Psychiatrist and Nonphysician Mental Health Provider Staffing Levels in Health Maintenance Organizations

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study attempts to determine the ratio of full-time-equivalent psychiatrists to members and that of nonphysician mental health professionals to psychiatrists in staff and group model health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and to compare the psychiatrist-to-member ratio with previous estimates of the required psychiatrist-to-population ratios in fee-for-service and managed care environments. METHOD: The Group Health Association of America (now the American Association of Health Plans) collected data on mental health staffing, enrollments, and other characteristics for 30 staff and group model HMOs. The authors evaluated the number of full-time-equivalent psychiatrists and nonphysician mental health professionals per 100,000 HMO members, and the ratio of full-time-equivalent nonphysician mental health professionals to psychiatrists. RESULTS: The overall mean number of full-time-equivalent psychiatrists and nonphysician mental health professionals per 100,000 members in the responding HMOs was 6.8 and 22.9, respectively. The overall mean ratio of nonphysician professionals to psychiatrists was 4.5. The overall number of psychiatrists per 100,000 members is less than half the requirement estimated by the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee in 1980, which assumed a fee-for-service environment, but it is about 40% to 80% greater than that estimated by other studies under the assumption of a managed care environment. CONCLUSIONS: Although a practice environment dominated by managed care may not require as high a psychiatrist-to-population ratio as a predominantly fee-for-service environment, it may well support a greater number of psychiatrists than previous studies have suggested.

The physician need projections made in 1980 by the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee (GMENAC) (1) assumed a fee-for-service reimbursement environment, and the estimates generally are considerably higher than estimates of the number of physicians required in a managed care environment (2–4). The Association of American Medical Colleges, the Institute of Medicine, and the Pew Health Professions Commission say fewer physicians are needed to care for the population as managed care expands, and plans are being made to head off what some say could be a large physician surplus (5–8). This issue is especially relevant for psychiatrists. The GMENAC estimate of the need for psychiatrists in a fee-for-service environment was 15.8 full-time-equivalent psychiatrists per 100,000 population (1), whereas managed care estimates have ranged from 3.8 to 4.8 per 100,000 (2, 4).

Over the past decade, concerns about controlling the cost of care for mental illness and substance abuse have led to a careful scrutiny of mental health benefits and coverage limits (9, 10), and to reevaluations of the role and training of psychiatrists (11). Health maintenance organizations (HMOs) have been viewed by health care industry analysts as one way to balance the demand for mental health services with the need to control costs.

From late 1993 through early 1994, the Group Health Association of American (GHAA, now the American Association of Health Plans) initiated a study to describe clinical staffing patterns in a relatively large, representative sample of staff and group model HMOs (12). In general, providers affiliated with a staff or group model HMO work exclusively for the HMO. This distinguishes those models from the independent practice association (IPA) and network models, where providers affiliated with the HMO may treat patients enrolled in other health plans. Staff and group model HMOs were chosen because they can provide accurate data on both staffing and the populations they serve, they provide comprehensive care, and they use an efficient mix of generalists and specialists.

METHOD

Project staff mailed the clinical staffing survey in December 1993 to medical directors of all 106 GHAA-member HMOs that were either entirely or predominantly staff or group models. Fifty-eight HMOs responded, yielding a 54.7% response rate. Four responses that identified their predominant model type as either network or independent practice association were excluded from the survey results. The data collected included numbers of full-time-equivalent physicians and nonphysician health care providers, overall and by specialty or profession. The categories of nonphysician mental health professionals were licensed clinical psychologist, licensed social worker, and psychiatric clinical nurse specialist. Respondents were asked to exclude hospital-based providers from their counts of both full-time-equivalent physicians and nonphysicians, and no data were obtained on providers outside the networks of HMOs, to whom HMO members might go and pay out-of-pocket for care. We examined enrollment-weighted means, standard deviations, and quartiles to describe physician and nonphysician staffing patterns and how they vary by model type and size. An enrollment-weighted provider-to-member ratio is a ratio of all the providers in the responding HMOs to all the members in those HMOs. It is thus analogous to an overall provider-to-population ratio. To compare means (staff versus group model and small versus large HMOs), we used the Mann-Whitney U test.

RESULTS

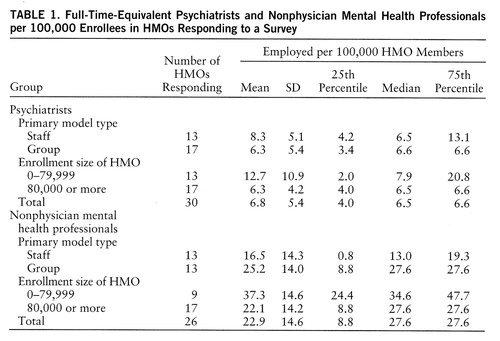

Fifty of the 54 HMOs provided usable data on the number of full-time-equivalent primary care physicians, 30 provided usable data on the total number of full-time-equivalent psychiatrists on staff or under contract, and 26 provided full-time-equivalent data on nonphysician mental health providers.

Table 1 presents total number of full-time-equivalent psychiatrists per 100,000 HMO members. The overall enrollment-weighted mean ratio was 6.8. The differences between small (fewer than 80,000 members) and large (80,000 or more members) and between staff and group model HMOs were not statistically significant at the p=0.05 level.

Table 1 also presents total number of full-time-equivalent nonphysician psychiatric professionals per 100,000 members. The overall enrollment-weighted ratio was 22.9. This ratio also failed to differ significantly between small and large HMOs, and between the staff and group models.

= The mean weighted ratio of nonphysician psychiatric professionals to psychiatrists was 4.5 to 1 (table 2). The ratio in smaller HMOs was significantly higher than that in larger HMOs (Mann-Whitney U=36, p=0.03).

Table 3 compares the observed number of psychiatrists per 100,000 staff and group model HMO members to three estimates of psychiatrist-to-population requirements and to the actual number of psychiatrists per 100,000 in the United States in 1994. The number of psychiatrists per 100,000 HMO members is less than half the requirement estimated by GMENAC, which assumed a fee-for-service environment, and is substantially lower than the existing nationwide ratio of 12.6 patient care psychiatrists per 100,000 population (13). It is, however, about 40% to 80% greater than the ratio that has been estimated by other studies under the assumption of a managed care environment (2, 4).

DISCUSSION

To understand the implications of these data for health workforce policy, it is essential to consider them in a broader context. Psychiatric staffing levels in closed-panel HMOs do not provide the full picture and, taken alone, are not a satisfactory basis for projecting the demand for psychiatrists' services by the entire population.

Existing models to predict future needs for psychiatrists lead to contradictory estimates. Need-based approaches, which rely on estimates from epidemiologic studies, typically suggest that there is a severe shortage of psychiatrists, and especially child psychiatrists. Need-based models do not, however, take into account society's willingness to allocate resources to fill that need.

Demand-based approaches, in principle, are more likely to accurately estimate the number of psychiatrists the society will support. Lacking valid methods to directly measure demand, such approaches typically have used existing utilization patterns to estimate it. A related approach to estimating need, which has been called “benchmarking,” relies on the ratio of psychiatrists to population in certain geographic areas or market sectors (14). Although this method has its limits, it permits some informative comparisons to be made. For example, the overall psychiatrist-to-population ratio is higher in the United States than anywhere else in the world, even in countries that have full-service national health insurance with comprehensive coverage for psychiatric illnesses.

To analyze the future demand for psychiatrists, it is useful to divide the mental health care market into four sectors, each with its own demand dynamics:

1. The out-of-pocket sector. This sector's size is unknown, but it probably is large. It includes upper-income people who choose to pay directly for care and those who are without insurance and outside the public system. The demand for psychiatrists in this market segment is related to the number of highly educated people with high levels of discretionary income. Other sources of demand in this sector are those unemployed, between jobs, or without employer coverage for mental health care, those whose health insurance does not cover desired services, and those who choose not to use their insurance coverage for mental health services, sometimes because of concern about confidentiality (15). It is difficult to say whether this sector is growing, and even more difficult to estimate the number of psychiatrists it can support. The number of U.S. households with annual income over $75,000 (in constant 1993 dollars) increased from about 9.4 million to about 12.1 million between 1985 and 1993 (16). On the other hand, out-of-pocket payments have been shrinking steadily as a percentage of all health care expenditures for more than 30 years (17). The uninsured have increased in number since the 1980s (18), but they frequently forgo needed care because they cannot afford it (19).

2. The public sector. This was the other major component of the market for psychiatric services before the 1960s, existing initially in state hospitals and later expanding into public community settings. The demand generated by this sector is a function of the apportionment of public funds to mental health care and specifically to psychiatric services. The level of funding in the public sector varies considerably from state to state, and may not coincide with the amount and degree of psychiatric morbidity presenting to public settings.

3. The indemnity insurance sector. From the 1960s into the 1980s the growth of indemnity health insurance, including Medicare, Medicaid, and employer-sponsored coverage, expanded the demand for the services of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. The overall size of the indemnity sector has decreased rapidly in recent years as the fourth sector, managed care, has grown. Moreover, utilization review and precertification requirements have increased to the point that completely “unmanaged” indemnity coverage has all but disappeared, at least from private health insurance. Managed care is now beginning to make inroads into Medicare and Medicaid as well.

4. The managed care sector. In this sector, allocation of resources to purchase psychiatric services is subject to organizational, financial, and procedural efforts to make the delivery of mental health care more efficient. The data presented here provide a picture of mental health staffing in one part of the managed care sector. There are many unanswered questions about the number of physicians needed in HMOs and other kinds of health plans. Estimates based on this sector do not include the use of out-of-plan providers. Nevertheless, the consensus of observers is that psychiatrist-to-population ratios (like other specialist-to-population ratios) are lower in a managed care environment than in a fee-for-service system.

Other developments, such as pharmacological advances and the changing responsibilities of primary care providers, may affect psychiatrists' efficiency and roles. The ways in which managed care organizations use nonphysician mental health professionals may be another critical factor to consider when projecting future requirements for psychiatric services. The findings presented here are congruent with previous studies that cite the important role of nonphysician mental health professionals in the managed care sector. In this study, the mean ratio of nonphysician psychiatric professionals to psychiatrists was 4.5.

Future psychiatrist-to-population ratios may approach those seen today in staff and group model HMOs, or they may be somewhere between these levels and those estimated by GMENAC in a fee-for-service environment. It seems unlikely, however, that future demand for psychiatric services will be as high, relative to the size of the population, as it was before the managed care revolution. On the other hand, if there are almost seven full-time-equivalent psychiatrists in HMO networks for every 100,000 members, it also seems unlikely that the total demand for psychiatrists will be as low as four or five per 100,000. Given the uncertainty about the demand side, it is critical that the dynamics of the supply side be understood.

The challenges to psychiatry are great. The enormous changes in the health care system, and the effects of those changes on the role of psychiatrists in the treatment of mental and addictive disorders (10, 11), may be fueling U.S. medical graduates' declining interest in psychiatry (20), despite the generally good employment opportunities for psychiatrists (21, 22). For several years psychiatry has relied heavily on international medical graduates to fill U.S. residency slots (23). Narrow definitions of the role of psychiatry and calls to restrict the access of international medical graduates to U.S. residency slots may have unintended consequences, given the uncertainties of estimates of the demand and need for psychiatrists. Efforts need to be undertaken to better estimate how changes in the residency pool affect the steady state of the overall supply of psychiatrists. Without adequate projections of the influence of supply side changes, the number of psychiatric residents may fall too quickly, for the wrong reasons, and too far. If adjustments are made on the basis of the lowest estimates of demand in a managed care environment, the resulting numbers may undershoot the mark by a wide margin.

|

|

|

Received Dec. 26, 1996; revisions received June 25 and Sept. 16, 1997; accepted Oct. 17, 1997. From the Department of Psychiatry, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, Calif., and the American Association of Health Plans and the American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C. Address reprint requests to Dr. Dial, National Education Association, 1201 16th St., N.W., Washington, DC 20036; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Summary Report of the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee to the Secretary, Department of Health and Human Services, vol I: DHHS Publication HRA 81-651. Washington, DC, US DHHS, Sept 30, 1980Google Scholar

2. Mulhausen R, McGee J: Physician need: an alternative projection from a study of large, prepaid group practices. JAMA 1989; 261:1930–1934Google Scholar

3. Sauve M: Reassessing the number and mix of system physicians needed. Healthcare Financial Management 1996; 50:56–62Medline, Google Scholar

4. Weiner JP: Forecasting the effects of health reform on US physician workforce requirement: evidence from HMO staffing patterns. JAMA 1994; 272:222–230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Cohen J: The right guidelines for right-sizing residencies. Acad Med 1996; 71:480Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Cohen JJ: Too many doctors: a prescription for bad medicine. Acad Med 1996; 71:564Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Institute of Medicine: The Nation's Physician Workforce: Options for Balancing Supply Requirements. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1996Google Scholar

8. Pew Health Professions Commission: Critical Challenges: Revitalizing the Health Care Professions for the Twenty-First Century. San Francisco, University of California, San Francisco, Center for the Health Professions, 1995Google Scholar

9. Anderson DF, Berlant JL: Managed mental health and substance abuse services, in The Managed Health Care Handbook. Edited by Kongstvedt PR. Gaithersburg, Md, Aspen, 1993, pp 130–141Google Scholar

10. Boyle PJ, Callahan D: Managed care in mental health: the ethical issues. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995; 14:7–22Medline, Google Scholar

11. Meyer RE, Sotsky SM: Managed care and the role and training of psychiatrists. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995; 14:65–77Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Dial TH, Palsbo SE, Bergsten C, Gabel JR, Weiner J: Clinical staffing in staff- and group-model HMOs. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995; 14:168–180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. American Medical Association: Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US, 1995–96 edition. Chicago, AMA, 1996Google Scholar

14. Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Bubols TA, Mohr JE, Poage JF, Wennberg JE: Benchmarking the US physician workforce. JAMA 1996; 276:1811–1817Google Scholar

15. Pincus HA, Zarin D, West JC: Peering into the “black box.” Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:870–877Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. US Bureau of the Census: Statistical Abstract 1995, 115th ed. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1995, p 469Google Scholar

17. Reilly P: New national health expenditure data released. Milliman & Robertson Health Cost Index Report 1996; 9(3):4–6Google Scholar

18. Employee Benefits Research Institute: Sources of Health Insurance and Characteristics of the Uninsured: EBRI Issue Brief number 170. Washington, DC, EBRI, 1996Google Scholar

19. Donelan K, Blendon RJ, Hill CA, Hoffman C, Rowland D, Frankel M, Altman D: Whatever happened to the health insurance crisis in the United States? JAMA 1996; 276:1346–1350Google Scholar

20. Weissman S: Recruitment and workforce issues in late 20th century American psychiatry. Psychiatr Q 1996; 67:125–137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Miller RS, Jonas HS, Whitcomb ME: The initial employment status of physicians completing training in 1994. JAMA 1996; 275:708–712Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Miller RS, Dunn MR, Whitcomb ME: Initial employment status of resident physicians completing training in 1995. JAMA 1997; 277:1699–1704Google Scholar

23. National Residency Matching Program: NRMP Data April 1997. Washington, DC, NRMP, 1997Google Scholar