The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: Development and Implementation of the Schizophrenia Algorithm

Abstract

The Texas Medication Algorithm Project is a program designed to improve the quality of care of persons with serious mental disorders across sites in the Texas public mental health system and to create a uniform clinical environment from which cost estimates can be made. This paper describes the process of developing a pharmacological treatment algorithm for schizophrenia that addresses use of antipsychotics as well as other medications for side effects and co-existing symptoms. Input from clinicians, consultants, and consumers informed development of the algorithm, which was based on existing expert consensus guidelines. Information about the project can be found on the Internet at www.mhmr.state.tx.us/meds/tmap.htm. The authors present and describe the original and current versions of the algorithm, outline the feedback process by which it will be refined, and discuss how new medications will be incorporated as they enter the market.

The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) is a public-academic collaboration to improve care for patients in the public mental health system of Texas. This paper describes the project's development and implementation of a medication algorithm for schizophrenia and related disorders. This report focuses on phase 1 of TMAP, the initial development of the algorithm for schizophrenia. Phase 2, a study of feasibility of use, and phase 3, a comprehensive evaluation of the revised algorithm, will be reported in future papers. In addition, the logical and empirical bases for the evolution of the algorithm, which is now in its fourth version, will be reported in a future publication.

A detailed review of the conceptual basis for TMAP is presented elsewhere (1). The purpose of this paper is to present issues and experiences in the development of the schizophrenia algorithm for use in diverse treatment settings, not to promulgate the particular algorithm used in this project.

The project

In brief, TMAP is a public-academic collaborative endeavor to develop, implement, and evaluate medication treatment algorithms for public-sector patients in three diagnostic groups—those with schizophrenia, major depression (including psychotic depression), and bipolar disorder. The institutions involved are the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation; the departments of psychiatry at Texas Southwestern Medical College, the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston; and the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin. The schizophrenia algorithm was initially implemented at five sites within the Texas public mental health system, and a similar number of sites were used in implementing the other two algorithms. Currently, 17 sites are testing expanded and refined versions of these algorithms.

Initial steps inalgorithm development

Algorithm development and implementation took place in the fall of 1996 and systematically involved input from groups of clinicians, consultants, and consumers. Early in this process, the participants agreed to five general principles governing the development of the schizophrenia algorithm.

•The goals of the algorithm are to improve quality of care in the Texas public mental health system, to create a uniform clinical environment from which cost estimates can be made, and to provide data to inform revisions in the algorithm.

•The algorithm provides a sequential framework for clinical decision making. When possible, multiple options are available at a given stage so that the treatment plan can be tailored for optimal outcomes. Subsequent treatment is informed by the patient's response. Critical decision points define movement between stages.

•The DSM-IV diagnostic framework is necessary but not sufficient to establish the boundaries of the algorithm. Patients with chronic psychotic disorders for whom antipsychotic medications are the mainstay of treatment are the target population. Psychotic mood disorders are excluded, because they are addressed in the TMAP algorithm for major depressive disorder.

•Use of the algorithm for a given patient is determined by the physician's decision to change medication. A physician may initiate treatment for a patient at any stage of the algorithm.

•Participating physicians are required to use the algorithm or state their reason in a progress note for not doing so. These reasons become part of the database for revisions to the algorithm.

For several reasons, the initial algorithm for schizophrenia was limited to pharmacotherapy. First, the literature on medications provides significant evidence on which to base clinical consensus. Second, although medications constitute a small portion of the mental health budget, the increased costs of new medications have caused administrative scrutiny and, in many cases, have resulted in limitations on physicians' prescribing choices. Third, appropriate pharmacotherapy may decrease utilization of crisis services and increase the demand for psychosocial rehabilitation programs. Data from implementation of the medication algorithm might inform the development of uniformly applied, consensus-driven, psychosocial rehabilitation programs.

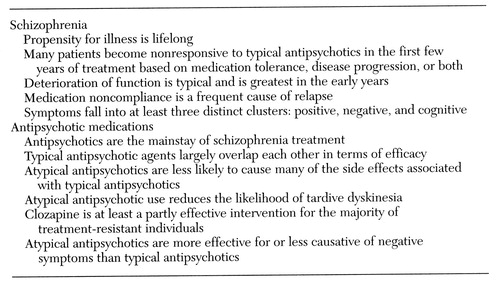

The basis in the literature for the algorithm was determined by a multistep process. First, the codirectors for development of the schizophrenia algorithm (the first and second authors) made explicit the "facts" about schizophrenia in which they had a great degree of confidence (Table 1). In compiling this list, the review compiled by the Schizophrenia Outcomes Research team (2) was particularly helpful.

Most of these facts are implicitly incorporated into the tri-university group's expert consensus guideline on schizophrenia (3), which is based on a survey of experts in the treatment of schizophrenia. This work was fundamental to our project and was presented at the initial TMAP meeting for the schizophrenia algorithm in September 1996. Participants—clinicians, consultants, and consumers—spent a full day discussing, digesting, and prioritizing the information on which the algorithm would be built.

The expert consensus guideline on schizophrenia is a statistically derived evaluation of the degree of consensus among experts (3). The guideline provided us with essential information but was limited by the finite number of questions and the forced-choice format within each question. Some questions important to us (such as identifying the best instruments to assess symptom change during treatment) were not addressed in the expert consensus guideline, and possible answers to some questions were not among the options from which the experts could pick.

For example, the question on drug tapering addressed dosage reduction in increments that might not have been chosen by the physicians polled. An open-ended question that asked for strategies for reducing dosage may have produced very different answers. In addition, the confidence-interval calculations showed a significant proportion of outlier opinions, even among experts. For example, 7 percent of the experts saw supportive dynamic individual psychotherapy as the treatment of choice during brief hospitalization for an acute psychotic episode, and 20 percent advocated an on-site outpatient pharmacy as a cost-effective way to manage treatment noncompliance.

Developers of the TMAP schizophrenia algorithm differed with the recommendation in the expert consensus guideline that high-potency antipsychotics are a first-line intervention and low-potency antipsychotics are a second-line intervention. The literature shows no difference in efficacy and suggests a slight increase in risk for akathisia, a significant factor in noncompliance, with high-potency medications. Low-potency agents have a higher incidence of sedation and cardiovascular side effects. Individual patient factors should affect a physician's decision to use one versus the other.

Construction of the algorithm

Immediately after the presentation of the expert consensus guideline at the September 1996 meeting, the schizophrenia module codirectors and clinical participants met to focus on procedural issues such as inclusion criteria, medication selection, and the use of adjunctive medications. This meeting occurred before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved olanzapine and before the publication of the American Psychiatric Association's Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia (4). These subsequent events highlight the need to integrate new information and treatment options into revisions of the algorithm. The decision-making process about the inclusion of olanzapine and other new drugs is discussed below.

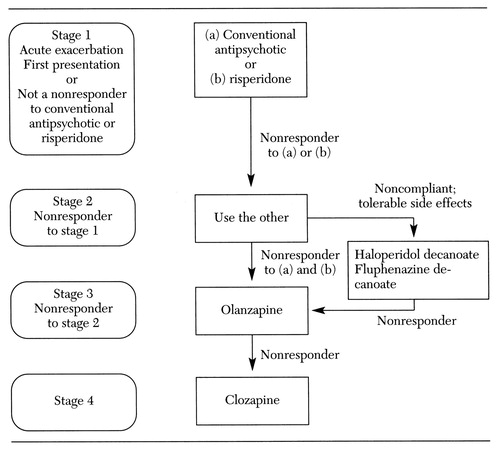

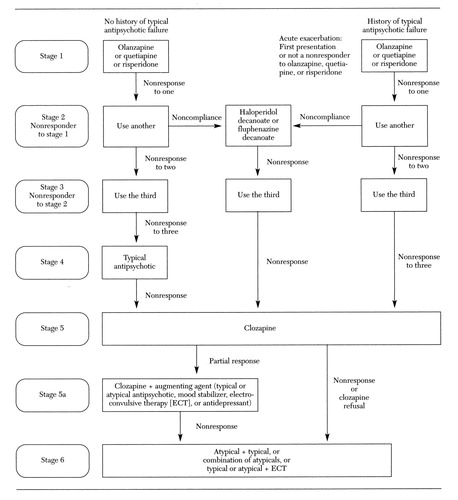

The treatment algorithm as it existed in the development phase is presented in Figure 1. The current version is presented in Figure 2. A physicians' instruction manual was developed to address implementation tactics and timing within and between algorithm stages. The current version of the manual is available on the TMAP Web site at www.mhmr.state. tx.us/meds/tmap.htm.

The staging of antipsychotic medication is a complex process. The psychiatric literature contains a broad array of parallel-group studies, and far fewer crossover studies that compare two or more agents. These comparisons focus on both the efficacy and the safety of various treatments. This information is helpful in determining which medications to include. However, the algorithmic process should not only limit the choices but also determine the optimal order in which to use them. Many aspects of pharmacological intervention are considered when addressing the latter issue.

In determining initial treatments, the logical process would be to begin with the most efficacious and best-tolerated drug available. There does not appear to be one clear choice for a first-line agent. Crossover studies have identified clozapine as the single most efficacious treatment, but the incidence of agranulocytosis, albeit low, precludes recommendation of clozapine as a first-line treatment option. The other atypical antipsychotics available for initial treatment—risperidone and, more recently, olanzapine—are well-tolerated medications that have not been found to cause agranulocytosis. The risks of long-term side effects, including tardive movement disorders, are less clear with both these agents. It is possible that these medications could have rare but serious long-term problems that have not yet been detected.

The selection of any medication as a first-line treatment involves a balance between efficacy, tolerability, and safety. The group's task was to limit choices in order to keep the model simple and at the same time provide a reasonable array of treatment options. Information from the state system's pharmacy was used as a database for antipsychotic prescribing. From these sources, we identified the ten most frequently prescribed antipsychotics. All participants agreed that this list provided sufficient options.

The discussion at the September 1996 meeting made clear that attentiveness to safety considerations would strengthen physicians' adherence to the algorithm. New medications would be considered second- or third-line agents or would not be put in the algorithm until their safety profiles in the general psychiatric population could be better established and physicians could be educated about their use. Between 3,000 and 5,000 carefully selected subjects participate in the stage II and III studies of new antipsychotic drugs coming to market. We assumed that it is necessary to treat approximately 40,000 patients in typical clinical settings to establish a medication safety profile. Safety can never be completely proven, but such an approach should identify serious adverse reactions with an occurrence rate as low as one in 10,000 patients.

Data have not yet been obtained on the impact on the course of schizophrenia of atypical antipsychotics that became available after clozapine. This lack of data is particularly significant for individuals whose presentation is dominated by negative symptoms. Evidence linking negative symptoms to poorer outcomes points to the potential value of early intervention with the newer antipsychotics. There is some indication that atypical antipsychotic treatment may change outcomes (5,6).

In the original algorithm (see Figure 1), clinicians chose from the list of available conventional antipsychotics or risperidone. If one of these options failed, the other option was instituted before treatment with olanzapine. Clozapine was reserved for patients who were not responsive to the other treatment options. When patients were noncompliant with medications for reasons other than intolerable side effects, clinicians were guided to choose either haloperidol decanoate or fluphenazine decanoate. The next choice was olanzapine and then clozapine for the persistently treatment-resistant patient. The current algorithm (Figure 2) incorporates new medications and safety data and includes postclozapine strategies.

A medication algorithm must also address treatment of the most clinically significant side effects, and an algorithm was developed for this purpose (see TMAP Web site). The side effects addressed are extrapyramidal symptoms, akathisia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and tardive dyskinesia.

An algorithm for the common associated symptoms of insomnia, agitation, and depression was also developed and can be found on the Web site.

Substance abuse is a common comorbid condition with schizophrenia, but it has not been addressed at this time primarily because of the great variability of substance abuse treatment resources across the Texas sites. Physicians must attempt to treat schizophrenia regardless of the patient's substance abuse or dependence, and these patients were not excluded from consideration. This issue is considered part of routine clinical management, and the instructions in the physicians' manual are that if substance abuse or dependence exists, it should be treated.

The duration of treatment specified in the expert consensus guideline (3) was incorporated into the algorithm with minor modifications. Criteria about treatment response, whether adequate, partial, or resistant, are not addressed but are of obvious importance in a project that seeks to improve outcomes. Unfortunately, criteria for treatment response that are widely used in schizophrenia research, such as a 20 percent decrease in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) score (6), have not been tested for feasibility or suitability in ordinary clinical settings.

For the initial studies of the TMAP schizophrenia algorithm, we obtained patients' scores on the BPRS and physicians' and patients' ratings using the Clinical Global Impression scale and encouraged clinicians to exercise their best clinical judgment about when to adjust or change medications. This process allowed us to establish a database to analyze the relationships between psychometrically based clinical ratings and physicians' decision making about medications.

The expert consensus guideline on schizophrenia included psychosocial intervention as well as medication intervention (3). An integration of pharmacological and psychosocial approaches is clearly desirable. Certainly, strong evidence is available for the efficacy of a variety of psychosocial interventions. However, recommendations on use of psychosocial interventions were not included in the algorithm for two reasons. First, considerable variability exists across sites in the availability of different psychosocial programs, whereas the same medications are available at all sites. Second, there is little information on optimizing combined drug and psychosocial treatments on which to base algorithms for both. Therefore, in phases 1 and 2 of TMAP, clinicians use their best judgment about which psychosocial intervention to use and when in the course of treatment it should be used.

Implementation of the algorithm

Once TMAP was launched in October 1996, the schizophrenia module codirectors held weekly conference calls with site participants—hospitals and clinics in El Paso, the Rio Grande Valley, San Antonio, Houston, and Lubbock. The content of the discussions became part of the data for revision of the algorithm. The most frequent deviations discussed were length of treatment within stages. The content of the calls fell into three broad categories: administrative issues, clinical issues, and site-specific problems. Minutes of each call were circulated among all participants. The module codirectors were available every day by telephone for consultation and feedback.

The conference calls identified several questions that this algorithm and other medication algorithms for schizophrenia need to address: What are the best medication choices for patients who do not respond fully to clozapine? What should the clinician do when clozapine-responsive patients want to try a new antipsychotic? What are the optimal tapering and dosage-increasing regimens in switching from one antipsychotic to another, especially in switching from a typical to an atypical or from clozapine to another atypical?

Early in the course of the feasibility trial, the physicians participating in the teleconferences requested additional education, in part because several sites had had restrictive formularies that limited physicians' experience with newer medications. For example, physicians had questions about monitoring of adverse effects, drug interactions, and switching and overlapping antipsychotics. These and other topics were addressed in a day-long program offered by the module codirectors two months after the feasibility trial began.

Conclusions

The processes discussed in this paper led to the successful development and pilot testing of an algorithm for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia at diverse public-sector sites. Consensus building and ongoing clinical consultation are key ingredients. State mental health agencies must answer to a variety of constituents and concerns, and a program that demonstrates attention to input from clinicians, administrators, and advocates stands a better chance of getting the broad-based government and private support the TMAP algorithm has received.

It is imperative to recognize that medication algorithms for treatment of schizophrenia will continue to need periodic revisions. New treatments, data, and feedback information from the current model will be incorporated. New documents, such as the American Psychiatric Association's Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia (4), will also help guide revisions. One way of rapidly communicating these revisions to those interested is via the Internet, which is the purpose of the TMAP Web site (www.mhmr.state. tx.us/meds/tmap. htm).

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Meadows Foundation, Moody Foundation, Nannie Hogan Boyd Charitable Trust, Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institute of Mental Health (grant MH-53799), Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Eli Lilly and Company, Glaxo-Wellcome, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Pfizer, Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, as well as Mental Health Connections, a partnership between the Dallas County Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation and the department of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School. Funding is also provided by the Texas State Legislature and the Dallas County Hospital District.

Dr. Chiles and Dr. Miller are professors and Ms. Krasnoff is a social science research associate in the department of psychiatry at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, Texas 78284-7792 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Crismon is professor and Southwestern Drug Corporation centennial fellow in pharmacy at the College of Pharmacy of the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Rush holds the Betty Jo Hay Distinguished Chair in Mental Health and is professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Dr. Shon is medical director of the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation in Austin.

Figure 1. Initial version of the algorithm for pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia

Figure 2. Current version of the algorithm for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia

|

Table 1. Basic assumption about schizophrenia and antipsychotic meditcations used by developers of the Texas Medication Algorithm project's algorithm for schizophrenia

1. Gilbert DA, Altshuler KA, Rago WV, et al: Texas Medication Algorithm Project: definitions, rationale, and methods to develop medication algorithms. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59:345-351, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lehman A, Thompson J, Dixon L, et al: Schizophrenia: treatment outcomes research: editors' introduction. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:561-566, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA: The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 12B):1-58, 1996Google Scholar

4. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(Apr suppl):1-63, 1997Google Scholar

5. Keith SJ: Pharmacologic advances in the treatment of schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 337:851-852, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J: Appendix A: Manual for the expanded BPRS in rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:594-0602, 1986Google Scholar