Locus of Mental Health Treatment in an Integrated Service System

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Epidemiological surveys suggest that half of mental disorders in the community are treated in general medical settings. This paper examines delivery of mental health services in psychiatric, primary care, and specialty medical clinics in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the largest integrated public-sector health care system in the United States. METHODS: The study examined all outpatient visits to VA clinics between October 1996 and March 1998, a time during which VA policy promoted a shift to a primary care model. For veterans with a primary diagnosis of a mental or substance use disorder who made any visit to a VA psychiatric, primary care, or specialty medical clinic, we compared the locus of care and case mix as well as changes in treatment patterns during the study period. RESULTS: Of 437,035 veterans treated for a mental disorder during the final six months of the study period, only 7 percent were seen for their mental disorders exclusively in primary care and specialty medical clinics. Compared with veterans with mental disorders treated in specialty mental health clinics, those treated in medical clinics had less serious psychiatric diagnoses and made fewer visits. While there was a substantial shift of care from specialty to primary care during the study period, no comparable change in the distribution of care between medical and mental health settings was found. CONCLUSIONS: Treatment patterns in VA clinics differ markedly from those in the private sector. Research is needed to determine whether and how staffing models developed in HMOs and community samples should be extended to these public-sector settings.

Twenty-two years ago, Regier and colleagues (1) first described the high rates of mental health treatment delivered in general medical settings in the "de facto" U.S. mental health care system. Since then, a number of large epidemiological surveys have confirmed that in representative community samples, treatment of people with mental disorders is about as likely to occur in a general medical setting as in a specialty mental health setting (2,3).

The existence of parallel public and private mental health sectors has made it difficult to develop consistent policies that span these disparate systems (4). The public sector functions as a system of last resort for patients with persistent and severe mental illness who are uninsured or who have exhausted private insurance benefits. Patients in this system generally are both sicker and more socially disadvantaged than those seen by general community providers (5). However, the decentralized nature of state hospital and community mental health systems has made systematic study of patterns of mental health care across these organizations difficult (6).

As of 1992, 9 percent of hospitalizations and 8 percent of all mental health outpatient episodes in the United States occurred in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), making it the nation's largest integrated public-sector mental health care system (7). In 1995 the VA system began a major restructuring, which included a shift to health care treatment organized around ambulatory primary care services (8,9). Given the nature of the VA population, it was unclear whether and how these changes would affect delivery of services for mental illness.

This study examines the locus and case mix of treatment for mental illness in VA clinics across an 18-month period of rapid transformation. We sought to address two questions: First, how is mental health treatment in the VA system distributed between specialty mental health providers and general medical providers? Second, to what degree has a shift toward a primary care model changed mental health treatment patterns in the VA system?

Methods

Our sample consisted of all individuals who received a primary diagnosis of a mental disorder (ICD-9 codes 290.00 to 319.99) during at least one visit to a VA psychiatric, primary care, or specialty medical clinic during the study period, October 1996 to March 1998. We analyzed all mental health visits— clinical contacts associated with a primary diagnosis of a mental disorder as determined from ICD-9 codes using eight categories: schizophrenia (295.00 to 295.99), major depression (296.20 to 296.39), bipolar disorder (296.00 to 296.19 and 296.40 to 296.89), minor depression (300.40, 309.10, and 311.00), substance use disorders (291.00 to 292.99 and 303.00 to 305.99), anxiety disorders (300.00 to 300.09 and 300.20 to 300.29), posttraumatic stress disorder (309.81), and other psychiatric disorders (any ICD-9 code between 290.00 and 319.99 other than those listed in the other seven categories).

We conducted our analysis in three parts. First, we examined the locus of treatment for contacts in which the primary reason for the visit was a mental disorder— mental health clinics only, primary care clinics only, specialty medical clinics only, or treatment in both a mental health and a medical (primary care or specialty) setting. Second, we examined the case mix intensity of care in these clinics, as represented by the most common psychiatric diagnoses and the mean number of visits for individuals treated in each of the three types of clinic. Finally, we looked at changes over time by comparing locus of care in the first and in the final six months of the study period.

Results

Locus of treatment

Of 1,908,430 veterans who received outpatient services in the VA system during the final six months of the study period, 437,035 (22.9 percent) received a primary mental health diagnosis during at least one visit. Of this group, 403,427 (92.3 percent) received treatment for a mental disorder in mental health clinics, 58,532 (13.4 percent) in primary care clinics, and 16,888 (3.9 percent) in specialty medical clinics. As these figures imply, some patients received treatment for mental disorders in more than one setting. Only 7 percent of veterans treated for a mental health problem were treated exclusively in medical clinics. Among those treated in medical clinics, 74.6 percent were treated in primary care settings and 26.4 percent in specialty medical settings.

Case mix and intensity of care across sites

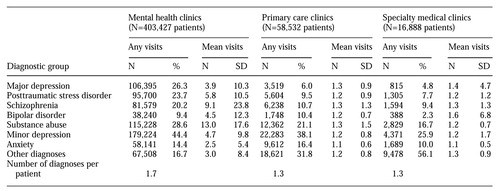

Substance abuse, anxiety, and minor depression were represented in roughly similar proportions across all clinic types (see Table 1). However, more serious disorders constituted a much larger proportion of the case mix in the mental health clinics than in the primary care or specialty clinics. Veterans diagnosed with major depression, for example, made 26.3 percent of the visits to mental health clinics, whereas they made only 5.7 percent of the visits to the primary care and specialty medical clinics.

Veterans visiting the mental health clinics also made substantially more visits for mental disorders than those seen in the medical clinics. This was particularly the case for more serious mental illnesses. For instance, veterans with schizophrenia seen in the mental health clinics made an average of 9.1 visits each for that illness in the six-month period of the study, compared with 1.3 visits for schizophrenia in the medical clinics. Patients seen in the mental health clinics were diagnosed as having an average of 1.7 different mental health diagnoses during the six-month period, compared with 1.3 different diagnoses for those seen in the primary care and specialty clinics.

Changes in locus of carefrom 1996 to 1998

Between 1996 and 1998 there was a pronounced shift from specialty to primary care clinics in the VA health care system. During that period an increase in the number of patients making only a primary care visit (51.7 percent versus 56.9 percent; χ2=10,352, df=1, p>.001) paralleled a decrease in those making visits only to medical specialty clinics (38.1 percent versus 32.4 percent; χ2=13,523, df=1, p>.001).

This shift from specialty to primary care clinics also occurred among patients being treated for mental disorders. Between 1996 and 1998, the number of visits these patients made to primary care facilities increased (from 4.3 percent to 5 percent; χ2= 242, df=1, p>.001), while the number of visits they made to specialty medical clinics decreased (from 2.5 percent to 1.7 percent; χ2=680, df=1, p>.001). However, no change occurred in the number of patients receiving care in the primary care and specialty medical clinics compared with those receiving care in mental health clinics (17 percent and 16.9 percent, respectively).

Conclusions

The vast majority of patients diagnosed with mental disorders in VA outpatient clinics receive treatment for those disorders in mental health clinics rather than in medical settings. This pattern stands in marked contrast to that reported for community and private-sector samples, in which the distribution is more evenly divided between medical and specialty mental health settings. Even during a time when VA policy was shifting patients from specialty medical clinics to primary care providers, there was no corresponding redistribution of patients from mental health clinics to medical settings.

In considering the implications of our findings, two limitations should be borne in mind. First, in the administrative data used in this study we can identify those who have been diagnosed as having or who have been treated for a given illness, but we cannot determine the true prevalence of that illness (10). Because a substantial portion of mental illness goes undetected and untreated in medical settings (11), the findings most likely underestimate the prevalence of mental disorders in those clinics. Second, limited data were available on severity of mental or medical illness across settings. Thus the lower rate of mental health care delivery in medical settings might reflect lower psychiatric morbidity, differing provider practice patterns, or a combination of the two.

It is likely that the reliance in the VA system on specialty mental health providers is due at least in part to the high psychiatric morbidity in the VA population. Patients in VA facilities, as in other public-sector settings, commonly present with illnesses that are chronic, severe, and compounded by social disability (12). "Benchmarking" estimates of staffing needs based on patterns in health maintenance organizations (HMOs) may have limited generalizability to these public-sector settings (13).

However, if differences in treatment are related primarily to practice variations between the public and private sectors or between mental health and general medical providers, then it is essential to develop and test systems that can successfully optimize mental health outcomes in these settings. In HMOs, successful treatment of mental disorders by primary care physicians has been found to involve a combination of patient education, outcomes assessment, and access to psychiatric consultation (14). Further research is needed to determine whether, or how, these models can be extended to the public sector.

Acknowledgment

This paper was funded in part by National Institute of Mental Health grant K08-MH-01556-01.

Dr. Druss and Dr. Rosenheck are affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System and the departments of psychiatry and public health at Yale University. Address correspondence to Dr. Druss, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 950 Campbell Avenue (116A), West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Case mix and intensity of outpatient care across treatment settings in the VA system in 1998

1. Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Taube CA: The de facto US mental health services system: a public health perspective. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:685-693, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sharfstein SS, Stoline AM, Goldman HH: Psychiatric care and health insurance reform. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:7-18, 1993Link, Google Scholar

5. Surles RC, Shore MF: The public sector-private sector interface: current issues, future trends. New Directions in Mental Health Services, no 72:71-79, 1996Google Scholar

6. Hansson L, Sandlund M: Utilization and patterns of care in comprehensive psychiatric care organizations: a review of studies and some methodological considerations. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 86:255-261, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Redlick RW, Witkin MJ, Atay JE, et al: Highlights of organized mental health services in 1992 and major national and state trends, in Mental Health, United States, 1996. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. DHHS pub (SMA)96-3098. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1996Google Scholar

8. Kizer KW: Transforming the veterans health care system: the "new VA." JAMA 275:1069, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Iglehart JK: Reform of the Veterans Affairs health care system. New England Journal of Medicine 335:1407-1411, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Unützer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, et al: The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder in a large staff-model HMO. Psychiatric Services 49:1072-1078, 1998Link, Google Scholar

11. Simon GE, VonKorff M: Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Archives of Family Medicine 4:99-105, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wilson NJ, Kizer KW: The VA health care system: an unrecognized national safety net. Health Affairs 16(4):200-204, 1997Google Scholar

13. Dial TH, Bergsten C, Haviland MG, et al: Psychiatrist and nonphysician mental health provider staffing levels in health maintenance organizations. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:405-408, 1998Link, Google Scholar

14. Simon GE: Can depression be managed appropriately in primary care? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(suppl 2):3-8, 1998Google Scholar