Staff Members' Emotional Reactions to Aggressive and Suicidal Behavior of Inpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the relationship between the characteristics of inpatients and staff members' emotional reactions to the patients, particularly the extent to which the reactions were related to patients' aggressive or suicidal behavior. METHODS: The Feeling Word Checklist-58 was used to measure staff members' feelings. Two positive and five negative feeling dimensions were examined: important, confident, rejected, on guard, bored, overwhelmed, and inadequate. A total of 253 staff members from a wide variety of psychiatric wards at a university-affiliated hospital in Oslo, Norway, completed a total of 2,473 checklists about their emotional reactions to 207 patients. For each patient, a member of the research team used information from ward staff who knew the patient to complete a Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale measuring whether the patient had been aggressive (outward aggression) or suicidal (inward aggression). RESULTS: Staff reported positive feelings about patients much more frequently than negative feelings. Multiple regression analysis revealed that patient characteristics explained much more of the variance in negative feelings than in positive feelings. Outward aggression explained an average of 22 percent of the variance in scores on the five negative dimensions. Inward aggression explained an average of 12 percent more of the variance in scores on the five negative dimensions. Gender, age, amount of medication, and diagnosis (psychotic or not psychotic) explained only a small proportion of the variance in feeling scores. CONCLUSIONS: Even though the level of negative feelings toward patients was low, patients' aggressive and suicidal behavior explained a large proportion of the variance in negative feelings.

Probably no group of inpatients evokes stronger emotional reactions among staff members than those who display violent or suicidal behavior (1). Some studies have described how violent patients can evoke fear and anger among staff members and how such emotional reactions may complicate treatment by causing splitting and disagreement among team members if the reactions are not recognized (2,3,4). Staff may avoid the fear they feel toward aggressive patients by being passive, becoming preoccupied with minor individual needs, and focusing on a scapegoat (5). Focusing on staff members' emotional reactions may facilitate intervention and treatment planning by providing the treatment team with useful information about the kinds of problems patients are struggling with (6,7,8) and may thereby prevent violent and aggressive behavior (9,10,11).

Clinical studies point out the importance of creating milieus that give staff members the opportunity to express and share their emotional reactions to suicidal patients (12). Unrecognized negative emotional reactions of members of the treatment team may blind them to the suicidal potential of a patient, which may ultimately contribute to the patient's suicide (13,14).

The studies cited above are mainly theoretical. Except for some studies of the frequency of patients' violent behavior (15,16), there is a striking paucity of empirical studies. In particular, studies are lacking on the potential impact of aggressive and suicidal behaviors on staff members.

Lanza (17) examined 40 nursing staff members' reactions to their experiences of being physically assaulted by patients. A large number of staff reported no emotional reaction. Because the study was retrospective, suppression and denial may explain these findings. However, in another study by Lanza (18), nearly three-quarters of a sample of 99 registered nurses said that they thought victims of an assault would experience a fairly severe or very severe emotional reaction (18). Other studies have found that staff members who have been assaulted by patients experience symptoms of posttraumatic stress (19,20). The discrepant findings are most likely attributable to the fact that some staff members were asked about assaults to themselves, some about assaults to others, and some about hypothetical assaults.

To our knowledge, only one study has empirically examined the relationship between staff members' emotional reactions and aggressive behavior other than physical assaults. Colson and associates (21) examined the relationship between staff members' emotional reactions and four "treatment difficulty" factors that were developed in a previous study (22): withdrawn psychoticism, character pathology, violence-agitation, and suicidal-depressed behavior. The study was conducted on long-term wards, and the staff members' emotional reactions were rated on a Feeling Word Checklist comprising 16 items. Violent and aggressive behavior was related to different emotional dimensions depending on the professional discipline of the staff member. Among psychiatrists and activity therapists, suicidal-depressed behavior did not correlate significantly with any of the feeling dimensions, but among nurses and social workers suicidal-depressed behavior had a weak significant correlation with both positive and negative feelings.

We conducted searches on MEDLINE for 1966 to 2002 and on PsycINFO for all years indexed in that database by using combinations of words for emotional reactions, such as "countertransference" and "emotion," with words for staff members, such as "nursing staff" and "therapists." No additional studies were found. Thus there is an obvious need for more comprehensive studies of staff members' emotional reactions to patients who display aggressive or suicidal behavior. Such studies should employ instruments that cover a wide range of feelings and that are able to discriminate among nuances of feelings that these behaviors may elicit among staff. It is equally important to obtain data on patient characteristics, such as age, gender, severity of illness, diagnosis, and medication, and to use a well-established instrument that measures suicidal and aggressive behavior. The data should be collected from a variety of psychiatric wards and should include patients suffering from a broad range of mental disorders.

We undertook such an investigation to answer three questions. In the absence of violent or aggressive behavior, how are gender, age, medication dosage, and a diagnosis in the psychotic spectrum related to staff members' emotional reactions to patients? How much additional variance in emotional reactions does violent or suicidal behavior explain? Does any interaction between patient characteristics contribute significantly to the explained variance?

Methods

During May 1999, we collected data from 17 different psychiatric wards at Ullevaal University Hospital in Oslo, Norway. The hospital's catchment area consists of both urban and suburban areas and serves 195,000 inhabitants. A total of 231 beds are on the 17 wards, and approximately 1,100 patients are treated each year. The chairman of the regional ethical committee approved the study.

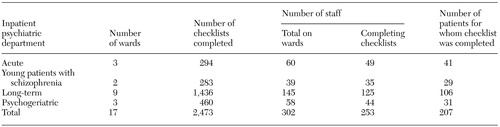

Table 1 lists the psychiatric departments that participated in the study along with the number of wards, patients, and staff members who completed the Feeling Word Checklist with 58 feeling words (FWC-58) and an estimate of the total number of staff eligible to complete the FWC-58. The three acute psychiatric wards were similar in structure, function, and patient characteristics. These wards were responsible for all psychiatric emergencies in the hospital's catchment area. The department for young patients with schizophrenia had two similar wards that specialized in treating patients who were younger than 30 years who had a diagnosis in the schizophrenia spectrum.

The long-term inpatient department comprised six long-term wards and three intermediate wards. Two of the intermediate wards were open, and one was locked; four of the long-term wards were locked, and two were open. Most patients on these wards had chronic psychosis or a severe personality disturbance. One of the three psychogeriatric wards provided long-term inpatient treatment, the second treated patients with functional psychiatric disorders, and the third treated patients with combined organic and functional psychiatric disorders.

The staff members were from various disciplines and included physicians, psychologists, nurses, and aides. Those who completed the form were required to be in daily contact with patients. Only the night staff was excluded from the study. Most of the staff members who volunteered to complete the form were nurses and aides. To ensure staff anonymity and to facilitate greater honesty, the staff members gave no information about themselves. In completing the checklist, they were instructed not to describe their emotional reactions to one specific conversation with a patient but to describe their overall feelings about the patient during their most recent conversations. Each staff member was required to complete at least five checklists for five different patients. All patients on all wards were included, except for a few who had been admitted for less than five days.

The amount of medication was calculated by using defined daily doses (DDDs) (23). The DDD represents the recommended average daily dosage of a drug and is defined as one haloperidol equivalent (8 mg). A DDD between zero and .50 was scored as 1, between .51 and 1.00 as 2, between 1.01 and 1.50 as 3, and so on. Separate scores were calculated for antipsychotics, antidepressants, and sedatives. A total medication score was calculated as the sum of the three scores.

To measure the emotional reactions of staff members to patients, we used the FWC-58. The psychometric properties of the FWC-58 were evaluated in a previous study (24). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0, not at all, to 4, very much. In the previous study, we constructed subscales for seven dimensions of feeling based on a factor analysis with Varimax rotation. The two positive dimensions were important (empathic, caring, and enthusiastic) and confident (relaxed, objective, and calm). The five negative dimensions were rejected (disliked, disparaged, and stupid), on guard (anxious, cautious, and threatened), bored (aloof, indifferent, and empty), overwhelmed (surprised, confused, and invaded), and inadequate (sad, distressed, and helpless).

For each patient for whom a FWC-58 was received, the first author completed the Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale (SDAS) with information obtained from the ward nurse in charge and a nurse or aides from the ward milieu who both had good knowledge about the patient's behavior and attitude. The SDAS comprises 11 items; two items measure inward-directed aggression (suicidal behavior), and nine items measure outward-directed aggression. The interobserver reliability of the SDAS has been found to be adequate (25). Staff members who completed the FWC-58 were blind to the SDAS scores.

Correlations between variables were calculated as Pearson product-moment coefficients. To estimate how much of the variance each of the patient variables explained, we used a blockwise multiple hierarchic regression analysis for each of the seven feeling dimensions. Age and gender were entered in the first block, because these two variables must be considered the most basic ones. Diagnosis was a dichotomous variable (psychosis present or absent) and was entered along with the amount of medication in the second block as a measure of severity of illness. By entering the inward-aggression subscale score in the third block, we controlled for the amount of variance explained by the variables in the two first blocks. Finally, we entered the outward-aggression subscale score, which we considered to be the most important variable.

Scores on the five negative feeling subscales were skewed, with mean scores of less than 1. The SDAS scores were also highly skewed. However, the normal P-P plots of standardized residuals were normally distributed for the dependent variables. Inspection of scatterplots showed that none of the patients' scores were outliers, indicating that the statistical method used in this study is adequate.

Results

As shown in Table 1, a total of 253 staff members completed 2,473 checklists for 207 patients—102 men and 105 women. During the study period, a total of 218 patients were treated on the study wards. Eleven patients were excluded from the study because they had been admitted for less than five days.

The mean±SD age of the patients was 45±19 years. Of the 207 patients, 65 (80 percent) had a diagnosis in the psychotic spectrum: schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, or affective psychosis. The mean medication score was 4.5±2.7.

Overall, the staff members reported feeling significantly more important and confident than rejected, bored, on guard, overwhelmed, or inadequate. The mean scores on the FWC-58 subscales were 1.50±.40 for important and 2.16±.33 for confident, compared with .40±.32 for rejected, .73±.44 for on guard, .50±.35 for bored, .55±.35 for overwhelmed, and .79±.45 for inadequate. However, aggressive and suicidal behaviors were strongly related to the degree of negative feelings.

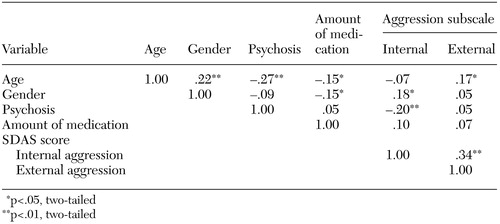

The mean score on the SDAS outward-aggression subscale was 9±7.4. The score on the inward-aggression subscale was .9±1.5. Table 2 lists the intercorrelations between the different patient characteristics and these subscale scores.

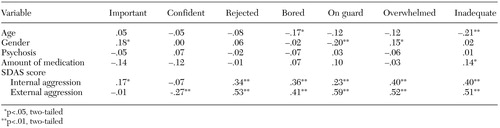

Correlations between the patient variables and the seven feeling dimensions are shown in Table 3. Strong positive correlations were found between both the outward- and the inward-aggression subscale scores and scores on the five negative feeling dimensions. A fairly strong negative correlation was found between the outward-aggression subscale score and the confident dimension.

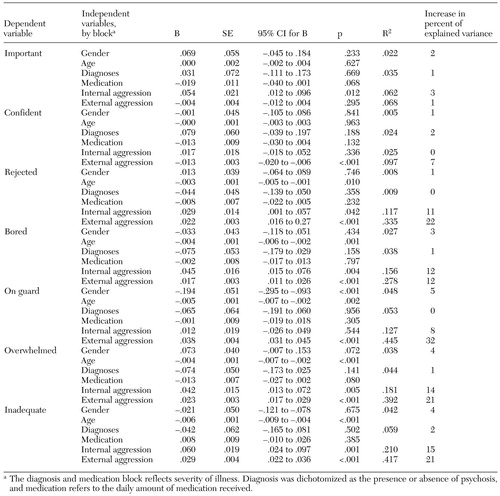

Results from the blockwise multiple hierarchic regression analysis are shown in Table 4. Age and gender (block 1) explained a small but significant proportion of the variance in three feeling dimensions: on guard, 5 percent; overwhelmed, 4 percent; and inadequate, 4 percent. Illness severity (block 2) did not explain a significant amount of the variance in any dimension.

When age, gender, and illness severity were controlled for, the SDAS scores still explained a large and significant proportion of the variance in the scores on the five negative dimensions but only a small proportion of variance in the scores on the two positive dimensions. The inward-aggression score (block 3) explained about 12 percent of the variance in scores on the five negative dimensions, and the outward-aggression score explained about 22 percent of the variance in these dimensions. The outward-aggression score explained the most variance in the on guard dimension (32 percent) and the least variance in the bored dimension (12 percent).

Because significant interactions were found between age, gender, and SDAS scores, the analyses were repeated separately for men and women and for patients younger and older than 40 years (median, 41 years). For one feeling dimension—important—there was a clear interaction between gender and inward aggression. Whereas inward aggression explained a significant proportion (6 percent) of the variance in this dimension for women patients, the amount explained for the men was nonsignificant (1 percent). That is, a higher level of suicidality among women patients seemed to elicit stronger feelings among staff members of being important.

For three subscales—on guard, overwhelmed, and inadequate—a significant interaction was noted between gender and outward aggression. For the on guard and inadequate dimensions, outward aggression explained more of the variance among men (45 percent and 22 percent, respectively) than among women (19 percent and 14 percent). For the overwhelmed dimension, this finding was reversed: outward aggression explained more of the variance among women (24 percent) than men (15 percent). A higher level of outward aggression among men seemed to elicit stronger feelings of being on guard and inadequate. In addition, the staff members reported feeling more overwhelmed when women displayed aggressive behavior than when men did so.

We also found a significant interaction between age and SDAS scores for two feeling dimensions. For the inadequate dimension, outward aggression explained more of the variance for patients older than 40 years (37 percent) than for those 40 years and younger (7 percent). For the rejected dimension, the same pattern was found for the two age groups: outward aggression explained 8 percent of the variance among older patients and 36 percent among younger patients. For the rejected dimension, the opposite pattern was found: outward aggression explained 18 percent of the variance among older patients and 6 percent of the variance among younger patients.

These findings seem to indicate that staff members felt more rejected and inadequate when older patients displayed aggressive behavior than when younger patients did so. Suicidal behavior appeared to evoke stronger feelings of being rejected when it occurred among younger patients.

Discussion

We found that certain patient characteristics explained a large proportion of the variation in staff members' negative feelings about patients but only a small proportion of the variation in positive feelings. Aggressive and suicidal behaviors were the two characteristics that most strongly accounted for the variation in negative feelings.

Although both suicidal and aggressive behaviors evoked negative emotions among staff members, aggressive behavior was more strongly associated with negative feelings than was suicidal behavior. It is logical and understandable that patients whose aggression is directed toward others appear to elicit stronger feelings of being anxious, insecure, rejected, and confused than patients whose aggression is directed toward themselves. These findings support previous observations that staff members are more likely to accept suicidal and self-mutilating behaviors than aggressive behavior (2).

Colson and colleagues (21) found few negative emotional reactions among staff members toward patients who displayed suicidal behavior. Our findings are somewhat different. Even when we controlled for outwardly aggressive behavior, suicidal behavior explained about 12 percent of the variance in staff members' negative feelings toward patients. The difference may be due to several factors. Most important, we controlled for patient characteristics, such as gender and age, and we used an instrument with an extensive list of feeling descriptors.

Suicidal behavior appears to elicit mostly negative feelings among staff members, and it is important to be aware of these emotional reactions. If not acknowledged and properly handled, such negative feelings may lead to premature discharge of suicidal patients, justified by statements such as "he is not really suicidal" or "she is just manipulating." An important task for staff members is to contain and work through negative feelings toward patients.

The amount of medication a patient was receiving and the patient's diagnosis explained only a small proportion of the variation in staff members' positive and negative feelings. We used a dichotomous variable for diagnosis—whether or not a patient had a psychotic-spectrum disorder. Use of more differentiated diagnostic variables would have permitted a closer examination of the explained variance. However, this study used diagnosis as a measure of severity of illness. It was not designed to examine the degree to which different diagnoses contribute to staff members' feelings toward patients.

By themselves, age and gender did not contribute much to the variation in staff members' feelings toward patients. However, the picture was more complicated because age and gender interacted with other patient characteristics in ways that significantly contributed to such variation. Therefore, data were analyzed separately for women and men and for younger and older patients. For men and women who displayed the same level of violent and aggressive behaviors, staff members reported stronger feelings of being on guard and inadequate in regard to men and stronger overwhelmed feelings in regard to women. This finding is probably attributable to the fact that men are physically stronger than most women and therefore elicit stronger feelings of being anxious, insecure, and threatened. In this regard it is interesting that previous studies have found that staff members seem to underestimate the risk of violence among women and overestimate the risk among men (26,27).

Staff members in this study also reported stronger feelings of being rejected and inadequate when patients were older (over 40 years old), even when these patients displayed the same level of aggressive behavior as younger patients. It is easy to imagine that older people who exhibit such behavior challenge cultural stereotypes: older people are not supposed to display aggressive behavior, and, if they do, they elicit staff members' feelings of being rejected and inadequate.

Colson and associates (21) found that different types of patient behaviors elicited different emotional reactions among different types of staff. It would be interesting to examine these differences further. However, we consulted staff members about how best to facilitate honesty in their reports of feelings toward patients, and we decided that the reports should be anonymous. Therefore, we had no personal information about staff.

As noted above, the distribution of the subscale scores was skewed. It could be argued that the negative emotions reported by staff members were weak and that strong positive feelings overshadowed the negative feelings. All studies that have used detailed instruments like the Feeling Word Checklist to capture staff members' emotional reactions to patients have noted skewed scores (24,28,29,30). There may be several reasons for this finding. First, people may tend to focus on positive feelings—hospital staff members in particular. People probably choose to work in hospitals in order to help others, and they probably feel confident about their ability to do so, which presents the possibility of response bias. Staff members probably think that they are supposed to feel helpful and confident and that they are not supposed to express negative feelings. However, even though the mean scores on the negative feeling dimensions were low, aggressive and suicidal behavior explained a large proportion of the variance in these scores.

One limitation of the study was that staff were not required to complete the FWC-58, which may have biased our results

However, 84 percent of the staff did in fact complete the checklists. We have no reason to believe that the checklist ratings of staff who did not participate in the study would have been significantly different than the ratings of those who did. However, even if there was a difference, it would probably not have been large enough to influence the overall results. Although staff could select any patients to complete the checklist for, almost all patients included in the study were rated by at least ten staff members, which reduced the possibility of selection bias.

In a classic paper called "The Ailment," published in 1957, Main (31) stated, "In a human relationship the study of one person, no matter which one, is likely to throw light on the behavior of the other." Forty years later, Spielman (32) noted that clinical experience has underlined the importance of Main's observation. Previous studies have shown how suicidal and aggressive behaviors create emotional burdens for hospital staff (1,4,5,13). Our study has attempted to further explore how the behaviors of patients affect the emotions of staff.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Odd Aalen, Ph.D., for help with data analysis.

Dr. Rossberg is a research fellow and Dr. Friis is research director in the department for research and education of the psychiatric division at Ullevaal University Hospital, N-0407 Oslo, Norway (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Friis is also professor of psychiatry at the University of Oslo.

|

Table 1. Inpatient wards participating in a study of staff members' emotional reactions to patients' aggressive and suicidal behavior

|

Table 2. Correlations between patient characteristics and scores on the internal and external aggression subscales of the Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale (SDAS)

|

Table 3. Correlations between patient characteristics, scores on the internal and external aggression subscales of the Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale (SDAS), and scores on the seven dimensions of the Feeling Word Checklist-58

|

Table 4. Blockwise multiple regression analysis of the relationship between patient characteristics and scores on the seven dimensions of the Feeling Word Checklist-58

1. Cooper C: Patient suicide and assault: their impact on psychiatric hospital staff. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 33:26–29, 1995Google Scholar

2. Lion J, Pasternak S: Countertransference reactions to violent patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 130:207–210, 1973Link, Google Scholar

3. Maier G, Van-Rybroek G: Managing countertransference reactions to aggressive patients, in Patient Violence and the Clinician. Edited by Hartwig AC, Eichelman BS. American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

4. Stamm I: Countertransference in hospital treatment: basic concepts and paradigms. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 49:432–450, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

5. Cornfield RB, Fielding SD: Impact of the threatening patient on ward communications. American Journal of Psychiatry 137:616–619, 1980Link, Google Scholar

6. Dubin WR: The role of fantasies, countertransference, and psychological defenses in patient violence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1280–1283, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Harty M: Countertransference patterns in the psychiatric treatment team. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 43:105–122, 1979Medline, Google Scholar

8. Miles MW: The evolution of countertransference and its applicability to nursing. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 29:13–20, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Felthouse AR: Preventing assaults on a psychiatric inpatient ward. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:1223–1226, 1984Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Flannery RB, Hanson MA, Penk WE, et al: Replicated declines in assault rates after implementation of the assaulted staff action program. Psychiatric Services 49:241–243, 1998Link, Google Scholar

11. Maier GJ, Stava LJ, Morrow BR, et al: A model for understanding and managing cycles of aggression among psychiatric inpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:520–524, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Modestin J: Countertransference reactions contributing to completed suicide. British Journal of Medical Psychology 60:379–385, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Maltsberger JT, Buie DH: Countertransference hate in the treatment of suicidal patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 30:625–633, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lorentzen S, Island TK, Friis S, et al: The UllevÅl acute-ward follow-up study: reflections on the treatment of psychotic patients who committed suicide. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 49:5–10, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Lehmann LS, McCormick RA, Kizer KW: A survey of assaultive behavior in Veterans Health Administration facilities. Psychiatric Services 50:384–389, 1999Link, Google Scholar

16. Owen C, Tarantello C, Jones M, et al: Violence and aggression in psychiatric units. Psychiatric Services 49:1452–1457, 1998Link, Google Scholar

17. Lanza ML: The reactions of nursing staff to physical assault by a patient. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:44–47, 1983Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Lanza ML: A follow-up study of nurses' reactions to physical assault. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:492–494, 1984Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Erdos BZ, Hughes DH: A review of assaults by patients against staff at psychiatric emergency centers. Psychiatric Services 52:1175–1177, 2001Link, Google Scholar

20. Matthews LR: Effect of stress debriefing on posttraumatic stress symptoms after assaults by community housing residents. Psychiatric Services 49:207–212, 1998Link, Google Scholar

21. Colson DB, Allen JG, Coyne L, et al: An anatomy of countertransference: staff reactions to difficult psychiatric hospital patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:923–928, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

22. Colson DB, Allen JG, Coyne L, et al: Patterns of staff perception of difficult patients in a long-term psychiatric hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:168–172, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

23. World Health Organization's Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology: Guidelines for ATC Classification and DDD Assignment. Oslo, Norway, World Health Organization, 1995Google Scholar

24. Rossberg JI, Hoffart A, Friis S: Psychiatric staff members' emotional reactions toward patients: a psychometric evaluation of an extended version of the Feeling Word Checklist (FWC-58). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 57:45–53, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Wistedt B, Rasmussen A, Pedersen L, et al: The development of an observer-scale for measuring social dysfunction and aggression. Pharmacopsychiatry 23:249–252, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Lam JN, McNiel DE, Binder RL: The relationship between patients' gender and violence leading to staff injuries. Psychiatric Services 51:1167–1170, 2000Link, Google Scholar

27. McNiel DE, Binder RL. Correlates of accuracy in the assessment of psychiatric patients' risk of violence. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:901–906, 1995Link, Google Scholar

28. McWhyte CR, Constantopoulos C, Bevans HG: Types of countertransference identified by Q-analysis. British Journal of Medical Psychology 55:187–201, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Holmqvist R, Armelius B-Å: Emotional reactions to psychiatric patients: analysis of a feeling checklist. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 90:204–209, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Hoffart A, Friis S: Therapists' emotional reactions to anxious inpatients during integrated behavioral-psychodynamic treatment: a psychometric evaluation of a feeling word checklist. Psychotherapy Research 10:462–473, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Main TF: The ailment. British Journal of Medical Psychology 30:129–145, 1957Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Spielman R: "The ailment," by TF Main:40 years on. Therapeutic Communities 19:221–226, 1998Google Scholar