Focus on Women : Age, Ethnicity, and Comorbidity in a National Sample of Hospitalized Alcohol-Dependent Women Veterans

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Treatment patterns in a national sample of hospitalized women veterans diagnosed with alcohol dependence were identified with the goal of improving health services to women veterans with alcohol-related disorders. METHODS: Information from VA's patient treatment file for fiscal year 1993 was used to identify 854 women veterans diagnosed with alcohol dependence. Of that group, 546 received a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence, and 308 received a secondary diagnosis of alcohol dependence after they sought treatment for other health problems. Chi square tests and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to examine relationships between the sociodemographic profiles of these women and the types of services they received. RESULTS: The study population's largest age group (49 percent) was 30 to 39 years old. Fifty-two percent of the women were divorced or separated, and 62 percent were Caucasian. The overwhelming majority of comorbid diagnoses were of psychiatric disorders. Overall, only 47 percent of the 854 patients received formal treatment for their alcohol disorder, and only 34 percent completed alcohol treatment. Women over age 60 were significantly less likely than women in other age groups to enter or complete formal treatment. Native-American women were significantly more likely than Caucasians or African Americans to receive formal alcohol treatment services. CONCLUSIONS: The results indicate a need for targeting interventions more effectively in certain groups of women veterans diagnosed with alcoholism. Low completion rates also suggest a need for greater incentives for patients to complete treatment programs.

Billions of dollars a year are spent directly and indirectly on alcohol-related disorders, making them a leading public health problem among women and men in the United States (1). Past studies on alcoholism were limited to all-male populations, analyzed male and female patients together, or contained too few women to reach significant conclusions (2,3). Due largely to the increasing number of alcohol-dependent women (4,5), a clinical focus on women and alcohol consumption has emerged (6,7).

Basic biological and psychological differences exist between women and men in the effects of alcohol. Identical doses of ethanol per kilogram of body weight result in significantly higher blood-alcohol levels in women than in men (8). Alcohol-related diseases such as fatty liver, hypertension, obesity, anemia, malnutrition, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage occur among women with shorter drinking histories and lower levels of consumption than men (9,10,11). Women with alcohol disorders are more likely to be divorced (12), more likely to relate the onset of excessive drinking to a stressful life event (3), and more likely to present with comorbid drug abuse, particularly use of amphetamines, tranquilizers, and sedatives (13,14).

The symptoms that commonly prompt clinicians and counselors to refer male patients to treatment programs may be less appropriate indicators for women. For example, women more often relate the symptoms associated with excessive drinking to anxiety or depression than do men (15). Also, women face different barriers to treatment such as unavailability of child care, financial limitations, and lack of services tailored to their specific needs (16,17). As a result, despite the increasing incidence of alcohol disorders among women, male-to-female ratios in alcohol treatment facilities remain fairly constant, at four to one (18).

A recent study of female veterans revealed that they were less likely to receive substance abuse treatment than male veterans (19). However, the study did not examine specific differences within subpopulations of women veterans that might explain why women in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system are less likely to use substance abuse treatment services and remain in treatment. The number of women veterans is increasing, even as the total number of veterans decreases (20). However, women veterans are significantly less likely to utilize VA health care benefits than their male counterparts, and they selectively use health care services for protracted or chronic care (21).

In 1985 alcohol abuse and dependence treatment for both men and women cost VA $188 million (1). However, most sociodemographic information about the hospitalized alcohol-dependent veteran is about men (1,22). The national study of hospitalized women veterans reported here provides an opportunity to examine health care issues for alcohol-dependent women in a public setting. Our study examined data from a relatively large group of alcohol-dependent women, and thus our results can provide insight into the treatment needs of other women with alcohol disorders. Underdiagnosis of alcohol problems is common (23), and it is likely that the sample in this study is an underestimation of women veterans with alcohol disorders.

In this observational study of women diagnosed with alcohol dependence, we expected age and ethnicity to be associated with the type of alcohol services received. We hypothesized that older women would be less likely to be treated for alcohol disorders and that Native American women would be more likely to be treated for alcohol disorders. We also expected that psychiatric diagnoses, rather than medical diagnoses, would be the predominant comorbid diagnoses among alcohol-dependent women, which would be consistent with other studies (3,15).

Methods

Sample

Data about hospitalizations of women veterans with alcohol-related disorders were extracted from the national VA patient treatment file. The database does not include any personal identifiers of the subjects involved. In accordance with institutional guidelines for human subjects review, no identifying information of subjects was known at any point to the researchers.

The database stores administrative, demographic, and clinical information about each episode of inpatient care provided at the 172 VA medical centers across the country. Data relating to the bed section (hospital ward) occupied by the patient during the admission, along with specific bed section diagnoses, are included in the database. Bed sections are grouped by the medical service responsible for the patient's care. These groups include surgery, medicine, and psychiatry (acute and long term), as well as alcohol and drug treatment. The database also includes information from each bed section if the patient is transferred from one bed section to another during the admission.

Of the 172 VA medical centers nationwide, 127 had formal inpatient alcohol dependence treatment programs in 1993. These programs had widely varying lengths of stay, averaging 25.2 days and ranging from 12 days to 56 days. However, most of the programs required inpatient stays of either three weeks (25 percent) or four weeks (36 percent) to complete. Although 110 (87 percent) of these programs were located in the substance abuse bed sections of the respective medical center, some were housed in alcohol treatment, drug treatment, or acute psychiatry bed sections.

For an episode of inpatient care to be included in the study, the patient must have been identified as female, discharged from a VA medical center during fiscal year 1993 (October 1, 1992, to September 30, 1993), and assigned a primary or secondary diagnosis of alcohol dependence not in remission (ICD-9-CM and DSM-III-R codes 303.9, 303.90, 303.91, or 303.92) (24,25). Episodes of care were categorized into four mutually exclusive comparison groups: completed formal inpatient alcohol treatment, did not complete formal inpatient alcohol treatment, entered alcohol detoxification apart from formal treatment, and did not receive direct services for alcohol-related disorders. Information used to categorize each episode included the primary diagnosis, length of stay, and inpatient unit on which the episode occurred.

For an episode to be included in the category of completed formal alcohol treatment, women with a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence must have completed at least 90 percent of the alcohol dependence treatment program's modal length of stay for that VA medical center. Determinations of modal stays for individual centers were required because lengths of stay varied between programs.

Inclusion in the category of did not complete formal alcohol treatment required women with a primary alcohol dependence diagnosis to complete more than five days but less than 90 percent of the modal length of stay for that program. Requiring a six-day minimum stay excluded women admitted for detoxification only.

Women in the alcohol detoxification group had a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence and a stay of five days or less in an alcohol dependence treatment program or any length of stay in a unit that was not part of the program. For women with a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence who did not enter formal inpatient treatment, it was assumed that detoxification was the only direct alcohol service rendered. This assumption is based on the milieu-dependent nature of formal alcohol treatment (26).

Women who received no alcohol treatment included those who had a non-alcohol-related primary diagnosis and a secondary diagnosis of alcohol dependence not in remission and who were placed in any bed section other than the one classified for formal alcohol treatment at that VA medical center.

To ensure independence among observations in the study, only one episode for each patient was included. If a patient was hospitalized multiple times during the year, the episode chosen was the one during which the most intensive level of alcohol treatment was provided. If a patient had multiple episodes of treatment at the same level of intensity, one episode was randomly selected. Patients who had no formal alcohol treatment but who received drug treatment during their hospital stay were excluded from the study.

Data analysis

We identified statistical associations using chi square tests of independence between the treatment groups and demographic variables. We used multivariate logistic regression analyses (27) to model each group's probability of entering alcohol treatment as a function of the explanatory variables of age, race-ethnicity, marital status, and comorbidity. Because of the relatively large sample size, we had statistical power to detect small differences between groups. Therefore, the clinical relevance of these small significant differences should be interpreted with caution.

Age was defined as an ordinal variable with five age groups: under age 30, from 30 to 39 years, from 40 to 49 years, from 50 to 59 years, and age 60 or older. Marital status was collapsed into a dichotomous variable of married or not married. Race-ethnicity was specified as Hispanic, Caucasian, Native American, or African American. Psychiatric and medical comorbidity was defined as the number of mental or physical diagnoses per subject. Explanatory variables were specified such that the reference group in logistic regression analyses was defined as women who were under age 30, Caucasian, and married, with no comorbid psychiatric or medical diagnoses.

Three increasingly specific logistic regression equations were estimated. The first modeled the probability, as a function of the explanatory variables, of receiving some direct inpatient service primarily for alcohol dependence—either detoxification only, incomplete treatment, or complete treatment—compared with receiving no direct services. The second modeled the probability of entering formal treatment—complete or incomplete—compared with detoxification only for women receiving some direct alcohol services. The final equation modeled the probability that women who entered treatment would complete the treatment program.

Results

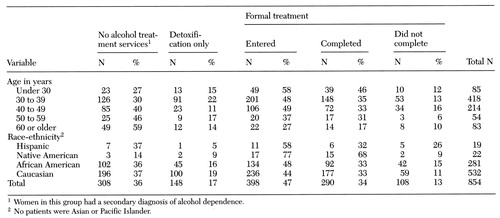

As Table 1 shows, the sample included 854 women veterans. The age distribution in this sample is similar to that of the overall female veteran population (28). Forty-nine percent were between the ages of 30 and 39. In addition, 62 percent of the women were Caucasian, 52 percent were either divorced or separated, and 26 percent had never been married.

Of the 854 alcohol-dependent women, 546 (64 percent), received care specifically for their alcohol disorder. A total of 290 (34 percent) completed treatment, 108 (13 percent) entered but did not complete treatment, and 148 (17 percent) underwent detoxification but did not enter treatment. The remaining 308 women (36 percent) received no direct inpatient services for their alcohol disorders in fiscal year 1993.

Comorbidity

The 546 alcohol-dependent women who received any form of direct VA service for alcohol disorders (formal inpatient treatment or detoxification only) in fiscal year 1993 received a total of 1,934 secondary diagnoses. The most frequent secondary diagnoses were drug-related disorders (382 patients, or 20 percent) and other non-drug-related psychiatric disorders (the same number of patients, 382 patients, or 20 percent), followed by digestive disorders (153 patients, or 8 percent) and genitourinary disorders (120 patients, or 6 percent).

In contrast, liver disease and cardiac disease, two comorbid medical conditions usually associated with alcohol-related disorders, individually accounted for less than 1 percent of the secondary diagnoses. However, the secondary diagnosis of a digestive disorder, such as esophageal varices and intestinal ulcers, was made for 141 of the 546 women who received direct alcohol services (26 percent).

Among the 308 alcohol-dependent women who received no direct alcohol services—neither treatment nor detoxification—psychiatric disorders were again the predominant primary diagnoses. Overall, 185 of the women receiving no direct alcohol services (60 percent) had a primary psychiatric diagnosis, including psychosis in 27 cases (9 percent), depression in 46 cases (15 percent), bipolar disorder in 25 cases (8 percent), and other psychiatric diagnoses. Liver disease including cirrhosis was the primary medical diagnosis for 12 of the women in this group (4 percent), followed by pancreatic disease in five cases (2 percent).

Age

A significant relationship between age and treatment group was found (χ2=46.8, df=12, p<.001). Overall, women age 60 and older were the least likely to receive any direct alcohol hospitalization and the most likely to be hospitalized for other primary diagnoses. By contrast, women under age 30 were most likely to complete formal inpatient treatment and least likely to be hospitalized for other diagnoses.

Of the 83 women over age 60, a total of 61 (73 percent) did not enter formal inpatient treatment for their diagnosis of alcohol dependence. Of the 54 women between the ages of 50 and 59, 34 (63 percent) did not enter formal inpatient treatment. By contrast, of the 85 women under age 30, only 36 (42 percent) did not enter formal treatment. In addition, of those who entered formal treatment, women age 60 and older were less likely to complete treatment, and women under age 30 were more likely to complete treatment.

Race-ethnicity

Bivariate analysis revealed a significant association between race-ethnicity and whether patients received or completed formal inpatient alcohol treatment (χ2=19.6, df=9, p<.02). However, it should be noted that the sample sizes for Native-American and Hispanic women were small_22 and 19 women, respectively—limiting the precision of data analysis. However, these samples represented the total number of alcohol-dependent Native-American and Hispanic women veterans receiving services for alcohol disorders during fiscal 1993. Therefore, the significant differences between ethnicity and alcohol treatment are reported but should be interpreted with caution.

Of the 22 Native-American women, 17 entered formal treatment (77 percent; 95 percent confidence interval=59 percent to 95 percent), and 15 completed treatment (68 percent; CI=49 percent to 88 percent). By contrast, less than half of the Caucasian and African-American women entered treatment, and a substantial number did not complete it. Compared with Caucasians and African Americans, Hispanic women had a somewhat higher rate of entering treatment but a similar completion rate. Of the 281 African-American women, 134 (48 percent) entered treatment, and 92 (33 percent) completed it. Of the 532 Caucasian women, 236 (44 percent) entered treatment, and 177 (33 percent) completed it. Of the 19 Hispanic women, 11 entered treatment (58 percent; CI=43 percent to 73 percent), and six completed it (32 percent; CI=4 percent to 60 percent).

Multivariate analysis

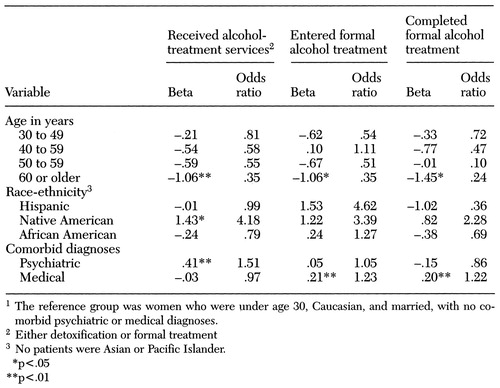

Table 2 shows the results of the logistic regression analyses. Controlling for race-ethnicity and comorbid diagnoses, we found that compared with women under 30, women age 60 and older were significantly less likely to receive any direct alcohol services (p=.003), were significantly less likely to enter formal treatment if they received any direct alcohol services (p=.04), and were significantly less likely to complete treatment after treatment entry (p=.02)

When the analysis controlled for age and comorbidity, Native-American women were four times more likely to receive direct alcohol services (formal treatment or detoxification) than Caucasian women (p=.03). However, no other race-ethnicity variables predicted receiving direct treatment services, entering treatment, or completing treatment.

When the analysis controlled for demographic factors, the number of mental health diagnoses was a significant predictor of receipt of direct alcohol services (p<.001), and the number of medical diagnoses was a significant predictor of entering formal treatment (p<.001) and of completing formal treatment (odds ratio=1.2, p=.006). The comparison category in this analysis was entering detoxification.

Discussion and conclusions

One of the strengths of this study is its relatively large and diverse sample, which allowed greater confidence in the results than in previous studies of alcoholic women. Our data point out a potential need in the VA health care system to enhance the processes for placing certain women diagnosed with alcohol disorders into formal treatment programs and to retain them for the duration of the programs.

The results show that less than half (47 percent) of the alcohol-dependent women identified in this national study received treatment for their disorder. In fact, the number of women receiving no direct services was greater than the number of women who completed formal treatment. Women age 60 and older were significantly less likely to enter or complete formal treatment than those in other age groups. It is possible that these older women with alcohol disorders had previously participated in alcohol treatment programs, making it less likely that they would be referred for or request formal treatment.

It is also impossible to know which of the women in the no-treatment group received treatment outside the VA system. However, in general, veterans with alcohol-related disorders, as well as elderly veterans, are of lower socioeconomic status than the general public and would be less likely to be able to afford outside services (29,30). Furthermore, it is impossible to know which of the untreated women were offered treatment but refused it.

Because of the tremendous medical and psychiatric comorbidity associated with alcoholism, as well as the relapsing and remitting course of this disease, previous treatment failure or reluctance to enter treatment requires further study so that effective strategies can be identified for including these older women in treatment. The results of this study are relevant for clinical and treatment policy. Procedures for detecting and treating alcohol-related disorders might need to be modified to retain more elderly women in treatment. More aggressive treatment of comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions in an alcohol dependence treatment program might help place more older alcohol-dependent women in treatment and ensure treatment completion. A program's ability to treat chronic medical illnesses is important in providing care to elderly patients with alcohol disorders.

Native-American women veterans were more likely to receive and to complete treatment than all other ethnic groups. Perhaps because of the greater recognition of alcohol problems among Native Americans, they are more likely to be referred for, and encouraged to complete, treatment. It is possible that the increase in placement and retention in VA alcohol dependence treatment programs of Native-American women is due to clinicians' increased awareness of alcohol disorders among Native Americans, as well as an increased accommodation of issues specific to them in the treatment milieu. If so, there is reason to believe that interventions to increase clinical awareness of other at-risk populations, such as elderly alcohol-dependent women, could result in equally appropriate placement and retention in a treatment program.

Comorbid psychiatric disorders were relatively common in this group of hospitalized women, constituting 60 percent of the primary diagnoses for those receiving no direct alcohol services and 20 percent of secondary diagnoses for those receiving some form of direct inpatient alcohol services. We do not know what leads to the clinical decision to place women in formal alcohol treatment rather than in psychiatric bed sections, although in this study these decisions may have been a function of the most pressing problem at the time of admission or of bed availability.

Data in the VA patient treatment file also do not tell us which of these women might have participated in special programs for patients with dual diagnoses. However, it is likely that few received specialty care for both disorders because traditionally substance abuse treatment programs and psychiatric treatment programs are separate in the VA system. Educational and treatment interventions need to be designed within the VA system for this group of women, especially interventions for women with alcohol problems who are placed in psychiatric bed sections. These data point to the growing clinical complexity of treating women with alcohol disorders and the importance of multidimensional treatment plans.

Increased clinical awareness about gender differences in alcohol disorders is needed. Alcohol-dependent women are more likely than their male counterparts to present with psychiatric complaints or prominent psychiatric symptoms (15). Because the treatment of psychiatric disorders and alcohol disorders is often conducted in different hospital sections and outpatient units, placement in a psychiatric bed section could preclude aggressive treatment of alcohol disorders. The separate treatment of psychiatric and alcohol disorders may be less useful, even harmful, to the female alcoholic.

The classical understanding of denial as being a lack of insight into current or past problems caused by alcohol might need to be redefined for women. Women are more likely to admit psychiatric disturbance, and such emotional openness could be misinterpreted by the clinician as being an indication of insight. In fact, women may be no more likely than men to relate their problems to alcohol.

Additional research is needed to better understand the diagnostic and treatment needs of this special population. Further work should identify barriers to treatment within the VA system. If our results are indicative of the wider picture, then new ideas are needed for improving placement of certain alcohol-dependent women in effective treatment programs. Treatment as it now exists very likely costs more money in the long run because of the necessity of treating related comorbid mental and medical health problems.

Dr. Ross, Dr. Fortney, and Dr. Booth are affiliated with the Centers for Mental Healthcare Research of the department of psychiatry at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Dr. Ross is also with Greater Assistance to Those in Need, Inc., 4813 West Markham Street, Hendrix Hall, Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Lancaster is affiliated with the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Field Program in North Little Rock, Arkansas, as are Dr. Fortney and Dr. Booth. This paper is one of several in this issue focused on women and chronic mental illness.

|

Table 1. Age and race-ethnicity of 854 women veterans diagnosed with alcohol dependence, by type of alcohol treatment services received and whether they completed treatment

|

Table 2. Logistic regression model of variables predicting receipt and completion of formal alcohol treatment among 854 woman veterans diagnosed with alcohol dependence1

1. Rice DP, Kelman S, Miller LS, et al: The Economic Costs of Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Illness:1985. Report submitted to the Office of Financing and Coverage Policy of the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. San Francisco, University of California, Institute for Health and Aging, 1990Google Scholar

2. Russell M, Henderson C, Blume SR: Children of Alcoholics: A Review of the Literature. New York, Children of Alcoholics Foundation, 1985Google Scholar

3. Blume SB: Women and alcohol: a review. JAMA 256:1467-1470, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Weisner C, Schmidt L: Gender disparities in treatment for alcohol problems. JAMA 268:1872-1876, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wilsnack SC, Wilsnack RW, Klassen AD: Epidemiological research on women's drinking, 1978-1984, in Women and Alcohol: Health-Related Issues. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1986Google Scholar

6. Alcohol and Women. Pub (ADM) 80-835. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1980Google Scholar

7. Woman and Alcohol: Health-Related Issues. Pub (ADM) 86-1139. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1986Google Scholar

8. Jones BM, Jones MK: Women and alcohol: intoxication, metabolism, and the menstrual cycle, in Alcoholism Problems in Women and Children. Edited by Greenblatt M, Schuckit MA. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1976Google Scholar

9. Ashley MJ, Olin JS, le Riche WH: Morbidity in alcoholics: evidence for accelerated development of physical disease in women. Archives of Internal Medicine 137:883-887, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gavaler JS: Sex-related differences in ethanol-induced liver disease: artifactual or real? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 6:186-196, 1982Google Scholar

11. Schuckit MA, Anthenelli RM, Bucholz KK, et al: The time course of development of alcohol-related problems in men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 56:218-225, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Beckman LJ: Women alcoholics: a review of social and psychological studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 36:797-824, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Brady KT, Grice DE, Dustan L, et al: Gender differences in substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1707-1711, 1993Link, Google Scholar

14. Gomberg ES: Women and alcoholism: psychosocial issues, in Women and Alcohol: Health-Related Issues. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1986Google Scholar

15. Thom B: Sex differences in help-seeking for alcohol problems:1. the barriers to help-seeking. British Journal of Addiction 81:777-788, 1986Google Scholar

16. Beckman LJ, Amaro H: Personal and social difficulties faced by women and men entering alcoholism treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 47:135-146,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Roman PM: Women and Alcohol Use: A Review of the Research Literature. Pub (ADM) 88-1574. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1988Google Scholar

18. Highlights From the 1987 National Drug and Alcoholism Unit Survey (NDATUS). Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1989Google Scholar

19. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: Utilization of mental health services by women in a male-dominated environment: the VA experience. Psychiatric Services 48:1408-1414, 1997Link, Google Scholar

20. Sorensen KA, Feild TC: Statistical Brief: Projections of the US Veteran Population:1990 to 2010. Washington, DC, National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics and Assistant Secretary for Policy and Planning, 1994Google Scholar

21. Dvoredsky AE, Cooley W: The health care needs of women veterans. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:1098-1102, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

22. Booth BM, Blow FC, Cook CAL, et al: Age and ethnicity among hospitalized alcoholics: a nationwide study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 16:1029-1034, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Moore RD, Bone LR, Geller G, et al: Prevalence, detection, and treatment of alcoholism in hospitalized patients. JAMA 261:403-407, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Clinical Modification of the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases, 9th rev. Geneva, World Health Organization, Commission on Professional and Hospital Activities, 1978Google Scholar

25. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

26. Weiss RD: Inpatient treatment, in Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. Edited by Galanter M, Kleber HD. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

27. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression. New York, Wiley, 1989Google Scholar

28. Schwartz SH, Klein RE: Characteristics of the Veteran Population by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: Data From the 1990 Census. Washington, DC, National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics, 1994Google Scholar

29. Schuckit MA, Schwei MG, Gold E: Prediction of outcome in inpatient alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 47:151-155, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O'Brien C, et al: Is treatment for substance abuse effective? JAMA 247:1423-1428, 1982Google Scholar