Psychiatric and Psychological Predictors of Self-Reported Health of African Americans With Severe Mental Illness

The shift to community mental health care and associated decentralization and diffusion of services have placed people with severe mental illness at increased risk of not receiving adequate general medical care ( 1 ). Persons with severe mental illness have a higher risk of physical morbidity and mortality than the general population ( 2 ). Moreover, there are racial disparities within this high-risk population, with African-American psychiatric patients being at greater risk than their European-American counterparts ( 3 ). Greater attention needs to be devoted to the general health of persons with severe mental illness. At a minimum, programs and services for this psychiatric population, especially African-American patients, should include some basic assessment of overall health status.

Collecting self-report data is the most efficient and cost-effective method of obtaining health information about individuals with mental illness, given the possible lack of continuity of care from the multiple settings that may provide services to them ( 4 ). One of the most common measures of self-reported health is a rating of global health. Although self-report is the most efficient means of obtaining health information, it is also highly susceptible to reliability and validity problems because of biased responses. Issues of reliability and validity may be further compounded by mental health status and other psychosocial variables. Krause and Jay ( 5 ) found, for example, that single-item measures of global health may reflect different dimensions of health status for different racial-ethnic groups.

A significant association between mental health functioning and self-report of health status has not been consistently found in the literature ( 4 , 5 , 6 ). To date, however, no studies have sought to determine whether psychiatric symptoms measured via objective assessments may have differential effects on self-reported health status compared with subjective measures of psychopathology. Demographic variables, including race and ethnicity, gender, age, and education, are also associated with self-report of health problems ( 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). Moreover, Calhoun and associates ( 8 ) made the point that the correlation between psychiatric disorders and self-reported health status may be mediated by demographic variables that serve as proxies for access to general medical care and poor nutrition.

Another potential confounder in the relationship between psychiatric symptoms and global self-ratings of health are psychological factors. Psychological factors are nonclinical characteristics that may be correlated with psychopathology and become psychiatric symptoms in their extreme form. For example, self-esteem is a typical psychological factor that is related to having a psychiatric disorder, as well as to self-perceptions of health. An approach to the study of health assessments for persons with severe mental illness is needed that estimates the separate effects of demographic variables, psychological factors, and psychiatric symptoms.

The purpose of the study was to determine the effects of psychiatric symptoms, psychological factors, and demographic variables on the global self-reports of health status by African-American psychiatric patients. Not only were the effects of these variables on self-reported health examined, but different models of the relationship with the predictor variables were assessed with structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM is a form of path analysis with latent variables that are used to represent causal relationships in multivariate data ( 9 ). The latent construct for health status was the dependent variable measured with the observed variable of global self-rating of health. The two main questions that the study sought to answer were first, do psychiatric symptoms, psychological factors, or demographic background variables influence the self-reported health status of patients who are African American and have a schizophrenia diagnosis? Second, what is the best model of the impact of these factors in terms of their impact on self-reported health status? My primary hypothesis was that psychological factors and psychiatric symptoms would have differential effects on global self-reported health among African Americans with severe mental illness. A secondary hypothesis was that objective measures rather than subjective measures of psychiatric symptoms would better predict the impact of psychiatric symptoms on self-reported health status.

Methods

Patient sample

A total of 285 African-American patients at a public psychiatric hospital in upstate New York were available for participation in the study during the study period (June 1998–April 1999). They were considered eligible if they were between the ages 18 and 59, if they self-identified as persons of African descent and were U.S. citizens or immigrated before the age of 14, if they were not experiencing a severe psychotic episode at the time of the interview, and if they did not require the permission of a legal guardian to participate. Only 218 patients met all of these eligibility criteria, and 13% of the 285 (N=36) were ineligible and 11% (N=31) were discharged before being interviewed. Participation status for the 218 eligible patients was 141 agreed (65%), 56 refused (26%), 15 positive conversions (6%), and seven negative conversions (3%). (Positive conversions were patients who initially refused but then agreed to participate, and negative conversions were those who first agreed and later decided not to participate in the study.) Participants and nonparticipants were compared on several demographic variables to assess participation bias. Compared with female patients (56%), more male patients (76%) tended to agree initially to participate. However, the gender difference disappeared when refusers were compared with the positive converters. Those who agreed also did not differ significantly from refusers in terms of age, marital status, veteran status, type of admission (new or readmission), police involvement, or involuntary admissions ( 10 ). An overall 71% participation rate in the screening interview yielded a sample of 156 African-American patients. The data for 151 (97%) patients were used in this study. According to intake diagnoses, 56% (N=85) of the sample had schizophrenia and 44% (N=66) had other psychotic disorders. The gender distribution of the sample was 69% male (N=104) and 31% female (N=47). The mean±SD age of the sample was 39.42±9.41, and years of education were 10.69±1.69.

Measures

Self-reported health status. A general question asked during the screening interview was, "How would you describe your physical health?" Response options were poor, scored 1; fair, 2; good, 3; and very good, 4.

Psychological factors. Four observed variables represented the latent construct of psychological factors in the SEM model. The scale of distrust (DST), a five-item measure reflecting the mild end of the paranoia continuum, and need for approval, a scale of social desirability, were taken from the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI) ( 11 ). The 48-item Cultural Mistrust Inventory (CMI) measures African Americans' distrust of whites in the domains of business and work, education and training, interpersonal relations, and politics and law ( 12 ). The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale is a ten-item measure of self-esteem ( 13 ). Total scores on the DST (possible range 0–4), need for approval (possible range 0–2), CMI (possible range 1–7), and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (possible range 1–5) yielded adequate internal consistency reliability ( 14 ).

Psychiatric symptoms. The latent construct of psychiatric symptoms consisted of three subjective measures and two objective measures. The subjective measures were a continuum of moderate to severe paranoia reflected in the scales of perceived hostility of others (PHO) and false beliefs and perceptions (FBP) from the PERI and the Fenigstein Paranoia Scale, which is a measure of nonclinical paranoia ( 11 , 15 ). Total scores for the PHO (possible range 0–4), FBP (possible range 0–4), and Fenigstein scale (possible range 1–5) had adequate internal consistency reliability in the sample ( 14 ). The objective measures were total intake symptoms, computed by summing the presence (scored 1) or absence (scored 0) of 17 preselected symptoms, which psychiatrists recorded during intake diagnoses and screening interviewers abstracted from charts, and total symptom scores from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) ( 16 ), which were derived from the number of delusions and hallucinations at threshold level or at symptom level (in other words, they were clinically significant). The objective measures of psychiatric symptoms have also been shown to have adequate reliability in previous research ( 17 , 18 ). Moreover, low agreement between the psychiatric intake interviews and SCID interviews at both the syndrome (k=.11) and symptom (r=.10) levels justifies treating the two objective measures of psychopathology as orthogonal variables in the SEM equation.

Procedure

The data were collected originally for the Culturally-Sensitive Diagnostic Interview Research Project, and the procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Each participant was screened by one of two doctoral-level African-American clinical psychologists. After obtaining verbal consent from potential participants, the screening interviewer administered a brief mental status examination to assess patients' capacity to give written consent and to participate in the study. Subsequently, the interviewers orally administered the protocol of self-report scales, including measures of substance abuse, paranoia, cultural mistrust, and self-esteem. Interviewers completed the protocol with a debriefing statement and payment of $5 to patients for study participation. Interviewers then conducted a review of the patient's chart to abstract information on diagnosis, signs and symptoms of psychopathology, and medical history. All chart reviews were conducted after the face-to-face interviews to minimize bias. Eligible participants who completed the screening interview and independently signed another consent form received the SCID usually within a week of the screening interview. Master's-level psychologists who were unaware of responses in the screening interview and the study hypotheses performed the SCID interviews. Upon completion of the interview, participants were paid $15 for their participation or for the amount of time spent prorated at $5 per hour for incomplete interviews.

Statistical analysis

SEM was applied to several models by using AMOS 16.0 to select the measurement model with the best fit to the data. The input data were an unbiased covariance matrix that was analyzed by maximum likelihood estimation. Model testing involved the estimation of the effects of demographic characteristics (gender, age, and education), psychological factors (distrust, need for approval, cultural mistrust, and self-esteem), and psychiatric symptoms (PHO, FBP, Fenigstein scale, total SCID symptoms, and total intake symptoms) on global self-reported health status. All of the self-report measures were orally administered in a single instrument during the screening interview so they are assumed to have shared error variance. Fit indexes with cutoff values of χ2 /df<2.00, root mean square residual (RMR) <.05, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) >.90, comparative fit index (CFI) >.90, and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) <.05 were used to estimate goodness of fit for the best model. These indexes and cutoffs were selected because research suggests that they are among the best to determine the goodness of fit for measurement models in SEM ( 9 , 19 , 20 , 21 ). Standardized regression coefficients for the best measurement model provide an estimate of the effects of each latent factor on self-reported health status, as well as the strength of relationship between the observed variables and the respective latent factors.

Results

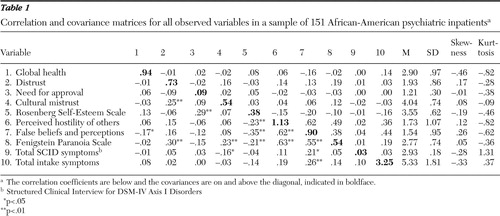

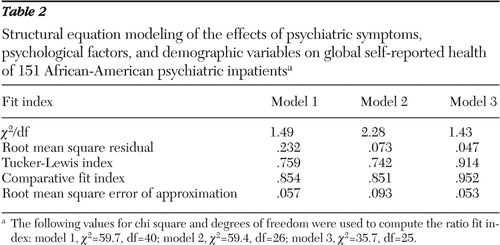

Correlation and covariance matrices with the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis values for all observed variables are presented in Table 1 . Only SCID symptom scores required logarithmic transformation to approximate normality. Model 1 tested the independent effects of psychiatric symptoms, psychological factors, and demographic variables. Model 2 examined the effects of psychiatric symptoms and psychological factors as independent latent constructs. Model 3 tested the effects of psychiatric symptoms and psychological factors as correlated latent constructs. The fit indexes from the tests of these models are summarized in Table 2 .

|

|

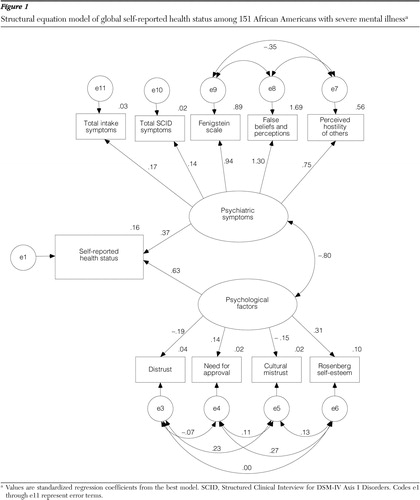

The best model included psychiatric symptoms and psychological factors as correlated latent constructs without demographic characteristics in the model. The removal of demographic variables improved model fit with χ2 /df=1.43, RMR=.047, TLI=.914, CFI=.952, and RMSEA=.053 (90% confidence interval=.00–.09). This model is depicted in Figure 1 with standardized regression coefficients. Psychological factors ( β =.63) had more of an impact than psychiatric symptoms ( β =.37) on patients' self-report of health status. The measures of self-esteem and lack of trust (specifically, distrust and cultural mistrust) were more representative of the latent construct for psychological factors than need for approval. Psychiatric symptoms as a construct yielded the largest coefficients for the FBP scale and the Fenigstein scale followed by PHO and yielded the smallest coefficients for the objective measures of total SCID symptoms and total intake symptoms.

Discussion

This study used SEM to examine the effects of psychological factors, psychiatric symptoms, and demographic background on self-reported health status among African-American psychiatric patients. The results indicated that patients' reports of their health status were influenced by these independent variables. The best model to fit the data was one with no demographic variables, and it correlated latent constructs for psychological factors and psychiatric symptoms. Consistent with the first hypothesis, the latter two latent constructs had a differential impact on patients' global self-ratings of health. The negative correlation between the latent constructs of psychological factors and psychiatric symptoms is consistent with conceptualizations of symptoms of psychopathology as falling on a continuum of severity ( 14 , 22 ). The finding that psychological factors had a more significant effect than psychiatric symptoms sheds some light on the discrepant findings in past research.

Chung and colleagues ( 4 ) and Crews and colleagues ( 6 ) reported different outcomes from correlations between psychiatric symptoms and the reliability of self-reported health, even though each used the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) to assess psychiatric symptoms. One difference between the two studies was how persons with mental illness were identified. Mental illness was defined by scores on symptom measures in Chung and colleagues' study, whereas Crews and colleagues used formal diagnoses. It may be that Crew and colleagues had more individuals with serious mental illness in their sample. The mild end of the severity continuum is more likely to yield significant effects on self-reported health status among individuals with severe mental illness. The BPRS may be more sensitive to the psychological correlates of severe mental illness, even though they were not directly measured. The assessment of psychiatric symptoms in a patient sample that does not have severe mental illness may be more likely to miss these psychological correlates if they are not directly measured.

All of the observed variables representing psychological factors are associated with paranoid thinking in both clinical and nonclinical populations ( 14 , 15 , 23 , 24 , 25 ). The main observed variables reflected in the latent construct for psychological factors were self-esteem, distrust, and cultural mistrust. Self-esteem was positively related to self-reported health status, whereas distrust and cultural mistrust were negatively correlated. These psychological variables are particularly relevant to cultural paranoia in African-American populations ( 14 , 24 ). Ridley ( 24 ) asserted that cultural paranoia is protective against low self-esteem for African Americans. The facts that a lack of trust was associated with reports of poorer health and that high self-esteem resulted in better perceived health are consistent with this view. Thus the findings suggest that African-American psychiatric patients' self-reports of health status may be influenced by their level of trust in the health care provider and need to maintain a positive self-image. Cultural mistrust or cultural paranoia has been found to be associated with lack of trust in providers and with less satisfaction with health care among African-American patients in primary care settings ( 26 ). It should be noted, however, that only one of the four psychological factors had cultural relevance for African Americans. Given that the latent construct for psychological factors was primarily measured by more general variables, it is quite conceivable that a similar pattern of results would emerge for other racial and ethnic groups.

Contrary to the second hypothesis, the FBP scale and Fenigstein scale had the largest regression coefficients of all psychiatric symptoms in the measurement model. Objective assessments of psychiatric symptoms yielded weaker coefficients regardless of whether they were derived from standard intake assessments or research diagnostic interviews. Both of the subjective measures tap paranoid symptoms. The FBP assesses symptoms on the severe end of the paranoia continuum. The Fenigstein scale purportedly measures nonclinical paranoia, but past research on its use with schizophrenia patients indicated that the scale operates differently among chronic patients relative to nonclinical populations ( 27 ). The latent construct for psychiatric symptoms had less impact on the self-reported health status of these African-American psychiatric patients. This finding suggests that clinical paranoia was not as influential in these patients' verbal reports.

The fact that demographic variables did not have a significant influence on African-American psychiatric patients' self-reported health status in this study is noteworthy. This finding is at odds with findings of previous studies ( 1 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ). Demographic variables are often proxies for other social or contextual factors ( 8 ). It is important to note that my sample consisted of inpatients at the time of the study, so variations in social experiences that may occur for individuals as a function of demographic characteristics are likely to be minimized for chronic patients in inpatient settings. This assumption can be tested by replicating this study with a sample that includes both inpatients and outpatients with severe mental illness.

This study has a couple methodological limitations that should be considered in future research. The use of a sample of African-American psychiatric inpatients from one psychiatric hospital means that the findings may not be generalizable to the nonclinical African-American population, to chronic psychiatric patients from other racial and ethnic groups, or in different treatment settings. Also, self-reported health status was based on a continuous single-item scale. Future studies would benefit from the use of a multiple-item measure that has several subscales to serve as observed variables for the latent construct of self-reported health. Future studies with these methodological improvements will strengthen the argument that the self-reported health status of individuals with severe mental illness is similar to the general population's in terms of biased responses resulting from psychological factors.

Conclusions

The findings of this study have implications for the assessment of health status from global self-reports and the primary care of persons with severe mental illness. One barrier to medical care for physical illnesses of persons with chronic psychiatric conditions is the belief by physicians that their patients' verbal complaints stem from their mental illness ( 2 ). With the findings from this study, however, it can be argued that psychiatric symptoms are less likely to be a causal factor in self-reported health in this population. Psychological factors—namely, a lack of trust or cultural mistrust—associated with attitudes toward health care providers in the larger African-American community may also be found in the segment with severe mental illness ( 26 ). Along with others, I have advocated that clinicians directly address the trust issue in the provision of mental health services to African Americans ( 22 ). This recommendation may also be pertinent in the context of addressing general medical problems among African-American patients with severe mental illness. Finally, psychosocial assessments in health care settings should include a measure of self-esteem. Self-esteem data may help the provider determine whether reports of health status are accurate or represent an inflated self-image.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study is based on data collected for the Cultural Sensitivity Diagnostic Research Interview Project under the direction of Dr. Whaley, while he was a research scientist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The project was approved by the institutional review board of the institute, and it was supported by grant R01-MH55561-01A1 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Whaley. Dr. Whaley received training in structural equation modeling from Laura Klem, M.S., and colleagues at the Center for Statistical Consultation and Research, University of Michigan.

The author reports no competing interests.

1. Segal S, Gomory T, Silverman C: Health status of homeless and marginally housed users of mental health self-help agencies. Health and Social Work 23:45–52, 1998Google Scholar

2. Osborn DPJ: The poor physical health of people with mental illness. Western Journal of Medicine 175:329–332, 2001Google Scholar

3. Swartz M, Swanson J, Hannon M, et al: Regular sources of medical care among persons with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis C infection. Psychiatric Services 54:854–859, 2003Google Scholar

4. Chung S, Domino M, Jackson E, et al: Reliability of self-reported health service use: evidence from the Women With Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence study. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 35:265–278, 2008Google Scholar

5. Krause NM, Jay GM: What do global self-rated health items measure? Medical Care 32:930–942, 1994Google Scholar

6. Crews C, Vu K, Davidson A, et al: Podiatric problems are associated with worse health status in persons with severe mental illness. General Hospital Psychiatry 26:226–232, 2004Google Scholar

7. Washington O: Identification and characteristics of older homeless African American women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 26:117–136, 2005Google Scholar

8. Calhoun P, Wiley M, Dennis M, et al: Self-reported health and physician diagnosed illnesses in women with posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 22:122–130, 2009Google Scholar

9. McDonald RP, Ho MR: Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods 7:64–82, 2002Google Scholar

10. Whaley AL: Cultural mistrust and the clinical diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia in African American patients. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 23:93–100, 2001Google Scholar

11. Dohrenwend BP, Shrout P, Egri G, et al: Measures of nonspecific psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:1229–1236, 1980Google Scholar

12. Terrell F, Terrell SL: An inventory to measure cultural mistrust among blacks. Western Journal of Black Studies 5:180–184, 1981Google Scholar

13. Rosenberg M: Society and the Adolescent Self-Image, rev ed. Middletown, Conn, Wesleyan University Press, 1989Google Scholar

14. Whaley AL: Psychometric analysis of the Cultural Mistrust Inventory with a black psychiatric inpatient sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology 58:383–396, 2002Google Scholar

15. Fenigstein A, Vanable PA: Paranoia and self-consciousness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 62:129–138, 1992Google Scholar

16. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version, 2.0). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1996Google Scholar

17. Whaley AL: Symptom clusters and the diagnosis of affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia in African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association 94:313–319, 2002Google Scholar

18. Whaley AL, Hall BN: Cultural themes in the psychotic symptoms of African American psychiatric patients. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 40:75–80, 2009Google Scholar

19. Beauducci A, Wittman WW: Simulation study on fit indexes in CFA based on data with slightly distorted simple structure. Structural Equation Modeling 12:41–75, 2005Google Scholar

20. Jackson DL, Gillaspy JA Jr, Purc-Stephenson R: Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: an overview and some recommendations. Psychological Methods 14:6–23, 2009Google Scholar

21. Sivo SA, Fan X, Witta EL, et al: The search for "optimal" cutoff properties: fit index criteria in structural equation modeling. Journal of Experimental Education 74:267–288, 2006Google Scholar

22. Whaley AL: Cultural mistrust: an important psychological construct for diagnosis and treatment of African Americans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 32:555–562, 2001Google Scholar

23. Combs D, Penn D, Cassisi J, et al: Perceived racism as a predictor of paranoia among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology 32:87–104, 2006Google Scholar

24. Ridley CR: Clinical treatment of the nondisclosing black client: a therapeutic paradox. American Psychologist 39:1234–1244, 1984Google Scholar

25. Zigler E, Glick M: Is paranoid schizophrenia really camouflaged depression? American Psychologist 43:284–290, 1988Google Scholar

26. Benkert P, Peters R, Tate N, et al: Trust of nurse practitioners and physicians among African Americans with hypertension. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 20:273–280, 2008Google Scholar

27. Smari J, Stefansson S, Thorgilsson H: Paranoia, self-consciousness, and social cognition in schizophrenics. Cognitive Therapy and Research 18:387–399, 1994Google Scholar