Competence to Consent to Research Among Long-Stay Inpatients With Chronic Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Questions have been posed about the competence of persons with serious mental illness to consent to participate in clinical research. This study compared competence-related abilities of hospitalized persons with schizophrenia with those of a comparison sample of persons from the community who had never had a psychiatric hospitalization. METHODS: The study participants were administered the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR), a structured instrument designed to aid in the assessment of competence to consent to clinical research. The scores of 27 persons who met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia who were long-stay patients on a state hospital research ward were compared with those of 24 individuals from the community who were of similar age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status. RESULTS: Significant differences were found between the patients and the community sample on three measures of competence-related abilities: understanding, reasoning, and appreciation. Degree of psychopathology and cognitive functioning were significantly negatively correlated with understanding and appreciation among the patients with schizophrenia. Length of hospitalization was significantly negatively correlated with all measures of decision-making capacities. CONCLUSIONS: The generally poor performance of the long-stay patients with chronic schizophrenia highlights the difficulties this group is likely to encounter in providing consent to research. However, variation across the sample points to the need for individualized assessment and for validated techniques for facilitating decision making in the face of decisional impairments.

Informed consent is generally a prerequisite for participation in clinical research (1). Federal regulations have assigned responsibility for oversight of the consent process to institutional review boards (2). However, institutional review boards do not approach this task in a uniform manner, and external guidance is frequently lacking, leading many observers to conclude that the interests of research participants may not always be protected (3).

Concern is particularly acute in the case of study participants who suffer from disorders that may impair their cognitive functioning. Such impairment can compromise participants' abilities to protect their best interests, which makes it even more important to provide meaningful oversight. Yet many researchers fear that if stringent rules were put into effect to regulate such research, important investigations—including those whose methodologic and ethical soundness is unquestioned—would be hampered (4).

Attention has been drawn to this issue by recent high-profile cases that have cast a cloud over research among persons with mental illness, including persons with schizophrenia (5,6). This development is unfortunate, because research on the etiology and treatment of this disorder is badly needed. Although there have been discussions about possible alternatives to obtaining consent from research participants who are not competent to make decisions—for example, greater accessibility of surrogate procedures (7)—and about how to provide closer supervision of research, the degree to which patients with schizophrenia lack the capacity to make their own decisions about research participation remains unclear.

Data from studies of treatment decision making by patients with schizophrenia have suggested that, as a group, these patients perform significantly worse on many measures than do patients with depression; patients with other medical illnesses, including heart disease and HIV infection; and healthy comparison subjects (8,9,10). The first study of decision making relating to research participation that carefully examined decisional capacity confirmed that long-stay inpatients with schizophrenia who did not respond to treatment performed significantly more poorly than a healthy comparison group (11). However, the study also suggested that educational interventions might be able to bring most patients to an acceptable level of performance (11), a finding that was reflected in other studies (12,13). It is also clear that patients with schizophrenia display wide variation in their performance (11,14). In addition, one study suggested that, whatever their impairments, patients with schizophrenia generally retain adequate capacity to differentiate among studies that differ in their risk-benefit ratios (15).

A key determinant of the need for additional protections for potential research participants with schizophrenia is the degree to which their decisional abilities differ from those of the general population. In this study we aimed to augment the limited body of data on this subject by comparing the performance of research participants with schizophrenia with that of a comparison group of persons from the community who were not mentally ill. For this purpose, we used the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR) (16), which has been used in a number of studies of persons with disorders that may impair decisional capacity (10,11,14,17,18).

Methods

Participants

Data were contemporaneously collected from a sample of 27 psychiatric inpatients and 24 individuals from the community during the period January through June 1996. The psychiatric inpatient sample was drawn from patients who were admitted to a research unit at Western State Hospital in Staunton, Virginia. The 30-bed clinical studies unit was established in the 1980s at Western State Hospital in affiliation with the University of Virginia to facilitate intensive assessment, improve treatment, and establish research for patients with severe mental illness. The primary areas of research have been polydipsia and intermittent hyponatremia and clinical psychopharmacology trials.

Admission to the research unit was based on the criteria of ongoing studies conducted there. Clinicians' perceptions of patients' competence played no role in selection. All patients admitted to the research unit were long-stay patients at the hospital, and none were acutely ill. All of those who were between the ages of 18 and 65 years and who had primary diagnoses of DSM-IV schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were eligible for inclusion in this study. Patients who had concomitant diagnoses of mental retardation and those who had suffered traumatic brain injury were not eligible to participate. Of 42 eligible patients, 14 (33 percent) refused to participate. The protocol for this study was approved by the institutional review board at Western State Hospital in Staunton Virginia.

The comparison sample was recruited from the community at a variety of sites, including community centers and a free medical clinic. These individuals were selected to provide a group match with the inpatient sample in terms of socioeconomic status, age, race, and gender. Potential comparison subjects were excluded if they reported any past psychiatric hospitalizations or if it was determined that they had a diagnosis of schizophrenia on the basis of the administration of the schizophrenia module of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule Screening Interview (DISSI) (19). A total of 24 persons were recruited for the comparison group. Several people who were approached declined to participate in the study. Only one person dropped out after initially agreeing to participate. Data from this comparison group have been reported previously (11).

Measures

The MacCAT-CR. The MacCAT-CR is based on a similar tool designed to aid in the assessment of competence to consent to treatment (20), derived in turn from research instruments used in a multisite study of decision-making capacities of persons with mental and medical illnesses (8,21,22). The MacCAT-CR provides a semistructured interview format with which to assess and rate the abilities of potential research participants according to the four most commonly accepted components of decision-making competence in clinical settings (23,24): understanding of disclosed information about the nature of the research project and its procedures; reasoning about participation, focusing on participants' abilities to compare alternatives in light of their consequences; appreciation of the effects of research participation—or nonparticipation—on the participant's own situation; and communication of a decision about participation. Because all participants in this study had to be able to communicate a choice to participate, scores on this part of the instrument were not analyzed. Three of the inpatients and two members of the comparison group received less than full credit on the measure of expressing a choice. This result was generally due to ambivalence and was not thought to be a significant difference.

The MacCAT-CR format can be individualized to ask questions about a particular research project or, as in the case of this study, can describe a hypothetical project. In this study, the MacCAT-CR described a hypothetical clinical trial of a new medication for schizophrenia that was being conducted in a randomized, double-blind fashion. This version of the MacCAT-CR was substantially similar to one used among persons with schizophrenia in a previous study (11). Selected information about the hypothetical study was disclosed, and a standard set of questions was asked to sample the participants' abilities.

The MacCAT-CR is scored on the basis of standardized criteria. Each question is scored on a scale of 0 to 2, with each component scale having the following possible ranges: understanding, 0 to 26; reasoning, 0 to 8; and appreciation, 0 to 6. Higher scores indicate greater understanding, reasoning, and appreciation. To provide a measure of interrater reliability in this study, ten completed protocols were scored by the interviewer and then independently scored by a second rater, a senior research staff member who had served as "master scorer" in a previous study of competence (25). Kappas calculated on the measures of understanding, reasoning, and appreciation were .69, .53, and .79, respectively.

Chart data. Information on inpatients' race, diagnosis, and admission date were obtained from hospital charts.

Background interview data. A brief interview derived from one used in previous competence research (8) was used to obtain information from potential comparison subjects about past psychiatric history.

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) is an interview-based measure of psychopathology that was used to identify symptom patterns that may correlate with increased pathology (26). The severity of signs and symptoms of mental illness are rated on a 7-point Likert scale. The 18 items can be summed to provide a global measure of the severity of psychopathology, and can be used to generate several generally accepted subscales (27).

Verbal cognitive functioning. Three subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R)—vocabulary, similarities, and digit span—were used to generate a measure of study participants' cognitive abilities at the time of the research interview. Verbal cognitive functioning was calculated by using the WAIS-R norms to convert subtest raw scores to scaled scores, which were summed and multiplied by 2. WAIS-R age-normed tables were used to convert the resulting sum to the equivalent of a pro-rated verbal IQ score. This procedure yields scores that are highly correlated (r>.90) with WAIS-R verbal IQ (28). Because cognitive functions are likely to be impaired by mental illness, in this study we regarded verbal cognitive functioning as an index of current verbal cognitive functioning and not of baseline intellectual functioning.

Procedure

Patients who met the inclusion criteria were approached by one of the authors (RL), who explained the nature of the study and obtained written informed consent. This investigator also made a clinical judgment as to whether the patient was competent to participate in this study (no instrument was used for this purpose), applying a low threshold standard because of the minimal risk involved. This approach was consistent with prevailing standards at the time of the study. In one case, a patient who agreed to participate in the study was thought to be incompetent to consent, and an authorized representative (akin to a guardian) consented to participate on that person's behalf. (Under regulations governing state mental hospitals in Virginia, "authorized representatives" may be designated to make decisions on behalf of patients who are incompetent to do so.)

Another member of the study team (JAK), blinded to the consent process, administered the research instruments to both groups. This researcher was also the sole recruiter of the comparison group.

In responding to the MacCAT-CR, the patients were instructed to assume that they were being asked to consider participating in a research study of a new medication for the treatment of schizophrenia. Members of the comparison group were given the same protocol and instructed to assume that they suffered from schizophrenia, a serious mental disorder. The nature of the disorder is briefly reviewed as part of the MacCAT-CR procedure. These comparison subjects were not expected to understand the depth of impairment often associated with schizophrenia. They were told to answer the questions from their own point of view, not as they would expect a person with schizophrenia would answer. All study participants were paid $10.

Results

Sample description

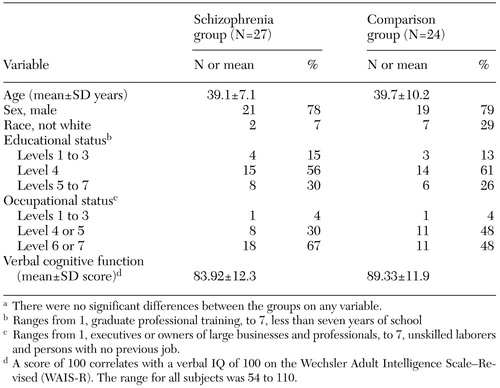

The patient group and the comparison group were compared on age, gender, race, and two components of socioeconomic status—highest educational level and highest occupational level ever achieved (29). The education scale ranges from 1 (graduate professional training) to 7 (less than seven years of school). Similarly, the occupational scale ranges from 1 (executives, owners of large businesses, and professionals) to 7 (unskilled laborers or no past job). In addition, verbal cognitive functioning was measured for both groups (Table 1).

The BPRS (severity of psychiatric symptoms) was administered to the patients with schizophrenia. The mean±SD BPRS score was 42.7± 11.87, indicating a substantial level of psychopathology. The two groups were well matched on demographic characteristics, and no significant differences were found between the patient group and the comparison group on any of those variables. Verbal cognitive functioning was not significantly different between the two groups. The patients constituted a chronically hospitalized sample, with a mean length of hospitalizations of 2,686± 1,710 days (approximately seven years and four months) and a range of 67 to 7,375 days.

Performance on the MacCAT-CR

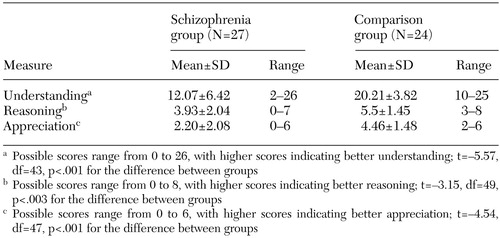

As can be seen in Table 2, the group of inpatients with schizophrenia performed more poorly on the measures of competence than did the comparison group from the community, obtaining significantly lower scores on measures of understanding, reasoning, and appreciation.

There is currently no standard way to determine where to set the cutoff for adequacy of performance on any of these measures. We chose a conservative cutoff in defining adequacy of performance: a score equal to or better than that of the worst-performing comparison subject. We calculated the proportion of patients with schizophrenia who received a score below the lowest of the comparison subjects' scores on the measures of understanding, reasoning, and appreciation. The range of total scores for the patients with schizophrenia was 2 to 26 for understanding, 0 to 7 for reasoning, and 0 to 6 for appreciation. The corresponding ranges for the comparison group were 10 to 25, 2 to 6, and 3 to 8. For understanding, 11 of the patients (41 percent) obtained a score below that of the lowest-scoring comparison subject. The percentages for reasoning and appreciation were 33 percent (N=9) and 48 percent (N=13), respectively.

We then assessed the proportion of the patients with schizophrenia who received a score below that of the lowest-scoring comparison subject on at least one of the three scales. Eighteen of the patients with schizophrenia (67 percent) performed inadequately on at least one of the measures of competence-related capacities; conversely, nine (33 percent) of the patients with schizophrenia scored at least as well as the lowest-scoring comparison subject on each of the subscales. Twenty-four of the patients with schizophrenia (89 percent) obtained a score above or equal to that of the lowest-scoring comparison subject on at least one of the subscales.

Correlates of performance on the MacCAT-CR

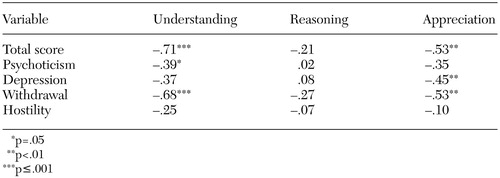

Psychopathology. As can be seen in Table 3, total BPRS score was significantly negatively correlated with understanding and appreciation among the patients with schizophrenia. Although the relationship between total BPRS score and reasoning was not significant, it did run in the expected direction—that is, greater psychopathology correlated with higher levels of impairment on decision-making tasks. We also looked at four subscales of the BPRS. A particularly strong negative correlation was noted between withdrawal and both understanding and appreciation. With the exception of two of the reasoning subscales, all the relationships were again in the expected negative direction.

In addition, we assessed whether length of hospitalization—which may be a proxy for the degree of deficit associated with the disorder—was correlated with the measures of decision-making abilities examined. A significant negative correlation (Pearson's r) was observed between the length of hospitalization and all three measures of decision-making abilities (N=27; understanding, r=−.63, p<.001; reasoning, r=−.32, p<.03; appreciation, r=−.62, p<.001).

Verbal cognitive functioning. We assessed the extent to which verbal cognitive functioning was correlated with understanding, reasoning, and appreciation. Usable data were available for 26 of the 27 patients with schizophrenia and for all 24 persons in the community sample. For the patients, verbal cognitive functioning was significantly correlated (Pearson's r) with understanding (r=.69, p<.001) and appreciation (r=.66, p<.001). However, the relationship with reasoning, although showing a similar trend, fell short of statistical significance. For the comparison group, verbal cognitive functioning was significantly correlated with understanding (r=.72, p<.001) and appreciation (r=.67, p<.001). Verbal cognitive functioning was not correlated with reasoning in the comparison group.

Discussion and conclusions

From a human rights perspective, it is critical to ensure that adequate informed consent is obtained from patients with mental illness before they are enrolled in research (4). From a research perspective, it is often desirable to involve the patients who have more refractory and chronic illness—for example, to test treatment efficacy or to explore the pathophysiology of the disorder (30). Our objective in the study reported here was to determine the extent to which patients with schizophrenia manifest deficits in legally relevant abilities to make decisions about participating in research relative to persons from the community who do not have schizophrenia.

Using the MacCAT-CR, we found significant differences between patients and a community comparison group on the three components of competence-related abilities. The two groups differed significantly in their capacity to understand the nature of research and its procedures, appreciate how their participation or lack of participation might affect their personal situation, and reason about whether to participate in the study. Two-thirds of the patients performed below the level of the lowest-scoring comparison subject on at least one scale of competence-related abilities. This group performed more poorly compared with the comparison group than did patients with schizophrenia in previous studies, including one that used the same comparison group (11).

The reasons for this variation in performance are not entirely evident but may relate to differences in the composition of these relatively small samples. Nonetheless, even in a vulnerable population such as this group of chronically hospitalized patients with schizophrenia, many of the patients (33 percent) performed as well as the comparison group. Similar results have been found when persons with mental illness have been compared directly with persons with other disorders—that is, a substantial proportion of persons with serious mental illness perform as well as members of those other groups (8,9,10). Thus neither the diagnosis of schizophrenia nor a lengthy hospitalization necessarily implies that a person lacks the requisite capacity to make decisions and give informed consent to participate in research.

Our findings on the correlates of poor performance on the MacCAT-CR both echo and differ from the results of earlier studies. Overall psychopathology, measured by the BPRS, correlated with deficits in understanding and appreciation, a finding similar to that of Moser and colleagues (10) but in contrast to that of Carpenter and colleagues (11), who found that only reasoning was related to total BPRS scores. Again, these differences could be accounted for by the heterogeneity of persons with schizophrenia or the relatively small samples. Psychotic symptoms correlated modestly with understanding, but negative symptoms were the strongest predictors of poor understanding and appreciation, the latter finding confirming the data from the study of Moser and colleagues (10). Finally, as both previous MacCAT-CR studies with persons with schizophrenia have suggested, cognitive impairment—here measured by three WAIS subscales—is the most robust predictor of impairment in decisional capacity (10,11).

The substantial levels of impairment that we found suggest that screening prospective research participants from this population may well be helpful in ensuring a pool of participants who can provide adequate consent. During such screening, the same cautions would apply as in any competence assessment task, including the importance of paying attention to cultural issues and their effect on performance. Study participants who score poorly do not necessarily have to be excluded from research protocols. Many participants may benefit from an intensive educational process or other aids to comprehension of consent-related information (11,13,31). However, for some patients it will probably be necessary for consent to be given by a substitute decision maker to enable their inclusion in a study.

As in previous studies (10,11,14,17,18), the MacCAT-CR appeared to be a useful tool for screening patients for potential participation in a research study. We found that it could be scored with acceptable levels of reliability and that it offered ease of use and scoring. The option of adapting the MacCAT-CR to particular research studies or using it to examine reactions to hypothetical studies makes it a flexible instrument both for studying cognitively impaired populations and for evaluating the process of obtaining consent to research. The validity of the MacCAT-CR was supported by correlations that were generally in the expected direction with measures of psychopathology and verbal cognitive functioning. Of interest, the weakest correlations were with the reasoning component of the measure, which also was the least reliably scored.

This was a small study of a particular subset of patients with schizophrenia: those chronically residing in a state hospital. Of necessity, we used an arbitrary cutoff to define adequacy of performance. Other researchers have used clinical raters to establish a standard of competence (18) or have established cutoffs based on the statistical performance of the pool of study participants (8). Our method, however, yielded a very conservative standard for estimating the rate of decisional incapacity, a category that should be kept as narrow as possible in a democratic polity.

Even so, with a very conservative measure for our threshold, a substantial proportion of the patients with schizophrenia in our study fell within the impaired range. In less severely ill populations one would expect that the differences between study participants with and without schizophrenia would be smaller. However, the level of performance of such participants and of persons with other psychiatric diagnoses remains an open issue requiring further examination. The development of reliable means of measuring consent-related capacities, however, should facilitate the generation of answers to these and other questions.

Dr. Kovnick is in private practice of adult, adolescent, and child psychiatry in Salt Lake City. Dr. Appelbaum is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester. Dr. Hoge is president of Life-Pool L.L.C. in Charlottesville, Virginia. Dr. Leadbetter is an adjunct faculty member at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Send correspondence to Dr. Appelbaum at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester, Massachusetts 01655 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of a sample of inpatients with schizophrenia and a comparison group drawn from the communitya

a There were no significant differences between the groups on any variable.

|

Table 2. Performance on measures of competence to participate in a research study among inpatients with schizophrenia and a comparison group from the community

|

Table 3. Correlation (Pearson's r) of scores on subscales of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale with understanding, reasoning, and appreciation in a sample of 27 inpatientswith schizophrenia

1. Berg JW, Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, et al: Informed Consent: Legal Theory and Clinical Practice, 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001Google Scholar

2. Dresser R: Mentally disabled research subjects: the enduring policy issues. JAMA 276:67–72, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Research Involving Persons With Mental Disorders That May Affect Decisionmaking Capacity: Vol 1: Report and Recommendations. Rockville, Md, National Bioethics Advisory Commission, 1998Google Scholar

4. Bonnie RJ: Research with cognitively impaired subjects: unfinished business in the regulation of human research. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:105–111, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Office for Protection From Research Risks, Division of Human Subject Protections: Evaluation of Human Subject Protections in Schizophrenia Research Conducted by the University of California Los Angeles. Los Angeles, University of California, 1994Google Scholar

6. TD v NY State Office of Mental Health, 650 NYS 2d 173 (NY App Div 1996)Google Scholar

7. Berg JW: Legal and ethical complexities of consent with cognitively impaired research subjects: proposed guidelines. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Medical Ethics 24:18–35, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS: The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study: III. abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law and Human Behavior 19:149–174, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C: The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients' capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatric Services 48:1415–1419, 1997Link, Google Scholar

10. Moser DJ, Schultz SK, Arndt S, et al: Capacity to provide informed consent for participation in schizophrenia and HIV research. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1201–1207, 2002Link, Google Scholar

11. Carpenter WT Jr, Gold JM, Lahti AC, et al: Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:533–538, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, et al: Informed consent: assessment of comprehension. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1508–1511, 1998Link, Google Scholar

13. Dunn LB, Lindamer LA, Palmer BW, et al: Improving understanding of research consent in middle-aged and elderly patients with psychotic disorders. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 10:142–150, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Palmer BW, Nayak GV, Dunn LB, et al: Treatment-related decision-making capacity in middle-aged and older patients with psychosis. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 10:207–211, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Roberts LW, Warner TD, Brody JL, et al: Patient and psychiatrist ratings of hypothetical schizophrenia research protocols: assessment of harm potential and factors influencing participation decisions. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:573–584, 2002Link, Google Scholar

16. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR). Sarasota, Fla, Professional Resource Press, 2001Google Scholar

17. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Frank E, et al: Competence of depressed patients for consent to research. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1380–1384, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Kim SYH, Caine ED, Currier GW, et al: Assessing the competence of persons with Alzheimer's disease in providing informed consent for participation in research. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:712–717, 2001Link, Google Scholar

19. Marcus SC, Robins LN, Bucholz KK, et al: Diagnostic Interview Schedule Screening Instrument (DISSI). St Louis, Mo, department of psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, 1989Google Scholar

20. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS: The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T). Sarasota, Fla, Professional Resource Press, 1998Google Scholar

21. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study: I. mental illness and competence to consent to treatment. Law and Human Behavior 19:105–126, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Mulvey E, et al: The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study: II. measures of abilities related to competence to consent to treatment. Law and Human Behavior 19:127–148, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Appelbaum PS, Roth LH: Competency to consent to research: a psychiatric overview. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:951–958, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Berg JW, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: Constructing competence: formulating standards for legal competence to make medical decisions. Rutgers Law Review 48:345–396, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hoge SK, Bonnie RJ, Poythress N, et al: The MacArthur Adjudicative Competence Study: development and validation of a research instrument. Law and Human Behavior 21:141–179, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Overall J, Gorham D: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Hoge SK, Poythress N, Bonnie R, et al: The MacArthur Adjunctive Competence Study: diagnosis, psychopathology, and adjudicative competence-related abilities. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 15:329–345, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Weschler D: The Measurement and Appraisal of Adult Intelligence. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1955Google Scholar

29. Hollingshead A, Redlich F: Social Class and Mental Illness. New York, Wiley, 1958Google Scholar

30. Carpenter WT, Schooler NR, Kane JM: Therationale and ethics of medication-free research in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:401–407, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Pinals DA, Malhotra AK, Breier A, et al: Informed consent in schizophrenia research. Psychiatric Services 49:244, 1998Link, Google Scholar