State Mental Health Policy: Shifting Resources to the Community: Closing the Illinois State Psychiatric Hospital for Adolescents in Chicago

Since deinstitutionalization, the reapportionment of mental health services from large state-operated facilities into community-based programs has evolved unsteadily. In the past decade, the census of state hospitals has shrunk to the point that closing these facilities has become a viable option (1). A number of closures have occurred in recent years, and the majority have involved hospitals that served adults with severe and persistent mental illness (2,3). No closures of state-operated facilities for children have been discussed in the mental health services literature. This paper details a three-year process of ending the involvement of the Illinois state government in the direct provision of inpatient care to children and adolescents in the Chicago area.

Several challenges have been identified as barriers to the successful closure of state facilities (4,5,6). Clinical considerations include whether sufficient community treatment alternatives exist to address the needs of persons who were formerly treated at the state hospital (4). Decisions about employment and human resource allocation must address potentially broad implications for labor when a facility is closed (5). Finally, the transition of the physical plant from a hospital to its next use must be considered (6). Each of these concerns must be addressed in a coordinated fashion.

Background and history

In 1993 the state of Illinois operated two inpatient facilities for adolescents in Chicago: the Illinois State Psychiatric Institute (ISPI) and the Henry Horner Children's Center (HHCC). These facilities had a total of seven 15- to 20-bed units, for a total capacity of 120 beds; HHCC also had a 15-bed unit for children under 12 years of age.

Patients who were referred to ISPI were generally involved with foster care or correctional services or had experienced treatment failures in other settings. The number of admissions was low, but the lengths of stay were long. A unit that specialized in the long-term treatment of children who had severe trauma-related illness averaged four to six admissions a year, with an average length of stay of two years.

HHCC admitted 225 youths in 1993, including 42 children under the age of 12. The layout of the hospital's sprawling campus, with widely dispersed cottages and a centrally located school, hampered security efforts and resulted in many elopements each year. Youth gang activities and other safety concerns hindered clinical efforts at HHCC and created significant public pressure for reform. Clinical investigations and administrative audits of the hospital eventually led to litigation.

On July 29, 1994, in accordance with a federal class action lawsuit, A. N. v. Patla, a consent decree was executed in which the Illinois Department of Mental Health agreed to implement specific reforms to improve the quality of mental health care for children receiving public funds in the Chicago area. The state was required to develop an implementation plan to specify how it would meet the requirements of the decree. Both ISPI and HHCC were covered by the decree. The administrative structures of ISPI and HHCC were combined to form Metropolitan Child and Adolescent Services (Metro C&A), and a team headed by a child and adolescent psychiatrist was appointed to address the tenets of the consent decree.

After the administrative integration had occurred, HHCC units were closed and integrated into the ISPI site. With this accomplished, the state was able to abandon the difficult-to-manage campus-style hospital. During this transition, Metro C&A leadership made efforts to effect an institutional cultural change by shifting the clinical focus from long-term care to an acute care model that had more community and family involvement. The hospital consolidation was followed by a quality-improvement process that focused on breaking down boundaries between hospital- and community-based treatment.

In December 1995 administrative roles and responsibilities were reorganized. State hospital facility directors became regional network managers who assumed responsibility for monitoring grant-in-aid community mental health agencies on a geographic basis in addition to overseeing the operations at the state hospital. This shift represented a major transition from a facility-based administrative organization toward one with broader system-of-care responsibilities. This strategy reduced the amount of regional resources and funding that specific facilities received from state agencies.

The leadership team that had been appointed to respond to the consent decree began discussions about the possibility of closing the Metro C&A inpatient facility in mid-1996. The appeal of the idea was that it had the potential to reduce expenditures on inpatient care, to enable families to receive care closer to their homes, to allow the redirection of resources into community-based services, and to transfer accountability for clinical care from state employees to contracted private hospitals and clinicians. The closure was announced in March 1997.

The announcement marked the beginning of a public debate on the appropriateness of the closing. Opposition to the closure from hospital employees was almost immediate. However, this opposition was managed by ensuring that all union employees were allowed to transfer to a remaining state facility for persons with psychiatric or developmental disabilities. Nonunion staff were provided with state-funded positions elsewhere. The only opposition expressed by consumers was that of one family whose child had received services at ISPI. The family's efforts drew modest media attention.

The difficult media questions that were put to the architects of the closure created a helpful public dialogue on how the state hospital's services would now be offered by some of the area's finest hospitals. In helping to address this specific family's needs and through the raising of concerns by other stakeholders and advocates, the credibility of the planning group was secured, and opposition to the closure waned. The significant concurrent reinvestment in community-based services was a powerful tool for gaining the support of important public advocates.

The physical plant that housed ISPI is adjacent to the campus of the University of Illinois at Chicago. The university was interested in acquiring the hospital building to meet a growing demand for space. The transfer of the facility from the State Office of Mental Health to the university was seamless and enabled the building to be retained for public use.

The impact of the closure of the state hospital was evaluated in several ways. The first question was that of the effect the closure would have on hospital use and on institutionalization. To address this question, overall hospital use was studied by determining the number of admissions, lengths of stay, and readmission rates. Discharge disposition—to home or to extended residential treatment—was also monitored.

A second question was whether the network hospitals served the most challenging children and adolescents. To address this question, Child Behavior Checklists (7) were completed for 69 cases on admission to the state hospital in the previous year of its operation, for 226 cases on admission to network hospitals during the first year of privatization, and for 216 cases on admission to network hospitals during the second year of privatization.

Findings

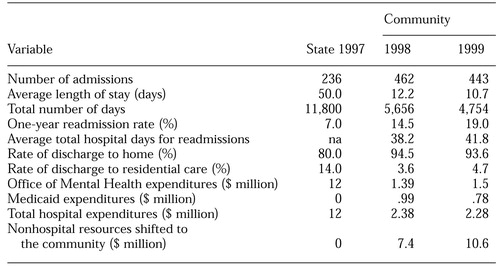

Table 1 presents data on the admissions, length of stay, readmission rates, and discharges to home and residential treatment for the state hospital in 1997 and the community network hospitals in 1998 and 1999. The overall expenditures for each year by the Office of Mental Health and Medicaid are included.

Figure 1 presents a comparison of the aggregated scores on the Child Behavior Checklist at admission for children who were hospitalized in the state hospital before its closure and a sample of children who were hospitalized in the community network hospitals during the first and second years after privatization. The figure shows that the children who were hospitalized after the closure were clinically comparable to those treated in the state hospital.

Discussion

On the basis of anecdotal information and empirical data, it appears that the closure of the state hospital for children and adolescents in Chicago was achieved without undue burden on those it served. Although the number of hospital admissions increased, the average number of days declined dramatically, by more than 75 percent. In addition, the community linkage appears to have improved in that the rate of residential placements also declined dramatically, from 14 percent of discharges at the state hospital in 1997 to fewer than 5 percent from private hospitals in 1998 and 1999. The actual numbers of children who were transferred from the hospital to residential treatment declined from 33 in 1997 to 16 in 1998 and 20 in 1999.

The closure resulted in a dramatic reduction in expenditures on hospital services, from $12 million in 1997 to about a fifth of that amount in 1998 and 1999. More than $10 million was garnered for annual expenditure on other approaches to serving children and families. The promise by state leaders to invest savings from the closure into building community-based services was a key aspect of the success of this process. Although the closure was accomplished during an economic boom, when less emphasis was placed on cost containment, there is always the risk that funds saved in a state system will be lost to priorities other than mental health care.

The privatization of hospital services appears to have produced an increase in the number of readmissions. However, part of this increase reflects readmission of discharged children who otherwise would have remained hospitalized all year. With extended stays, the number of readmissions is kept artificially low. For the population of children and adolescents who were rehospitalized within six months in private-sector hospitals, the average total number of hospital days was still significantly lower than the average length of stay for all hospitalized adolescents at the state hospital in 1997 (50 days in 1997 compared with 38.2 days in 1998 and 41.8 days in 1999). However, beyond this reduction it appears that readmission within a year is more common under privatization. This finding suggests that it is important to continue development of community-based services that can effectively serve the youths who are likely to return to the hospital.

Closure of any existing program or facility faces many obstacles. A goal to convert investment in human and physical infrastructure into a more flexible resource can enliven the natural resistance to change. The state of Illinois was able to achieve its objective by capitalizing on an already shifting service system that was rendering the state hospital increasingly obsolete. Also helping to pave the way was an inclusive planning process to address the very real concerns of clinical staff, advocates, and families. The result has been greater funding of community-based mental health services without sacrificing access to high-quality psychiatric hospital care.

Dr. Nierman is affiliated with the Illinois Office of Mental Health and with the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois, 4200 North Oak Park Avenue, Annex, Chicago, Illinois 60634 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Lyons is affiliated with the mental health services and policy program of Northwestern University in Chicago. Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., and Colette Croze, M.S.W., are editors of this column.

Figure 1"Aggregated scores on the Child Behavior Checklist at admission for children who were hospitalized in the state hospital before its closure and children who were hospitalized in community network hospitals during the first and second years after privatization1

1 Higher scores indicate more serious problems.

|

Table 1. Data on hospitalizations and expenditures for state and community network hospitals in Chicago

1. Dorwart RA, Schlesinger M, Davidson H, et al: A national study of psychiatric hospital care. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:204-210, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Wright ER, Avirappattu G, Lafuze JE: The family experience of deinstitutionalization: insights from the closing of Central State Hospital. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 26:289-304, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Pescosolido BA, Wright ER, Kikuzawa S: "Stakeholder" attitudes over time toward the closing of a state hospital. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:318-328, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Rothbard AB, Kuno E, Schinnar AP, et al: Service utilization and costs of community care for discharged state hospital patients: a 3-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:920-927, 1999Link, Google Scholar

5. Mesch DJ, McGrew JH, Pescosolido BA, et al: The effects of hospital closure on mental health workers: an overview of employment, mental and physical health, and attitudinal outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:305-317, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wright ER: Fiscal outcomes of the closing of Central State Hospital: an analysis of the costs to state government. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:262-275, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, Vt, University of Vermont, 1983Google Scholar