Factors Related to Psychiatric Hospital Readmission Among Children and Adolescents in State Custody

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined factors related to psychiatric hospital readmission among children and adolescents who were wards of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. METHODS: The authors analyzed service reports and clinical ratings on the Childhood Severity of Psychiatric Illness (CSPI) for 500 randomly selected children and adolescents who underwent psychiatric hospitalization. Children who were readmitted to the hospital within three months of discharge from the index hospitalization were compared with those who were not readmitted in terms of preadmission factors, clinical characteristics at the index hospitalization, services in the hospital, and posthospital services. RESULTS: The children who were readmitted were rated as more learning disabled or developmentally delayed and had received fewer posthospital service hours than the children who were not readmitted. The highest rates of readmission were found among children who lived in congregate care settings before the index hospitalization and those who lived in a rural region. CONCLUSIONS: The findings of this study highlight the significance of enabling factors, notably living arrangement, geographic region, and posthospital services, for children and adolescents in the child welfare system. Prevention of readmission among these children must focus on community-based services.

The role of psychiatric hospitals has shifted dramatically (1,2). Inpatient programs are now focused on acute stabilization, leaving most treatment to community-based providers (3). Despite briefer stays, hospitalization remains a high-cost component of the mental health service system, accounting for about 70 percent of all dollars spent on mental health care in the past decade (4).

Since the dramatic decline in long-term hospitalizations and the reductions in and closures of state-operated hospitals, readmission rates have increased (5,6,7). Explanations for these higher readmission rates have varied. Some authors have proposed that the increase is a result of deinstitutionalization and the failure of community mental health reforms (7). Others view readmission as a failure of the previous hospital admission, implying that readmission is a result of shortened inpatient stays (8,9,10,11,12,13). However, a prospective study of hospital readmission found neither poor hospital outcome nor premature discharge to be a risk factor for readmission (14). Finally, some authors conceive of acute hospital care as an appropriate short-term crisis intervention that can be used periodically during episodes of acute illness among persons with persistent psychiatric illness (15,16,17). Although return to the hospital is not necessarily an indicator of poor hospital outcome, it is generally seen as an undesirable outcome for a system of care (14). Reducing readmission rates is viewed as a quality improvement goal.

Most research on readmission has centered on characteristics of the patient. Clinical factors—such as diagnoses of schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, affective and personality disorders, and substance abuse as well as medication noncompliance, violent or criminal behavior, age at onset of illness, and history of hospitalizations—have been reported to be associated with readmission (9,10,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31). Studies have explored service delivery factors and have had mixed findings on the impact of access to aftercare and use of outpatient services on risk of readmission (12,13,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39).

Most readmission studies have used adult samples. However, psychiatric disorders are reported to occur among 20 percent of children aged nine to 17 years (40,41). Hospitals continue to play a significant role in the children's mental health service system, despite an increase in the use of community services in the past decade (42). Psychiatric hospitalizations account for almost half the money spent on adolescent mental health care (43). Hospitals are the most intensive, restrictive, and structured environments for children and adolescents, and research has shown that 40 percent of hospital placements of children may be avoidable (43,44) and, in some cases, traumatic to the child or his or her family (2,45).

Children in the child welfare system constitute a particularly high-risk population in terms of mental health need (43,46,47). Evidence suggests that the prevalence of serious emotional disorders is higher in this group of children (48,49). This finding is understandable considering the circumstances that lead to state intervention (50,51,52). For children who are in state custody, psychiatric hospitalization often serves as a transition between placements (43,53). Thus factors other than clinical needs—for example, need for a new placement—may especially affect the use of inpatient psychiatric services for children who are wards of the state.

In this study we investigated the clinical characteristics and environmental and service delivery factors related to readmission in a sample of children who were wards in a large Midwestern state—Illinois. The purpose of the study was to identify differences in clinical and environmental factors between the children who were readmitted and those who were not.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted through the Screening, Assessment, and Supportive Service (SASS) program of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. The SASS program, implemented in 1992, provides crisis assessment and treatment services to children in protective custody who are referred for or are at risk of hospitalization for psychiatric problems (46). SASS services include ongoing monitoring of children who require acute psychiatric inpatient care, deflection services for children who do not meet admission criteria, and posthospitalization services (46,54).

The SASS program serves children and adolescents throughout Illinois. Cook County includes Chicago and is the most highly populated county in Illinois and the most racially and economically diverse. Northern Illinois is primarily suburban, is less racially diverse, and has a lower poverty rate. Central Illinois, composed of rural and suburban areas and primarily white, is known to have the most sophisticated community services. Southern Illinois, also primarily white, is a rural region with fewer community services and a high poverty rate.

Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained through Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Informed consent was not necessary, because permission was obtained from the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services to conduct the retrospective analyses.

Sample

The sample was taken from a database that contained complete information on at least one episode of treatment—that is, provision of services by SASS—for 1,275 children and adolescents in the custody of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services who received SASS services between July 1999 and June 2000. The 843 total psychiatric hospitalizations in this data file involved 576 individual children. The sample consisted of 500 randomly selected children who had been hospitalized in any psychiatric facility—267 boys, 232 girls, and one child for whom information on gender was missing—ranging in age from three to 21 years.

Measures

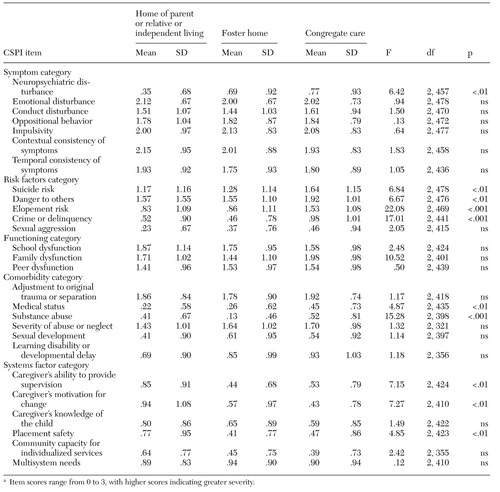

Data were collected from monthly SASS reports, which include information on demographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnosis, prescreening living arrangement, SASS service hours, and duration of hospital stay. Another source of data was the Childhood Severity of Psychiatric Illness (CSPI), a standardized assessment tool completed by SASS workers at the time of screening. The CSPI is a 27-item Likert-type rating scale with four anchored levels per item, from 0, no evidence of disturbance, through 3, an acute or severe degree of disturbance (2,55). The CSPI items are listed in Table 1, sorted by impairment category. Results from pilot studies suggest that the CSPI can serve as a useful decision-support tool and an accurate measure of children's mental health needs, use of mental health services, and outcome (2). The CSPI has been shown to have an interrater reliability range of .70 to .80, based on the Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ) (46). In this study, CSPI ratings were examined to assess the type and level of the children's mental health needs, as documented by SASS workers during the screening that led to the index hospitalization (56).

Procedures

Records of monthly SASS reports completed for each child in the sample were examined to determine which children had been rehospitalized within three months of discharge from the index hospitalization. Of the total sample, 385 children (77 percent) had not been readmitted and 107 (21 percent) had been readmitted; records were missing for eight children (2 percent).

Statistical analyses were conducted by using SPSS 10.0 to compare the children who were readmitted with those who were not in terms of preadmission factors, clinical characteristics at the index hospitalization, services in the hospital, and posthospital services provided by SASS. Because of missing data, not all statistics are based on the total sample.

Results

Preadmission factors

An independent-sample t test indicated an association between age at admission to index hospitalization and readmission that approached significance (t=1.74, df=490, p<.10). The children who were readmitted tended to be older than those who were not readmitted (mean±SD age of 13.52±3.25 years compared with 12.85±3.64 years).

Forty-nine (21 percent) of the girls and 58 (22 percent) of the boys were readmitted. A Pearson chi square test indicated that this difference was not statistically significant. Sixty-two (19 percent) of the 330 children who lived in Cook County, nine (22 percent) of the 41 children who lived in Northern Illinois, 18 (25 percent) of the 72 children who lived in Central Illinois, and 11 (41 percent) of the 27 children who lived in Southern Illinois were readmitted. Pearson chi square tests indicated that, compared with other regions, Southern Illinois, a rural area, had a significantly higher readmission rate (χ2=6.5, df=3, p<.05, N=470) and Cook County had a significantly lower rate (χ2=4.1, df=3, p<.05, N=470).

To study the effect of living arrangement, we grouped the children into three categories based on their living arrangement before the index hospitalization: the home of a parent or relative or independent living; a foster home; or a congregate care setting (a residential treatment center, a group home, a youth emergency shelter, or institutional corrections). Eleven (13 percent) of the 82 children and adolescents who lived with a parent or relative or independently, 39 (19 percent) of the 204 children who lived in a foster home, and 52 (27 percent) of the 191 children who lived in a congregate care setting were readmitted. Pearson chi square tests indicated that children who lived in congregate care had a significantly higher rate of readmission than those who lived in other settings (χ2=6.5, df=2, p<.05, N=477). These effect sizes were comparable in different regions; the effect was most pronounced in Central Illinois (χ2=4.1, df=2, p<.05, N=69).

An analysis of variance indicated that the children who lived in congregate care had significantly higher ratings on a number of CSPI variables. The results are summarized in Table 1. Even when the differences in CSPI ratings were controlled for, the children in congregate care still had a significantly higher rate of readmission (Wald statistic=7.83, df=1, p<.005).

Clinical characteristics at the index hospitalization

The two groups of children were compared on each of the 27 CSPI items and the five categories that comprise them. The only statistically significant difference between the two groups was in the presence of learning disability or developmental delay; the children who were readmitted were rated as more learning disabled or developmentally delayed than those who were not readmitted (mean score of 1.24±1.06 compared with .76±.95; t=3.76, df=121.05, p<.001).

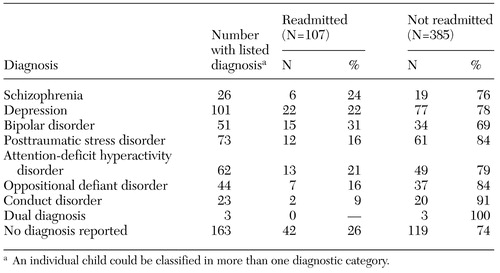

We also studied psychiatric diagnosis to determine whether the groups differed in terms of clinical characteristics at the index admission. The DSM-IV diagnoses of the children, as recorded on the monthly reports by SASS workers, were categorized into eight diagnostic groups: schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and dual diagnosis. The results are summarized in Table 2. Pearson chi square tests revealed no statistically significant relationships between readmission status and any of the diagnostic categories.

Services in the hospital

With regard to duration of the index hospital stay, an independent-sample t test indicated that the children who were readmitted (mean length of stay of 28.05±35.16 days) did not significantly differ from those who were not readmitted. An independent-sample t test also showed that the children who were readmitted did not significantly differ from those who were not in terms of hospital service hours provided by SASS workers—for example, monitoring of hospital treatment and discharge planning (4.9±10 compared with 3.88±4.6 hours).

Posthospital services

An independent-sample t test indicated that children who were not readmitted tended to have received more service hours after the index admission—for example, case management—from SASS workers than did readmitted children (4.94±8.18 compared with 3.47±4.18 hours; t=−2.12, df=276.33, p<.05). Given the age differences between groups, an analysis of covariance was conducted, controlling for age. This analysis also showed that the children who were readmitted received fewer posthospital service hours.

Discussion

The results of this study can be conceptualized in terms of Andersen and Newman's (57) model of access to medical care with attention to predisposing, enabling, and need factors. The predisposing characteristics of the sample that were examined—age and sex—were not significantly related to readmission. For the most part, neither were need characteristics or illness level as assessed by the CSPI and psychiatric diagnostic information. The only clinical variable that differed between the children who were readmitted and those who were not was the presence of a learning disability or developmental delay—the children who were readmitted were more likely to have mild mental retardation than those who were not readmitted. Conceivably, the community mental health service system—which can be conceptualized as an enabling component—is ill equipped to meet the special needs of children with below average intellectual functioning or developmental delays.

Enabling factors, on the other hand, had notable relationships with readmission. Geographic region, living arrangement, and posthospital service hours significantly differentiated children who were readmitted from those who were not. More than a quarter of the children in congregate care were readmitted, compared with about one in five of those in foster care and one in eight of those who were living with parents, relatives, or independently. Conceptualized in terms of the vulnerability-stress model of serious mental illness (58,59), children in congregate care—who are vulnerable to mental illness—encounter significant stress in living away from their families and in being surrounded by other troubled children. Dincin and Witheridge (34) found that a higher level of life event stress is associated with relapse.

Another possible explanation for the higher rate of readmission among children in congregate care is that such settings have a lower threshold for hospitalizing children, perhaps as a means of preventing further disruption or to minimize liability. Leon and colleagues (60) found that a significant number of children who were referred for psychiatric hospitalization from residential treatment centers did not meet the clinically appropriate threshold for a psychiatric hospital admission according to the CSPI. A low threshold for readmission—or for hospitalization in general—of children in congregate care may also be due in part to the potential lack of a familial connection in residential settings compared with homes of biological parents, relatives, or foster parents.

We observed notable case-mix differences among hospitalized children who came from different living arrangements. As indicated by past research on clinical characteristics of children in residential settings, the children in this study who were in congregate care tended to have higher CSPI ratings (greater severity) for neuropsychiatric disturbance, risk behaviors, and caregiver characteristics than children who had other living arrangements (60,61,62). Thus, even among hospitalized children, those in congregate care represent a population with greater needs than children living in the community.

More than two-fifths of the children and adolescents who lived in Southern Illinois were readmitted, compared with about one in four in Central Illinois and one in five in Northern Illinois and Cook County. These results suggest that regional variations in practice style or access to community services may influence readmission rates. Southern Illinois has fewer community services, and obtaining existing services often requires significant travel time. Researchers have demonstrated differences in psychiatric hospitalization rates between rural and urban settings. For example, Anderson and Estle (63) found that a disproportionate number of children from rural counties compared with urban counties were admitted to inpatient care and resided in areas in which there were shortages of mental health and primary care professionals. The difference in readmission rates between children in congregate care and those who had other living arrangements was most pronounced in Central Illinois, where community services are the most sophisticated. Thus children who live in the community rather than in congregate care may have greater access to these community services.

Finally, the children who were not readmitted received more posthospital service hours from SASS after discharge from the index hospitalization than did those who were readmitted. This finding suggests that posthospitalization services are an important enabling factor in preventing rehospitalization, perhaps by maintaining stabilization attained during hospitalization. Our findings are consistent with those of others who have attested to the benefits of continued outpatient care (38,64,65) and of appropriate discharge planning and follow-up visits (3,13) for recently hospitalized patients. Results from our study contrast with other results that suggest that aftercare services may not influence the likelihood of readmission (13,31,35,36,). However, these other studies did not examine children in the child welfare system—a high-risk, special-needs population that may have a particular need for community services to maintain stabilization and prevent relapse.

The design of this study precluded causal conclusions. Only associations between readmission and nonclinical factors have been established. Also, because the data on hundreds of children were collected by multiple workers in the field, problems with inaccurate information and missing data were inevitable. Finally, the study was conducted in one state that has a unique system of services, and the sample was made up of children in the child welfare system. Thus the findings may have limited generalizability.

Conclusions

Findings from this study indicate the significant association between enabling characteristics, chiefly environmental and service delivery factors, and readmission of children and adolescents in the child welfare system. A better understanding of the use of psychiatric hospitalization by various residential settings and in different regions is essential. Greater access to sophisticated mental health services for children in residential treatment as well as improved crisis intervention in congregate care settings should reduce the risk of readmission. Conceivably, an examination of the sophisticated and comprehensive community services found in certain regions can inform efforts to improve service systems in other geographic areas.

Future research on mental health services must examine the quality and effectiveness of services, particularly posthospitalization services and services geared toward children who have special needs. Services other than those provided firsthand by crisis programs, such as psychotherapy and family therapy, along with activities not traditionally considered mental health services, also should be considered. Psychiatric hospitalization is likely to continue to be important as a means of short-term crisis intervention and stabilization. Efforts to maintain gains achieved during hospitalization, through comprehensive discharge planning, follow-up visits, and maintenance of medication compliance, are crucial in preventing readmission.

The results of this study support an environment-specific psychosocial approach to understanding the mental health needs of children and adolescents in the child welfare system. Such an approach must take into account environmental or service delivery factors in addition to clinical characteristics in order to tailor a system of care that meets the needs of its most vulnerable.

Acknowledgments

Ms. Romansky wrote this article as part of the senior honors program of the School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and through a National Research Service Award Fellowship from the Institute for Health Services Research and Policy Studies at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. Financial support for this study was provided by the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. The authors thank Bruce Briscoe, B.A., and Dan A. Lewis, Ph.D.

The authors are affiliated with the mental health services and policy program of the division of psychology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Abbott Hall, Room 1205, 710 North Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60611 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Childhood Severity of Psychiatric Illness (CSPI) scores of children and adolescents in state custody, by living arrangementa

a Item scores range from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater severity.

|

Table 2. Children and adolescents in state custody who were readmitted to a psychiatric hospital and those who were not readmitted, by psychiatric diagnosis

1. Geller JL: The last half-century of psychiatric services as reflected in Psychiatric Services. Psychiatric Services 51:41-67, 2000Link, Google Scholar

2. Lyons JS, Howard KI, O'Mahoney MT, et al: The Measurement and Management of Clinical Outcomes in Mental Health. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

3. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL: Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatric Services 51:885-889, 2000Link, Google Scholar

4. Redick RW, Witkin MJ, Atay JE, et al: Highlights of organized mental health services in 1992 and major national and state trends, in Mental Health, United States, 1996. DHHS pub (SMA) 96-3098. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996Google Scholar

5. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al: Predicting the "revolving door" phenomenon among patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856-861, 1995Link, Google Scholar

6. Nierman P, Lyons JS: State mental health policy: shifting resources to the community: closing the Illinois State Psychiatric Hospital for Adolescents in Chicago. Psychiatric Services 52:1157-1159, 2001Link, Google Scholar

7. Lurigio AJ, Lewis DA: Worlds that fail: a longitudinal study of urban mental patients. Journal of Social Issues 45:79-90, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Appleby L, Desai PN, Luchins DJ, et al: Length of stay and recidivism in schizophrenia: a study of public psychiatric hospital patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:72-76, 1993Link, Google Scholar

9. Geller JL: In again, out again: preliminary evaluation of a state hospital's "worst" recidivists. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:386-390, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Carpenter MD, Mulligan JC, Bader IA, et al: Multiple admissions to an urban psychiatric center: a comparative study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:1305-1308, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Gastal FL, Andreoli SB, Quintana MI, et al: Predicting the revolving door phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, affective disorders and non-organic psychoses. Revista de Saude Publica 34:280-285, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Heggestad T: Operating conditions of psychiatric hospitals and early readmission: effects of high patient turnover. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 103:196-202, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lien L: Are readmission rates influenced by how psychiatric services are organized? Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 56:23-28, 2002Google Scholar

14. Lyons JS, O'Mahoney MT, Miller SI, et al: Predicting readmission to the psychiatric hospital in a managed care environment: implications for quality indicators. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:337-340, 1997Link, Google Scholar

15. Bryson KK, Naqvi A, Callahan P, et al: Brief Admission Program: an alliance of inpatient care and outpatient case management. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 28:19-23, 1990Google Scholar

16. Dott SG, Walling DP, Bishop SL, et al: The efficacy of short-term treatment for improving quality of life. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 184:507-509, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Yu-Chin R, Arcuni OJ: Short-term hospitalization for suicidal patients within a crisis intervention service. General Hospital Psychiatry 12:153-158, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Appleby L, Luchins DJ, Desai PN, et al: Length of inpatient stay and recidivism among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:985-990, 1996Link, Google Scholar

19. Casper ES, Donaldson B: Subgroups in the population of frequent users of inpatient services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:189-191, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

20. Casper ES, Regan JR: Reasons for admission among six profile subgroups of recidivists of inpatient services. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 38:657-661, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Craig TJ, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, et al: Rapid versus delayed readmission in first-admission psychosis: quality indicators for managed care? Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 12:233-238, 2000Google Scholar

22. Green JH: Frequent rehospitalization and noncompliance with treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:963-966, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Harris M, Bergman HC, Bachrach LL: Psychiatric and nonpsychiatric indicators for rehospitalization in a chronic patient population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:630-631, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Hodgson RE, Lewis M, Boardman AP: Prediction of readmission to acute psychiatric units. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:304-309, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lewis T, Joyce PR: The new revolving-door patients: results from a national cohort of first admissions. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 82:130-135, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kastrup M: The use of a psychiatric register in predicting the outcome "revolving door patient": a nation-wide cohort of first time admitted psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 76:552-560, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Korkeila JA, Lehtinen V, Tuori T, et al: Frequently hospitalized psychiatric patients: a study of predictive factors. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:528-534, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Postrado LT, Lehman AF: Quality of life and clinical predictors of rehospitalization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:1161-1165, 1995Link, Google Scholar

29. Sanguineti VR, Samuel SE, Schwartz SL et al: Retrospective study of 2,200 involuntary psychiatric admissions and readmissions. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:392-396, 1996Link, Google Scholar

30. Schalock RL, Touchstone F: A multivariate analysis of mental hospital recidivism. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:358-367, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Sullivan G, Wells KB, Morgenstern H, et al: Identifying modifiable risk factors for rehospitalization: a case-control study of seriously mentally ill persons in Mississippi. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1749-1756, 1995Link, Google Scholar

32. Coursey RD, Ward-Alexander L, Katz B: Cost-effectiveness of providing insurance benefits for posthospital psychiatric halfway house stays. American Psychologist 45:1118-1126, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. D'Ercole A, Struening E, Curtis JL, et al: Effects of diagnosis, demographic characteristics, and case management on rehospitalization. Psychiatric Services 48:682-688, 1997Link, Google Scholar

34. Dincin J, Witheridge TF: Psychiatric rehabilitation as a deterrent to recidivism. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:645-650, 1982Abstract, Google Scholar

35. Fisher WH, Geller JL, Altaffer F, et al: The relationship between community resources and state hospital recidivism. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:385-390, 1992Link, Google Scholar

36. Foster EM: Do aftercare services reduce inpatient psychiatric readmissions? Health Services Research 34:715-736, 1999Google Scholar

37. Hawthorne WB, Green EE, Lohr JB, et al: Comparison of outcomes of acute care in short-term residential treatment and psychiatric hospital settings. Psychiatric Services 50:401-406, 1999Link, Google Scholar

38. Huff ED: Outpatient utilization patterns and quality outcomes after first acute episode of mental health hospitalization: is some better than none, and is more service associated with better outcomes? Evaluation and the Health Professions 23:441-456, 2000Google Scholar

39. Solomon P, Davis J, Gordon B: Discharged state hospital patients' characteristics and use of aftercare: effect on community tenure. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:1566-1570, 1984Link, Google Scholar

40. Friedman RM, Katz-Leavy JW, Manderscheid RW, et al: Prevalence of serious emotional disturbance in children and adolescents, in Mental Health, United States, 1996. DHHS pub (SMA) 96-3098. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996Google Scholar

41. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, et al: The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:865-877, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Pires SA, Stroul BA, Armstrong MI: Health Care Reform Tracking Project: Tracking State Health Care Reforms As They Affect Children and Adolescents With Behavioral Health Disorders and Their Families:1999 Impact Analysis. Tampa, Fla, Department of Child and Family Studies, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, 2000Google Scholar

43. Collins BG, Collins TM: Child and adolescent mental health: building a system of care. Journal of Counseling and Development 72:239-243, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

44. Knitzer J: Unclaimed Children. Washington, DC, Children's Defense Fund, 1982Google Scholar

45. Knitzer J: Mental health services to children and adolescents: a national view of public policies. American Psychologist 38:905-911, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

46. Leon SC, Uziel-Miller ND, Lyons JS, et al: Psychiatric hospital service utilization of children and adolescents in state custody. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:305-310, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Simms MD, Freundlich M, Battistelli ES, et al: Delivering health care and mental health care services to children in family foster care after welfare and health care reform. Child Welfare 78:166-183, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

48. Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40:409-418, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Pilowsky D: Psychopathology among children placed in family foster care. Psychiatric Services 46:906-910, 1995Link, Google Scholar

50. Parker KC, Forrest D: Attachment disorder: an emerging concern for school counselors. Elementary School Guidance and Counseling 27:209-215, 1993Google Scholar

51. Pecora P J: Investigating allegations of child maltreatment: the strengths and limitations of current risk assessment systems. Child and Youth Services 15:73-92, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

52. Roys P: Ethnic minorities and the child welfare system. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 30:102-118, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Kiesler CA: Mental health policy and the psychiatric inpatient care of children: implications for families, in When There's No Place Like Home: Options for Children Living Apart From Their Natural Families. Edited by Blancher J. Baltimore, Md, Brooks, 1994Google Scholar

54. Lyons JS, Kisiel CL, Dulcan M, et al: Crisis assessment and psychiatric hospitalization of children and adolescents in state custody. Journal of Child and Family Studies 6:311-320, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

55. Lyons JS: Severity of Psychiatric Illness Scale-Child and Adolescent Version. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1998Google Scholar

56. Lyons JS, Uziel-Miller ND, Reyes F, et al: Strengths of children and adolescents in residential settings: prevalence and associations with psychopathology and discharge placement. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:176-181, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Andersen R, Newman JF: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly Journal 51:95-124, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Myin-Germeys I, van Os J, Schwartz JE, et al: Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:1137-1144, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME: A heuristic vulnerability/stress model of schizophrenic episodes. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:300-312, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Leon SC, Lyons JS, Uziel-Miller ND, et al: Evaluating the use of psychiatric hospitalization by residential treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:1496-1501, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

61. Lyons JS, Libman-Mintzer LN, Kisiel CL, et al: Understanding the mental health needs of children and adolescents in residential treatment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 29:582-587, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

62. Lyons JS, Schaefer K: Mental health and dangerousness: characteristics and outcomes of children and adolescents in residential placements. Journal of Child and Family Studies 9:67-73, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

63. Anderson RL, Estle G: Predicting level of mental health care among children served in a rural delivery system in a rural state. Journal of Rural Health 17:259-265, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Goodpastor WA, Hare BK: Factors associated with multiple readmissions to an urban public psychiatric hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:85-87, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

65. Solomon P, Evans D, Delaney MA: Community service utilization by youths hospitalized in a state psychiatric facility. Community Mental Health Journal 29:333-346, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar