Violent Victimization of Persons With Co-occurring Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the frequency with which persons in the community with psychiatric disorders, substance use disorders, and both types of disorders are victims of violence. METHODS: The relationship between diagnosis, gender, and victimization over a one-year period was examined in two cross-sectional data sets, one drawn from a study of adaptation to community life of persons with severe mental illness in Connecticut (N=109) and the other drawn from assessments made by caseworkers in a Connecticut outreach project for persons with psychiatric and substance use disorders (N=197). Analysis of variance was used to evaluate the frequency of victimization across diagnostic categories in each data set. RESULTS: People with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders had significantly more episodes of victimization than those with either a psychiatric or a substance use disorder only. Gender was not associated with vicitimization. Qualitative data from focus groups indicated that social isolation and cognitive deficits leading to poor judgment about whom to trust may leave people with serious mental illness vulnerable to drug dealers. CONCLUSIONS: Social environmental mechanisms, such as exploitation by drug dealers, may play an important role in maintaining victimization among persons with co-occurring disorders.

Previous studies have suggested that persons with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders are more frequently violent than persons in the general population who do not have a psychiatric or substance use diagnosis and compared with persons who have severe mental illness only (1,2). Such findings have been highlighted in the popular press (3). However, less attention has been paid to victimization of persons with co-occurring disorders. In this article we present data suggesting that persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders are more likely to be victims of violence compared with persons with either a psychiatric or a substance use disorder only.

Co-occurring disorders may represent a particular risk factor for victimization (4,5). Guy (6) reviewed the records of 2,322 persons receiving aid from a large public agency and asked informants from this group to complete questionnaires inquiring about victimization during the six months preceding data collection. The participants reported receiving threats and experiencing property loss, physical assault, or both. Informants with co-occurring disorders reported significantly more victimization than those with a substance use disorder alone.

Homelessness has been positively associated with victimization among persons with severe mental illness (4,5), and persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders have been reported to have a high risk of homelessness (7,8,9). For example, Drake and colleagues (10) found that approximately one-quarter of a sample of 187 adults with severe mental illness who were admitted to an urban state hospital had unstable housing during the six months before admission, and more than one-half of the subset of adults with co-occurring disorders had unstable housing during that period.

On the basis of such findings, we hypothesized that persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders would experience more victimization than those with a psychiatric or a substance use disorder alone. We used two cross-sectional data sets to explore the relationship between co-occurring disorders and victimization. The first data set was drawn from a 1996 study of adaptation to community life among persons with severe mental illness in Connecticut (11). The second data set was collected by clinicians in an outreach project for persons with psychiatric and substance use disorders conducted in Connecticut in 2002 (12). This data set included information about clients' diagnoses, housing status, and experience of victimization. In addition, we conducted preliminary focus groups with outreach project clinicians to enhance our understanding of social mechanisms from which victimization arises.

Methods

Data sources

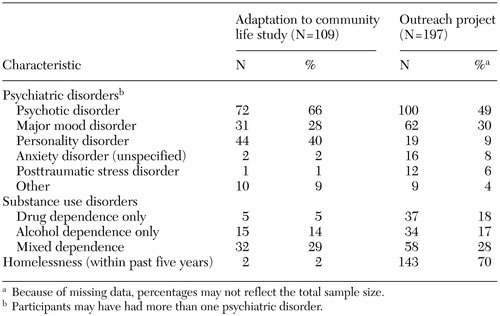

Adaptation to community life study. Forty-six men and 63 women participated in the 1996 adaptation to community life study. The participants ranged in age from 20 to 64 years, with a mean±SD age of 40±10 years. Sixty-nine participants were white, 33 were African American, three were Hispanic, two were Native American, and one was biracial. All participants had a diagnosis of severe mental illness, and about half of the participants had a co-occurring substance use disorder. The participants' diagnoses and data on homelessness are summarized in Table 1.

The human investigations committee of the sponsoring institution for this research approved the study before data collection. The participants were randomly recruited from outpatient services throughout Connecticut. Clinicians referred interested clients to the research staff, who described the study and obtained the participants' written consent. The participants completed interviews assessing psychiatric symptoms, community adjustment, and functioning.

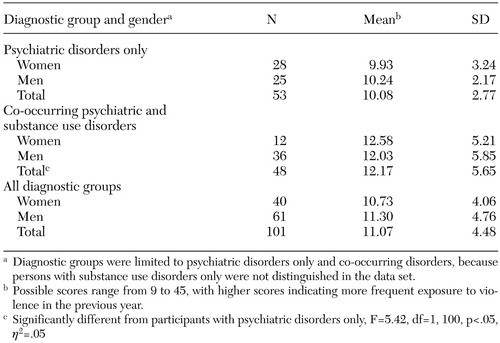

The participants' clinicians provided diagnoses according to the criteria of the DSM-IV. To measure victimization, we used items from the modified Exposure to Community Violence instrument employed in the larger adaptation to community life study (13). The Modified Exposure to Community Violence instrument is a 34-item self-report questionnaire gauging exposure to violence in the community within the previous year along a scale ranging from 1, never, to 5, many times. We used a subset of items that assessed direct exposure to violent behavior, and we added the scores for those items to create an overall estimate of the frequency of victimization. Specifically, the items inquired about being chased by others, threatened with violence, physically assaulted, mugged, sexually assaulted, attacked or stabbed with a knife, shot at or shot with a gun, seriously wounded in a violent incident, and having experienced a home break-in while at home. The range of possible scores was 9 to 45, with higher scores indicating more frequent exposure to violence. These items demonstrated good internal consistency (alpha=.83).

Outreach project. We were granted permission from the outreach project to analyze the data set from an assessment of the program's services, excluding personal information that would identify the participants. The human investigations committee at the institution sponsoring this research exempted this part of the investigation from the requirement for written consent. The outreach clinicians had completed questionnaires from 106 men and 91 women, ranging in age from 19 to 76 years, with a mean age of 43±11 years. A total of 111 clients were African American, 70 were white, 13 were Hispanic, two were of other racial backgrounds, and one was of unknown racial background. The broad diagnostic breakdown was 120 participants with co-occurring disorders, 51 participants with a major psychiatric disorder only, and 26 participants with a substance use disorder only. The participants' diagnoses and data on homelessness are summarized in Table 1.

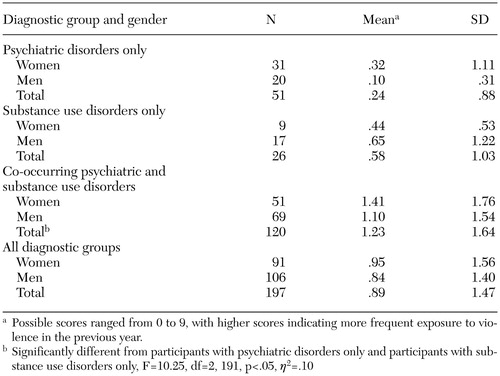

The outreach clinicians provided the participants' diagnoses according to DSM-IV criteria. The clinicians also completed brief scales measuring the participants' experience of victimization over the previous year. The types of victimization included in the scales were being beaten, stabbed, shot at or shot with a gun, sexually assaulted, mugged, chased, threatened with violence, and robbed and having experienced a break-in while at home. We obtained the number of different types of violence experienced to create an overall victimization index. The items were roughly equivalent to those included in the Exposure to Community Violence instrument, showed good face validity, and had adequate internal consistency (alpha=.72). Possible scores ranged from 0 to 9, with higher scores indicating more frequent exposure to violence.

Analysis

We classified participants according to diagnosis and gender, because rates of certain types of victimization vary according to the gender of the victim (4,14,15).

For the data set from the adaptation to community life study, two-by-two factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the frequency of victimization across diagnostic groups and gender. The two diagnostic groups in this analysis were participants with a psychiatric disorder only and participants with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Persons with a substance use disorder only were not distinguished in the data set. The eta-squared (η2) statistic was used to estimate effect size.

For the data set from the outreach project, three-by-two factorial ANOVA with a priori linear contrasts was used to evaluate the frequency of victimization across diagnostic groups and gender. The three diagnostic groups in this analysis were participants with a psychiatric disorder only, participants with a substance use disorder only, and participants with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. The η2 statistic was used to estimate effect size.

Results

As Table 2 shows, participants in the adaptation to community life study who had co-occurring disorders experienced significantly more victimization than those with severe mental illness alone. The results of all other comparisons were nonsignificant.

As Table 3 shows, participants in the outreach project with co-occurring disorders experienced significantly more episodes of victimization than those with a psychiatric disorder only and those with a substance use disorder only. Gender did not affect the results. Between-group contrasts by means of t tests were used to identify specific differences among diagnostic groups, and squared point-biserial correlations (rpb2) were used to estimate the effect size of the contrasts. The results indicated that participants with co-occurring disorders were victimized significantly more often than participants with a psychiatric disorder only (t=4.24, df=194, p<.05, rpb2=.08), a substance use disorder only (t=2.15, df=194, p<.05, rpb2=.02), and either a psychiatric disorder only or a substance use disorder only (t=3.88, df=194, p<.05, rpb2=.07).

To address the potentially confounding factor of homelessness, we analyzed the data from the outreach project by using analysis of covariance to examine the frequency of victimization across diagnosis and gender, with the duration of homelessness in the previous three to five years as a covariate. The results were equivalent to those of the original analysis, although the effect size was slightly diminished (F=7.34, df=2, 190, p<.05, η2=.07).

Contrary to expectations, gender appeared to be unrelated to victimization across the data sets. To explore gender differences in the responses to the various items measuring the experience of specific types of victimization, we conducted independent-sample t tests with data for each item in both data sets. No significant differences were found for any item in the adaptation to community life data set, possibly because of the limited sample size. However, among participants in the outreach project, women were more likely than men to be sexually assaulted (t=2.60, df=118, p<.05, rpb2=.05), and men were more likely than women to be chased by gangs or individuals (t=2.28, df=111, p<.05, rpb2=.04). These results were similar to those of other investigators who have examined differences in rates of victimization between men and women (4).

To better understand the social and contextual dynamics underlying our findings, we conducted preliminary focus groups with staff of the outreach project. Ten female and four male outreach clinicians (mean age=40±7 years) participated in one of two one-hour meetings. Six participants were African American, six were white, and two were Hispanic. They had worked in outreach for a mean of 5±2 years. To begin the meetings, we presented our findings and asked the participants why persons with co-occurring disorders would be victimized more often than others.

Two major themes emerged. First, the outreach staff explained that cognitive obstacles and social isolation related to disorders such as schizophrenia may lead persons with co-occurring disorders to make poor judgments about whom to trust. Consequently, drug dealers have an easy time "befriending" persons with co-occurring disorders and getting them to reveal personal details, such as their favorite places, the drugs they use, and when their monthly disability check arrives. Dealers learn quickly where to go, what drugs to offer, and when to approach these persons to make a sale. Outreach staff described instances of dealers harassing persons with co-occurring disorders by following them in a car and offering them drugs as they walked in their neighborhood. If the dealers were refused, they would use threats and violence to force persons with co-occurring disorders to buy drugs.

A second theme concerned factors that maintained homelessness. For example, supported housing programs often require residents to abstain from substance use. Maintaining abstinence is particularly difficult for persons with co-occurring disorders, who may be subject to threats of violence if they do not continue or increase drug consumption. Consequently, homeless persons with co-occurring disorders are often ineligible for supported housing and are left with no recourse but to return to the streets.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study supported our hypothesis that persons with co-occurring disorders are subjected to violent victimization more often than those with a psychiatric or a substance use disorder alone. The larger size of this effect in the outreach project data set was due primarily to the higher rates of homelessness among the outreach participants.

The qualitative data highlighted the importance of investigating social contexts and processes to obtain a fuller understanding of the mechanisms of victimization. Explanations of victimization that emphasize social context contrast with hypotheses such as lifestyle routine activity theory (16), which highlights victims' roles in precipitating their own victimization through certain behaviors. Although not as directly applicable to victimization, some theories concerning self-medication and treatment noncompliance are similar to these hypotheses in that they attribute treatment failure to the client. For example, a client who self-medicates is seen as choosing substance abuse as a way to ameliorate distress, and a client who is noncompliant with treatment is seen as thwarting recovery by disregarding treatment directives. Such ideas may reflect some of the reality behind the often protracted recoveries of persons with co-occurring disorders, but they may also overstate the agency of persons who are in the grips of severe mental illness and addiction.

The preliminary qualitative data from this study suggested that for persons with co-occurring disorders substance abuse is not simply a means of self-medication but is also maintained by others as a channel of financial exploitation. Correspondingly, treatment noncompliance by persons with co-occurring disorders may not reflect limited personal motivation for recovery so much as sabotage by others with vested interests in impeding the recovery.

Our study had several limitations. First, we used data sets derived from studies with cross-sectional designs in which the data were gathered at one point in time. Consequently, we cannot be certain whether substance abuse or dependency preceded or followed victimization. Investigations with longitudinal designs may be more suitable for addressing questions of causality.

Second, our sample sizes were modest (N=109 and N=197), which could have threatened the study's external validity. Future research should include larger samples to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Despite their modest sizes, the samples in our study did appear to be representative of the population of people with severe mental illness considered in other studies (4,5).

Third, our measures of victimization were drawn from participants' self-reports and clinicians' reports, which could distort the data. However, previous research has suggested that self-reports tend to be more accurate than police records of victimization, which have been found to underrepresent the scope of victimization (5).

Our initial efforts at combining quantitative and qualitative data in this investigation may be useful in developing theories about the relationship between co-occurring disorders and victimization. Our efforts were responsive to recent recommendations in the field to better address the underlying processes of victimization (17) rather than simply to identify risk factors. To address the limitations in the study reported here, we are conducting additional focus groups with outreach project staff and are using these data to guide further quantitative data collection. We expect that integration of qualitative and quantitative data will allow a fuller understanding of the contexts and processes underlying victimization and that the findings will potentially inform treatment and public policy decisions concerning persons with co-occurring disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 8-T32-DA15733-13 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors thank Dr. Sybille Guy and Dr. Cory Bridwell for comments on earlier drafts.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Send correspondence to Dr. Sells at Yale Department of Psychiatry, Program for Recovery and Community Health, 205 Whitney Avenue, Suite 306, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of sets of participants in an analysis of the relationship of co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders with violent victimization

|

Table 2. Scores on a measure of violent victimization of participants in the adaptation to community life study, by diagnostic group and gender

|

Table 3. Scores on a measure of violent victimization of participants in the outreach project, by diagnostic group and gender

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393–401, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:226–231, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Butterfield F: Studies of mental illness show links to violence. New York Times, May 15, 1998, p A14Google Scholar

4. Goodman LA, Salyers MP, Mueser KT, et al: Recent victimization in women and men with severe mental illness: prevalence and correlates. Journal of Traumatic Stress 14:615–632, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, et al: Criminal victimization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:62–68, 1999Link, Google Scholar

6. Guy SM: Mental health services and the dually diagnosed patient: assessment of financial and social costs involved in missed diagnosis or treatment. Doctoral dissertation. University of California, Los Angeles, department of psychology, 1997Google Scholar

7. Belcher JR: On becoming homeless: a study of chronically mentally ill persons. Journal of Community Psychology 17:173–185, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Drake RE, Osher FC, Wallach MA: Homelessness and co-occurring disorders. American Psychologist 46:1149–1158, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Drake RE, Wallach MA, Teague GH, et al: Housing instability and homelessness among rural schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:330–336, 1991Link, Google Scholar

10. Drake RE, Wallach MA, Hoffman JS: Housing instability and homelessness among aftercare patients of an urban state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:46–51, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Dailey WF, Chinman MJ, Davidson L, et al: How are we doing? A statewide survey of community adjustment among people with serious mental illness receiving intensive outpatient services. Community Mental Health Journal 36:363–382, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Rowe M, Hoge MA, Fisk D: Services for mentally ill homeless persons: street level integration. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:490–496, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Richters JE: Screening survey of exposure to community violence: self-report version. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1990Google Scholar

14. Marley JA, Buila S: Crimes against people with mental illness: types, perpetrators, and influencing factors. Social Work 46:115–124, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Criminal Victimization in the United States, 1987. Washington DC, US Department of Justice, 1989Google Scholar

16. Hindelang M, Gottfredson M, Garofolo J: Victims of Personal Crime: An Empirical Foundation for a Theory of Personal Victimization. Cambridge, Mass, Ballinger, 1978Google Scholar

17. Sampson RJ, Lauritsen JL: Violent victimization and offending: individual-, situational-, and community-level risk factors, in Understanding and Preventing Violence. Edited by Reiss AJ Jr, Roth JA. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1994Google Scholar