Prevalence, Assessment, and Treatment of Pathological Gambling: A Review

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Although pathological gambling is an increasing problem, many mental health providers are unfamiliar with its diagnosis and treatment. To improve recognition and treatment of pathological gambling, the authors reviewed the literature on its prevalence, assessment, and treatment. METHODS: Entries in PsycLIT and MEDLINE were examined for the years 1984 to 1998. Results and discussion: The prevalence of pathological gambling seems to be increasing with the spread of legalized gambling; casinos are now operating in 27 states. Point and lifetime prevalence rates of pathological gambling are reported to be as high as 1.4 percent and 5.1 percent, respectively. The most commonly used assessment instrument is the DSM-based, 20-item South Oaks Gambling Screen. There is no standard treatment for pathological gambling. Gamblers Anonymous (GA) is the most popular intervention, and about 1,000 chapters exist in the U.S. Studies suggest that only 8 percent of GA attendees achieve a year of abstinence. Combining professional therapy and GA participation may improve retention and abstinence. Marital and family treatments, including participation in Gam-Anon, the spousal component of GA, have not been sufficiently evaluated. The few studies of cognitive-behavioral treatments suggest that this approach, which may include cognitive restructuring, problem solving, social skills training, and relapse prevention, is promising. Carbamazepine, naltrexone, clomipramine, fluvoxamine, and lithium have been used with some effect. Therapists' manuals and self-help manuals are available. Although research evaluating their efficacy is necessary, manuals can provide a start for therapists who encounter patients with gambling problems. Brief motivational interviewing may be a useful strategy for decreasing gambling among heavy gamblers who are ambivalent about entering treatment or who do not desire abstinence.

Although gambling is a form of entertainment for many people, some individuals develop a pattern of gambling characterized by lack of control, "chasing" of losses, lies, and illegal acts (1). Pathological gambling is recognized as a psychological disorder in DSM-IV (2), but relatively little effort has been dedicated to identifying and treating this disorder. For three reasons, clinicians should become familiar with the diagnosis of this condition, and investigation of treatment strategies should be expanded.

One reason that clinicians should become more involved is that pathological gambling results in serious personal and societal problems, including financial, legal, employment, medical, and psychological difficulties. For example, gambling-related debts ranging from $38,000 (3) to $113,000 (4) have been reported in the literature, and up to 60 percent of pathological gamblers commit illegal acts to support gambling (3,4,5). Pathological gambling is also associated with health consequences, including high rates of insomnia, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiac problems, high blood pressure, and headaches (6,7).

Comorbid psychiatric conditions are also common. Up to 50 percent of gamblers have substance use disorders (8,9,10). Obsessive-compulsive disorder (11), attention-deficit disorder (12), anxiety disorders (11,13,14), and depressive disorders (7,13,14) occur frequently in pathological gamblers, and some reports suggest that these conditions share a physiological substrate with pathological gambling (9,15,16,17). Gamblers also are at increased risk for suicide. Between 48 percent and 70 percent of pathological gamblers contemplate suicide (3,4), and 13 to 20 percent attempt suicide (18).

A second reason for devoting attention to pathological gambling is that prevalence seems to be increasing in the United States (19). Most states enacted antigambling legislation during the early 1900s, but in 1964 state lotteries were inaugurated. Recently, states have begun legalizing casino gambling, and casinos are now operating in 27 states.

Along with this spread of legalized gambling, participation in gambling has increased (19,20). Between 1991 and 1995, wagering in the U.S. rose steadily from $300 to more than $500 billion a year (21). Problem gambling behaviors have paralleled the spread of legalized gambling. In a 1974 survey, .7 percent of a national sample was classified as probable compulsive gamblers and another 2.3 percent as problem gamblers (22). More recent data indicate point and lifetime prevalence of pathological gambling to be as high as 1.4 percent (19) and 5.1 percent (20), respectively.

A third reason for expanding efforts toward assessment and treatment of pathological gambling is that public awareness of the problem is growing. Newspapers frequently print articles on compulsive gambling, and widely publicized segments on pathological gambling have been aired on television. In fact, gambling has been characterized as the addiction of the 1990s.

As public awareness of the problem grows, more gamblers are seeking treatment. The first treatment program for gambling was created in Ohio in 1968. Other programs have since been developed, and a certification procedure for treatment pro-viders has been established. Some casinos and state lotteries now fund treatment programs, and some credit card companies and lending institutions have begun training personnel to manage financial problems of pathological gamblers. However, fewer than 150 clinicians are nationally certified gambling counselors, and only 100 programs provide treatment for pathological gamblers. Only 21 of the programs are state supported, and individuals can remain on a waiting list for as long as six months.

Despite increasing awareness of the disorder, most pathological gamblers do not seek or receive treatment. Pathological gambling remains largely undiagnosed and untreated, even among high-risk populations such as substance abusers. Even when gambling affects work performance, employee assistance programs rarely recognize the problem or provide specialized treatment (23). In the remainder of this paper, guidelines for assessment and diagnosis are briefly described, and treatments are reviewed.

Methods

A review of the literature on pathological gambling was conducted using PsycLIT and MEDLINE. The keywords "gambling" and "gamblers" were used, and entries from the years 1984 to 1998 were examined. Articles that evaluated screening instruments or the efficacy of treatment are reviewed in this paper.

Results

Screening and identifying problem gamblers

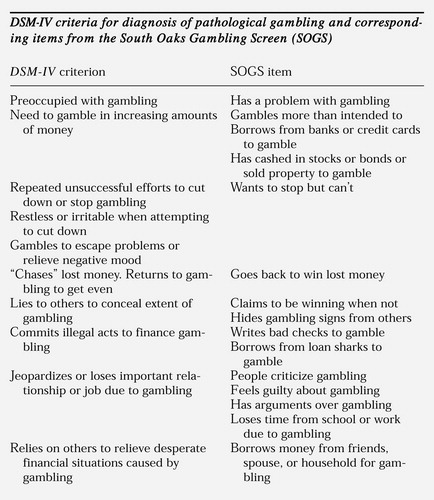

The most common instrument for assessing gambling problems is the 20-item South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) (24). Individuals endorsing five or more items are identified as probable pathological gamblers. The instrument is based on DSMcriteria and demonstrates good reliability and validity in clinical samples (24). It has been used in epidemiological studies, but data about its psychometric properties in general populations are lacking (20). The accompanying box lists DSM-IV criteria and corresponding items from the SOGS.

Despite widespread use of the SOGS, some criticisms have been made. Because it is a lifetime measure, it is not sensitive to changes over time. It also has been criticized as having a high false-positive rate (1,25).

A shorter alternative to the SOGS is the Lie/Bet screen (26). It consists of two questions: Have you ever felt the need to bet more and more money? and, Have you ever had to lie to people important to you about how much you gamble? These questions show sensitivity and specificity in identifying pathological gamblers (26).

Treatments for pathological gambling

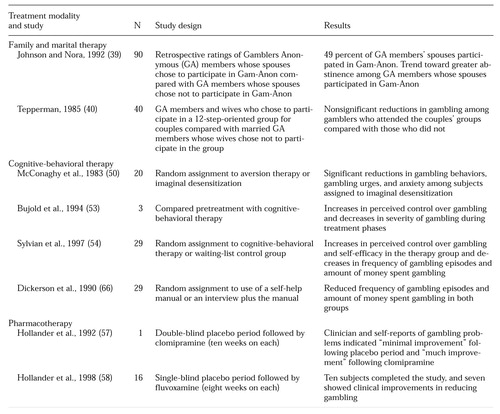

Once pathological gambling is identified, clinicians are left with the responsibility of treating the condition. Only a few studies have compared treatments; they are shown in Table 1. However, different treatment approaches have been described.

Gamblers Anonymous.

Gamblers Anonymous (GA) is the most popular intervention for problem gambling, and about 1,000 chapters exist in the U.S. However, some evidence suggests that GA may not be very effective. Retrospective reports indicate that 70 to 90 percent of GA attendees drop out (27,28) and that less than 10 percent become active members (29). Moreover, only 8 percent of attendees achieve a year or more of abstinence (27). Thus, while GA may help some people achieve and maintain abstinence from gambling, it seems to have beneficial effects for only a minority of participants.

Professional treatment plus GA.

Combining professional therapy and GA may improve retention and abstinence compared with GA participation alone. Lesieur and Blume (16) studied outcomes of patients treated for gambling in a combined alcohol, drug, and gambling program. Patients received multimodal individual and group therapy, and GA attendance was strongly encouraged. Of 124 patients admitted with gambling problems, 72 were interviewed between six and 14 months after discharge. Gambling problems decreased significantly compared with pretreatment levels, and 64 percent of patients achieved abstinence.

Blackman and associates (30) described outcomes of 88 gamblers entering a treatment clinic; significant reductions in frequency of gambling and indebtedness were noted. Russo and colleagues (31) contacted 60 of 124 patients who completed a program for veterans combining individual psychotherapy, group therapy, and GA attendance. Abstinence was reported by 55 percent. Taber and colleagues (32) conducted a six-month follow-up of 57 of 66 patients consecutively admitted to the same Veterans Administration facility. Total abstinence was reported by 56 percent, and decreases in psychological symptoms, employment problems, and substance use were noted.

Although these reports suggest that pathological gambling is a treatable disorder, they suffer from methodological flaws. One problem is that the reports do not specifically describe the therapy, so replication is not possible. In addition, most pathological gamblers are not likely to receive services from clinicians experienced with the disorder, so generalization of findings from specialized treatment clinics may not be appropriate. It is also unclear whether patients would have improved without such intensive treatment. Despite these problems, the reports suggest that professionally delivered therapy in combination with GA participation may improve outcomes compared with GA participation alone.

Psychodynamic treatments.

Ro-senthal (33) describes psychodynamic treatment for gamblers, which focuses on low ego strength and narcissism as well as on grief associated with giving up gambling (34). In 1957 Bergler (35) reported on psychodynamic treatment of 60 gamblers. He claimed a success rate of 75 percent, but this figure is based on only 30 percent of the original sample—presumably those who remained in treatment.

Marital and family treatments.

Clinicians have noted that family structures of gamblers are chaotic and turbulent, and couples' treatment has been described. Because debts of gamblers are large, Heineman (36) suggested dealing with finances during therapy. Steinberg (37) described reframing the potentially negative experience of turning finances over to the nongambling spouse. Boyd and Bolen (38) provided treatment focusing on identifying feelings of the partner and understanding gambling within the context of the relationship. Nine gamblers and their wives participated; three achieved abstinence, and most reduced gambling.

GA has a spousal component, known as Gam-Anon. Johnson and Nora (39) found that GA members whose spouses participated in Gam-Anon were more likely to achieve abstinence than those whose spouses did not. However, the difference was not statistically significant, and participation was self-selected. Tepperman (40) compared GA members who participated with their wives in a 12-step couples group and married GA members who chose not to receive couples' treatment. Only half of each sample remained in treatment. Although reductions in depression and marital discord occurred, no differences in gambling or psychosocial problems were noted between groups. Again, participation in the interventions was self-selected, further obscuring interpretation of the results.

Zion and colleagues (41) concluded that little evidence suggests that spousal involvement in Gam-Anon reduces relapse, although some family members may find it useful. More research is needed to more clearly define and evaluate family therapy for gamblers.

Cognitive-behavioral therapies.

The task force on promotion and dissemination of psychological procedures of the American Psychological Association rated cognitive and behavioral therapies that have been empirically validated as treatments for depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (42). Some reports suggest that these therapies are effective in treating other disorders that overlap with gambling, including substance use disorders (43).

Early behavioral therapies involved delivering shocks to subjects as they gambled or were exposed to gambling stimuli (44,45). Blaszczynski and associates reviewed these approaches (46). Other articles (46,47,48,49) suggest incorporating cognitive techniques, but efficacy data are lacking.

In one of the few controlled studies directly comparing two treatments, Australian researchers randomly assigned 20 gamblers to one of two therapies: aversion therapy or imaginal desensitization (50). Subjects receiving imaginal desensitization reported significantly less gambling and fewer urges to gamble at one month (50) and up to nine years after treatment (51,52). Although this study is superior to most because of its use of random assignment and clearly defined treatments, imaginal desensitization has been tested only on an intensive inpatient basis (14 sessions a week), and its efficacy has not been tested in typical outpatient settings.

Bujold and colleagues (53) successfully used cognitive restructuring, problem solving, social skills training, and relapse prevention in weekly individual sessions with three gamblers. Sylvian and associates (54) applied a similar treatment in a controlled trial: 29 gamblers were randomly assigned to active treatment or a waiting-list control group. Subjects assigned to active treatment evidenced significant reductions in gambling and reported increased perceived control over gambling compared with control subjects. These findings suggest the efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for pathological gamblers. However, the study failed to provide data from the subjects who did not complete treatment (36 percent), and length of time in treatment and on the waiting list varied among subjects. Although this cognitive-behavioral approach seems promising, further evaluation is necessary.

Pharmacotherapies.

Several case reports suggest pharmacotherapies may be useful in treating gamblers. Haller and Hinterhuber (55) described the use of the anticonvulsant carbamazepine. In another case report, Kim (56) showed beneficial effects of the opioid antagonist naltrexone, which is hypothesized to reduce the high associated with gambling. Others have tried drugs affecting the serotonin neurotransmitter system. In a study in which subjects received placebo for a period before clo-mipramine was started, clomipra-mine was found more effective than placebo in treating a pathological gambler with obsessive-compulsive personality features (57). A single-blind study of fluvoxamine demonstrated reductions in gambling in seven of ten gamblers (58).

Moskowitz (59) treated three gamblers with lithium and observed that the drug seemed to blunt the excitement associated with gambling. Although manic episodes are an exclusion criterion for a diagnosis of pathological gambling, gambling problems occur frequently in patients with bipolar disorder and in families of bipolar probands (60). Further research should evaluate gambling behaviors during the course and treatment of bipolar disorder.

Given the high rates of comorbidity between pathological gambling and depression (7,13,14), more research is also needed on the efficacy of antidepressants in treating depressed pathological gamblers. Some evidence suggests that depressed moods may precipitate or prolong gambling episodes (61). Pharmacological treatment for depression may reduce the association between negative mood states and gambling.

In summary, several reports suggest that pharmacotherapies may be useful in treating pathological gambling. However, all these studies suffer from small and select samples, and only two included a placebo control. No consensus has been reached on which drugs may be most useful or on the type of psychotherapy, if any, that should be provided concurrently. Future research should evaluate the efficacy of pharmacotherapies, especially in the treatment of dually diagnosed gamblers.

Other treatment issues

Manual-guided therapies.

The use of manual-guided therapies has been considered one of the most important developments in psychotherapy. The objective is to clearly specify therapies, provide guidelines for their implementation, and establish clear standards of care (62). Available data suggest that standardized treatment is superior to reliance on individual clinical judgment (63). The development of manualized treatments may be especially important in treating pathological gamblers because so few providers of specialized treatment are available.

Sylvian and colleagues (54) developed a treatment manual for pathological gambling that incorporates cognitive restructuring, problem solving, social skills training, and relapse prevention. The efficacy of this manual has been demonstrated in one clinical treatment trial. However, replication in other sites is needed.

We have developed a manual for an eight-session treatment that tailors many of the exercises from cognitive-behavioral treatments of substance use disorders to the needs of gamblers, and we are testing its efficacy in a controlled study.

Intensity of treatment.

Another important issue is the intensity of interventions. Minimal treatments have been developed in response to the effort to reduce health service costs and the growing evidence that some intensive traditional treatments are no more effective than briefer interventions (64,65). Minimal interventions range from motivational interviewing to brief advice or the use of self-help manuals.

Some evidence suggests that self-help manuals may be effective in treating pathological gambling. In Australia, Dickerson and associates (66) found that use of a self-help manual significantly reduced gambling, alone or in conjunction with a single in-depth motivational interview. Although the study did not evaluate a control condition and failed to assess compliance with the manual, results suggest that a self-help manual may be useful in treating gamblers.

Blaszczynski (67) recently published a self-help manual, and we are comparing professionally delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy to the same treatment content delivered through a self-help manual. Such manuals may be a low-cost and practical alternative to individual therapy, especially among those without the resources or insurance to pay for treatment. Recommendation of a self-help manual may be a cost-effective initial step in addressing problem gambling. Clients who do not seem to benefit from this approach may then be referred for more intensive treatment.

Treatment strategies.

Research suggests that abstinence may not be the most appropriate goal for all individuals with alcohol use disorders and that reduction in use may be an appropriate strategy for a subset of individuals (68). Some data suggest that reductions in gambling may also be a viable goal for pathological gamblers (51,69,70). The self-help manuals by Dickerson and colleagues (66) and Blaszczynski (67) emphasize skills for reducing gambling. Brief motivational interviewing may be a useful strategy for decreasing gambling among heavy gamblers who are ambivalent about entering treatment or who do not desire abstinence.

Discussion and conclusions

Pathological gambling is a growing problem, with financial, employment, legal, psychological, familial, and public health consequences. Nevertheless, no standard treatment currently exists. With the exception of the studies by McConaghy and colleagues (50) and Sylvian and colleagues (54), most of the reports reviewed in this paper did not compare the efficacy of different psychotherapies or pharmacotherapies or failed to randomly assign subjects. Most did not clearly define the therapy, and the majority of reports included fewer than 30 subjects, with most reporting only single cases. Despite these shortcomings, studies of cognitive-behavioral treatments (48,49,50,5454), including two controlled trials (50,54), suggest that these treatments may be useful in decreasing gambling.

Therapists' manuals and self-help manuals (54,66,67) are available for treating pathological gamblers. Although further research on their efficacy is necessary, these manuals can provide a start for therapists who encounter patients with gambling problems. In addition, referral to GA and Gam-Anon may assist some gamblers and their families, although GA participation alone may not be sufficient. Medications may be useful for pathological gamblers, especially those with concurrent psychiatric diagnoses. As public awareness of pathological gambling and its consequences grows, funds may become available to better evaluate these treatment approaches in controlled studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ron Kadden, Ph.D., Henry Kranzler, M.D., and Lance Bauer, Ph.D., for helpful comments. This work was supported by grant R29-DA-12056 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and grant P50-AA-03510 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and a grant from the research initiation support enhancement program at the University of Connecticut Health Center.

Dr. Petry is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, 263 Farmington Avenue, Farmington, Connecticut 06030-2103 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Armentano is with the compulsive gambling treatment program of the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services in Middletown, Connecticut.

Figure. DSM-IV criteria for diagnosis of pathological gambling and corresponding items from the South oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS)

|

Table 1. Studies that compared the efficacy of two treatments for pathological gambling

1. Lesieur HR: The Chase: Career of the Compulsive Gambler. Cambridge, Mass, Schenkman, 1984Google Scholar

2. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

3. Thompson WN, Gazel R, Rickman D: The social costs of gambling in Wisconsin. Wisconsin Policy Research Institute Report 9(6):1-44, 1996Google Scholar

4. Lesieur HR, Anderson C: Results of a Survey of Gamblers Anonymous Members in Illinois. Park Ridge, Ill, Illinois Council on Problem and Compulsive Gambling, 1995Google Scholar

5. Rosenthal RJ, Lorenz VC: The pathological gambler as criminal offender. Clinical Forensic Psychiatry 15:647-660, 1992Google Scholar

6. Lorenz VC, Yaffee RA: Pathological gambling: psychosomatic, emotional, and marital difficulties as reported by the gambler. Journal of Gambling Behavior 2:40-49, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Bergh C, Kuhlhorn E: Social, psychological, and physical consequences of pathological gambling in Sweden. Journal of Gambling Studies 10:275-285, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Cunningham-Williams RM, Cottler LB, Compton WM, et al: Taking chances: problem gamblers and mental health disorders: results from the St Louis Epidemiological Catchment Area study. American Journal of Public Health 88:1093-1096, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lesieur HR, Blume SB, Zoppa RM: Alcoholism, drug abuse, and gambling. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 10:33-38, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Ramirez LF, McCormick RA, Russo AM, et al: Patterns of substance abuse in pathological gamblers undergoing treatment. Addictive Behavior 8:425-428, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Linden RD, Pope HG, Jones JM: Pathological gambling and major affective disorder: preliminary findings. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 47:201-203, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

12. Carlton PL, Manowitz P, McBride H, et al: Attention deficit disorder and pathological gambling. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 48:487-488, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

13. Blaszczynski AP, McConaghy N: Anxiety and/or depression in the pathogenesis of pathological gambling. International Journal of the Addictions 24:337-350, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. McCormick RA, Russo AM, Ramirez LF, et al: Affective disorders among pathological gamblers seeking treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:215-218, 1984Link, Google Scholar

15. Comings DE, Rosenthal RJ, Lesieur HR, et al: A study of the dopamine D2 receptor gene in pathological gambling. Pharmacogenetics 6:223-234, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Lesieur HR, Blume SB: Evaluation of patients treated for pathological gambling in a combined alcohol, substance abuse, and pathological gambling treatment unit using the Addiction Severity Index. British Journal of Addiction 86:1017-1028, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Roy A, Adinoff B, Roehrich L, et al: Pathological gambling: a psychobiological study. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:369-373, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Frank ML, Lester D, Wexler A: Suicidal behavior among members of Gamblers Anonymous. Journal of Gambling Studies 7:249-254, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Volberg RA: The prevalence and demographics of pathological gamblers: implications for public health. American Journal of Public Health 84:237-241, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Volberg RA: Prevalence studies of problem gambling in the United States. Journal of Gambling Studies 12:111-128, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. The Impact of Casinos and Gaming Devices on the New York Racing Association. New York, Christiansen/Cummings Associates, 1996Google Scholar

22. Kallick M, Suits D, Dielman T, et al: A Survey of Gambling Attitudes and Behavior. Ann Arbor, Mich, Institute for Social Research, 1979Google Scholar

23. Lesieur HR: Experience of employee assistance programs with pathological gamblers. Journal of Drug Issues 19:425-436, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Lesieur HR, Blume SB: The South Oaks Gambling Screen (the SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1184-1188, 1987Link, Google Scholar

25. Culleton RP: The prevalence rates of pathological gambling: a look at methods. Journal of Gambling Studies 5:22-41, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Johnson EE, Hamer R, Nora RM, et al: The Lie/Bet questionnaire for screening pathological gamblers. Psychological Reports 80:83-88, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Brown RIF: The effectiveness of Gamblers Anonymous. Gambling Studies: Proceedings of the Sixth National Conference on Gambling and Risk Taking: Vol 5: The Phenomenon of Pathological Gambling. Edited by Eadington WR. Reno, University of Nevada, Bureau of Business and Economic Administration, 1985Google Scholar

28. Lester D: The treatment of compulsive gambling. International Journal of the Addictions 15:201-206, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Stewart RM, Brown RIF: An outcome study of Gamblers Anonymous. British Journal of Psychiatry 152:284-288, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Blackman S, Simone RV, Thoms DR, et al: The Gamblers Treatment Clinic of St Vincent's North Richmond Community Mental Health Center: characteristics of the clients and outcome of treatment. International Journal of the Addictions 24:29-37, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Russo AM, Taber JI, McCormick RA, et al: An outcome study of an inpatient treatment program for pathological gamblers. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:823-827, 1984Abstract, Google Scholar

32. Taber JI, McCormick RA, Ramirez LF: The prevalence and impact of major life stressors among pathological gamblers. International Journal of the Addictions 22:71-79, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Rosenthal RJ: The pathological gambler's system for self-deception. Journal of Gambling Behavior 2:108-120, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Miller W: Individual outpatient treatment of pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling of Behavior 2:95-107, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

35. Bergler E: The Psychology of the Gambler. New York, International University Press, 1957Google Scholar

36. Heineman M: Recovery for Compulsive Gamblers and Their Families: Losing Your Shirt. Minneapolis, CompCare Publishers, 1992Google Scholar

37. Steinberg MA: Couples treatment issues for recovering male compulsive gamblers and their partners. Journal of Gambling Studies 9:153-167, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Boyd W, Bolen DW: The compulsive gambler and spouse in group psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 20:77-90, 1970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Johnson EE, Nora RM: Does spousal participation in Gamblers Anonymous benefit compulsive gamblers? Psychological Reports 71:914, 1992Google Scholar

40. Tepperman JH: The effectiveness of short-term group therapy upon the pathological gambler and wife. Journal of Gambling Behavior 1:119-130, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Zion MZ, Tracy E, Abell N: Examining the relationship between spousal involvement in Gam-Anon and relapse behaviors in pathological gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies 7:117-131, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Treatments of Psychological Disorders: A Report to the Division 12 Board. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1993Google Scholar

43. Marlatt GA, Gordon JR (eds): Relapse Prevention. New York, Guilford, 1985Google Scholar

44. Barker JC, Miller M: Aversion therapy for compulsive gambling. Lancet 1:491-492, 1966Crossref, Google Scholar

45. Koller KN: Treatment of poker machine addicts by aversion therapy. Medical Journal of Australia 1:742-745, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Blaszczynski AP, Silove D: Cognitive and behavioral therapies for pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies 11:195-220, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Murray JB: Review of research on pathological gambling. Psychological Reports 72:791-810, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Toneatto T, Sobell LC: Pathological gambling treated with cognitive behavior therapy: a case report. Addictive Behaviors 15:497-501, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Sharpe L, Terrier N: Towards a cognitive-behavioural theory of problem gambling. British Journal of Psychiatry 162:407-412, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. McConaghy N, Armstrong MS, Blaszczynski A, et al: Controlled comparison of aversive therapy and imaginal desensitization in compulsive gambling. British Journal of Psychiatry 142:366-372, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Blaszczynski AP, McConaghy N, Frankova A: Control versus abstinence in the treatment of pathological gambling: a two- to nine-year follow-up. British Journal of Addiction 86:299-306, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. McConaghy N, Blaszczynski A, Frankova A: Comparisons of imaginal desensitization with other behavioral treatments of pathological gambling: a two- to nine-year follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 159:390-393, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Bujold A, Ladouceur R, Sylvain C, et al: Treatment of pathological gamblers: an experimental study. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 25:275-282, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Sylvian C, Ladouceur R, Boisvert JM: Cognitive and behavioral treatment of pathological gambling: a controlled study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:727-732, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Haller R, Hinterhuber H: Treatment of pathological gambling with carbamazepine. Pharmacopsychiatry 27:129, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Kim SW: Opioid antagonists in the treatment of impulse-control disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59:159-164, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Hollander E, Frenkel M, DeCaria C, et al: Treatment of pathological gambling with clomipramine [ltr]. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:710-711, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

58. Hollander E, DeCaria C, Mari E, et al: Short-term single-blind fluvoxamine treatment of pathological gambling. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1781-1783, 1998Link, Google Scholar

59. Moskowitz JA: Lithium and lady luck: use of lithium carbonate in compulsive gambling. New York State Journal of Medicine 80:785-788, 1980Medline, Google Scholar

60. Winokur G, Clayton PJ, Reich T: Manic Depressive Illness. St Louis, Mosby, 1969Google Scholar

61. Dickerson MG, Cunningham R, England SL, et al: On the determinants of persistent gambling: III. personality, prior mood, and poker machine play. International Journal of the Addictions 26:531-548, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Rounsaville BJ, O'Malley S, Foley S, et al: Role of manual-guided training in the conduct and efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 56:681-688, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Wilson GT: Manual-based treatments: the clinical application of research findings. Behavioral Research and Therapy 34:295-314, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Babor TF: Avoiding the horrid and beastly sin of drunkenness: does dissuasion make a difference? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:1127-1140, 1994Google Scholar

65. Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS: Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction 88:315-336, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Dickerson MG, Hinchy J, England S: Minimal treatments and problem gamblers: a preliminary investigation. Journal of Gambling Studies 6:87-102, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Blaszczynski A: Overcoming Compulsive Gambling: A Self-Help Guide Using Cognitive-Behavioral Techniques. London, Robinson, 1998Google Scholar

68. Sobell MB, Sobell LC: Individualized behavior therapy for alcoholics. Behavior Therapy 4:49-72, 1973Crossref, Google Scholar

69. Dickerson MG, Weeks D: Controlled gambling as a therapeutic technique for compulsive gamblers. Journal of Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 10:139-141, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

70. Rankin H: Control rather than abstinence as a goal in the treatment of excessive gambling. Behavioral Research and Therapy 20:185-187, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar