Comparison of Offenders With Mental Illness Only and Offenders With Dual Diagnoses

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study compared offenders who had severe mental illness only and offenders who had severe mental illness and substance abuse problems—dual diagnoses—to determine whether these groups differed. Offenders with dual diagnoses who were involved with the criminal justice system at different levels were compared to explore their profiles and experiences after release. METHODS: Secondary data collected on offenders who had diagnoses of severe mental illness and of substance abuse in Massachusetts were used to examine sociodemographic, clinical characteristics, and criminal justice characteristics, service needs, and community reentry experiences in the first three months postrelease of 265 offenders with major mental illness and 436 with dual diagnoses. RESULTS: Offenders with dual diagnoses were more likely to be female and to have a history of being on probation and of using mental health services. On release from correctional custody, they had more immediate service needs than offenders with mental illness alone, including a need for housing and sex offender treatment, and they were more likely to require an assessment for dangerousness. They were also more likely to return to correctional custody. CONCLUSIONS: The data do not suggest that offenders with dual diagnoses have a distinct clinical background, but rather that substance abuse is an important feature that affects their real or perceived level of functioning, engagement with the criminal justice system, and dependence on social service institutions in the community.

Eighty percent (80 percent) of state inmates and 70 percent of federal inmates report substance abuse histories—alcohol or drug use disorders or both—and 50 percent of state inmates and 40 percent of federal inmates report participating in substance abuse treatment at some time in their lives (1,2). The strong association between having a substance use disorder and being incarcerated is the result of individuals coming into contact with the criminal justice system because of their direct or indirect involvement with drugs or alcohol. For instance, individuals involved with the illicit drug industry and persons who are drug addicts or public inebriates are under increased surveillance and come into contact with the criminal justice system because public intolerance and laws dictate efforts to manage them (3).

Such also seems to be the case for individuals with mental illness in the public realm. The rate of mental illness among prison inmates is four to five times higher than the rate found in the community (4,5,6). Approximately 16 percent of all state prison inmates (16 percent of all males and 24 percent of all females) have some sort of mental illness, and 10 percent of male inmates and 18 percent of female inmates have an axis I major mental disorder of thought or mood (7,8). The ability of individuals with mental illness to make rational decisions and risk-benefit calculations about criminal behavior can be compromised by their illness and, in many cases, by drug or alcohol abuse. Recent changes in policing strategies, such as community-based policing, and sentencing legislation, such as mandatory sentencing and three-strikes laws, strongly affect populations less able to manage their involvement with the illicit drug trade and their own addictions in the community (3,9,10). Therefore, criminal justice innovations and public policy mandates have brought mentally ill substance abusers—persons with dual diagnoses—into closer contact with the criminal justice system.

Nearly 80 percent of persons who have a mental illness have a co-occurring substance use disorder at some time in their lives (11,12,13). The rate of current substance abuse among persons with mental illness is about 50 percent (12,14). This rate ranges from 10 to 90 percent among mentally ill offenders (1,15,16). The wide-ranging rate reflects the various measures—screening devices, clinical interviews, and self-reports—that are used to assess substance abuse, as well as the limited availability of and opportunity to use illicit substances in some correctional facilities.

Nevertheless, almost all offenders in correctional custody return to live in the community. In studies of persons with dual diagnoses who were recently committed to the hospital from the community, Swanson, Swartz, and their colleagues (17,18,19) have found evidence of both the threat to public safety and the poor community reintegration outcomes of this patient group. Nevertheless, most studies of mentally ill individuals with a history of hospitalization use measures of community disruption and maladaptation, including violence and substance abuse (12,17,20,21,22). The effects of a substance abuse history on the outcomes of offenders with mental illness who return to the community from the criminal justice system have yet to be determined.

Do persons with mental illness involved with the criminal justice system differ from their counterparts with dual diagnoses? Are there distinct trajectories for persons with dual diagnoses who are involved to a greater or a lesser extent with the criminal justice system—for example, do those who commit felonies have outcomes different from those of misdemeanants? How do persons with dual diagnoses who have a criminal justice record navigate the community after they have been released from correctional custody? This study compared mentally ill offenders and offenders with dual diagnoses. It also documented the experience of offenders with dual diagnoses at different stages of involvement with the criminal justice system and their experiences after release.

Methods

The study used secondary program data collected in Massachusetts between 1998 and 2002 to identify offenders who had a major mental illness with or without co-occurring substance use problems (N=701). The differences between offenders with mental illness and those with dual diagnoses were examined, and data on the latter group (N=436) were analyzed to assess whether these offenders were markedly different. Demographic and clinical characteristics and experiences during community reentry were compared according to criminal history and stages of involvement in the justice system—preadjudication, misdemeanor, or felony.

Surveys of Massachusetts' prisons and county houses of corrections estimate that there are approximately 23,000 prisoners in Massachusetts—11,850 prisoners in county correctional facilities and 11,000 in state facilities—and that between 1,150 and 4,600 inmates, or 5 to 20 percent, suffer from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or another major mental illness (6,23,24). In 1998, the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health (DMH) established the forensic transition team program. The program provides tracking services for individuals eligible for DMH services. To be eligible for DMH services the individual must have a diagnosis of a major mental illness accompanied by functional impairment for a year or more. The team also provides tracking services to persons involved with the criminal justice system at the preadjudication stage, as well as transitional services for those completing misdemeanor and felony sentences and returning to communities across the state.

Persons with mental illness are identified to the forensic transition team at the preadjudication stage by mental health clinicians in the courts. After adjudication they are identified by trained correctional staff in county houses of correction and prisons. After individuals are identified as having a clinical diagnosis, they complete the DMH eligibility process that screens out individuals who do not have an axis I major mental illness. Between 1998 and 2002, the forensic transition team identified 701 persons who were eligible for DMH services—that is, they had a major axis I mental illness—who were involved with the criminal justice system. Of this group, 436 (62 percent) had dual diagnoses.

The forensic transition team program provided the data sources for the study reported here. Program data are made available for research purposes when individuals identified by the courts and corrections facilities sign a release of information administered by the forensic transition team. The release and the research and data collection processes were approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Massachusetts at Boston and the Massachusetts DMH. Program data collection instruments and the data sets used from the coded instruments for research purposes were created for this study (25).

Data collection is ongoing and includes demographic information, including age, race, gender, education, and housing status; clinical information, such as service needs and symptoms, which are categorized into symptom groups of thought, mood, or personality disorder according to the primary DSM-IV diagnosis of record; and criminal information, including the most recent offense, sex offender status, and probation or parole information. Most of the data are obtained during baseline interviews on the program intake form, after persons are found DMH eligible in courts or correctional facilities. The CAGE-ID, a section of the intake form, provides a standardized four-item screening instrument to check for a missed substance abuse history (15).

More in-depth data are collected on persons who are being released from correctional custody to the community. These data include information on community functioning and information on service needs and service engagement after release. For instance, individuals who screen positive on the CAGE-ID portion of the intake form complete a substance abuse index form with a clinician. In addition, at three months after release, a termination form is completed for persons making the transition to the community; it includes information about services and short-term postrelease outcomes.

In this study cross-tabulation and correlations were used to identify variables to include in a binary logistic regression model that compared mentally ill individuals involved with the criminal justice system and those with dual diagnoses. For individuals with dual diagnoses, postrelease criminal justice trajectories, short-term community outcomes, and level of service engagement were analyzed.

Results

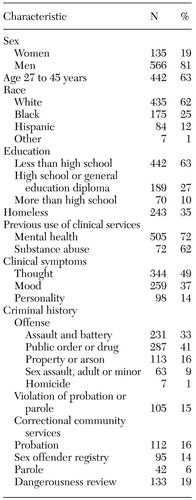

Table 1 presents data on demographic, clinical, and criminal justice variables for the 701 individuals identified as having a major mental illness of thought or mood and involved with the correctional system in Massachusetts.

Comparison of offenders

Of the 701 offenders, nearly two-thirds—436 persons or 62 percent—had dual diagnoses. The majority of the offenders with dual diagnoses were Caucasian (277 persons, or 60 percent). Most were between the ages of 27 and 45 (287 persons, or 66 percent), and most were men (366 persons, or 79 percent).

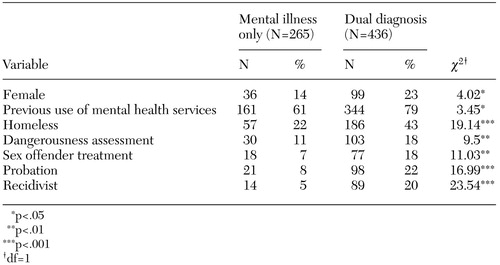

As shown in Table 2, significant differences were found between offenders with mental illness only and those with dual diagnoses in demographic characteristics, service needs, criminal histories, and short-term community outcomes. Women constituted nearly a fourth of the dual diagnosis group compared with only 14 percent of the mentally ill group. In addition, compared with the mentally ill offenders, those with dual diagnoses were significantly more likely to have a history of receiving mental health services.

A total of 243 of the 701 offenders in the sample (35 percent) anticipated that they would be homeless when they were released. Compared with the offenders with mental illness only, a significantly greater proportion of those with dual diagnoses expected to be homeless (Table 2). Few differences were found between groups in clinical disorders and symptoms. As shown in Table 1, the vast majority of the sample suffered from thought disorders, such as schizophrenia, or mood disorders, such as major depression.

As shown in Table 2, offenders with dual diagnoses were significantly more likely to have a history of probation than their mentally ill counterparts. In addition, those with dual diagnoses were more likely to repeatedly return to correctional custody. They were also disproportionately represented in the groups that required assessment for dangerousness at release and that were required to register with the sex offender registry.

When the analysis controlled for demographic, clinical, criminal history, service need, and disposition variables, 15 percent of the variance of a binary logistic regression model was explained using the Nagelkerke R2. The model results indicated that having a dual diagnosis was associated with a significantly greater likelihood of being on probation (odds ratio [OR]=1.84, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.46 to 2.22, p<.001), of being homeless (OR=2.44, CI=1.9 to 2.98, p<.001), and recidivism to the criminal justice system (OR=3.01, CI=2.41 to 3.61, p<.001). These findings suggest that without the appropriate social services, such as reentry and housing assistance, and without supports, such as treatment, most offenders with dual diagnoses, particularly those who are already under criminal justice surveillance on probation, ultimately return to correctional custody either by violating probation or committing a new crime.

Offenders with dual diagnoses

The 436 offenders with dual diagnoses were at different stages of the criminal justice system. A total of 113 were in the preadjudication stage, which means that they had been diverted to the community. A total of 192 had committed a misdemeanor, which indicates a shorter sentence—about two years—for a property or a drug-related offense. A total of 131 had committed a felony, which indicates a longer sentence—four years on average—because they had a long criminal history or had committed a person-related offense. Data on these different subgroups provided some descriptive information about crime severity as it related to trajectories after release.

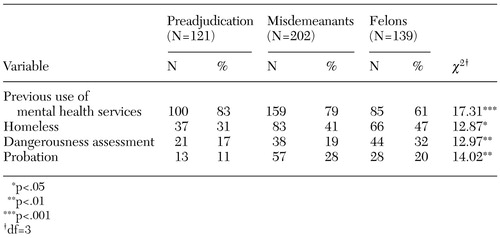

As Table 3 shows, differences were found between these three subgroups. For instance, in terms of service needs at release, nearly half of the felony subgroup anticipated being homeless. The felons also required a disproportionate number of assessments for dangerousness perhaps due to their felony status. The misdemeanants were more likely than the felons to have a history of being on probation and of receiving mental health services—services that may have helped them avoid more intensive involvement with the criminal justice system.

Nevertheless, among the offenders with mental illness and particularly among those with dual diagnoses, a "stepping-up" into the criminal justice system seemed to occur in which, for example, several adjudications for community or probation violations eventually resulted in a misdemeanor sentence. Similarly, several misdemeanor adjudications may have accumulated to a felony sentence over time.

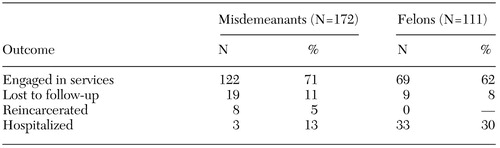

Table 4 presents three-month follow-up data on community dispositions of 283 persons with dual diagnoses who were released from correctional custody after serving either a misdemeanor sentence or a felony sentences. (The remaining 40 had not completed the three-month postrelease period.) Five categories of disposition were created: engaged in community services, lost to follow-up, immediately hospitalized or rehospitalized after a period of time in the community, and reincarcerated after a period of time in the community.

The results presented in Table 4 are not statistically significant, but they do show trends. For instance, the rates of engagement in community services, at least at the outset, were high for both the misdemeanor and felony groups, the misdemeanor group was disproportionately overrepresented in the lost-to-follow-up and reincarcerated categories. In addition, the felony group had a higher rate of hospitalization after release from prison. Thus the offenders with dual diagnoses had high rates of community engagement in the short term after release. However, given the extent of their substance abuse problems, there seemed to be incremental increases to the lost-to-follow-up, hospitalized, or reincarcerated groups over time.

Discussion

The findings from this analysis are limited because the sample included only mentally ill persons involved with the criminal justice system in Massachusetts. Although the sample is broad, it is not clinically heterogeneous in that the vast majority of offenders found eligible for DMH services in Massachusetts have severe mental illness. Because of the small number of women who had a diagnosis of a mental illness, it was not feasible to determine differences between the groups based on gender. Nevertheless, the criminal history and service differences between offenders with mental illness only and those with mental illness and substance abuse problems were found to be pronounced, and there is no reason to believe that the experiences of the offenders in this sample are not comparable to the experiences of other offenders elsewhere.

The results indicated that offenders with dual diagnoses were more likely to be serving misdemeanor sentences related to their substance use, such as probation for public disorder offenses, property crimes, and drug dealing. They were also more likely to be homeless on release from correctional custody, to have a history of probation, and to return to correctional custody after release. In addition, although the study found differences among offenders with dual diagnoses depending on the level of involvement in the criminal justice system—preadjudication, misdemeanor, and felony—the differences are attributable to the misdemeanant group's receiving more community-based mandated sentencing supports, including probation. This finding suggests that because their offenses were less serious, these offenders were more amenable to community correctional efforts, whereas felons with dual diagnoses, who were serving longer sentences and had the most diverse clinical profile, were more likely to be homeless on release. Homelessness and lack of correctional oversight could propel persons with dual diagnoses who had committed a felony into criminal activity as a survival strategy and, in turn, increase their potential for rearrest. It is somewhat counterintuitive that the felons who had dual diagnoses were more likely to be released to the community without monitoring, such as probation; however, these felons were more frequently admitted to psychiatric hospitals after release from correctional custody.

Conclusions

This study compared offenders who were mentally ill and offenders who had dual diagnoses. The results indicate that they are distinct groups in terms of criminal trajectories and service needs at release from correctional custody. Offenders with dual diagnoses are known by and involved with many systems—the mental health system, the correctional system, homeless services, and the sex offender registry. They have lengthy criminal justice and mental health service histories and immediate service needs after release from correctional custody, including a need for housing. Housing can be difficult to identify and locate, particularly for individuals who are also deemed dangerous or who are registered sex offenders.

Substance abuse among offenders with mental illness increases the likelihood of problems such as homelessness and escalating involvement with the criminal justice system. Without the appropriate social services, such as reentry and housing services, and without supports, such as treatment, offenders with dual diagnoses, particularly those already under criminal justice surveillance on probation, are highly likely to return to correctional custody either for violating probation or for a new charge. Yet, few studies have examined ex-offenders with dual diagnoses.

The double stigma of being a mentally ill substance abuser creates barriers to receiving community-based services, even when services are in place. In addition, these individuals can become involved with the criminal justice system because of the long-term course of their addiction and subsequent behaviors. Thus spending time incarcerated leaves this population with a triple stigma to contend with when they return to the community.

Nevertheless, it is important to note the patterns of postrelease service needs of offenders with dual diagnoses. Understanding these patterns facilitates the creation of a full range of appropriate services. Several studies have pointed to a range of services that might work best for persons with dual diagnoses. For instance, specialized integrated substance abuse and mental health treatment, assertive outreach, behavioral skills groups, intensive case management, transition and linking programs, and therapeutic communities are helpful to people with dual diagnoses once they have been properly identified and assessed (12,15).

However, the setting in which these individuals are originally identified and assessed is important, as is whether or not they are diverted to appropriate programs before they come to the attention of law enforcement or are too impaired or compromised to calculate the risks and benefits or the consequences of their illegal behavior. Thus substance abuse is an important feature affecting a mentally ill person's real or perceived level of functioning, engagement with the criminal justice system, and greater dependence on social service institutions in the community.

Dr. Hartwell is affiliated with the department of sociology at the University of Massachusetts at Boston, 100 Morrissey Boulevard, Boston, Massachusetts 02125 ([email protected]);.

|

Table 1. Demographic, clinical, and criminal justice characteristics of 701 mentally ill offenders

|

Table 2. Significant differences between offenders with mental illness only and those with dual diagnoses

|

Table 3. Significant differences between offenders with dual diagnoses who were diverted to the community before incarceration (preadjudication), who committed misdemeanors, and who committed felonies

|

Table 4. Outcome measures at three months after release from correctional custody among offenders with dual diagnoses who had committed misdemeanors or felonies

1. Peters RH, Hills HA: Inmates with co-occurring substance abuse and mental health disorders, in Mental Illness in America's Prisons. Edited by Steadman HJ, Cocozza JJ. Washington, DC, National Coalition for the Mentally Ill in the Criminal Justice System, 1993Google Scholar

2. Mumola C: Substance Abuse and Treatment, State And Federal Prisoners: Special Report. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999Google Scholar

3. Beckett K, Sassoon T: The Politics of Injustice: Crime and Punishment in America. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2000Google Scholar

4. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DA, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511–2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Morris SM, Steadman HJ, Veysey BM: Mental health services in United States jails: a survey of innovative practices. Criminal Justice and Behavior 24:3–19, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Rice ME, Harris GT: The treatment of mentally disordered offenders. Psychology, Public Policy, and the Law 3:126–183, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Ditton P: Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999Google Scholar

8. Pinta E: The prevalence of serious mental disorders among US prisoners, in Forensic Mental Health: Working With Offenders With Mental Illness. Edited by Landsberg G, Smiley A. Kingston, NJ, Civic Research Institute, 2001Google Scholar

9. Teplin LA, Pruett NS: Police as street corner psychiatrists: managing the mentally ill. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 15:139–156, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Green TM: Police as frontline mental health workers: the decision to arrest or refer to mental health agencies. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 20:469–486, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Weiss R: The role of psychopathology in the transition from drug use to abuse and dependence, in Vulnerability to Drug Abuse. Edited by Glantz M, Pickens R. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1992Google Scholar

12. Drake RE, Bartels SJ, Teague GM, et al: Treatment of substance abuse in severely mentally ill patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:606–611, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Wolff N, Diamond RJ, Helminiak TW: A new look at an old issue: people with mental illness and the law enforcement system. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:152–165, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17–31, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. National Gains Center: The Prevalence of Co-occurring Mental and Substance Abuse Disorders in the Criminal Justice System. Washington, DC, National Institute of Corrections, 1997Google Scholar

16. Chiles JA, Von Cleve E, Jemelka RP, et al: Substance abuse and psychiatric disorders in prison inmates. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1132–1134, 1991Google Scholar

17. Swanson J, Borum R, Swartz M: Psychotic symptoms and disorders and the risk of violent behavior in the community. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health 6:317–338, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Swanson J, Borum R, Swartz M, et al: Violent behavior preceding hospitalization among persons with severe mental illness. Law and Human Behavior 23:185–204, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, et al: Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce hospital recidivism? Findings from a randomized trial with severely mentally ill individuals. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1968–1975, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

20. Fulwiler C, Grossman H, Forbes C, et al: Early onset substance abuse and community violence by outpatients with chronic mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 48:1181–1185, 1997Google Scholar

21. Luettgen J, Chrapko WE, Reddon JR: Preventing violent re-offending in not criminally responsible patients: an evaluation of a continuity treatment program. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 21:89–98, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Satsumi Y, Inada T, Yamauch T: Criminal offenses among discharged mentally ill individuals: determinants of the duration of discharge and absence of diagnostic specificity. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 21:197–207, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Fisher W, Packer I, Simon L, et al: Community mental health services and the prevalence of severe mental illness in local jails: are they related? Administration and Policy in Mental Health 27:371–382, 2000Google Scholar

24. Lamb RH, Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483–492, 1998Link, Google Scholar

25. Hartwell, SW, Orr, K: The Massachusetts forensic transition team for mentally ill offenders reentering the community. Psychiatric Services 50:1220–1222, 1999Link, Google Scholar