Planning by Older Mothers for the Future Care of Offspring With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined permanency planning by older mothers for their adult offspring with long-term mental illness, including extent of residential and financial planning, desire for future family care, and perceived need for and use of services to assist with planning. METHODS: Mail surveys were completed by 157 mothers (mean age, 67 years) from 41 states who lived with and provided care to adult offspring with serious mental disorders (mean age, 38 years). The offspring were mostly males (76 percent) and had diagnoses primarily of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (60 percent), multiple diagnoses (20 percent), or bipolar disorder (16 percent). RESULTS: Only 11 percent of mothers reported definite plans for their offspring's future residence, and many had done little or no planning. Three-quarters of respondents hoped that another family member would assume care, yet only one-quarter thought such arrangements would definitely occur. Two-thirds of the respondents had completed financial plans. Although more than two-thirds expressed the need for services to help with planning, less than one-third had used such services. More than half reported awareness of age-related changes in themselves or their spouse as the primary reason for planning. CONCLUSIONS: Older parents of adults with long-term mental illness need professional help with planning for their offspring's future. This assistance should focus on mechanisms such as estate planning to enable case management and other services after parents' death. The involvement of nondisabled siblings in planning should also be encouraged.

Despite growing interest in the problems of aging caregivers of relatives with lifelong disabilities, scant attention has been paid to older parents who care for offspring with serious mental illness. Although the need for policy makers and service providers to address the problems facing these aging parents has been widely asserted (1,2,3,4,5,6,7), few empirical data are available on their caregiving circumstances. The extent to which older parents have planned for the future well-being of their disabled offspring is a crucial issue that has been virtually ignored.

Parents' ability to provide the support and care needed by an offspring with mental illness may be compromised as the parents grow older (1,2,3,4,5,6,7). Age-related changes such as decreased energy, increased sensory loss, and physical disability as well as greater vulnerability to illness foreshadow the end of the caregiving role (8). Moreover, the stresses associated with family caregiving can exacerbate these age-related changes. Greenberg and colleagues (9), for example, found that subjective burdens such as the stigma of mental illness and worry about the disabled offspring's future were the strongest predictors of self-reported health in their sample of older mothers.

Other investigators have similarly observed tremendous apprehension in family caregivers about what will happen to their relative with serious mental illness when they become frail or die (3,4,5,6). A recent survey of family members of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) revealed that "what will happen to my relative when I am gone" was the greatest source of psychological pain for 74 percent of respondents (5). A dominant concern expressed by older parents in a study by Cook (6) was whether disabled offspring would learn to be independent before they "had no choice."

Making plans for the future is especially crucial when offspring are living with their aging parents. In a national sample of NAMI families, Skinner and colleagues (10) found that 42 percent of relatives with serious mental illness lived at home, and only 14 percent lived in supervised housing. Lefley (11) reported that 85 percent or more of family caregivers are parents, and many are elderly. Substantial numbers of families are thus faced with the issue of where their relative with mental illness will live when parents can no longer provide care. If plans are not made, the mental health system may become overwhelmed by the demand for services as the baby boom generation begins to lose caregiving parents.

Whether parents develop plans for the future also has important consequences for offspring with mental illness. Many tend to develop trust in others slowly, adjust to change with difficulty, and resist the community services that are available to them (12). Lack of planning to ensure continuity of care may thus result in considerable trauma for these offspring when their parents die or become too frail to maintain the caregiver role.

Despite the profound need for planning expressed by caregiving parents of adults with serious mental illness, there is no published research on the extent of planning within this population. However, investigators have observed low rates of planning among older parents of adults with mental retardation (13,14). Because both types of "perpetual parents" face similar barriers to planning, it is sensible to hypothesize that older parents of adults with mental illness will likewise report low rates of planning. Barriers to planning encountered by both groups include difficulty in giving up long-term caregiving routines, interdependency with offspring, unattractive or unavailable residential options, lack of information about and assistance with planning, fears that offspring will not adjust to change, and parents' inability to accept their own mortality (15).

The purpose of the study reported here was to examine permanency planning in a national sample of older mothers who live with and provide care to an adult son or daughter with a serious mental illness. Specific behaviors examined included the extent of residential and financial planning achieved by the respondents, the desire for other family members to assume future caregiving responsibilities, and the perceived need for and use of the formal service system to assist with planning.

Methods

Participants

Mothers aged 50 and older who resided with a mentally ill son or daughter were recruited between 1995 and 1997 through announcements in local, state, and national NAMI newsletters to participate in a national survey on planning for the future. Participation was limited to mothers because they perform the bulk of caregiving for adults with mental illness (6,11).

This recruitment yielded 196 respondents from 41 states, 157 of whom met the criteria of living with their offspring and thus served as the study sample. The respondents in the study sample ranged in age from 50 to 88 years (mean±SD age=67±7.68 years). The majority were non-Hispanic white (144, or 92 percent), were married (96, or 61 percent), had at least a high school education (153, or 98 percent), and reported their health as good or excellent (123, or 79 percent).

Their offspring were primarily male (120, or 76 percent), aged 20 to 58 years (mean±SD age=38±8.09 years). The majority had diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (94, or 60 percent); the rest had multiple disorders (31, or 20 percent), bipolar disorder (25, or 16 percent), or other forms of psychiatric illness (seven, or 5 percent) such as major depression. The majority of offspring (114, or 73 percent) were reported by their mothers to be in good or excellent physical health. Only one-third (N=53) were involved in activities outside of the home—for example, day programs, supported work, or competitive jobs—and half spent their typical day at home. Most mothers indicated that their offspring relied on them either for help with everyday chores such as cooking, cleaning, and laundry (74, or 47 percent) or for such chores plus daily structure (64, or 41 percent). The communities where the families resided were fairly evenly divided among large cities (41, or 26 percent), small cities (37, or 24 percent), and rural areas (26, or 17 percent).

The profile of this sample is remarkably similar to that of prior NAMI studies (11), which found the modal pattern in caregiving families to consist of an aging parental caregiver, typically a mother in her late fifties to her seventies, who is taking care of a mentally ill son approaching middle age.

Procedure

Mothers were mailed a self-administered questionnaire requesting information on family background, use of formal and informal supports, circumstances surrounding family caregiving, and indexes of maternal well-being. An initial version of the questionnaire, derived from the senior author's research on older mothers of adults with mental retardation, was adapted for this study through pilot testing with mothers of mentally ill adults. All questions reported here involved the fixed-choice response alternatives described below. Surveys were to be completed without assistance and returned in a pre-addressed, stamped envelope. The return rate exceeded 90 percent.

Results

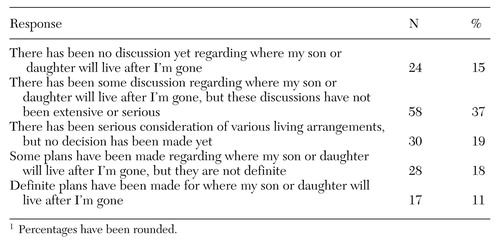

Two questions concerned the degree to which mothers had engaged in planning for their offspring's future residence: "At what stage are you in planning for your child's future living arrangements?" and "How much time and effort have you spent in planning for where your son or daughter will live after you are gone?" The data in Table 1 indicate that although 133 respondents, or 85 percent, had engaged in residential planning to at least some degree, only 17 mothers, or 11 percent, had made plans that they regarded as definite. Nearly half of the mothers (N=73) had devoted either "no effort at all" or "very little effort" toward such planning, whereas about one-fourth (N=35) had devoted either "considerable effort" or "great effort" (data not shown). The remainder had put "moderate effort" into planning (N=47, or 30 percent).

The 133 mothers who had engaged in some degree of residential planning were then asked, "What is the main reason that you have begun to plan for your offspring's future residence?" More than half (73, or 55 percent) reported awareness of aging and mortality in themselves or their spouse as the chief reason. Ensuring their offspring's independence (23, or 17 percent) and future adjustment (21, or 16 percent) were the next most common reasons. The Spearman rank-order correlation between mother's age and stage of planning was small and nonsignificant, however, suggesting that a substantial number of even the oldest mothers had not engaged in resolute planning.

The mothers who had begun planning were also asked whether they had ever discussed this matter with their disabled offspring. A total of 105, or 79 percent, reported that such discussions had occurred, although only 53, or 40 percent, of this group said that their offspring had agreed with them during these discussions.

In contrast to the low rate of serious residential planning reported by the mothers in our sample, the extent of financial planning was much higher. A majority (103, or 66 percent) reported that financial arrangements had been made for their child's future. Trusts (34 percent) and money willed to another relative in the offspring's behalf (21 percent) were the predominant arrangements.

We also asked our respondents whether there were family members whom they would like to see assume the primary responsibility, either in or outside their home, for their offspring with mental illness. More than three-fourths (119, or 76 percent) indicated that they would like a sibling of the disabled offspring to assume this role, with 62 respondents (40 percent) citing a sister and 52 (33 percent) a brother as the desired future caregiver. Yet when asked, "How certain are you that this family member will actually assume primary caregiving responsibility for your son or daughter?" only 29 (25 percent) of the mothers who wished that a sibling would assume care felt that it would definitely happen. However, 43 (37 percent) believed that these arrangements would "probably occur."

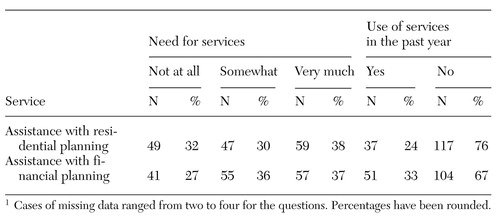

We also asked questions about the need for and use of formal services to assist with permanency planning. The results of these queries are summarized in Table 2. More than two-thirds of respondents perceived a need for services related to both residential and financial planning. However, the reported use of such services was low.

Discussion

As expected, the low rate of residential planning reported by our sample of older mothers of mentally ill adults is similar to that found in prior studies of parents caring for adults with mental retardation (13,14). As noted, this similarity may be due to the barriers both groups of perpetual parents face—attachment to routines, interdependency with offspring, dissatisfaction with residential options, lack of information about and assistance in planning, fears about their offspring's ability to adjust, and unwillingness to face their own mortality (15).

Hatfield (16) surveyed aging parents of adults with mental illness and found that many in her sample reported such barriers to residential planning as the unavailability of housing (68 percent) and the poor quality of existing housing (42 percent). More than 70 percent said their relative was fearful of leaving home or too comfortable at home to consider living elsewhere, and worry about their offspring was identified as the main barrier to letting go. Parents expressed great concern over such issues as safety, cost, and staff competence. It is not surprising, then, that only about one-tenth of our sample had made definite residential plans for their disabled offspring.

There may be other reasons, too, that so few in our sample had established definite residential plans. If their offspring's diagnosis was quite recent, parents may have needed to work through their initial disbelief, loss, or anger before engaging in planning. Our findings also suggest that offspring with mental illness may oppose plans proposed by parents. Persons with mental illness may be anxious about relinquishing the security of the parental home for an unknown situation requiring many adjustments, and cognitive impairments can make it difficult for them to envision a future without parents (17).

A potential complicating factor is that the course of mental illness often encompasses emotional and behavioral irregularities, leaving many parents unable to predict what services their son or daughter may need in the future (3). Parents may harbor hope that their offspring will get well enough over time to become independent. They also face a double bind when they are encouraged by professionals to foster independence and growth in their offspring (6). If parents refuse to let go, they are seen as "bad." But if they do allow separation to occur and the child fails, they may face anger and disappointment, internally as well as from their offspring. Hence parents may attempt to preserve their offspring's self-esteem by avoiding situations that might result in failure.

Individuals suffering from a serious mental illness need constructive ways to spend their days. However, half of the mothers in our sample said their offspring had no structured daily activities. Smith and colleagues (18) found that the extent of residential planning by older mothers of adults with mental retardation was related to use of day program services. They concluded that service use facilitates planning by diminishing parents' apprehensiveness about the service system that may ultimately be responsible for the care of their offspring.

Another significant finding of our study was the disparity between parents' preference for siblings to serve as future caregivers and parents' expectations that they will actually do so. Earlier research by Pruchno and colleagues (19) likewise found a strong desire among older mothers to have their offspring's siblings assume responsibility. In reality, however, parents seem to realize that many siblings may be unable to assume direct care of a brother or sister with mental illness because of the demands of their own lives. Discussions between parents and their nondisabled children must occur to clarify what roles siblings will play. In any case, the future involvement of siblings in caregiving is likely to be influenced by their experiences growing up in a family with a member who has a serious mental illness (20).

Our study also revealed that many older mothers were not using services to help them in planning, although these same parents expressed considerable need for such assistance. Mental health service systems may be slow in recognizing the special problems that arise as caregivers age and their offspring's need for community services becomes imperative. Smith and Tobin (21) discovered ageism in the developmental disabilities service system that may exist among mental health professionals in general. The case managers in their study viewed older parents' avoidance of planning for the future as an act of selfishness, and they acknowledged considerable conflict and mistrust between them and older parents. The authors concluded that tension between older parents and professionals could be alleviated through increased training in gerontology.

Conclusions

Older mothers in this study were further along in their financial planning than they were in residential planning, implying that many parents were thinking of the future. However, residential planning seemed to be an especially difficult problem for them to resolve. In order to make residential plans, parents may have to interact with a disabled offspring who is opposed to leaving the parental home, as suggested by our finding that only 40 percent of the mothers reported agreement with their offspring in discussions of this issue. The mothers in our study also appeared to be facing a discrepancy between their desire for other family members to provide care for their disabled offspring and the likelihood that this would actually occur. Also, many parents indicated a need for professional assistance with planning that was not being met at the time of the study.

Practitioners thus should be proactive in identifying clients with aging parents and in devising ways to prepare the entire family for the inevitable separation. Consumers may need considerable help in facing the reality of parental loss and in coping with anxiety over what will happen to them. Ideally, families and practitioners should work together to achieve the necessary separation with minimal trauma to the parent and their offspring with serious mental illness.

This descriptive study is a beginning attempt to examine the extent to which older parents have planned for the future well-being of an offspring with serious mental illness. Significant limitations include a self-selected sample with unknown generalizability, reliance on self-report data from one family member, and a cross-sectional design that does not capture the unfolding process of planning. Future research on this important issue should encompass such topics as correlates of planning for the future, such as amount of care provided, mother's health, offspring's diagnosis and behavior problems, and perceived service need; the availability, use, and efficacy of planning services; the role of fathers and siblings in planning; barriers to professional involvement, such as lack of reimbursement for time spent with families; and the impact of public policy, such as standards for residential settings.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant to the first author from the graduate research board of the University of Maryland at College Park.

Dr. Smith is associate professor and Dr. Hatfield is professor emeritus in the department of human development at the University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Miller is a research analyst at the Education Statistics Services Institute in Washington, D.C. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America held November 20-24, 1998, in Philadelphia.

|

Table 1. Stage of residential planning by 157 mothers for their offspring with severe mental illness1

1 Percentages have been rounded

|

Table 2. Perceived degree of need for various formal services to assist with planning and use of services during the past year1

1 Cases of missing data ranged from two to four for the questionsPercentages have been rounded

1. Cook JA, Lefley HP, Pickett SA, et al: Aging and family burden among parents of offspring with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 64:435-447, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cook JA, Cohler BJ, Pickett SA, et al: Life-course and severe mental illness: implications for caregiving within the family of later life. Family Relations 46:427-436, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Cohler BJ, Pickett SA, Cook JA: The psychiatric patient grows older: issues in family care, in Aging and Caregiving. Edited by Liebowitz BE, Light E. New York, Springer, 1991Google Scholar

4. Lefley HP: Aging parents as caregivers of mentally ill adult children: an emerging social problem. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:1063-1070, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Lefley HP, Hatfield AB: Helping parental caregivers and mental health consumers cope with parental aging and loss. Psychiatric Services 50:369-375, 1999Link, Google Scholar

6. Cook JA: Who "mothers" the chronically mentally ill? Family Relations 27:42-49, 1988Google Scholar

7. Jennings J: Elderly parents as caregivers for their adult dependent children. Social Work 32:430-433, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hooyman NR, Kiyak HA: Social Gerontology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, 5th ed. Boston, Allyn & Bacon, 1999Google Scholar

9. Greenberg JS, Reenley JR, McKee D, et al: Mothers caring for an adult child with schizophrenia: the effects of subjective burden on maternal health. Family Relations 42:205-211, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Skinner EA, Steinwachs DM, Kasper JD: Family perspectives on service needs of people with serious and persistent mental illness. Innovations and Research 1(3):23-30, 1992Google Scholar

11. Lefley HP: Family Caregiving in Mental Illness. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1996Google Scholar

12. Hatfield AB: Leaving home: separation issues in psychiatric illness, in Psychological and Social Aspects of Psychiatric Disability. Edited by Spaniol L, Gagne C, Koehler M. Boston, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston University, 1997Google Scholar

13. Heller T, Factor F: Permanency planning for adults with mental retardation living with family caregivers. American Journal on Mental Retardation 96:163-176, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

14. Smith GC, Tobin SS, Fullmer EM: Elderly mothers caring at home for offspring with mental retardation: a model of permanency planning. American Journal on Mental Retardation 99:487-499, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

15. Smith GC, Tobin SS, Fullmer EM: Assisting older families of adults with lifelong disabilities, in Strengthening Aging Families: Diversity in Practice and Policy. Edited by Smith GC, Tobin SS, Robertson-Tchabo EA, et al. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1995Google Scholar

16. Hatfield AB: Serving the unserved in community rehabilitation programs, in Readings in Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Edited by Anthony W, Spaniol L. Boston, Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 1994Google Scholar

17. Green MT: Interventions for neurocognitive deficits: editor's introduction. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:197-200, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Smith GC, Fullmer EM, Tobin SS: Living outside the system: an exploration of families who do not use day programs, in Life Course Perspectives on Adulthood and Old Age. Edited by Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Janicki MP. Washington, DC, American Association on Mental Retardation, 1994Google Scholar

19. Pruchno RA, Patrick JH, Burant CJ: Aging women and their children with chronic disabilities: perceptions of sibling involvement and effects on well-being. Family Relations 45:318-326, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Marsh DT, Dickens RM: Troubled Journey: Coming to Terms With the Mental Illness of a Sibling or Parent. New York, Tarcher/Putnam, 1997Google Scholar

21. Smith GC, Tobin SS: Case managers' perceptions of practice with older parents of developmentally disabled adults, in The Elderly Caregiver: Caring for Adults With Developmental Disabilities. Edited by Roberto KA. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1993Google Scholar