Setting Benchmarks and Determining Psychiatric Workloads in Community Mental Health Programs

Abstract

Administrators and clinicians must find ways to effectively and efficiently use psychiatric resources without compromising the quality of care. The author outlines a model for setting benchmarks for allocating psychiatrists' time in a community mental health service setting. After the percentage of time for direct-care activities is agreed on (for example, 60 percent), the amounts of time necessary for three direct-care clinical activities—assessment of new patients, follow-up of stable patients, and follow-up of unstable patients and emergencies—are established. Time for documentation should be included in each task. At the end of six months, workloads are evaluated, and benchmarks are reset as appropriate.

Typically, psychiatric resource needs are expressed as the ratio of the number of full-time-equivalent psychiatrists per 100,000 population. Unfortunately, this measure is very crude and does not take into account the complexities of psychiatric illness, variations in psychiatric morbidity, needs of individual patients, the availability of mental health professionals other than psychiatrists, and the changing roles and responsibilities of psychiatrists.

This crude ratio is meaningless when we attempt to allocate psychiatric resources within a hospital to various programs or when we try to determine appropriate psychiatric workloads for effective and efficient patient care. Thus there is an urgent need to set more specific guidelines and provisional benchmarks to ensure effective resource allocation. Furthermore, without guidelines or benchmarks we run a serious risk of a decline in service standards, which generally leads to increased liability, client dissatisfaction, staff demoralization, and burnout.

Articles published in recent years have looked at psychiatric manpower requirements and staffing needs (1,2), roles of psychiatrists in mental health centers (3), disparity between workloads and resources and physician liability (4), and job satisfaction (5). However, few reports aim to set guidelines or benchmarks for psychiatric workloads and for time spent by psychiatrists in various clinical activities.

This paper describes a method to establish provisional guidelines and benchmarks for direct-care psychiatric services in a public-sector community mental health setting. Indirect services were not addressed.

Methods

Definitions

For the model, a full-time-equivalent (FTE) psychiatrist was defined as one who is contracted for 37.5 hours a week (or for ten 3.75-hour sessions) and for 45 weeks a year. (In Canada a session is 3.75 hours, with two sessions per day and ten per week. Psychiatrists may work part time for fewer sessions, such as four or eight, per week.) Psychiatrists perform different tasks, which can be categorized broadly into direct-care and indirect-care activities.

Direct-care activities were defined as all interactions with the patient that are significant and need documentation. Indirect-care activities were defined as all activities conducted on behalf of the patient to ensure that appropriate care is provided. These activities include triage, team rounds, liaison with other clinicians and community agencies, consultation, family meetings, and so forth. Also included but often neglected under this category are teaching, administration, and research activities, which need special attention.

A caseload was defined as the total number of active clients on a psychiatrist's list at any given point. Caseload defined in this way is not a true reflection of the work a psychiatrist performs each week; for instance, some patients in the caseload may be stable, and the psychiatrist may see them only once every three months, with interim follow-up by a nurse. A more accurate measure is provided by examining the workload of each psychiatrist.

Workload was defined as the actual work done by a psychiatrist, which includes direct-care activities (number of cases seen each week) as well as other indirect-care activities.

Study procedure

A number of approaches to estimating psychiatric manpower requirements have been described (1), each with its advantages and disadvantages. We adopted an approach similar to that described by Goldman and colleagues (2), with slight modifications. In their article they suggested "minimum" and "desired" amounts of time needed to see certain groups of patients. For stable patients, the minimum they suggested is three minutes a week, and the desired time is five minutes a week. In their model, unstable patients require 15 minutes minimum, with a desired time of 20 minutes. For each new assessment or emergency, 45 minutes a week is the minimum time, and 60 minutes the desired time.

We felt that the approach used by Goldman and colleagues could not provide acceptable standards of patient care. We also felt that it may lead to clinical oversight and negligence and thus present liability risks for physicians. Under this approach to care, client satisfaction would drop significantly and job satisfaction for psychiatrists would plummet, with resultant stress and burnout. Diamond and associates (3) described "essential" and "desirable" roles for psychiatrists, which helped focus our attention on the changing role of psychiatrists in mental health centers and the need to allocate time to provide essential indirect care services.

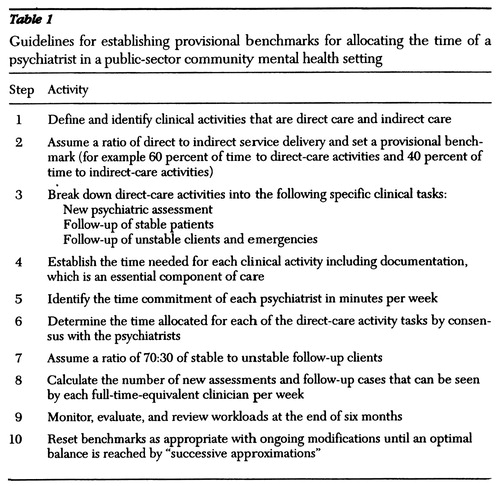

Table 1 presents the guidelines we suggest for establishing provisional benchmarks for different psychiatric services in a public-sector community mental health setting so that resources will be used efficiently.

The guidelines are based on several assumptions. An FTE psychiatrist is contracted for 37.5 hours a week, or 2,250 minutes. Sixty percent of his or her time, or 1,350 minutes, is allocated to direct-care activities, and 40 percent, or 900 minutes, is allocated to indirect-care activities. Assessment of a new patient requires a total of 90 minutes—60 minutes for the interview and 30 minutes for documentation. The FTE psychiatrist performs three such assessments a week, for a total of 270 minutes.

Thus the time thus left for follow-up cases is 1,050 minutes (1,350 minutes minus 270 minutes). It is assumed that follow-up of a stable patient requires a total of 20 minutes—15 minutes for the patient interview and five minutes for documentation. Follow-up of an unstable patient requires 40 minutes—30 minutes for the patient interview and 10 minutes for documentation. The psychiatrist allocates 70 percent of the remaining 1,050 minutes, or 735 minutes, to stable cases and 30 percent, or 315 minutes, to unstable cases. Thus the psychiatrist can see 37 stable follow-up patients a week and eight unstable follow-up patients.

In this model, case allocation is determined by the service demands on each clinician and the proportional time commitment using the above guidelines. Based on the assumption that 60 percent of a psychiatrist's time should be allocated to direct care, each week an FTE psychiatrist should be able to see three new patients, 37 stable patients, and eight unstable patients. Workloads of psychiatrists working part-time sessions can be easily calculated using the above approach. The model does not include any indirect-care activities, for which 40 percent of the psychiatrist's time is allocated.

Discussion and conclusions

It is important to recognize that these benchmarks are working guidelines only, and that several assumptions have been made in the absence of clear data. Confounding variables, such as case mix and severity of illness, the program setting (for example, rural or urban), the availability of other nonphysician clinical resources and their expertise, and the needs of special client populations, must be taken into account when setting benchmarks. These factors are very difficult if not impossible to control—thus the need for built-in flexibility. However, some of these imbalances should even out over a period of time if the target population and workloads are similar for psychiatrists in similar settings.

We believe workloads rather than caseloads are a better indicator of clinical activities. We acknowledge the limitations of this method and emphasize the need for ongoing monitoring and evaluation until a dynamic balance is reached by a process of "successive approximations."

Resource allocation is closely linked to available funding and cutbacks, which in turn directly affect clinical services, the psychiatrist's workload, and the quality of care that the psychiatrist can provide. Unless we have guidelines for workload estimations based on acceptable standards of care and clinical outcomes, psychiatrists run the risk of spreading themselves too thin due to shrinking health care resources and increasing service demands. As Capen (4) warns, this situation can lead to a drop in service standards and quality of care, resulting in stress and liability risks for physicians.

Of particular importance is the fact that teaching, supervision of medical students and residents, and some degree of administration are essential roles for psychiatrists in a teaching hospital. Unfortunately, the importance of these activities is generally not recognized, and time and resources are not dedicated to them. A survey of part-time faculty in academic psychiatry by Charach and Leszcz (5) found that in the overall academic mandate, teaching and clinical services were undervalued compared with research and the ability to attract funding grants. In comparing themselves with tenured research faculty, part-time faculty were dissatisfied by the relative lack of recognition for educating students and providing training in clinical skills as well as by inadequate opportunities for promotion.

It is crucial that the concerns of part-time academic faculty be addressed by teaching hospitals, universities, and departments of health in collaboration. Attention to their concerns would definitely enhance job satisfaction and, more important, help with recruitment and retention of high-caliber psychiatrists in the public sector.

As community care gains momentum and we stride into the 21st century, the need for early intervention in psychiatric illness will continue to increase. The only way to ensure effective service delivery without compromising clinical standards is for psychiatrists, administrators, and health care planners to work together in setting and using benchmarks. With appropriate modifications, the guidelines presented here are broad enough to be applied to various clinical settings and programs. A similar approach can be used to set benchmarks for other clinical disciplines.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Jill Petrella, M.H.A., for help with data analysis.

Dr. Bhaskara is lecturer and staff psychiatrist at Nova Scotia Hospital, P.O. Box 1004, Pleasant Street, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada B2Y 3Z9 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Guidelines for establishing provisional benchmarks for allocating the time of a psychiatrist in a public-sector community mental health setting

1. Faulkner LR, Goldman CR: Estimating psychiatric manpower requirements based on patients' needs. Psychiatric Services 48:666-670, 1997Link, Google Scholar

2. Goldman CR, Faulkner LR, Breeding KA: A method of estimating psychiatrist staffing needs in community mental health programs. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:333-337, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Diamond RJ, Stein LI, Susser E: Essential and nonessential roles for psychiatrists in community mental health centers. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:187-189, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Capen K: Resource allocation and physician liability. Canadian Medical Association Journal 156:393-395, 1997Google Scholar

5. Charach A, Leszcz M: Part-time faculty in academic psychiatry: issues in satisfaction with role. Annals of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada 30:412-416, 1997Google Scholar