Race, Age, and Back Pain as Factors in Completion of Residential Substance Abuse Treatment by Veterans

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Variables associated with successful completion of residential substance abuse treatment were identified. METHODS: The records of 340 veterans admitted to a 120-day substance abuse treatment program were retrospectively analyzed. The likelihood of successful treatment completion was calculated as a function of race, age, gender, psychiatric diagnosis, past suicide attempts, homelessness, legal history, childhood physical or sexual abuse, parental history of addiction, multiple substance dependence, medical problems, and the race of the therapist. Univariate analysis and logistic regression analysis were used to identify variables that were significant predictors of treatment completion. RESULTS: Overall, 66 percent of veterans completed the program. Eighty-two percent of the veterans admitted to the program were black, and 16 percent were white. The completion rate of black veterans (71 percent) was significantly higher than that of white veterans (49 percent). Veterans completing treatment were significantly more likely to be older, by an average of two years, than those who did not complete treatment. The association between younger age and failure to complete the program was largely accounted for by younger black veterans. Veterans with back pain were significantly less likely to complete treatment than those without back pain. Completion rates did not vary by the other variables examined. In the regression analysis that included age, race, and back pain, each variable, when adjusted by the other variables, was a significant predictor of completion. CONCLUSIONS: White patients were less likely to complete residential substance abuse treatment in a program in which the majority of both therapists and patients were black. Younger black veterans and those with back pain were also less likely to complete treatment.

The success of residential substance abuse treatment is believed to be related to completion of the treatment program. Thus a number of investigators have studied factors associated with completion of treatment. Race, age, gender, psychiatric diagnosis, homelessness, legal involvement, a childhood history of physical or sexual abuse, and multiple substance dependencies have all been reported to affect treatment outcomes or rates of graduation from treatment programs (1,2,3,4,5,6,7).

Research has shown that older individuals are more likely to complete treatment (4,5). Other studies have found that females receive treatment less frequently and that even when they are treated, they are less likely to successfully complete treatment (1,4,8,9,10). Some studies have reported that a comorbid psychiatric disorder is negatively associated with successful treatment completion (3,5,11,12,13), whereas other studies have found that psychiatric comorbidity is not a factor affecting completion (14,15,16).

Childhood physical and sexual abuse is an infrequently studied variable in the residential substance abuse treatment setting. Because childhood abuse is associated with substance abuse, major depression, and poor treatment outcomes among women, its prevalence and association with outcome have been examined in female treatment populations (7,17). The transmission of substance dependence in families has been described, but the relationship between treatment completion and a family history of substance dependence is unclear (18,19).

Among patients with known substance abuse, treatment is further complicated by chronic pain because these patients are often dependent on narcotic analgesics (20). The relationship between back pain and residential treatment outcomes is unknown.

The examination of race as a variable affecting treatment completion requires special attention (21). In some research, race has been used as a biological construct (22). The results of studies of the association between race and successful completion of treatment are somewhat contradictory. Although several studies have reported that individuals who belong to racial and ethnic minority groups are less likely to successfully complete residential treatment programs (23,24,25,26), others have not found race to be a factor (27,28,29).

Some have argued that completion of treatment does not depend on whether an individual is a member of an ethnic or racial minority group in the population at large, but instead that it depends on whether he or she is a member of a minority group within the treatment setting (29,30). The role of the race of the therapist has been examined in some studies (31,32,33), but no studies have looked at this factor in residential treatment.

In a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study of treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in a community setting, pairing of black patients with white clinicians was associated with early dropout and with receiving less intensive services (32). In another study, black veterans reported more sobriety when treated in programs with higher proportions of black veterans, and white veterans reported more sobriety in treatment programs with lower proportions of black veterans (29).

Clinicians in the drug and alcohol program of the Hampton VA Medical Center in Hampton, Virginia, retrospectively reviewed the records of all veterans admitted in 1996. The program is a domiciliary-based residential treatment program with an average daily census of 90 and an average length of stay of approximately 120 days. Participants have access to a variety of substance abuse treatment services and vocational rehabilitative services. The program maintains a zero tolerance for relapse.

The purpose of the study reported here was to determine whether specific variables were associated with successful completion of residential treatment. The variables were race, age, gender, psychiatric diagnosis, past suicide attempts, homelessness on admission, legal history, childhood physical or sexual abuse, parental history of addiction, multiple substance dependencies, medical problems, and the therapist's race.

Methods

Data on 1996 admissions to the drug and alcohol program of the Hampton VA Medical Center were gathered over a six-month period from late 1998 until early 1999. A total of 340 patients were admitted in 1996.

The likelihood of successful completion was analyzed as a function of race, age, gender, psychiatric diagnosis, past suicide attempts, homelessness on admission, legal history, childhood physical or sexual abuse, parental history of addiction, multiple substance dependencies, medical problems, and the therapist's race. Age was analyzed by an unpaired t test. All other variables were analyzed by contingency table analysis (chi square). Logistic regression was used for the multivariate analysis of variables that were significant predictors of successful completion in a univariate analysis.

Results

Subjects' characteristics

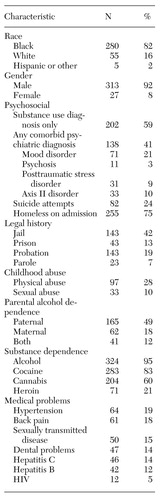

The average age of veterans on admission to the program was 41.7±6.9 years, with a range of 25 to 71 years. Most of the veterans were between the ages of 35 and 45. As shown in Table 1, 92 percent of the 340 veterans were men, and 8 percent were women. Eighty-two percent identified themselves as black, 16 percent as white, and 2 percent as Hispanic or other.

Forty-one percent had a dual diagnosis of a significant axis I or axis II disorder in addition to their substance dependence disorder. Twenty-one percent had a mood disorder. Only 3 percent had a primary psychotic disorder. Nine percent had posttraumatic stress disorder, and 10 percent had a personality disorder. Twenty-four percent of the veterans reported a history of suicide attempts. Any psychiatric disorder diagnosed for 2 percent or less of the sample was excluded from the analyses.

At admission, 75 percent of the veterans reported that they were homeless. Forty-two percent had been jailed, and 13 percent had been imprisoned. Nineteen percent were on probation, and 7 percent were on parole. Twenty-eight percent had a childhood history of physical abuse, and 10 percent had a childhood history of sexual abuse.

Forty-nine percent of the sample reported a paternal history of alcohol dependence, and 18 percent reported a maternal history of alcohol dependence; 12 percent reported both a paternal and a maternal history. Ninety-five percent met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence. Eighty-three percent were diagnosed as having cocaine dependence, and 60 percent were dependent on cannabis. Twenty-one percent had a diagnosis of heroin dependence.

Many of the veterans reported physical problems. Nineteen percent suffered from hypertension, 18 percent complained of back pain, 15 percent had sexually transmitted diseases, 14 percent had dental problems, 14 percent tested positive for hepatitis C, 12 percent had been exposed to hepatitis B, and an additional 5 percent were HIV positive.

Completion rates

Overall, 225 of the 340 veterans (66 percent) successfully completed the program. A total of 106 (31 percent) failed to do so, and nine (3 percent) had other dispositions, such as transfer to other programs. These nine patients were excluded from further analysis.

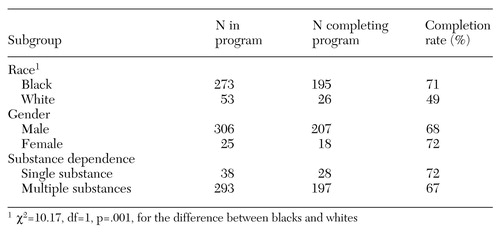

As Table 2 shows, 71 percent of black veterans completed treatment, compared with 49 percent of white veterans, a statistically significant difference. Seventy-two percent of the women in the program and 68 percent of the men completed treatment, not a statistically significant difference. Veterans who were dependent on a single substance were no more likely to complete treatment than those dependent on multiple substances.

Veterans who successfully completed the program were two years older on average than those who failed to complete it (mean±SD ages of 42.4±6.7 years and 40.3±7.3 years; t= 2.53, df=329, p= .012). A significant interaction between age and race was found in predicting treatment completion (χ2=6.37, df=1, p<.012).

Black veterans were on average two years younger than white veterans (mean±SD ages of 41.3±6.8 and 43.3±7.6 years; t=1.99, df=333, p= .047). The mean±SD age of black veterans who did not complete the program was 38.9±6.8, whereas the mean age of white veterans who did not complete the program was 44±7.5 years. Thus the association between younger age and failure to complete the program was largely accounted for by younger black veterans.

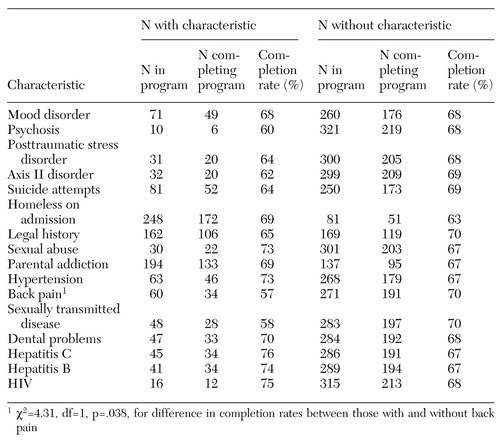

As shown in Table 3, no association was found between treatment completion and psychiatric diagnosis, history of suicide attempts, or childhood physical or sexual abuse. Homelessness, while prevalent (75 percent), was not associated with treatment completion. Legal problems, including a history of incarceration or current parole or probation, were also not associated with completion. In addition, no association was found for a parental history of addiction. Table 3 also summarizes the association between medical problems and completion rates. Only back pain was associated with a lower likelihood of treatment completion (χ2=4.31, df=1, p=.038).

Race of the therapist

The race of the therapist was not significantly associated with treatment completion. A total of 141 of the 206 patients with black therapists completed the program, for a success rate of 68 percent. Forty-four of the 68 patients with white therapists completed treatment, for a success rate of 65 percent. Fifty-six patients had a Native American therapist, and 41 completed treatment, for a success rate of 73 percent.

Comparison of completion rates by the race of the patient with the race of the therapist indicated that regardless of whether the therapist was black or white, black veterans were more likely to complete treatment than whites. Among the 170 black patients who had a black therapist, 121 (71 percent) completed the program. Among the 33 white patients who had a black therapist, 17 (51 percent) completed treatment. Among the 56 black patients who had a white therapist, 40 (71 percent) completed treatment. Among the 11 white patients who had a white therapist, three (27 percent) completed treatment. For the Native American therapist, the success rates by race were more nearly equal. Thirty-four of the 46 black patients (74 percent) who were treated by this therapist completed the program, compared with six of the nine white patients (67 percent).

Predictors of program completion

The multivariate logistic regression analysis included race, age, and back pain as predictors of program completion. When adjusted by the other two variables, each variable was still a significant predictor of completion (p<.02 for all). Expressed in terms of odds ratios, black veterans were 2.5 times more likely to complete the program than white veterans when the analysis did not adjust for any other variable; they were 3.2 times more likely to complete the program than white veterans when the analysis adjusted for age and back pain. When the analysis adjusted for age and race, patients with back pain were about half as likely as those without back pain to complete the program.

Discussion and conclusions

Successful graduation from the residential drug and alcohol program was associated with an absence of back pain. Black veterans were more likely to complete the residential program than white veterans, and older black veterans were more likely to have a successful outcome than younger black veterans.

Completion of the program was not associated with gender, psychiatric diagnosis, past suicide attempts, homelessness, legal history, childhood history of physical or sexual abuse, parental history of addiction, multiple substance dependencies, medical problems other than back pain, or race of the therapist.

The association between back pain and failure to complete treatment may be related to the failure of nonnarcotic interventions, veterans' difficulty tolerating the narcotic-free requirement of the program, or a combination of both these factors.

Several limitations of the study should be mentioned. Because of its retrospective nature, it was not possible to determine if white veterans perceived themselves as being in a minority or if black veterans perceived themselves as being in a majority in the treatment program. Some authors have described race and ethnicity as a cultural concept, not a biological one (21,22,34). It would have been particularly valuable in this study to have information about patients' perceptions of their cultural backgrounds in attempting to determine factors associated with completion rates.

The study did not measure treatment participation or therapists' skills. The analyses did not control for income, benefits claim status, and participation in compensated work programs or other factors that may have had an unmeasured effect on treatment completion rates.

It is also possible that selection bias may have affected outcomes. At intake, the proportions of black and white veterans interviewed reflected the proportions participating in the program; however, some undiscovered bias at admission may have affected the results. Finally, successful completion of substance abuse treatment is believed to be associated with better long-term outcomes, but we were unable to obtain information on outcomes after completion.

Nevertheless, the results of this study are consistent with those of previous reports that have shown that younger individuals are less likely to complete substance abuse treatment and to have poorer outcomes; however, our results contradict those of other studies showing that blacks are less likely to successfully complete treatment programs (4,5,23,24,25).

The fact that whites in this study were less likely to complete treatment and that they were a minority group in terms of numbers of patients in the program supports the idea that minority status within the population of the treatment program may be a stronger predictor of completion than minority status within the geographic area (23). In addition, the results suggest that the potential effect of being in a treatment program's minority racial or ethnic group is not diminished by assignment to a therapist of the same race. Paradoxically, when in the minority, whites may suffer some of the same social pressures that may hinder the successful treatment outcomes of other ethnic and racial minority groups.

Given the complex nature of race and the preliminary nature of this retrospective review, we do not believe that the findings should be used to support segregation of patients by race but rather to raise awareness that minority status may also affect the likelihood of treatment completion in those not typically considered to belong to a minority group.

Dr. Stack is a staff psychiatrist, Dr. Cortina is chief of extended care, and Mr. Samples is a substance abuse counselor at Hampton Veterans Affairs Hospital in Hampton, Virginia. Dr. Stack is assistant professor, Dr. Cortina is associate professor, Dr. Zapata is a psychiatric resident, and Dr. Arcand is education and research coordinator and associate professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk. Send correspondence to Dr. Stack at Geriatrics and Extended Care (18), Hampton VA Hospital, Hampton, Virginia 23667 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 340 veterans in a residential substances abuse treatment program

|

Table 2. Veterans completing a residential substance abuse treatment program, by race, gender, and substance dependence (N=331)

|

Table 3. Veterans with and without the indicated characteristics who completed a residential substance abuse treatment program (N=331)

1. Preliminary Results for the 1997 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Household Survey on Drug Abuse Series H-6. Rockville, Md, Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998Google Scholar

2. Hanson B: Drug treatment effectiveness: the case of racial and ethnic minorities in America: some research questions and proposals. International Journal of the Addictions 20:99-137, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Drake R, Bartels S, Teague G, et al: Treatment of substance abuse in severely mentally ill patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:606-611, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sansone J: Retention patterns in a therapeutic community for the treatment of drug abuse. International Journal of the Addictions 15:711-736, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Greenberg W, Otero J, Villanueva L: Irregular discharges from a dual diagnosis unit. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 20:355-371, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Tolomiczenko GS, et al: Housing placement and subsequent days homeless among formerly homeless adults with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:674-679, 1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Fazzone PA, Holton JK, Reed BG, et al: Substance Abuse Treatment and Domestic Violence. Treatment Improvement Protocol Series 25. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1997Google Scholar

8. Hoff R, Rosenheck R: Utilization of mental health services by women in a male-dominated environment: the VA experience. Psychiatric Services 48:1408-1414, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Ross R, Fortney J, Lancaster B, et al: Age, ethnicity, and comorbidity in a national sample of hospitalized alcohol-dependent women veterans. Psychiatric Services 49:663-675, 1998Link, Google Scholar

10. Substance Use Among Women in the United States. Analytic Series A-3. Rockville, Md, Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse, and Mental Health Services Administration, 1997Google Scholar

11. McLellan A, Luborsky L, O'Brien C: Alcohol and drug abuse treatment in three different populations: is there improvement and is it predictable? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 12:101-120, 1986Google Scholar

12. Holcomb W, Parker J, Leong G: Outcomes of inpatients treated on a VA psychiatric unit and a substance abuse treatment unit. Psychiatric Services 48:699-704, 1997Link, Google Scholar

13. Saxon A, Calsyn D: Effects of psychiatric care for dual diagnosis patients treated in a drug dependency clinic. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 21:303-313, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Galanter M, Egelko S, Edwards H, et al: Can cocaine addicts with severe mental illness be treated along with singly diagnosed addicts? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 22:497-507, 1996Google Scholar

15. Wenzel S, Bakhtiar L, Caskey N, et al: Dually diagnosed homeless veterans in residential treatment: service needs and service use. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 184:441-444, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rosenheck R, Seibyl C: Effectiveness of treatment elements in a residential work therapy program for veterans with severe substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 48:928-935, 1997Link, Google Scholar

17. Weiss E, Longhurst J, Mazure CM, et al: Childhood sexual abuse as a risk factor for depression in women: psychosocial and neurobiological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:816-828, 1999Link, Google Scholar

18. Dinwiddle S, Reich T: Genetic and family studies in psychiatric illness and alcohol and drug dependence. Journal of Addictive Disease 12:17-27, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Prescott C, Kendler K: Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol abuse and dependence in a population-based sample of male twins. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:334-340, 1999Link, Google Scholar

20. Schnoll S, Finch J: Medical education for pain and addiction: making progress toward answering a need. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics 22:252-256, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. LaVeista T: Beyond dummy variables and sample selection: what health services researchers ought to know about race as a variable. Health Services Research 29:1-16, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

22. Cooper R, David R: The biological concept of race and its application to public health and epidemiology. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 2:97-116, 1986Google Scholar

23. McCaughrin W, Price R: Effective outpatient drug treatment organizations: program features and selection effects. International Journal of the Addictions 27:1335-1358, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Haywood T, Kravitz H, Grossman L, et al: Predicting the "revolving door" phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856-861, 1995Link, Google Scholar

25. Dale R, Dale F: The use of methadone in a representative group of heroin addicts. International Journal of the Addictions 8:293-308, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Howard D, LaVeista T, McCaughrin W: The effect of social environment on treatment outcomes in outpatient substance misuse treatment organizations: does race really matter? Substance Use and Misuse 31:617-638, 1996Google Scholar

27. Rosenheck R, Leda C, Frisman L, et al: Homeless mentally ill veterans: race, service use, and treatment outcomes. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:632-638, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Leda C, Rosenheck R: Race in the treatment of homeless mentally ill veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:529-537, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Rosenheck R, Seibyl C: Participation and outcome in a residential treatment and work therapy program for addictive disorders: the effects of race. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1029-1034, 1998Link, Google Scholar

30. Brown B, Joe G, Thompson P: Minority group status and treatment retention. International Journal of the Addictions 20:319-335, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Sue S: Psychotherapeutic services for ethnic minorities: two decades of research findings. American Psychologist 43:301-308, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Rosenheck R, Fontana A, Cottrol C: Effect of clinical-veteran racial pairing in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:555-563, 1995Link, Google Scholar

33. Blank M, Tetrick F, Brinkley DF, et al: Racial matching and service utilization among seriously mentally ill consumers in the rural south. Community Mental Health Journal 30:271-281, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Williams D, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Warren R: The concept of race and health status in America. Public Health Reports 109:26-41, 1994Medline, Google Scholar