The Role of the Psychiatrist as Program Medical Director

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In a recently published survey of alumni of the Columbia University public psychiatry fellowship, respondents who were medical directors reported performing a greater variety of tasks and experiencing higher job satisfaction than those who were staff psychiatrists. Both medical directors and staff psychiatrists believed that job satisfaction was most dependent on clinical collaboration activities. Survey data were reanalyzed to determine whether there was a relationship between the frequency of tasks performed and overall job satisfaction, and whether the tasks that actually predicted overall job satisfaction were the same as those that respondents believed contributed to job satisfaction. METHODS: The survey was distributed to all public psychiatry fellows and alumni in active practice (N=89), and 72 forms (81 percent) were returned. The survey consisted of 16 self-administered items divided into three categories of job tasks: direct service, clinical collaboration, and administration. Results and conclusions: Despite respondents' beliefs that clinical collaboration activities contributed most to job satisfaction, performance of administrative tasks was found to best correlate with overall job satisfaction. Furthermore, overall job satisfaction was related to the performance of administrative tasks and not to the job title of medical director alone. Most of the medical directors in the survey had program-level, rather than agency-level, responsibilities. The findings indicate that the role of program medical director can serve as a crucial next step for staff psychiatrists, offering the opportunity to perform administrative tasks, which, according to the results, improves job satisfaction in public-sector positions.

The role of psychiatrists in community-based mental health organizations has received extensive attention in the literature over the past 25 years. The major point of these discussions has been that to the extent that psychiatrists ceased to occupy leadership positions in these organizations, they experienced widespread dissatisfaction with their roles. However, an important development that has received insufficient attention is the emergence of a new leadership role for psychiatrists during this period, the position of medical director.

In President Kennedy's landmark 1963 Community Mental Health Centers (CMHCs) Act, it was assumed that CMHCs would be run by psychiatrists, as had the state hospitals before them. Indeed, the original mandate for the National Institute of Mental Health required that CMHCs be directed by psychiatrists, but this mandate was quickly broadened to include other mental health professionals (1). In fact, although more than half of CMHCs (55 percent) were headed by psychiatrist administrators in 1971 (2), the proportion of CMHCs run by psychiatrists dropped rapidly to 26 percent in 1977 (3) and to 8 percent in 1985 (4). This trend was undoubtedly facilitated by the community mental health movement's well-documented shift from the medical model to the social model during that period (5).

Notwithstanding this shift, some CMHCs recognized the need for psychiatric oversight and began to appoint psychiatrists as medical directors. For example, a survey conducted in the early 1980s of executive directors of Oregon community mental health programs, none of whom were psychiatrists, reported that 18 percent of the CMHCs employed psychiatrists as medical directors (6).

The American Association of Community Psychiatrists (AACP) was founded in 1984 with the explicit mandate to "establish and define the role of psychiatrists in community programs" (7). In 1986 the AACP developed guidelines for psychiatric practice in CMHCs, including a job description for the role of medical director (8). With the approval of these guidelines in 1991 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) (9), it became the official position of APA that all mental health centers should have medical directors with clinical leadership roles (10). In fact, by the early 1990s, a total of 142 of 214 CMHCs responding to a survey (66 percent) reported having job descriptions for a medical director (11).

Diamond and colleagues (12) noted several factors that have led to this re-emerging leadership role for psychiatrists, including an increasing focus on treatment of persons with serious mental illness and insistence by state agencies and third-party payers that psychiatrists supervise treatment provided by nonmedical staff.

Despite increased attention to the role of medical director, there is ample evidence that the position remains marginalized. In 1996 Young and Clark (13) reported that "many CMHCs currently function with little clinical care or leadership from psychiatrists." A position paper published by the North Carolina district branch of the APA in 1992 (14) noted that "the position of Medical Director was once recognized in state statutes but was deleted in 1977. A number of centers have no position for a medical director… in others the position of medical director is filled by a part-time consultant… isolated from the supervision of clinical staff and uninvolved in the organization of service delivery programs."

The role of program medical director

A possible strategy for dealing with the marginalization of medical directors and the limited involvement of staff psychiatrists in CMHCs is the development of the position of program medical director. In contrast to the more well-known agency-level medical director, a program medical director is a psychiatrist who has supervisory responsibility at a program level (for example, at a day hospital) or at a team level. Some articles published more than ten years ago discussed the desirability of psychiatrists' having leadership roles on teams but did not refer to them as program medical directors (3,15). More recently, Young and Clark (13) suggest that the primary psychiatrist for a day treatment program should be designated as medical director of that program.

Similarly, the lead author of the 1992 North Carolina position paper (14) recently commented, "We noted a similar need to identify a sphere of authority and responsibility for the staff psychiatrist as 'program medical director'" (Ames DA, personal communication, Dec 1997). Finally, Diamond and associates (12) identified the position of "team medical director who is administratively co-equal to the team leader."

For this strategy to be viable, psychiatrists need to be aware of the possibility of filling such positions—and, in some cases, creating them—and they need to be knowledgeable about the types of activities these positions entail. Furthermore, they should be aware that the assumption of these responsibilities can increase job satisfaction, and, specifically, they should understand which responsibilities are most likely to improve job satisfaction. In a 1996 survey of Columbia University's public psychiatry fellowship alumni, respondents were asked to rate the importance of various activities in contributing to their job satisfaction (16). Activities were examined in terms of tasks categorized in three groups: direct service to patients, clinical collaboration, and administration. More than half of the 72 respondents (58 percent) were employed as medical directors. Of these, 38 (90 percent) were working as program medical directors.

Respondents who were medical directors reported performing a greater variety of tasks and experiencing higher job satisfaction than those who were staff psychiatrists. Both medical directors and staff psychiatrists believed that job satisfaction was more dependent on participation in clinical collaboration tasks than in direct service or administration. (The 1998 version of the survey form can be viewed on the fellowship's Web site at http://cpmcnet.columbia.edu/dept/pi/ppf/. Readers are invited to complete the survey form, as we are currently collecting data from a larger sample.)

This finding about satisfaction is consistent with other literature suggesting that psychiatrists generally attribute considerably more importance to clinical collaboration than administration in their assessments of job satisfaction. In 1984 Beigel (17) noted that in CMHCs in which psychiatrists experienced job satisfaction and remained actively involved, those "psychiatrists devoted significantly more time to clinical care (as opposed to administration)." Similarly, in their 1985 survey of 220 psychiatrists working in CMHCs, Clark and Vaccaro (18) reported that the 14 psychiatrists who expressed most satisfaction with their CMHC focused on clinical collaboration rather than administrative activities. These 14 psychiatrists identified five factors as contributing most to job satisfaction—three were related to performance of clinical collaboration tasks, and only one was related to performance of administrative tasks.

Clearly, medical directors perform a combination of clinical collaboration and administrative tasks, and the question arises of whether administrative activities actually decrease job satisfaction. With this in mind, we reanalyzed the data from our survey (16) to investigate further the relative contributions of clinical collaboration and administrative tasks in contributing to job satisfaction. In particular, we decided to explore the relationship among three variables: the frequency with which psychiatrists perform direct service, clinical collaboration, and administrative tasks; their beliefs about the contribution of these three task domains to job satisfaction; and their actual ratings of overall job satisfaction.

Methods

A survey was distributed to all public psychiatry fellows and alumni in active practice (N=89) in 1996. Seventy-two forms (81 percent) were returned. Three respondents were in full-time private practice, and 69 were in public institutional settings. Of the 69 in the public sector, 42 were medical directors, and 27 were staff psychiatrists.

The survey consisted of 16 self-administered items divided into three subgroups: direct service (four items, including providing medication, providing psychotherapy, overseeing medical care, and negotiating care with other providers); clinical collaboration (five items, including supervising medical and nonmedical staff, providing informal consultations, participating in team meetings, and conducting formal training); and administration (seven items, including policy development, routine administration, quality assurance, contract negotiation, and linkage to outside agencies, regulatory bodies, and boards).

For each of the items, the respondent was asked to rate the frequency with which that task was performed and the degree to which that task contributed to job satisfaction. Scales were created for each of the three subgroups by calculating the mean of the items on that subscale. Indicators of internal consistency reliability were acceptable. For task frequencies, the Cronbach alphas were .55 for direct service, .67 for clinical collaboration, and .81 for administration; for contribution to job satisfaction, they were .57 for direct service, .60 for clinical collaboration, and .75 for administration. Respondents were also asked to rate overall job satisfaction separately from the above ratings on individual tasks.

We performed correlational and regression analyses to examine the relationship between the frequency with which respondents performed direct service, clinical collaboration, and administrative tasks and the two sets of satisfaction-related outcome measures: psychiatrists' beliefs about the contribution of each task domain to job satisfaction and their actual ratings of job satisfaction.

Results

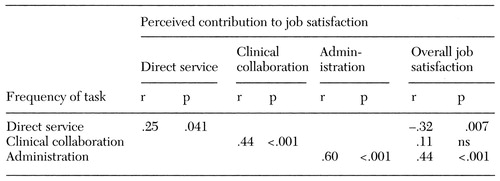

Table 1 shows the correlations between respondents' frequency of involvement in each type of task and their perceptions of how much the task contributed to satisfying work. Positive associations were found between task frequency and perceived contribution to job satisfaction for each of the three task types. The more psychiatrists reported engaging in direct service, clinical collaboration, or administrative activities, the more they viewed these tasks as contributing to overall job satisfaction.

However, the magnitude of the correlations varied, from a low of .25 for direct patient service to a high of .60 for administration. That is, respondents' beliefs about the importance of administrative tasks to job satisfaction were more closely tied to their current involvement in such activities than were their beliefs about the importance of direct service; their beliefs about clinical collaboration were in an intermediate position.

Table 1 also shows Pearson correlations between overall job satisfaction and each of the task frequency scales. In contrast to the findings described above and contrary to expectation, job satisfaction was negatively associated with frequency of direct service provision, not significantly associated with frequency of clinical collaboration, and positively associated with frequency of performing administrative tasks.

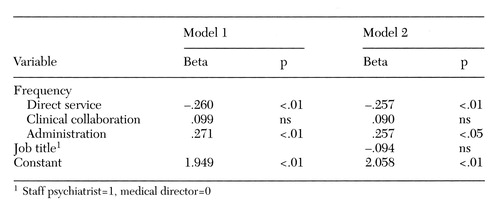

To further examine the relationship between job satisfaction and involvement in direct service, clinical collaboration, and administrative tasks, we regressed the variable of overall job satisfaction on the three task frequency scales (see model 1 of Table 2). Results parallel the correlational findings. Psychiatrists who reported less involvement in direct service tasks and greater involvement in administrative tasks tended to report greater job satisfaction, but the frequency of performing clinical collaboration tasks was not related to job satisfaction.

Finally, in our previous paper (16), we observed that medical directors reported greater overall job satisfaction than staff psychiatrists and also noted the directors' more frequent involvement in each type of task. We raised the question of whether higher levels of job satisfaction among medical directors can be explained by their greater involvement in the three sets of activities, or whether the position of medical director confers additional sources of job satisfaction, such as higher salary, visibility, and prestige.

To investigate this question, we added job title to the regression analysis (0=medical director, 1=staff psychiatrist; see model 2 of Table 2). As model 2 shows, job title was not significantly associated with job satisfaction once frequency of involvement in the three tasks was controlled. Controlling for task frequency reduced the relationship between job title and overall job satisfaction (from beta=-.74, p<.01 to beta=-.09, p>.10)(data not shown in Table 2).

We also investigated whether the associations between job satisfaction and involvement in direct service, clinical collaboration, and administration differ for medical directors and staff psychiatrists by adding cross-product interaction terms into the equation. None of the interactions was statistically significant (data not shown), indicating that the relationship between task involvement and job satisfaction was not contingent on job position.

Discussion

Results presented in our previous paper (16) suggested that psychiatrists in public-sector positions believe that involvement in clinical collaboration contributes more to job satisfaction than involvement in direct service or administrative activities. Results presented here add two qualifications about respondents' perceptions: the more psychiatrists are currently engaged in a domain of activity, the more likely they are to view the activity as contributing to job satisfaction, and the link between current task involvement and perceptions of its contribution to overall job satisfaction is stronger for administrative tasks than for clinical collaboration or direct service activities.

However, actual job satisfaction showed quite different associations with task frequency than did perceptions of task importance. Job satisfaction for both medical directors and staff psychiatrists was positively related to participation in administrative activities and negatively related to involvement in direct service tasks. Contrary to the respondents' perceptions, job satisfaction was unrelated to the level of involvement in clinical collaboration tasks. Furthermore, medical directors' greater job satisfaction, compared with that of staff psychiatrists, can be explained by differences in tasks performed, especially by medical directors' greater involvement in administrative tasks, and not by the job title itself.

Our most important finding is that despite our respondents' belief that the performance of clinical coordination tasks contributed most to job satisfaction, it is in fact the performance of administrative tasks that was most highly correlated with overall job satisfaction. The most likely explanation for this finding is a mediating factor—the correlates of power (respect, freedom to act, ability to influence others, and possibly higher income). Psychiatrists are notoriously loathe to admit they like to exert power. Furthermore, clinical collaboration tasks carry higher prestige in the profession than do administrative tasks, thus fostering beliefs about their importance for job satisfaction.

It is worth noting that psychiatrists are undoubtedly more knowledgeable about and have more experience with direct service and clinical coordination than administrative tasks. Thus their perceptions about the importance of the these two task domains for job satisfaction are not that closely tied to their current levels of involvement. By contrast, psychiatrists may not realize how much administrative tasks can contribute to job satisfaction until they experience performing them in their work.

The correlation between task frequency and job satisfaction for each of the three task types is intriguing. It is difficult to see why performing a task more often would increase the extent to which that task contributes to job satisfaction. It is more likely that psychiatrists are able to perform the tasks that contribute to job satisfaction more often. If so, this finding suggests considerable job autonomy, a factor that may also need to be addressed in further surveys.

The demonstration that overall job satisfaction is related to the actual performance of administrative tasks and not the job title of medical director has important implications. In our previous paper, we commented that most of our survey respondents who are medical directors ran programs (rather than agencies), and that many of these directors actually created their own jobs while negotiating for positions as staff psychiatrists. The results of this survey suggest that if staff psychiatrists assume the administrative responsibilities of program medical directors, they can expect to improve their job satisfaction even if they do not secure the actual title. It appears that the medical director title provides the increased opportunity to perform administrative tasks, but staff psychiatrists who accept these administrative responsibilities report just as much overall job satisfaction as do those with the title of program medical directors.

Conclusions

Most of the medical directors in our survey had program rather than agency responsibilities. Our review of the literature revealed that the concept of program medical director has received recent attention. What has not been reported thus far, however, is the recognition that the role of the psychiatrist as program medical director can serve as a crucial parameter of job satisfaction, insofar as it gives the psychiatrist the opportunity to perform administrative tasks.

Our findings suggest that the position of program medical director can be a valuable next step for staff psychiatrists who wish to improve their own sense of involvement with their community mental health agency. These findings are especially important because an agency usually has only one agency medical director, but it can potentially have one program medical director for each program in the agency.

Furthermore, the survey can be viewed as a source of encouragement for psychiatrists who function in systems that are not flexible enough to allow the designation of program medical director. Clearly, psychiatrists can, and should, create their own roles while functioning in public-sector organizations. The results of our survey suggest that the performance of a wider variety of tasks, especially administrative tasks, leads to greater job satisfaction, taking us a significant step toward the goal of improved job recruitment and retention for psychiatrists in the public sector.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephen Rosenheck, M.S.W., and Susan Deakins, M.D., for their helpful comments.

Dr. Ranz is director of the public psychiatry fellowship and associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and the New York State Psychiatric Institute, 722 West 168th Street, Box 111, New York, New York 10032 (e-mail: [email protected]). Dr. Stueve is assistant clinical professor of public health (epidemiology) in the division of epidemiology of the School of Public Health at Columbia University.

|

Table 1. Correlations between the frequency of performing three types of tasks and the perceived contribution of the tasks to job satisfaction among 72 medical directors and staff psychiatrists

|

Table 2. Linear regression analysis of overall job satisfaction on frequency of tasks performed and job title for data from 72 medical directors and staff psychiatrists

1. Winslow WW: The changing role of psychiatrists in community mental health centers. American Journal of Psychiatry 136:24-27, 1979Link, Google Scholar

2. Pollack DA, Cutler DL: Psychiatry in community mental health centers: everyone can win. Community Mental Health Journal 28:259-267, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ribner DS: Psychiatrists and community mental health: current issues and trends. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 31:338-341, 1980Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Knox MD: National register reveals profile of service providers. National Council News (National Council of Community Mental Health Centers), Sept 1985, p 1Google Scholar

5. Sharfstein SS: Will community mental health survive in the 1980s? American Journal of Psychiatry 135:1363-1365, 1978Google Scholar

6. Faulkner LR, Bloom JD, Bray JD, et al: Psychiatric manpower and services in a community mental health system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:287-291, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Breakey WR: Modern community psychiatry, in Integrated Mental Health Services. Edited by Breakey WR. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

8. AACP Guidelines for Psychiatric Leadership in Organized Delivery Systems for Treatment of Psychiatric and Substance Disorders. Community Psychiatrist 9(4):6-7, 1995Google Scholar

9. Guidelines for psychiatric practice in CMHCs. Psychiatric News, Apr 5, 1991, p 32Google Scholar

10. Clark GH: Psychiatrists' roles in CMHCs (ltr). Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1260, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Diamond RJ, Goldfinger SM, Pollack DA, et al: The role of psychiatrists in community mental health centers: a survey of job descriptions. Community Mental Health Journal 31:571-577, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Diamond RJ, Stein LI, Schneider-Braus K: Administration: the psychiatrist as manager, in Integrated Mental Health Services. Edited by Breakey WR. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

13. Young AS, Clark GH: Guidelines for community psychiatric practice, in Practicing Psychiatry in the Community. Edited by Vaccaro JV, Clark GH. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996Google Scholar

14. Community Mental Health Psychiatry Committee: The Psychiatrist's Role in the North Carolina Community Mental Health Program. Raleigh, North Carolina Psychiatric Association, Mar 1992Google Scholar

15. Diamond H, Cutler D, Langsley D et al: Training, recruitment, and retention of psychiatrists in CMHCs: issues and answers, in Community Mental Health Centers and Psychiatrists. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association and National Council of Community Mental Health Centers, 1985Google Scholar

16. Ranz JM, Eilenberg J, Rosenheck S: The psychiatrist's role as medical director: task distributions and job satisfaction. Psychiatric Services 48:915-920, 1997Link, Google Scholar

17. Beigel A: The remedicalization of community mental health. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:1114-1117, 1984Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Clark GH, Vaccaro JV: Burnout among CMHC psychiatrists and the struggle to survive. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:843-847, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar