of the logistic regression indicated that a history of forced sexual assault is a significant predictor of a clinician-assigned PTSD diagnosis. This finding is important in that it indicates that although clinicians are primed to detect PTSD in rape cases, they would likely benefit from additional training regarding the relationship between other traumatic events and PTSD.

For the clients who were given a diagnosis of PTSD there was little follow-up related to the diagnosis once the case was opened. Even though all case managers were instructed by their supervisors to complete the full TAA and the PTSD Checklist for all new consumers who screened positive for trauma history, the chart review indicated that this occurred in only one of the 97 cases. The chart review also revealed many clients with substantial trauma histories who reported symptoms characteristic of PTSD; yet these symptoms were not reflected in their diagnosis or treatment. In the majority of cases in which patients were given a diagnosis of PTSD, treatment focused on the other symptoms, such as psychosis or depression. These findings indicate that this CMHC population has significant trauma-related needs that are not being addressed.

Conclusion

The high rate of trauma exposure, the poor recognition of PTSD, and the success of the shortened TAA in increasing PTSD diagnosis argue for greater attention in public mental health settings to the needs of traumatized mental health consumers, as others have recommended (5,6,8). Training in the assessment and treatment of PTSD in the community mental health setting could result in significantly improved services to this population. However, future research is needed to examine existing obstacles to these services and to determine the most appropriate methods of training clinicians to conduct such work. Additional research on effective interventions for PTSD and various comorbid disorders is also needed for this population.

Dr. Cusack is affiliated with the trauma initiative department of the South Carolina Department of Mental Health, 701 East Bay Street, MSC 1110, Charleston, South Carolina 29403 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Frueh and Dr. Brady are with the department of psychiatry and behavioral services at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Dr. Frueh is also with the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Charleston.

|

Table 1. Prevalence of traumatic events among 505 community mental health center clients screened with a shortened version of the Trauma Assessment for Adultsa

a Because of missing data, the denominator used to calculate percentages may be less than 505.

|

Table 2. Most common diagnoses among 505 community mental health center clients screened for exposure to traumatic events

|

Table 3. Logistic regression to determine types of traumatic events that were predictive of receiving a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at intake among 505 community mental health center patients

1. Breslau N, Davis G, Andreski P, et al: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:216–222, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Norris FH: Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:409–418, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048–1060, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hutchings PS, Dutton MA: Sexual assault history in a community mental health center clinical population. Community Mental Health Journal 29:59–63, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mueser KT, Goodman LA, Trumbetta SL, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:493–499, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, et al: Brief screening for lifetime history of criminal victimization at mental health intake. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 4:267–277, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Craine LS, Henson CE, Colliver JA, et al: Prevalence of a history of sexual abuse among female psychiatric patients in a state hospital system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:300–304, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Kessler RC: Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(suppl 5):4–12, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

9. Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, et al: The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:427–435, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Solomon SD, Davidson JRT: Trauma: prevalence, impairment, service use, and cost. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58:5–11, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Brady K, Pearlstein T, Asnis GM, et al: Efficacy and safety of sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:1837–1844, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ: Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York, Guilford, 2000Google Scholar

13. Frueh BC, Cusack KJ, Hiers TG, et al: Improving public mental health services for trauma victims in South Carolina. Psychiatric Services 52:812–814, 2001Link, Google Scholar

14. Amaya-Jackson L, Davidson JR, Hughes DC, et al: Functional impairment and utilization of services associated with posttraumatic stress in the community. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:709–724, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Frueh BC, Cousins VC, Hiers TG, et al: The need for trauma assessment and related clinical services in a state public mental health system. Community Mental Health Journal 38:351–356, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Resnick HS: Psychometric review of Trauma Assessment for Adults (TAA), in Measurement of Stress, Trauma, and Adaptation. Edited by Stamm BH. Lutherville, Md, Sidran Press, 1996Google Scholar

17. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1995Google Scholar

18. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12): construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 32:220–233, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, et al: The PTSD Checklist: reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, Tex, 1993Google Scholar

20. Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, et al: Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behavior Research and Therapy 34:669–673, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar